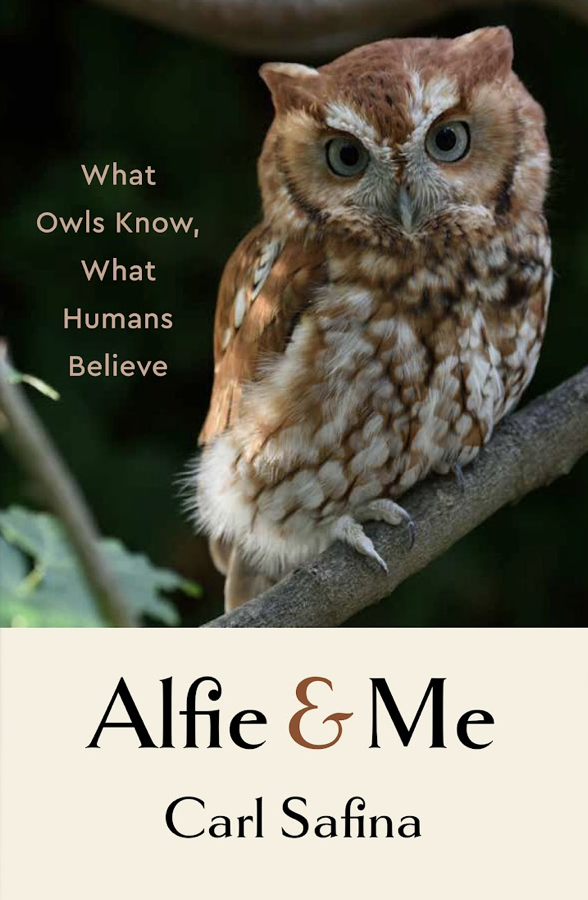

Alfie and Me: Owls Know, Humans Believe

Bioneers | Published: October 31, 2023 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

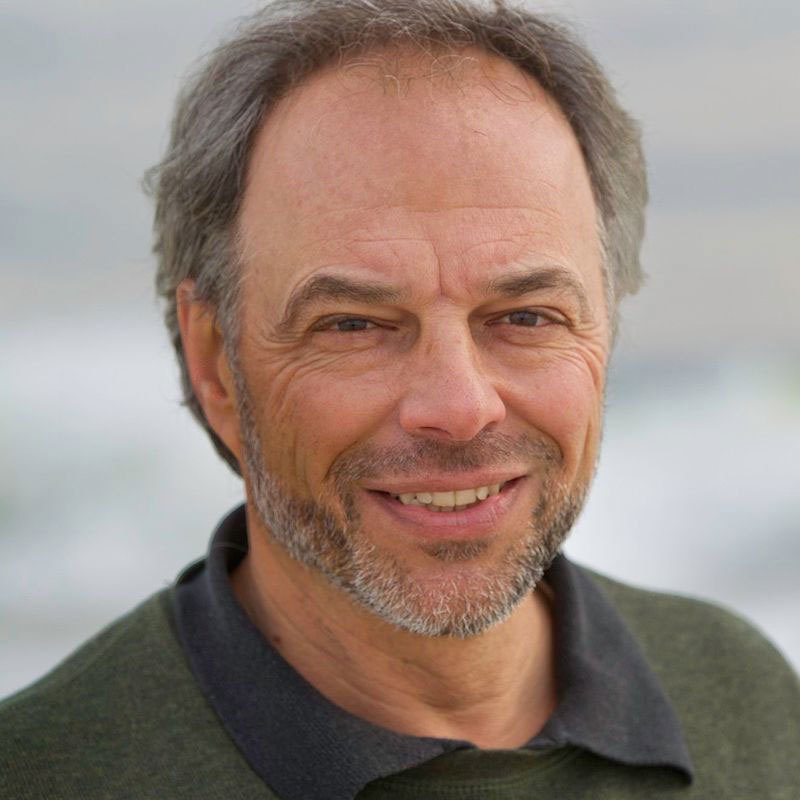

When the ecologist Carl Safina took in a wounded baby screech owl, he expected that she’d be a temporary guest, just like other wild orphans he and his wife Patricia had rescued over the years. But the tiny creature—named Alfie—took a long time to heal. Carl and Patricia could never have predicted that when Alfie was finally able to live free, she would choose to maintain a connection and establish her territory with their home at its center, attract a wild mate, and raise her babies right outside their studio window. Nor could they have guessed that the Covid-19 pandemic would grant the graciousness of time to form a profound bond with Alfie, while Alfie and her brood provided solace and sanity in a year upended.

The following is an excerpt from Alfie & Me: What Owls Know, What Humans Believe.

The little owl had for more than a year been living a comfortable, healthy life. A developmental setback stemming from her near-death infancy had delayed her departure. Now she was in perfect health, her new feathers soft and sleek and luminous with youth. She was a strong and excellent flyer who could execute tight turns and precision pounces. And she was perfectly at home in her roomy enclosure. But I knew—as she did not—the relative meaninglessness of a life without risks. An owl who is not out doing owly things is just a bird in a cage. But after this soft and secure salvation, could I really subject her to those meaningful risks? How “meaningful” would be injury, or starvation, or getting eaten? All this was on my mind that morning as she flew from the coop to me while I was offering her food. But it was she who made the decision. She merely touched my arm and flew across the yard, and suddenly was taking in the world from a new vantage point atop a tree. She hadn’t vanished. Not instantly. Not yet. She had been braided into our life. But now she was tugging back, pulling us into hers.

The Covid-19 pandemic that forced us to spend our year at home coincided with the unprecedented free-living presence of that tame little owl—rescued near death and raised among humans and dogs and chickens—who decided to stay around our backyard, got herself a wild mate, and became a mother who successfully raised three youngsters. Despite the pandemic and partly because of it, the year generated some good memories to ameliorate the not-so-good. The owl, the songbirds, and our pets gave us a daily off-ramp from the jammed-up highway of worries and dread. This is one story of profound beauties and magical timing harbored within a year upended.

Even in a “normal” year the perspective she offered would have felt like something new, a deeper perception of being. The little owl in this story is a living being in all the ordinary, extraordinary ways. But she is in no sense “just an owl.” Our deeply shared history as living things is why we had the mutual capacity to recognize each other, and share that strange binding called trust. She was my little friend.

Had the year proceeded as planned, my scheduled travels would have caused me to miss all the fine details of her life, courtship, mating, and their raising of youngsters. Had the year proceeded as it did—but without her—it would have been all the more grueling. She was literally a bright thing in our nights. She was a metaphor for sanity, at a time when sanity seemed increasingly at risk.

One can travel the world and go nowhere. One can be stuck at home and discover a new world. This was a year in which we stayed closer but saw farther. We came to see the many ways in which our daily existence is strange and romantic, unpredictable and quirky, buoyed and burdened with exotic customs as any place is. Home is always too close and yet too distant for us to fully know it. It can take a kind of magic spell to let us see the miracles in our everyday routines. Our enabling wizard was the little owl.

Something like a trillion and a half times, daylight has rolled across our planet of changes. About how we came to be, we are privileged to understand a few things. Devoted workers have lifted some sketches from layers of clay, from cells of the living, and from the lights of distant galaxies. No two days are the same, regardless of how small and petty and blurry we make them, how much we blunt our edge on imaginary surfaces that would be better avoided. Written in every rock and leaf and the lyrics of every birdsong are invitations. If we accept, and attend, we see that billion-year histories are the thrust that sends each blade of grass, that dreamscapes whirr within each traveling shadow.

My easy intimacy with an owl helped me understand what is possible when we soften our sense of contrast at the species boundary. My growing relationship with her made me want to better understand how people have viewed humanity’s relationship with nature throughout history. Why do we happen to have a strained relationship with the natural world? What are that relationship’s origins? Why didn’t we make a better deal with the world—and ourselves? How have other cultures throughout time and around the globe seen humanity’s place in the world?

Turns out, it’s complicated. Origins of values run deep. From antiquity, various peoples developed different realms of thought about the human being’s role in the world. I came to see four major traditional realms of beliefs and values: those of Indigenous, South Asian, East Asian, and European or “Western” traditions. The deep cultural past holds astounding power to clarify the sources of illumination and darkness that cast their light and shadows across the lives we live today.

A few years ago I traveled to Rome and to India. Italy’s magnificent sacred art varies mainly upon themes of people either writhing in agony as they are cast into eternal fire, or ascending to heavenly bliss. Little celebrates life itself. India’s ancient temples shocked me. The subject of their thousands of stone carvings includes abundant images of humans, sometimes with other animals, in various acts that would get you cast into eternal hellfire in Rome. Why, I wondered aloud, were holy temples covered with what the West would call pornography, or to put it nicely, freeform eroticism?

“Not erotic,” my mentor explained. “Sacred. Sex brings life. The West thought sex is dirty because they believe life is impure; your religious art worships only what is in heaven. To our religions and the artists of our temples, life is sacred. So what brings life is sacred.”

That brief, stunning, exchange not only exposed sharp contrasts but suddenly cast Western values in a lighter shade of pale.

Hindus perceived the creation, continuity, and decomposition of life; and assigned a corresponding divine trinity—Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva—who preside, respectively, over each of those major aspects of lived existence. Their Bhagavad Gita enshrines principles for human relationships with nature, the divine, and society. Meanwhile Christianity’s trinity, the “father, son, and holy ghost”—Christians say they’re three “persons” in one god—corresponds to little about Earthly life. The focus is resolutely on “Our father, who art in heaven,” not here with us.

The French Revolution rallied for “Liberty, equality, fraternity.” That’s a distinctly more pro-social trinity than the U.S.’s me-first, “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” The U.S. Constitution proclaims, “all men are created equal” but in practice, “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” is the starting gun of a rat race that confers domination to some and alienation to many.

Why not something more uplifting? I see another trinity. Beyond me, beyond us, beyond now. Imagine a nation predicated on pursuit of: community, compassion, understanding, commitment, environment, equality, creativity, beauty, service, health, nurture, nature, and what’s next. Trinities are catchy, so pick any three. Imagine this: having the enshrined right not to compete, but—to matter.

Alfie has had the chance to matter. Now five years old, still free-living and often seen in our backyard, she has raised three broods with her wild mate and sent ten young owls out into the world. Rescued near death, and despite the pressures humanity places on her kind, she has become a link in the great chain of being—with a little help from her friends. This little being able to see into darkness has helped put a little more light into my eyes.