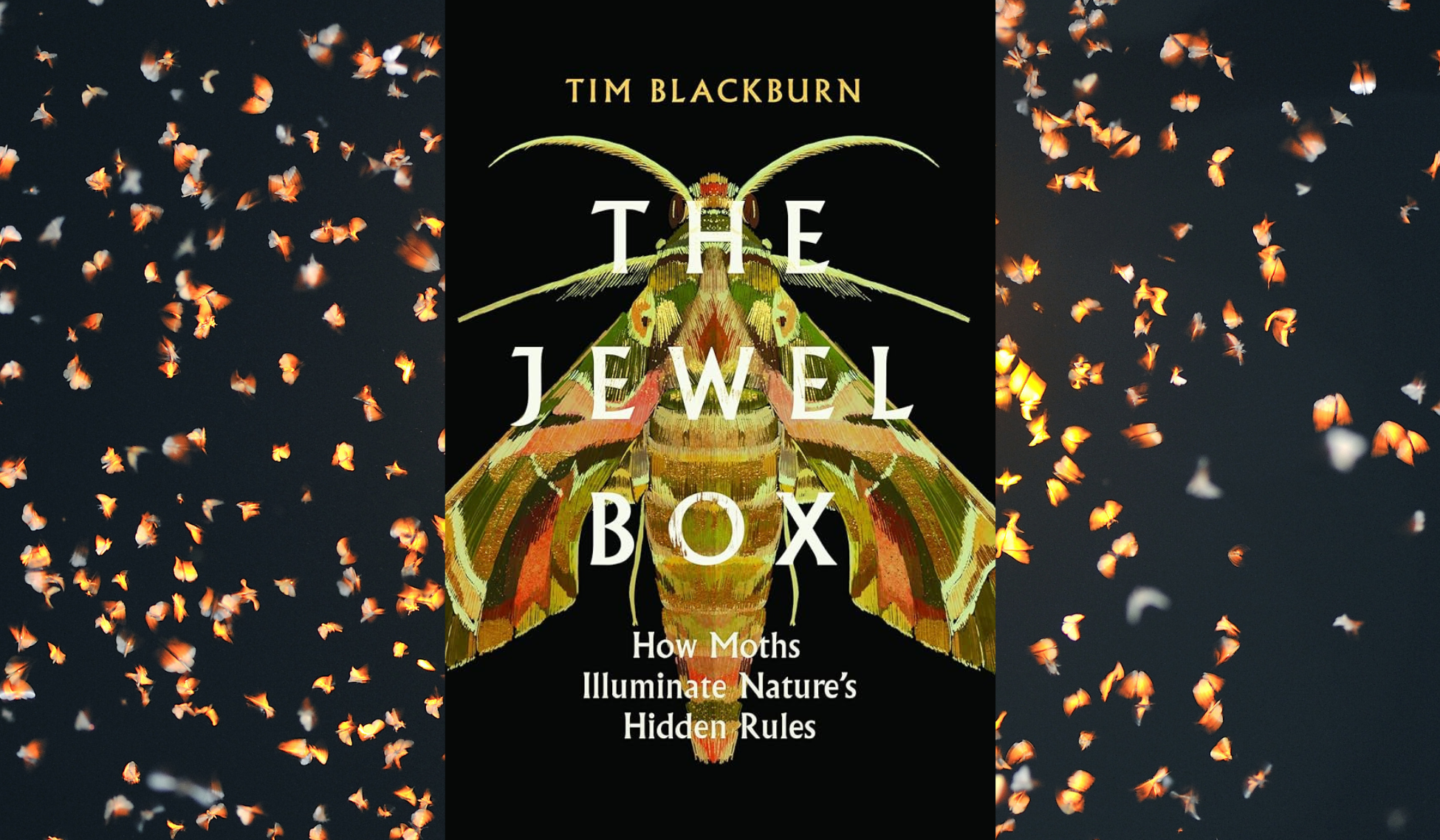

The Jewel Box: How Moths Illuminate Nature’s Hidden Rules

Bioneers | Published: July 3, 2024 Environmental EducationNature, Culture and Spirit Article

A plastic box with a lightbulb attached may seem like an odd birthday present. But for ecologist Tim Blackburn, a moth trap is a captivating window into the world beyond the roof terrace of his London flat. Whether gaudy or drab, rare or common, each moth ensnared by the trap is a treasure with a story to tell. In “The Jewel Box: How Moths Illuminate Nature’s Hidden Rules,” Blackburn introduces these mysterious visitors, revealing how the moths he catches reflect hidden patterns governing the world around us.

With names like the Dingy Footman, Jersey Tiger, Pale Mottled Willow, and Uncertain, and at least 140,000 identified species, moths are fascinating in their own right. But no moth is an island — they are vital links in the web of life. Through the lives of these overlooked insects, Blackburn introduces a landscape of unseen ecological connections. The flapping of a moth’s wing may not cause a hurricane, but it is closely tied to the wider world, from the park down the street to climatic shifts across the globe. “The Jewel Box” shows us how the contents of one small box can illuminate the workings of all nature.

About the author: Tim Blackburn is a Professor of Invasion Biology at University College London. Previously, he was the Director of the Institute of Zoology, the research arm of the Zoological Society of London, where he still has a research affiliation. He has been awarded Honorary Professorships at the Universities of Adelaide, Birmingham and Oxford, been named an Honorary Research Associate at the Centre of Excellence in Invasion Biology, Stellenbosch, and been an invited plenary speaker at numerous international conferences. His work in the 1990s with Kevin Gaston helped to define the newly emerging field of macroecology — the study of large-scale patterns in the distribution and abundance of species.

The following is an excerpt from “The Jewel Box” by Tim Blackburn.

Chapter 6

The Silver Y: The Importance of Migrants

Come my friends, ’tis not too late to seek a newer world! . . .

To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield!

— Alfred Tennyson

July 10, 2016. After almost two years of competition between the nations of Europe, France and Portugal faced off in the final of the UEFA European Football Championship, broadcast live from the Stade de France in Paris. It would be a memorable game. Not for the quality of the soccer—it took extra time and 109 minutes for Portugal to upset the hosts and score the game’s solitary goal—but for a most unusual pitch invasion. The stadium was descended upon by hordes of moths.

This was not a few stray insects, but a true swarm. Moths were everywhere. They clung to the goalposts and nets. They dotted the corner flags. They fluttered over the players and officials. Portugal’s star striker, Cristiano Ronaldo—one of the greats of the modern game and expected to be a major influence on the outcome of the match—had to be stretchered off injured in the twenty-fifth minute. As he waited, distraught, for the medical staff to come on and treat him, one of the moths landed on his eyebrow, as if to drink his tears (some moths do do this; within minutes this one had its own Twitter account). Moths are not partisan, though, and the French players were equally bothered. Media reports from the game discussed the insects almost as much as the football. It gave an insight into what it must have been like in Medford in the 1880s when [Spongy] Moths were consuming the town.

Photographs and video from the Stade de France show that the great majority of the pitch invaders that warm July night belonged to a single species: Silver Y. These are remarkable moths.

Fresh adult Silver Ys are a subtle blend of pink and brown, but most of the ones I catch in London are a careworn gray. Even worn specimens retain the distinctive silver letter on their forewing, from which the species gets its English and scientific names. Worn specimens also keep their striking profile—a heavy fur collar sweeping up into a punkish tuft of scales on the thorax, dropping down to two more smaller tufts on its back. When the moth is at rest, the overall effect is of a kyphotic dandy in a moth-eaten fur coat.

It’s not its looks that make the Silver Y remarkable, though—it shares the essentials of these with several more strikingly patterned and colorful relatives in the noctuid subfamily Plusiinae, many autographed in similar fashion. Rather, it’s the moth’s capacity for flight. This is an insect less than an inch from nose to tail, and that tips the scales at not a hundredth of an ounce. Yet it’s capable of crossing a continent.

Silver Ys pass the winter as adults around the Mediterranean basin, in Southern Europe and North Africa. In spring, some of these moths head north, following the seasonal flush of resources. The first ones generally reach the UK in early to late May, although the main arrival occurs a few weeks later. Sometimes they appear in their millions—in such numbers that the sound of their wings can be heard as a distinct humming in the fields. They can occupy the whole country, from Kent to Shetland. They arrive hungry, and are a common daytime sight refueling on nectar like tiny hummingbirds. As a result, the Silver Y is one species of moth that is relatively familiar to the general public.

These immigrants come to breed, and they quickly get down to it. Their caterpillars can feed on—yes, you guessed it—a wide range of herbaceous plants, such as clovers, bedstraws, and nettles. They will consume crop plants like peas and beans, too, and can be considered agricultural pests. They enjoy the Northern European summer to the extent that come autumn, the spring immigrants can have quadrupled their population.

Silver Ys don’t like the British winter, though. When the nights draw in, it’s time for the new generation to head south. As many as seven hundred million of these moths stream back across the English Channel to the continent. You might think that such tiny creatures are simply being tossed on the wind, but they are not. They fly up to altitude— typically more than 100 yards above ground—and if they find the airflow there heading more or less south, they migrate. A tail wind helps, of course, but the moths are active migrants. They adjust their flight path to compensate for drift caused by winds not blowing exactly to the south, steering with an in-built compass. With the wind behind them, they can cruise at 25–30 miles per hour. They might cover more than 350 miles on a good night, and be in the Mediterranean after just three nights of travel. An insect that weighs about the same as a raindrop.

Entomologists can now track flying insects using vertical-looking radars, machines that send a narrow beam of radio waves up into the sky to detect the creatures moving through it. The numbers they record are staggering. A recent study over 27,000 square miles of southern England and Wales estimated that 3,370,000,000,000 insects—3.37 trillion—migrate over the region every year. That’s 3,200 tons of insect biomass. The great majority of these are tiny animals like aphids, but “large” insects like the Silver Y still contribute around 1.5 billion individuals to the total, or 225 tons. For context, the thirty million swallows, warblers, nightingales, and other songbirds that head south from the UK each winter tip the scales at about 415 tons. In summer, the insects are basically milling around in the air, but in spring they are generally heading north, and in autumn they are largely heading south. It’s not only Silver Ys that migrate.

Bird migration is one of the great natural spectacles, but insect migration is equally spectacular. It just largely goes unseen. There are myriad insects on the move above us at any one time. It’s only occasionally that we are confronted with the fact—like on July 10, 2016.

Exactly why moths are attracted to lights is still the subject of debate, but one reason may be that they use the moon or stars to help direct them as they migrate. The lights we put on then override these astronomical cues. A rule of thumb like “keep the moon on your right” can help to steer a more or less straight line, because the moon is very far way. Apply this rule to a street lamp, though, and the result is a flightpath that spirals into the source. The authorities at the Stade de France had left the floodlights in the stadium on overnight prior to the big game. They inadvertently created the world’s largest moth trap.

The Silver Ys added luster to what was generally agreed to be a turgid night of football. How wonderful that such swarms of insects still exist!

Excerpted from “The Jewel Box: How Moths Illuminate Nature’s Hidden Rules.” Copyright © 2023 by Tim Blackburn. Reprinted by permission of Island Press.