Revealing Hidden Histories: Daniel Coe on the Art and Science of Mapping Rivers

Maps have the power to do more than guide us—they can tell stories, reveal hidden histories, and inspire deeper connections to the natural world. For cartographer and artist Daniel Coe, this storytelling is at the heart of his work. As the graphics editor for the Washington Geological Survey, Daniel creates stunning visualizations that not only aid in understanding natural hazards and geology but also uncover the dynamic beauty of landscapes, particularly rivers.

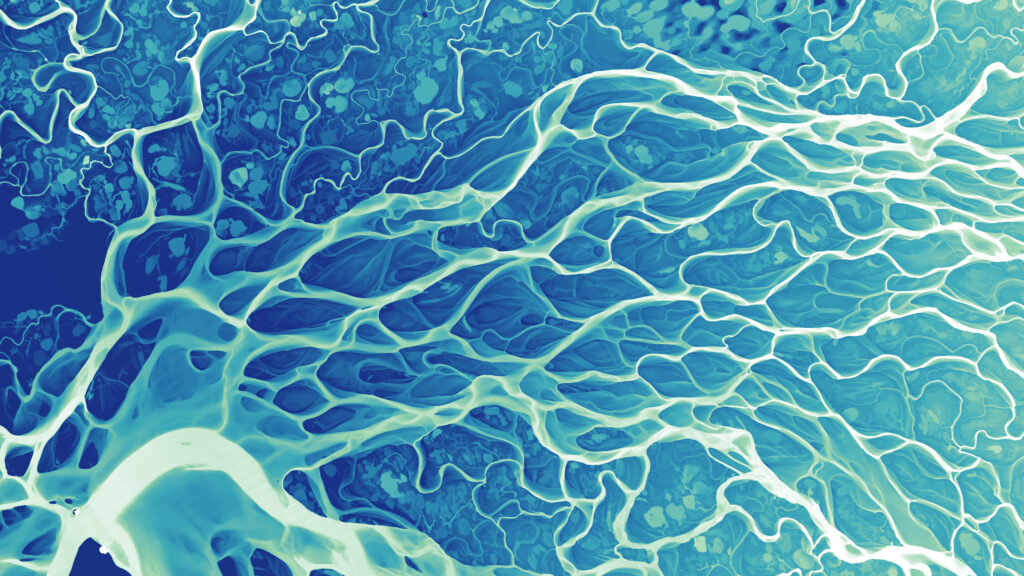

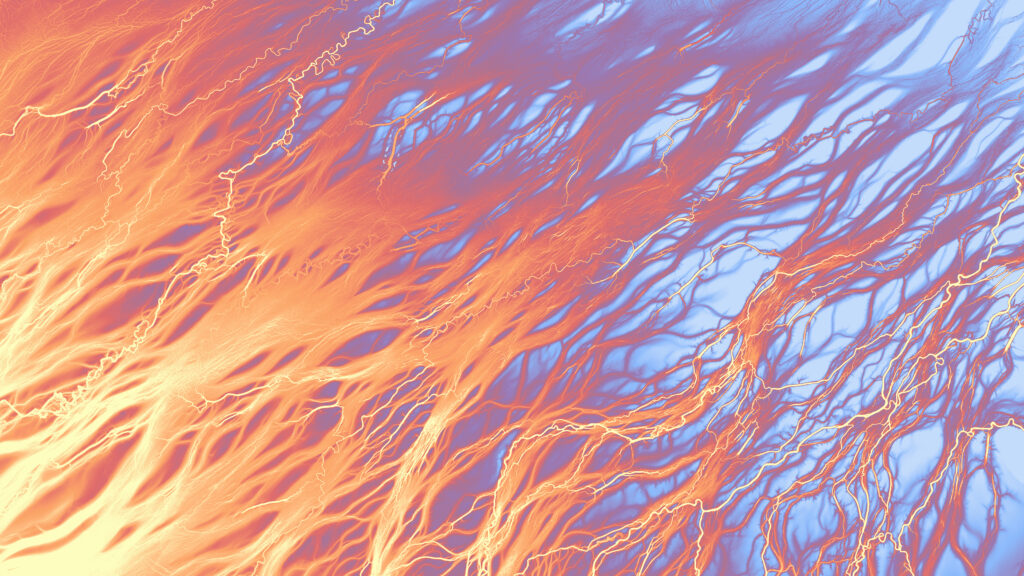

Daniel’s innovative use of LiDAR data has captured attention far beyond the world of geology. His vibrant, multilayered river maps—including one featured in the Bioneers 2025 key art—blend science and art, inviting us to see the rivers around us in ways we never have before. With a background that includes work with the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, contributions to the Atlas of Design, and collaborations with artists and scientists alike, Daniel brings a unique perspective to his craft.

In this conversation with Bioneers President Teo Grossman, Daniel shares insights into his creative process, his passion for rivers, and how his LiDAR-based images provide a deeper sense of time and place.

TEO: I’d love to start by asking how you describe what you do.

DANIEL: I work as a graphics editor for the Washington Geological Survey, so basically anything visual that our survey produces, I usually have a hand in. Most often, that’s in the form of maps. My main role is as a cartographer.

I love maps. I love making maps. I love getting creative with maps. At the Survey, we deal with a lot of natural hazards, like landslides, earthquakes—mapping things like that. We also map the geology of the state and are the center point for collecting LiDAR data in Washington.

I also began to make lidar river images outside of Washington in the past several years. This river series grew out of a desire to learn how to use different software and to have a project that has no creative restraints. I can do whatever I want. I can make bright, crazy colors. They don’t have to mean anything. It’s just me following my creative intuition.

I’ve gotten a bit obsessed. I love being around rivers, on rivers, floating rivers. It’s so neat what you can see with this data. It’s showing rivers in ways they’ve never been seen before, which is super exciting to me. It’s satisfying to make them for my own purposes, but it’s also satisfying that other people appreciate them, learn from them, and gain a better appreciation for the rivers where they live through them.

TEO: A lot of people might not be familiar with LiDAR. Could you explain what it is and what kind of results it produces?

DANIEL: LiDAR stands for light detection and ranging. It’s a technology that uses a high-tech laser range finder to collect three-dimensional information.

The kind of LiDAR that I use is generally collected from an airplane. They fly a small airplane over the ground, and there’s an instrument that shoots lots of pulses of light at the ground. That reflects back up to a sensor. We can take that information, all of those points where the light hits the ground or a tree or a house, and collect them into what is called a LiDAR point cloud. We can create three-dimensional models of the Earth with a point cloud; surfaces that have all the trees, houses, and buildings included. However, the interesting thing, from my perspective, is that we can remove all of that stuff on the surface and only view the bare ground. That’s really powerful for seeing different types of landforms, but it’s most interesting to me for seeing floodplains. We can see where rivers have meandered in the past. We can see subtle changes in elevation and topography, which often capture really old stream meanders, sometimes hundreds or thousands of years old.

TEO: When we look at the river images Bioneers is using, what exactly are we seeing?

DANIEL: The colors in the images represent elevation in different ways. Often I’ll start with a gradient that goes from a light color to a dark color. The light color usually represents the river surface, and then everything that gets darker progressively represents elevations that are higher above the river. When you represent the landscape in that way, you can often see around the river the places where it flowed in the past that are at a slightly higher elevation.

It produces this really interesting effect. You have this static image, but it also represents the river in multiple dimensions, like the dimension of time. I often see other things in these channels, like trees or lightning or smoke. They often evoke other sorts of forms of nature. There are even some analogs with the human body, especially in river deltas, where everything spreads out into multiple channels. A fractal nature emerges, a repeated pattern over different scales.

TEO: It’s a reminder that we have our own internal biological hydrology that mirrors the external world in some ways. This blend of scientific data and artistic expression is fascinating. Do you get feedback from scientists about the utility of these images?

DANIEL: I get a ton of feedback from geomorphologists on the usefulness and the beauty of them. You can see all sorts of things in these images—in a big river system like the Mississippi River, you can see where rivers have been leveed because those elevations are a little higher, so they often produce darker lines. That’s also a really good jumping-off point for talking about how rivers have been constrained by humans.

TEO: It really is evocative when you consider the challenges that humans have in managing landscapes. A lot of the environmental issues we deal with really boil down to humanity’s lack of ability to think in terms of time frames outside of our own. As a species, we’ve evolved to be adaptable, and we adjust to a “new normal” frighteningly quickly.

DANIEL: One thing about geology in general, but also about these images, is they give you that deeper sense of time. It can be humbling to think about, “This river has been moving all over for thousands of years, and I’ve only been here for a tiny portion of that time.” Yet, as humans, we have this outsized influence. We can put a dam on a river or hem in a river with levees. There are societal benefits to some of those things, but is the trade-off and the cost to that overall ecosystem worth it? I think it puts our relatively short lives in a better perspective in relation to the rest of the Earth.

TEO: I saw that one of your images is featured as the internal jacket cover for Robert Macfarlane’s new book “Is A River Alive.”

DANIEL: I’m super excited about that. I’ve been looking forward to that book. The concept is about the personhood of a river. These images really show how the river is alive because it’s moving all over the place. It kind of has its own will, so to speak.

TEO: Are there other artists and image-makers doing similar work that you admire?

DANIEL: There’s an artist named Brad Johnson who does amazing work with LiDAR data. He uses point clouds and animates them in this really interesting way that brings out the nature of geology in different places. He does really incredible installations. He also creates animations that are choreographed with live music. It’s just a really powerful way to experience that sort of data.

TEO: Are there other maps that, as a cartographer, you really admire?

DANIEL: There are tons. Historically speaking, there are maps by Marie Tharp, who helped push the idea of plate tectonics. She mapped the undersea ridges in many of the oceans, and she partnered with cartographer and painter, Heinrich Berann, to create these absolutely beautiful maps. They were published in National Geographic. I remember looking at my parents’ old National Geographics as a kid and seeing these beautiful maps and just being blown away by them.

TEO: The work you do is really spectacular and I’m sure that kid pouring over old maps would be thrilled with how things turned out, decades later.

DANIEL: Definitely. Hopefully there’s somebody out there who’s seeing these right now and thinking, “Ooh, that’s cool, I want to do something like that when I grow up.” That would be the most satisfying thing ever.