How a Woody Guthrie Poem Became Part of Chicano Activism

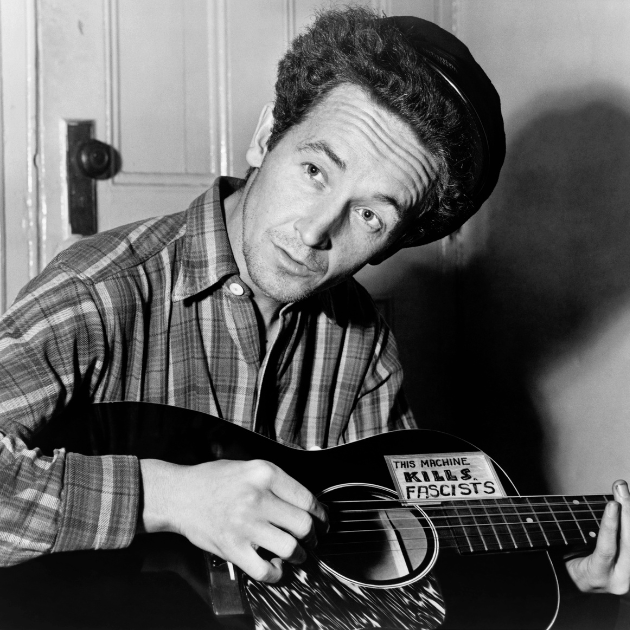

During WWII, labor shortages led the United States to launch a migrant worker program, bringing Mexican laborers, known as braceros, to farms and railroads across much of the country. In 1948, a plane carrying 28 laborers — some at the end of their contracts and others undocumented workers being deported — crashed near Los Gatos Canyon, California, killing everyone on board. While the white victims were returned to their hometowns for burial, the rest were buried unnamed in a mass grave. When folksinger Woody Guthrie heard a scant report listing only the four names of the white flight crew, it inspired him to write a poem that decried the dehumanization of these workers that continues to resonate today. The poem reads, in part: “Who are all these friends, all scattered like dry leaves? The radio says, ‘They are just deportees.’”

In this excerpt from his new book “Against the American Grain: A Borderlands History of Resistance,” (University of New Mexico Press, October 2024) cultural ecologist and environmental historian Gary Paul Nabhan draws a throughline from the poem to today, highlighting the profound way that writer and poet Tim Z. Hernandez has addressed the lament of Guthie’s words.

Back when Woody was barely nineteen, he spent time in the desert with some Spanish-speaking vaqueros on their way back to Mexico through the twin border towns of Presidio, Texas, and Ojinaga, Chihuahua. It seems that he wrote of this memorable encounter with migrants in his notebook at the time:

“Rosalita called out first to the cowboy and his horse, ‘Adios, Jesus!’ Carlos was louder, ‘Jesus, amigo, adios!’”

Seventeen years later, the names of his Mexican compañeros who had headed back across the border must have stirred in his memory as he read a ninety-word dispatch released on January 28, 1948. It carried the headline “32 Are Killed in California Plane Crash.”

Woody read on, trying to imagine the disaster in palpable, personal terms. Of the thirty-two killed in Los Gatos Canyon in western Fresno County, twenty-eight were Mexican deportees whose charred bodies “were mangled beyond recognition.” They were undocumented workers being flown back to the Mexican border. Although the Anglo flight crew members were named, mourned, and buried in separate graves in their hometowns, none of the names of the farmworkers killed in the crash were included in any English-speaking newspapers covering “the worst aviation accident in California history.”

Woody was shocked to read a short newspaper account that revealed only the names of four Anglo Americans who had died in a terrible plane crash in Fresno County, California, without mentioning a single name of the twenty-eight Mexican farmworkers who were killed while being deported on that same plane:

Who are all these friends, all scattered like dry leaves?

The radio says, ‘They are just deportees.’

When he tried to evoke some possible Spanish names to fill in the blanks, Jesus and Rosalita from down by Presidio along the Big Bend must have popped into his head:

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye Rosalita,

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria,

You won’t have a name when you ride the big airplane

All they will call you will be deportees.

•••

Woody’s handwritten poem stayed in a shoe box for years until it was included in a volume of lyrics of American “protest music,” even though Guthrie himself had never offered a tune to any of his friends to go with the lyrics.

Instead, a young folk singer from Arizona named Martin Hoffman came up with a melody for Woody’s “Deportee” poem years later. Martin had the chance to sing it to Woody’s close friend Pete Seeger, who loved it. When Seeger’s version was recorded — attributing it to the team of Guthrie and Hoffman — dozens of other artists began to sing it, first in English, then in Spanish as well.

By 1966, brothers Luis and Danny Valdez began to sing their Spanish translation of Woody’s poem to crowds of farmworkers rallied together by Dolores Huerta and César Chávez. The Valdez brothers’ Banda Calavera sang for their Teatro Campesino, recording just one of forty-some versions of “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos (Deportee)” that have reached the American airwaves.

The short poem that Woody never personally recited nor sang anywhere in public somehow became the most popular song of lament for Spanish-speaking farmworkers ever to emerge from the American earth.

The short poem that Woody never personally recited nor sang anywhere in public somehow became the most popular song of lament for Spanish-speaking farmworkers ever to emerge from the American earth. It is perhaps his most widely covered song, with versions by bestselling artists such as Byrds, Dolly Parton, Johnny Rodriguez, Odetta, Nana Mouskouri, and Joni Mitchell. It was probably the last great song Woody would write during his career.

But within a year of the Valdez brothers taking the Spanish translation on the road to give voice to migrant farmworkers’ lucha, Woody’s own capacity for speaking and singing had dramatically deteriorated.

•••

The very degenerative disease that had crippled and killed his own mother had begun to disrupt Woody’s own behavior as early as 1952. It had gotten completely out of control by the mid-1960s, for he would forget where he lived and disappear for days before someone recognized him sleeping in a park or a Skid Row alley.

The timing of the onset of his illness was ironic, for it hit him hard just as a resurgence of interest in his artistic and political work began to surge. By the time Woody was belatedly diagnosed with an incurable, inheritable malady called Huntington’s disease, the psychoneurotic consequences from it were immense.

Woody — the insatiable drifter, incurable rambler, and restless radical — would spend the last third of his life bedridden, hospitalized, and increasingly unable to sing his way completely through any of his own tunes. He died of his prolonged illness in 1967 at the age of fifty-five, leaving more than a thousand unnervingly poignant songs behind him.

Despite the acclaim that “Deportee” continued to receive after his death, Woody would never glimpse the impact it had generated and would never know the real names of those who were scattered like dry leaves.

•••

Those near-forgotten Spanish names continued to remain hidden from view for decades longer. At some point, it was simply assumed that anyone who had personally known those killed in Los Gatos Canyon had also passed, leaving little or no glowing embers to rekindle.

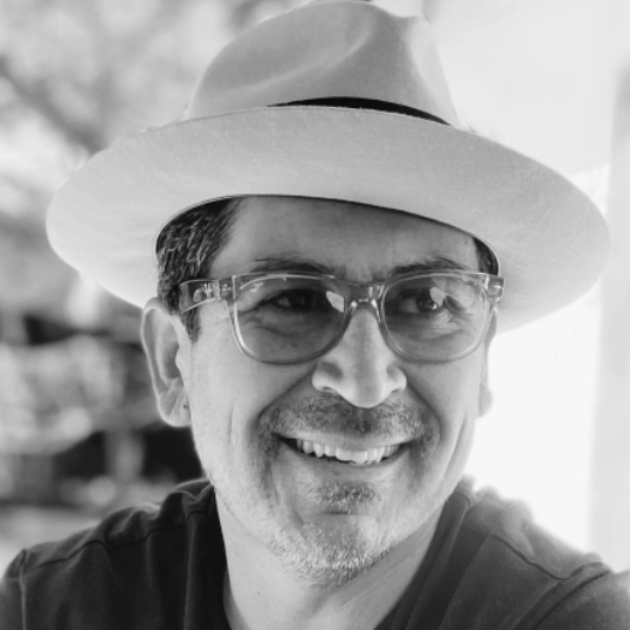

That assumption was faulty, as poet and oral historian Tim Z. Hernandez soon confirmed. Tim took on years of work to crack the code of this mystery and daylight the names of those who had been forgotten by history.

Hernandez found a way to take a one-sided story of a tragic event that had devastated dozens of families on both sides of the border and make the narrative whole. His work generated a kind of belated healing for many of the survivors of those who had been scattered like dry leaves.

Hernandez found a way to take a one-sided story of a tragic event that had devastated dozens of families on both sides of the border and make the narrative whole. His work generated a kind of belated healing for many of the survivors of those who had been scattered like dry leaves.

Over the decades since Woody’s illness and death, many have tried to pair his work with the likes of Leadbelly, Cisco Houston, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, or even that of Arlo, Woody’s son. But in Woody’s wake, only Tim Z. Hernandez was tenacious, courageous, and compassionate enough to let the dust from the 1948 plane wreck settle so that families could at last see what had been kept out of view for decades.

Tim Z. Hernandez understood dust. He grew up in it, swallowed it, cleaned it out of nostrils and ears, and wrote poems about it. Tim’s debut novel was entitled “Breathing, In Dust.”

Tim is the grandson of a Dust Bowl–era farmworker not all that unlike those who died in that devastating crash at Los Gatos Canyon. As he mourned in his poem, “Variations on This Land,”

This land is my grandfather’s land

whipped to suffer his color in the cumin air,

to erase that he ever loved, the way only a brown boy

can love Brownsville, beneath oil derricks

and sugarcane horizons, and fields

of afterthought, a cluster of cancerous

lovers in the wake of red dust . . .

In talking with Tim on one of his trips through the desert from El Paso to Tucson, I realized that much of his work as a poet, novelist, and oral archivist gravitated toward revealing the hidden side of some stories that had been told in a one-sided way for decades.

In doing so, Hernandez had found a way to move those affected by physical tragedies and racist behaviors toward places of pride and dignity about their families’ contributions to American history. When told carefully and considerately, those full-bodied stories could help close wounds that had been festering for years.

When you hear Tim himself tell how he tracked down so many dry leaves that had scattered over the decades, you inevitably wish that Woody could have heard the answers that Tim found to Guthrie’s nagging question.

Tim’s poetics and ethics, his craft as performance artist, and his uncanny luck on wild goose chases have forever changed how people will hear Woody’s second most popular song.

It was Tim who brought the widows and descendants of those twenty-eight “once nameless” farmworkers together to affirm the names that were finally placed on a memorial in Fresno County Holy Cross Cemetery. And it is Tim who continues to record the stories from those who had been lost as a gesture of healing.

At last, a kind of spiritual and social justice has emerged from bringing together the two sides of that unspeakable tragedy. What Woody began, Tim has brought closure to in a manner just as poetic, empathetic, and prophetic.

In doing so, Tim Z. Hernandez deserves the same stature as a national treasure as that which Americans of all races have given to Woody, the Folkiest of the Folksingers, the Rowdiest of the Rounders, and the Dustiest of the Dust Bowlers. Maybe someday, Tim Z. Hernandez will be remembered as the most Resonant of Razafirme Poets, the Dustiest of the Atzlán Descendants, the Cheekiest of Chicano Activists, the most Open-Eared of Latinx Oral Historians, and the Two-Sidedest of all Desert Borderland Storytellers.

Not only does Woody live on in Tim’s work but so do the lives and loves of twenty-eight Mexican farmworkers who might have otherwise been lost to history.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from “Against the American Grain: A Borderlands History of Resistance” by Gary Paul Nabhan, published by University of New Mexico Press, Oct. 2024.