Art, Science, Ecology and the Climate Crisis | An Interview with Joshua Harrison

Bioneers | Published: November 1, 2023 ArtEcological DesignRestoring Ecosystems Video

Joshua Harrison, a filmmaker, environmentalist and educator, is the heir to an illustrious legacy: his late parents, Newton and Helen Harrison, are widely considered to be among the most important and influential visionaries in the “Eco-Art” movement. Joshua, who has has been engaged in the intersection of art and ecology since participating in middle school demonstrations on the first Earth Day in 1970, became Director of The Center for the Study of the Force Majeure after the passing of his father in 2022.

The Harrisons worked for 40+ years with biologists, ecologists, architects, urban planners and other artists to initiate collaborative dialogues. Their concept of art embraced a breathtaking range of disciplines; they were historians, diplomats, ecologists, investigators, emissaries and art activists. Their work involved proposing solutions, public discussion, community involvement, and extensive mapping and documentation of their proposals in an art context. They did projects involving watershed restoration, urban renewal, agriculture, forestry, urban ecology, etc., and their visionary projects led on occasion to changes in governmental policy and to expanded dialogues around previously unexplored issues.

Joshua has continued in those footsteps and expanded the vision, as he pursues initiatives that bring together artists, scientists, engineers and planners to design regenerative systems and policies that address issues raised by global temperature rise at the enormous scale that they present. These projects include Living Forests, a multidisciplinary group working with the U.S. Forest Service, the State of California, artists, teachers, local communities, business and policy leaders to build a systems approach to the fire and water crises in California; as well as Sensorium for the World Ocean, a multi-sensory immersive installation that sets out to directly address the survival problems the world ocean faces as temperatures continue to rise.

Interviewed by Bioneers Senior Producer J.P. Harpignies. An edited transcript of the interview is below.

J.P. HARPIGNIES: The first thing I thought we should frame this conversation with would be to talk about your parents and their seminal role as preeminent eco-artists, for lack of a better term. And I think what is especially interesting is that their thinking and visioning, to use an awful verb form, was on such a large scale—I think maybe on a larger scale than any other folks working in what would be called the eco arts landscape—and also the fact that their work could be a bit confusing re: what component was art and what was science, and if there even was such a boundary, and they were certainly exploring that boundary. So just for a few minutes, if you could frame a little bit of that, then we can get into your work.

JOSHUA HARRISON: Sure. In fact, everything we do at the Center evolved out of their groundbreaking work, and I think their work really evolved over time, but I think where it ended is a good place to begin.

They early on realized that looking at problems brought them into the context of other problems, and that no matter where they went, they had to look larger and more globally, and they ended up in a position that they needed to look at the environment as a whole in order to be able to address every element of it within.

And a little bit of background…As artists, they came to this with an odd mixture of classical training. My father was first a classical sculpture, then an abstract expressionist painter, and then was fortunate enough to be drafted by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver as one of non-scientist artists chosen to work with scientists for nine evenings of art and technology, which later evolved into some of the seminal technological work my father did.

And then when my mother started working with him, they started to move into ecological work. My mother came from literature and history and teaching. They started in a dialectical mode that never left, and that dialectical sense of education and interest in research versus vision and perspective, and profoundly questioning the world which we’re surrounded by, formed an intense curiosity, combined on each of their sides, about what was going on, which led them down innumerable pathways and eventually got them to the point that they needed to understand ecology, so they talked to themselves about ecology. They needed to understand systems, so they talked to themselves about systems. They needed to understand collaboration in a sense. They had the initial collaboration among themselves, but then they realized that all of this work was larger than themselves.

So, it became this quest, and all of their observations would show them that things were badly out of balance. There were tremendous misapprehensions in the way people dealt with the world over the last several thousands of years, especially the 500, 600 years of “Western” civilization. In particular, we’d ended up putting ourselves in a place where instead of being in a reciprocal relationship with the world around us, instead of being able to be part of an ecological pattern like the rest of the species on the planet, we went into this sort of complex imbalance.

And so their work was an exploration into how to stop taking and start giving back, at least as much, if not more, to the life-web as we take out. They were fortunate enough to be at UC San Diego at a time when it was a really an intellectually active place – the politics, and science, and oceanography, all the expertise one might imagine, across the landscape, and it was not only available, it was accessible.

The art world in the ‘70s was also very similar in many ways to the film world at the time. It was open. It had lost a certain amount of academicism, and all of the strictures that had said there’s painting, there’s sculpture broke down. There was conceptual art. Conceptual art stopped needing to have a physical object that had to be placed in a gallery. An art process could be an idea, an understanding.

And then they started working with living creatures to see if that could help them broaden their understanding, and that process brought them into a larger dynamic, into experiments in art and technology. The first work Helen contributed pretty radically to was the brine shrimp piece, which was really an aesthetic piece. Brine shrimp are different colors at different stages of their life-cycle, so they wondered what would happen if you basically took brine shrimp in a series of ponds and fed them at different times. What would the colors of those ponds be? It started as a largely aesthetic piece, but it became an understanding that this was actually life that was doing this, and that led them into growing more and more things in a series they called survival pieces.

In the early ‘70s, they were growing plants and weeds and raising bees, generating ways that people could actually get back into direct contact with the natural processes of life. They made soil. They did all kinds of things. And because they were artists, they showed them in art spaces. That had certain advantages and certain kinds of complexities. Did they consider it art? How do you consider art? Where are the boundaries?

In the early 1970s, they had a show at an art museum called Duck and Snail. Snails are an invasive species in California brought in by priests in the 1840s and ‘50s because they wanted to have escargot, some of whom of course escaped (slowly…) and became a major invasive species. The goal of the show was the discovery that ducks eat snails, and so you could have a show with a garden with snails and a duck eating the snails.

One of my favorite reviews of that was in the local paper; it said: “If this is art, give me broccoli.” But their goal, as conceptual artists, was to provoke a conversation; they wanted to make people think, so asking if it was really art was a question that didn’t bother them. In fact, they invited people to query what was going on with their work, with life.

Earlier on, in 1971 as part of LACMA’s landmark Art + Technology exhibition, there was a conversation with some of the scientists at a jet propulsion laboratory who asked whether or not the plasma discharge that my father was working with at the time could be used to create an artificial aurora borealis over the mid-latitudes of Los Angeles. And NASA was extremely interested. They actually procured the services of a Nike-Apache missile for a payload; they drew up a plan; they got the Vandenberg Air Force Base to agree to launch the missile, and the last thing they needed was the approval of the Secretary of Defense, a guy named Melvin Laird, during the Nixon administration, but it got rejected.

The next year, they tried again, because they were still interested. This is an idea today we would never do because it’s risky geoengineering at a massive scale, but at the time people hadn’t reached that level of consciousness, so it went back through the same food chain—Vandenberg agrees again; the missile is still available; the payloads are set up; the delivery systems are ready; NASA’s ready, but Melvin Laird sent back a telegram that said: “I’m not going to let any damn artist fire a missile off from one of my bases. “Is that art? Is that science? Is it provocation? I think that was one of the things that they both enjoyed about the work they did—if it could inspire positive reactions or it could challenge people’s basic understanding. They loved that.

They had a concept they liked to use called Conversational Drift, where you set up some tension in a museum or art setting, because those settings take you out of normal discourse. If you’re trying to present a scientific paper, then your subjected to a set of strictures of science. You have to be cited in a particular way; you have to have peer-review. If you speak at a news conference, you have another set of rules, but if you’re in a gallery, you’re sort of in a protected space, and if you’re an artist making scientific conversation of different kinds, you’re also in a sort of protected space, and that allows you to get much more vocal and ambitious than in other conditions, so they very much liked to use gallery and museum spaces as jumping-off points for letting people think about stuff differently.

And they liked to use the tools and metaphors of art—perspective, figuring ground, how to look at things as an outsider, etc., and apply those to the conditions of the landscape of the world. That gave them an opportunity to create discussions from a tiny to an enormous scale about how we should think, and they were never more pleased than when the conversation left the gallery space and moved into the public arena in different ways.

The greatest example of that was when they were invited to the Netherlands to help solve what was essentially a housing crisis. The most populated province in the country was also the province that had the most park and farm land, and the Dutch were trying to figure out how to build 300,000 more houses. They’d come to a two-year standstill, and one of the local art museums said: “Let’s invite these two crazy American artists and see if they can help us.”

One of the ways that you can do this sort of work is to come in as an outsider with a fresh perspective, but you can’t be a useful outsider without knowing what the local people are doing on the inside, so in their process, they connected with a team of local experts and students, and they spent a week or two sort of trying to see what was going on. And they came out to a public presentation where they turned all the planning and maps upside down, drawing a big red X on everything. The problem, they said, is you’re doing this totally wrong: you’re trying to pave over this parkland when really what you should be doing is infill around the existing towns and cities, and building green space. In retrospect, not a complicated idea, but it had escaped the understanding of the local people who had become so locked into their battles over the planning apparatus.

That turned into 50 or 60 public meetings and ultimately a larger, detailed plan, but then the government changed in Holland, and it got dropped. Five years later, the government came back and the plan was adopted. They weren’t necessarily credited for it, but that’s what happened on the ground, and that’s the kind of conversation drift that they really appreciated.

JP: Again, though, the issue comes up that that’s great, but in a way it’s hard to differentiate it from a really innovative approach to urban planning.

JOSHUA: I think it’s a fair critique, but it misses one of the things that they did that maybe I’m not articulating as well as I could. They tried to bring all elements together. Their great insight was that systemic problems require systemic solutions, and they did that by asking the sort of naïve questions that you don’t often get to ask when you’re in a professional setting, but then they added expertise to the mix.

Maybe another example is one of their early experiences that brought them into the world of the oceans and that eventually became The Lagoon Cycle, in which they transferred a depleting species (the mangrove crab Scylla serrata) from the lagoons of Sri Lanka to a lab at UC San Diego and then to the Salton Sea. They had been growing plants, and they had a friend who suggested that they try to grow animals, and there was a particularly hearty lagoon crab in Sri Lanka that he suggested might be a good place to start. And they got these crabs, and they asked themselves: “What would make a crab happy?” On the notion that a happy crab would want to reproduce. And then they asked a second question that in retrospect is dead obvious, but nobody had ever asked it before, which was: “When do crabs reproduce?” Well, they reproduce in the monsoon season. And then the third question that led from that is: “What would happen if we created an artificial monsoon in a laboratory setting?” They ended up being the first in the history of science to figure out how to raise crabs in captivity.

They then were faced with the problem that the crabs would eat each other. They started to look at crab dominance behavior, and they found ways to separate the nesting sites far enough away from each other to reduce the dominance behavior so the crabs could actually reproduce and grow. With those two acts, they actually created the opportunity for an entire field of aquaculture and stunned the local scientists at Scripps Institute, that these two crazy artists had figured this out. In retrospect, it’s not a hard problem, because like many scientific innovations, it looks simple in the rearview mirror, but it hadn’t been asked or done before.

JP: That’s fantastic and impressive, but it still strikes me, just looking at it from the outside, without the context of their entire body of work, as another example in which you could say: “Wow, they were really good scientists, because it’s a pure scientific experiment.”

JOSHUA: It’s a cultural experiment too.

JP: It’s an aquacultural experiment.

JOSHUA: It’s a farming, it’s a food. It touches on a lot of different things. But you’re right. They did some things that were science. They did some things that were social planning. They did some things that were environmental engineering. In a certain sense, the ‘70s conceptual world allowed you to say you can do whatever you want and if you put it in a gallery, then it’s art.

JP: Which is why there was a lot of resistance to it, as well. I’d like to cover two things: How did their and your thinking evolve to get into the whole Force Majeure concept? Also, for you personally, what was it like to take on the mantle of this legacy, and was that something that you had resistance to or embraced from the get go?

JOSHUA: That’s a good question, and that ties into all kinds of issues. On the one hand, I had this really remarkable childhood. I grew up in the middle of this intellectual and cultural ferment—in Europe and the United States, people coming through the university, so the idea of the work, the idea of my parents exploring these big ideas and processes was part of the oxygen of my childhood and my life.

One of my early post-college experiences was that they asked me to participate in a collaborative venture at a place called Artpark in Lewiston, New York, in the late 1970s, wherein we electively created a community effort to convert a 60-acre landfill into land clean enough that you could at least picnic on it. That was a pretty powerful and effective experience.

But after that, I had my own career and went on and did a number of other things over the course of my life, and then as my parents got older, they basically asked me to rejoin them and to sort of help them in their last years, so it’s a truly complex task for me to both be a son and someone who respects and admires the value of their legacy, and also to figure out how to carry that on, because I am not them. They are who they are. They were in many ways larger-than-life figures; they moved in a universe that allowed that to happen. They had a lot of lucky breaks fall upon them that allowed them access to such figures as the Dalai Lama and all kinds of different individuals and places.

At the same time, the motivating work of their life, which I’ve sort of alluded to, is how to give back more to the world than you take. How to help design and rebuild systems that can do that is something that I massively identify with, so as we developed the center, the goal is to help resolve this innate contradiction in modern life, which is that we, as humans, are part of the world but stand apart from it, largely due to the protections of cheap fossil fuel energy and the attitudes around extractive behaviors all across the board. How do we break that down?

JP: In general, I’d say it’s our extensive use of technology that sets us apart.

JOSHUA: I would tweak that a little bit in saying yes, but it’s the fact that we’ve been able to take stored power to let us take this kind of technology, and that we haven’t taken into account that that’s a one-way system. Technology is perfectly capable of existing inside of a different world order, and we have a perfect example of it—Indigenous technology; traditional technological science and insights, which were massively suppressed but we’re now starting to look at much more closely and understand that 10,000 years of close observation of the landscape distributed by oral history informed by culture has its own ability to answer questions in a very analogous way. In fact, that’s some of the work we’re doing right now, to technology.

JP: They also had the advantage in terms of the ecosystem of only using biodegradable materials, because that’s all that was available to them.

JOSHUA: Exactly, but we will need to understand that if we take the planet, if we take the Gaia Hypothesis seriously, that the Earth is a self-regulating whole system, we have to function within the energy boundaries of that system, which is to say that every output has to be an input for something else. We can build complex polymers and molecules that also breakdown into simpler tools. That’s only hard to do if we exclude externalities in our conversation, but once we start including what Economics traditionally did a lot to exclude, then those conversations become very different, and technology solves problems differently and becomes the tool in a different universe, a universe in which we don’t use as much concrete, for example; where we create sponges, not barriers. It’s still technology; we still need to understand all kinds of things like water hydrology, but we’re just using it in a way where we build back reciprocating systems.

JP: So, Josh, let’s explore now how both your parents’ thinking evolved throughout their lives, and how they wound up with this really enormous vision, this global vision, in a lot of their projects, and how they got to the force majeure concept, which is a bit of a strange one, because in legal terms, a force majeure is often used as an “act of God,” something that you can’t insure against.

JOSHUA: That’s precisely why they chose it. They chose “force majeure” because it refers to a legal term where things are beyond your control. They referred to the collapse of global systems due to the widespread use of industrial technology—the overload of carbon, the depletion of our food cycle, etc., etc.—that has outcomes that we can’t control.

They actually created the institute they called The Study of the Force Majeure to look at these large systems caused by extractive industry and bad understandings of carbon loading, and all these other industrial civilizational choices we’d made that create these unexpected outcomes, like, for example, the global fire crisis right now. Utterly predictable, but we still got ourselves into it, and now it’s here, and in the last five to ten years, it’s gone from something that people looked at locally to something that people understand is a global challenge and process. And that’s a force majeure issue, because it relates to outcomes that had been generated by the fact that we haven’t paid attention to all of the grounding principles.

My high school newspaper had a motto: When you’re up to your ass in alligators, try to remember that your original intention was to drain the swamp. And that’s kind of where we’ve gotten into in a number of different places, and that’s where force majeure came from.

To get back to your question about scale, I think that act of growing the crab was one way that led them to building something and looking at crabs as aquaculture. Then that led them to an aquaculture that actually becomes a system of food production that’s more sustainable in a sense, that’s more ecologically available that other kinds of extractive industry, certainly in California. And they started looking at the Salton Sea, and they went back to Sri Lanka and understood the thousands of pre-industrial uses of water and water conservation and tunnels and things that were going on.

While they were there, they had this remarkable insight. They started watching a farmer with a water buffalo and another farmer with a tractor, which became one of their iconic images, of a farmer in Sri Lanka. And they started to do the ecological arithmetic and realized that when you added in fuel of capital cost and expenses of the tractor and output, and you counted the ecological impact—food, fuel and output—of a farmer with a water buffalo, the water buffalo and the farmer came out on top.

That led them to sort of exploring that more fully and to the lagoon work; it led them to look at essentially aquaculture on a massive scale. That led them to looking at the “ring of fire” around the entire Pacific Rim, and then that led them eventually to look at ocean systems.

From looking at how a crab grew or how you could grow a crab in captivity, that led them to looking at increasingly larger life systems, and that particular pathway is charted in the work they called The Lagoon Cycle, which will actually be on display in San Diego as part of the Getty Pacific Standard Time starting in September, as well as a retrospective of much of their other California work across four different institutions in San Diego.

JP: In September of ’24?

JOSHUA: September of ’24. Getty runs a quadrennial series called Pacific Standard Time, and this year it’s on “Art and Ecology.” Four of the institutions participating are highlighting historical works by Newton and Helen. The fifth one is the Sensorium, which is Newton’s last work, which we’re continuing on in his absence.

JP: Could you explain what the Sensorium is?

JOSHUA: Sensorium came out of a really simple question that Newton came up with, which is: Is there a way you could ask the ocean a question? And if you were to ask the ocean a question, how would it answer? We’ve been talking about natural systems and now we’re going to talk about our technology as we more commonly understand it.

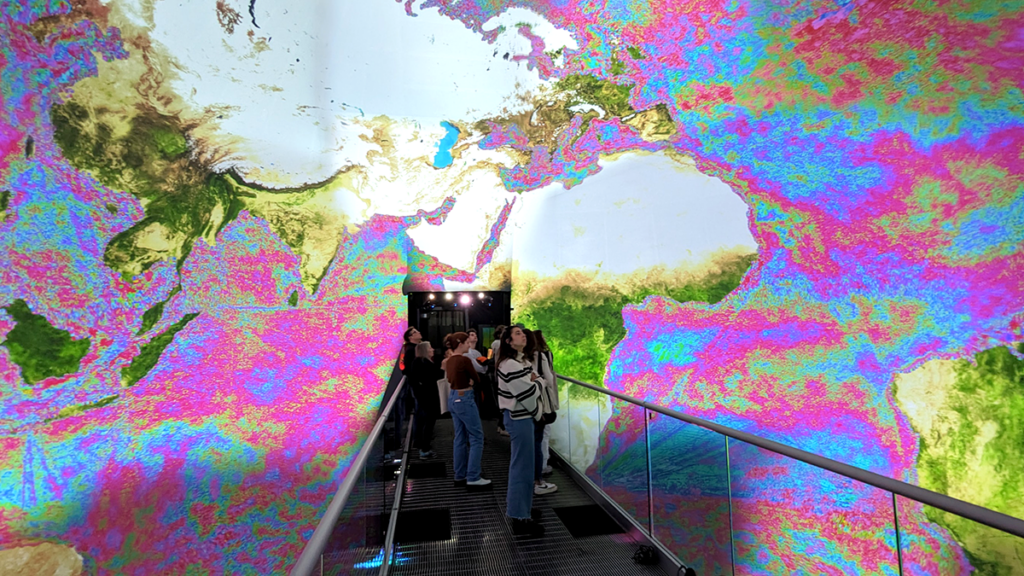

The understanding and analysis of ocean systems and the ability of technological modeling had reached a point where you could probably create a system that could match many of the complex systems that are in the ocean, and if you could find a way to visualize that interrelation and take it out of a computer screen and into three-dimensional space, so that you could really create this transcendent experience that could on one hand be absolutely compelling emotionally, visually, personally, but also allow you to really see and visualize, from a different perspective, how these systems interact. That was the insight that drove Sensorium, and we built a tool that allowed all these systems, and many of the ocean systems that we understand, and the modeling that we understand, and the real-time data that we understand, and we put these all together in a space where we can actually see it.

JP: Are you talking about data like temperature, salinity…?

JOSHUA: Temperature, salinity, acidity, coral reef growth, fishery depletion, atmospheric carbon, water carbon, currents, as many different parameters as you can bring data in.

JP: Is no one else doing this in terms of scientists working on it?

JOSHUA: I think it’s a really good question. I think historically science has been focused on individual connected systems. There’s a lot of smart scientists out there who are starting to see the necessity to connect other systems.

But this is kind of a generous piece, to try and build something that shows everything together, and it’s not a pure science. It’s a piece that’s a hybrid of the desire to visualize and see, and engage with the experience as well as tools to adapt and look at it.

JP: In a sense, that’s a clearer artistic component than some of the other of their projects, because there’s this really desire to have an emotional impact on the individual who engages with the Sensorium, right?

JOSHUA: I think so. Although, if you go into some of their other pieces, they were capable of extraordinary vision and beauty, and have had, on an individual level, quite a profound effect. This is a more intentional version of that.

JP: I mean, I’m just saying in their earlier pieces, some were clearly what old-school people would understand as art, some to be more pure science, and this is almost a return to the synthesis of art and science in a very understandable way, it seems to me.

JOSHUA: I think so. I think, in alignment with the Force Majeure Center, Newton was hoping to move away from a position where the art in the world was too abstract for people. The goal of Sensorium is to take really, really massively complex modeling sets and overlap them, but also create a space you’re really in the middle of, so that it’s not abstract, not far away, and that allows you to sort of get into this liminal sense.

The goal of all of our work, Helen and Newton’s work—after Helen died, his work, and now my work—is to open up the conversation so that we shift our perspective and consciousness about how we look at the world around us, what’s important. Because until we do that, until we understand that the value of life is different than what we have sometimes done with it in the last several hundred years, we aren’t going to do the things that are valuable. We aren’t going to reformat our lives more ecologically if we don’t think it’s a valuable thing to do. If we don’t see the relationship between ourselves and nature, and see ourselves it’s going to be a lot harder for us to think about, understand, engage, and deal with the process.

This piece behind me is a piece of work on the commons of Scotland, and one of those commons is the intellectual commons, the commons of mind. This is never clearer than when you look at Indigenous epistemologies and hierarchies about what’s important, and you look at what the boundaries of what we call technology are and what the boundaries of Indigenous technology are. Among many differentiating factors, the most important one, in my mind, is that with Indigenous technology, the culture is vital in making art; it’s in what you look at, how you understand it, and what you do. Whereas, contemporary technology is deliberately agnostic to matters of ethics, matters of culture, matters of morals. That’s the space we’re working in—How do we bring back the ethics, the morals, the culture, the decisions? And the way to do that, from the perspective of the Force Majeure from Newton and Helen’s work, is to bring up the challenges of how important this is, how this can all work, and how the systems work, and the value of it.

If we can do that, then people come out of it and say: What can we do? How can we work? And then they can start looking at and approaching the landscape of the universe that we live in somewhat differently.

JP: It seems to me that it’s really important for this to work that you reach enough people so that it has an impact. And then my question is: It seems to me that somewhere such as the Getty (and this is the same risk we run into at Bioneers), one is just preaching to the converted; the type of people who’ll be attracted to experiencing it are already people who have been already reading books about green philosophy…

JOSHUA: I think that’s always true, but it’s also where you start and then where you go. With something like Sensorium, the Getty is the vehicle to start it. Over time, as it develops, the goal is to turn it into a digital tool that can be accessible anywhere, without boundaries. And we’re not looking at gatekeeping.

The work we’re doing in collaboration with the AlloSphere at UC Santa Barbara, which has allowed us to do a lot of this visualization moved away from a wish to a reality because they have the means and technique to actually create these data visualizations to the level of sophistication where they can actually be used in scientific experimentation.

Our technical partners in this are in a group called the NanoSystems Institute of the University of California at Santa Barbara. The Director of that, JoAnn Kuchera-Morin, has built this sort of three-dimensional space, this ovaloid space that actually projects detailed data in real time space. They’ve started working with material science and at the molecular level where you can move atoms and molecules around until you can see what you would normally need an electron microscope to see. It took a lot of sophisticated hardware to do and actually be applied in a virtual space with a level of accuracy that it can actually be used for real-world experimentation.

We met JoAnn and realized that this was a tool that could actually take the vision of Sensorium out of creative imagination and actually make it real. So that then becomes sort of the technical background for this.

JP: So, they sort of had the template and technology to create the kind of three-dimensional space you were looking for?

JOSHUA: Right. And then once we can do that, then all ecological systems have similar components and we can use it for forestland, for drainage, systems; you can use it for atmospheric questions, anywhere where you have those kinds of interactive, complex, interlocking datasets. They can work at the affinity and scale and detail of the data, so the better the data, the stronger the work comes out. They became our technical partner. We had actually looked at a bunch of different technologies, and they were by far the most creative.

But your question was about community, and I think one of the things that I would say is that it’s kind of preaching to the choir, but as we’ve moved into a world where people understand increasingly that climate is a really big issue, our other observation is that there’s a lot of frustration, partly because of the doom and gloom, partly because they don’t know what to do.

I think of it as, to some degree, brought on by An Inconvenient Truth, which to my mind used this incredible moment to talk about climate and carbon, and created this really emotional experience, and then put people in a dead end. The last scene was a massive strain of 100,000 of many, many things but running so fast that no one could grasp anything, so it left a lot of people, myself included, feeling like: Wait a second, what just happened here? I want to do something about this, but I feel I can’t now. Al Gore had a group of people that he trained and that was his strategy for moving forward, but I don’t think it’s sufficient to the scale of the problem.

But what it did leave me to understand, and this is another piece of Sensorium, is that you can’t just have this liminal experience. You have to create a place that’s not a dead end, so with Sensorium, we’re also connecting to something called the Resiliency Map. Once you leave the experience, you’re also given an opportunity to sort of look at a global picture of hundreds if not thousands of different people doing, through different groups and organizations, similar work, and potentially ways to connect to any of them that you’re interested in. And its fully articulated version will be some kind of a tool that you can ask what you’re interested in, and finding different groups doing those things. If you just want to do a beach clean-up, here you are. If you want to get deeply involved in policy, these groups do that, so it gives people an opportunity to engage with their feelings of what can I do.

We’re in a difficult situation, but it’s not over and there’s plenty to do. And there’s also, I think, a great deal of ignorance about how much is being done. Bioneers is a wonderful example of all these different things that people are doing, but I think oftentimes people feel stymied because they don’t realize just how much work is happening, and how much is going on, and how much other activity there is.

Another thing—and this is the fault of the scientists—is that most of our models of resiliency underestimate how quickly natural systems rebound, so we’re unnecessarily skeptical and depressed about how hopeless we are.

JP: Well, it’s a double-edge sword though, because, as you know, the forces of the status quo and the oil and gas industry will jump on any opening you create, so if you tell them that nature’s so resilient, they’ll say, great, we can just keep pumping stuff into the atmosphere. That’s the fear.

JOSHUA: You’re right. I don’t think it’s something where you can sit there and say we don’t have to do anything because it’s so great; it’s that there’s a huge amount of hopelessness. The multi-pronged attack the oil and gas industry does includes this very inverse sort of man’s hierarchy of needs—hierarchy of greeds, you might call it—where you get to the point that you have to acknowledge it’s a problem, but then you tell people, “Yeah, it’s a problem, but there’s nothing you can do about it. It’s too bad; it’s too big, so since there’s nothing you can do about it, you might as well let us go to the commons and eat, drink and be merry until there’s nothing left and we’re done, and goodbye.” So that’s sort of a counter argument to that process. And it doesn’t have to be public, it’s just sort of implicit in the conversation. The examples that you show are that if you get involved in something, you can actually see a result. That’s really the core here. If you do something and you’re involved with the right kind of people, in real time, you can see, in a matter of years, not a millennium, you can see real results. That’s the piece that’s useful to keep in mind.

I’m drawn to Gramsci’s famous quote: “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” And we’re in the time of monsters, but Sensorium is an effort to look at being in the time of monsters and helping people see that there is a new world, and the people can ideally become part of it. It doesn’t have to convince the unconvinced. It’s not about that.

JP: You want to give the choir the chance to be more engaged and feel less hopeless. It seems to me that an ideal target audience for this sort of thing would actually be scientists, because, as you were saying, scientists have a tendency to be in their silos and to be somewhat reductionistic, so to give them a more holistic sense of how all these different disciplines connect has great value. They may actually be a group that could benefit most from being exposed to this.

JOSHUA: I think you’re right. And we’ve had very good experiences with scientists, a little bit self-selected. Newton had a really good experience with that too. It’s all about finding the right cohort. It’s not just scientists, writ large. All you need to do is find a few people who make sense, and then it moves from there. The scientific community is definitely one that we are interested in connecting with on this.

JP: Great. We’re running short on time. Is there anything you’d like to say in closing that you really want to impart that you think is fundamentally important about the work you’re doing?

JOSHUA: I guess first I’d like to say, we’ve talked a lot about Sensorium, but we work in three areas. We work in Sensorium as the ocean piece. We also work in forest and landscape, and we do a lot of work bringing a different balance to how we deal with fire and water on the landscape, and that involves these wonderful collaborations between tribal groups and the Geospatial Analytics Lab at USF and other sorts of very technical groups looking at fire prediction and spread, and looking at traditional history and bringing that into the notion that you have to talk to young people, and you have to reconnect young people. If we can work with tribal kids, at-risk tribal kids, and bring them back into the system, what we learned there is replicable and needs to be shared in all kinds of other areas. So that’s one of the groups that’s been going on, and it started from a very technical set of reports that we were invited into by the US Forest Service to look at a 10,000-acre landscape analysis of the Central Sierra and Western Nevada. It included work on creating fire simulations and understanding what happens under different kinds of landscape treatments, and bringing agency back to people who are connected to the land.

The other branch of work that we do are what we call “future gardens” that try to take a sort of very discreet place and look at future casts back 50 years and sort of say, based on what we think we know by looking at historical terms, looking at paleobotany, by looking at what we know about prediction, what will this land look like in 50 years. And we bring that in today and get people closer to the experience of what the future will be, and maybe learn from that, so we have a series of those gardens, including one at the UC Santa Cruz Arboretum.

JP: And you’re talking about the future in terms of climate change and so on, how the land will change as a result of climate change?

JOSHUA: Right. Most of what we do sort of comes from these guiding metaphors. The metaphor of a future garden is: Every place is a story of its own becoming. That is, every place has been warmer, hotter, wetter and drier than is now. By understanding the past and by understanding our best guesses of the future, we can start to look at what is likely to happen in an area locally, also in particular communities. If you’re looking at a 50-year time investment, you have to tie it to an institution that has a time horizon that’s very substantial and interested in natural processes, so we have botanical gardens and art communities, forests and universities. We have a number of different places where these are anchored into the experience. So those are the sort of three interlocking areas that we look at.

JP: So, you’re sort of working on the macro and micro level because you’re working with specific ecosystems and discreet gardens and landscapes, and you’re working with this giant conceptual work with the entire ocean.

JOSHUA: Absolutely. We’re sort of working from the macro to the micro. And in the forest work, we’re sort of working in the middle, going back to the macro and to the micro.

JP: So, the micro, the mezzo, and the macro.

JOSHUA: Right. They’re all related. They all talk to each other, so we need to do our best to sort of enact them. Again, our goal is to help, in the levels that we can, create new conversations, new opportunities, and new ways to bring people back into a different vision of the world in which they live.