‘Nursery Earth’: The Bizarre Behavioral and Developmental Adaptations of Caterpillars

Bioneers | Published: November 13, 2024 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

Why pay attention to baby animals? From egg to tadpole, chick to fledgling, they offer scientists a window into questions of immense importance: How do genes influence health? Which environmental factors support ― or obstruct ― life? Entire ecosystems rest on the survival of animal babies. At any given moment, babies represent the majority of animal life on Earth.

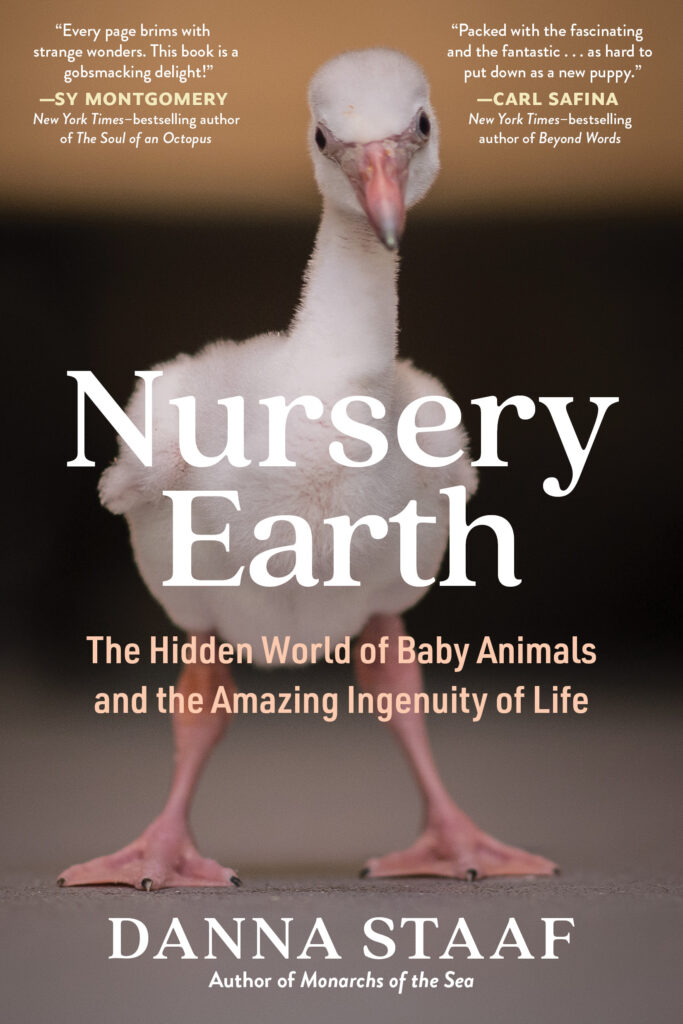

In her book “Nursery Earth,” marine biologist and researcher Danna Staaf explores what scientists know about these tiny, hidden lives, revealing some of nature’s strangest workings: A salamander embryo breathes with the help of algae inside its cells. The young grub of a Goliath beetle dwarfs its parents. The spotted beak of a parasitic baby bird tricks adults of other species into feeding it.

In a conversation with Bioneers, Staaf said she was motivated to write “Nursery Earth” in part because she wanted people to realize that baby animals are not just miniature versions of their full-grown counterparts but instead their own, distinct creatures.

“I wanted people to see that babies are not just incomplete adults,” Staaf said. “They’re adapted to doing different things, to thriving in their own environment.”

Caterpillars, the larval stage of butterflies and moths, offer an obvious example. But even before their dramatic metamorphosis, these insects are changing and adapting. In this excerpt from “Nursery Earth,” learn about the amazing capabilities — from mimicking bird droppings and snakes to shooting their feces 40 times the length of their bodies — that caterpillars employ to survive this precarious stage in their life.

Staaf has a doctoral degree in biology from Stanford University, where she studied baby squid. She is the author of several books, including “The Lives of Octopuses and Their Relatives: A Natural History of Cephalopods,” “Monarchs of the Sea,” “The Lady and the Octopus” and “Nursery Earth.” Hear more from Staaf about what shapes and motivates her work in this Q&A with Bioneers.

The following is an excerpt from “Nursery Earth” by Danna Staaf (The Experiment, June 2023).

The bizarre behavioral and developmental adaptations of caterpillars

“It’s not easy being a caterpillar,” says the ecologist Martha Weiss of Georgetown University. “Lots of people want to eat you, and lots of people want to lay their eggs inside of your body.”

If you’re thinking the latter part of that statement sounds like a reference to parasitoid wasps, then you are absolutely correct. After decades of studying caterpillars, Weiss says she isn’t surprised if half the ones she collects in the wild turn out to be parasitized by wasps or flies. When they pupate, “instead of one butterfly, you get a thousand wasps.” It’s even possible for the parasitoids to parasitize each other inside the caterpillar. “It’s a turducken of larval development happening at once,” Weiss tells me, rather gleefully.

Although caterpillars are insects and technically have a hard exoskeleton, it’s so thin and flexible it doesn’t offer much protection from predators. However, some caterpillars have adapted it into an unusual defense. They have to molt as they grow, shedding the old skin (each molt marks a new instar, or phase of larval development). Many insect larvae hold on to their old molts in order to deter predators, and I agree it is quite a deterrent. I would not eat a mad hatterpillar, which stacks its old heads atop its current one, no more than I would eat a golden tortoise beetle larva, which carries its feces as well as its old skins on a structure called an anal fork.

I would not eat a mad hatterpillar, which stacks its old heads atop its current one, no more than I would eat a golden tortoise beetle larva, which carries its feces as well as its old skins on a structure called an anal fork.

Other larvae cycle through a variety of predator-repelling tactics as they grow. The caterpillars of two swallowtail species at first resemble bird droppings, in mottled white and brown. After a couple of molts, they switch to mimicking snakes, vivid green with large imitation eyes. “You can’t be bird poop if you’re three inches long, but you can be a nice snake if you’re three inches long,” explains Weiss. These fake snakes even change their behavior, puffing up their shoulders and flicking out a pretend “snake tongue” to really sell the disguise.

Although Weiss is well versed in the world’s diversity of caterpillars, she has devoted her career to one species in particular: the silver-spotted skipper. With characteristic dry humor, she says, “Nobody knows more about silver-spotted skippers than I do. Not many people know or care about silver-spotted skippers, so I’m not giving myself too great an accolade there.”

Weiss’s work on this species has revealed fascinating adaptive characteristics. It is one of a few caterpillars that engineer shelters for itself from both the surrounding foliage and its own extruded silk. At each instar, a skipper caterpillar produces the same precise leaf shelter as other caterpillars in the same instar. They make the same cuts, the same folds, the same stitches with silk to hold the shelter’s shape. They spend most of their time resting in this shelter, periodically emerging to eat and to expel their feces. And they don’t just poop on the leaf or hang their butt over the edge and poop on the ground. No, they shoot their poop with incredible force over a distance that can be forty times their own length. This defensive maneuver avoids bringing their little house to the attention of predators who might see or smell an accumulation of waste nearby.

After studying silver-spotted skippers for twenty years, Weiss is always ready to help new students learn to identify the five instars of caterpillar development. But she found these entomologists-in-training repeatedly coming to her with one particular problem: how to determine if certain caterpillars were in the third or fourth instar. “It always made me feel kind of incompetent when I would look at these, and I couldn’t really tell what was going on,” she says.

Finally, one of the scientists in the lab who was tracking the individual development of caterpillars day by day discovered the existence of an extra instar. Some of these caterpillars were going through a “third-and-a-half” instar, bigger than the third but smaller than the fourth. This extra instar only shows up in stressful conditions, when food or weather aren’t optimal. But just because it’s conditional doesn’t mean it’s uncommon—there are times when over half the caterpillars on a given plant will exhibit the extra growth stage.

Weiss takes this experience as a crucial reminder that we limit our understanding when we hold on too tightly to what we think we know.

Weiss takes this experience as a crucial reminder that we limit our understanding when we hold on too tightly to what we think we know. Textbooks and published papers had all described five instars in silver-spotted skippers, so when Weiss and her students saw caterpillars in the extra instar, they kept “trying to mash them into one box or another.” Many aspects of this caterpillar’s biology are precise, rigid, and predictable. Each leaf-and-silk shelter is produced in narrow tolerances as though on an assembly line; each propulsive poo travels farther from the shelter the older and larger the larva becomes. These adaptations help protect skipper caterpillars from predators. The flexibility of their development is a different kind of adaptation, a baked-in capacity to cope with other kinds of environmental stress. It reminds us that adaptation isn’t something that happened in the past and is now finished—adaptation can be flexible and ongoing.

Excerpt from Nursery Earth: The Hidden World of Baby Animals and the Amazing Ingenuity of Life © Danna Staaf, 2024. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, The Experiment. Available everywhere books are sold. theexperimentpublishing.com