What an Owl Knows: Rethinking Bird Brains & Intelligence

Bioneers | Published: February 20, 2025 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

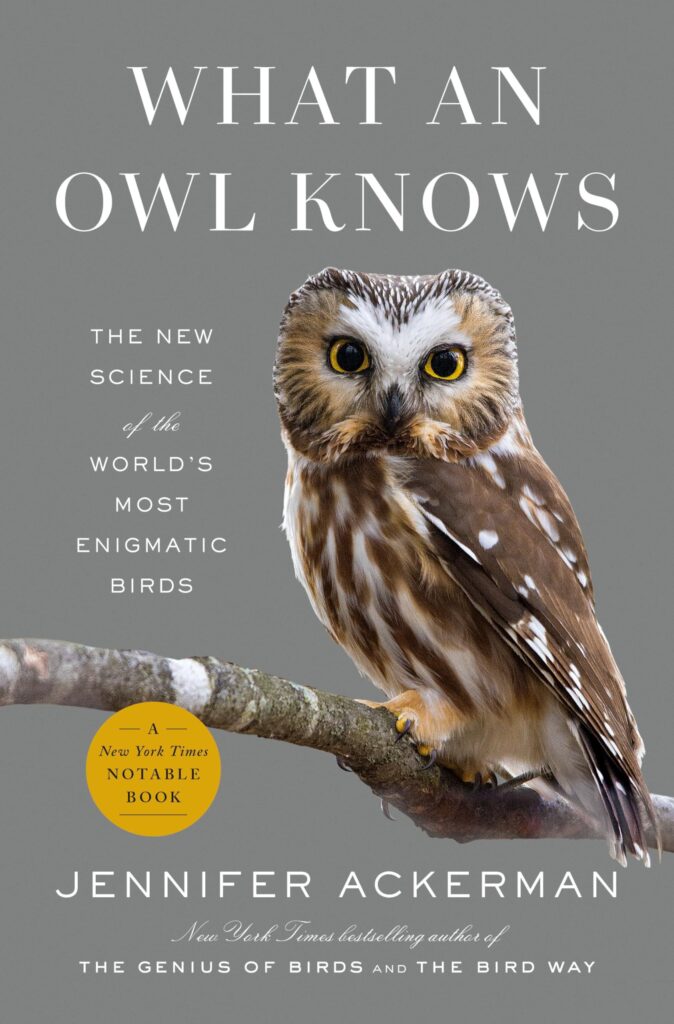

With their forward gaze and quiet flight, owls are often a symbol of wisdom, knowledge, and foresight. But what does an owl really know? And what do we really know about owls? “What an Owl Knows” by Jennifer Ackerman tells the extraordinary story of how we’ve come to understand owls, their biology, brains, and behavior, and explores many of the surprising new scientific discoveries: how owls talk to one another, how they ‘see’ sound, how they court their mates in wild and outlandish ways and fiercely protect their nests, how they migrate huge distances and survive the radically changing conditions of our planet.

In the following excerpt from “What an Owl Knows,” Ackerman delves into the cognitive abilities of owls and what they can teach us about our own measures of intelligence. You can read more from Ackerman about owls’ impressive abilities, adaptations and “ways of knowing” in this conversation with Bioneers.

Jennifer Ackerman is an award-winning science writer and speaker, and the New York Times bestselling author of “What an Owl Knows,” “The Bird Way,” and “The Genius of Birds.”

From WHAT AN OWL KNOWS The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds by Jennifer Ackerman, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Jennifer Ackerman.

We used to think all birds were simple-minded, flying automatons, driven solely by instinct, and that their brains were so small and primitive they were capable of only the simplest mental processes.

An owl’s brain, like most bird brains, would easily fit inside a nut—a fact that gave rise to the derogatory term birdbrain. But we’ve known for some time that brain size is not the only—or even the main—indicator of intelligence. And the truth is, most owls have relatively large brains for their body size, just as we humans do. Scientists recently proposed the origin of their big brains: parental provisioning, parents feeding their young during a critical period of their development. When a group of animals called the “core land birds” (songbirds, parrots, and owls) arose some sixty-five million years ago, the theory goes, they brought with them something extraordinary: altricial young, chicks that are hatched in an undeveloped state, requiring parental care. With that trait came extensive parental provisioning of those immature young, which resulted in notably large brains in some bird lineages, including parrots, corvids (ravens, crows, and jays), and owls.

Size aside, bird brains have also gotten a rap because of a perceived difference in their architecture—an apparent lack of a layered cerebral cortex like ours—reinforcing that once-derisive view. The neurons in the cortex-like part of bird brains (called the “pallium”) are arranged in little bulblike clusters, like a head of garlic, whereas our neurons are arranged in layers, like a lasagna. We thought that an animal needed a layered cortex to be intelligent. But new research shows that the bird pallium is in fact organized a lot more like the mammalian cortex than we first imagined.

Moreover, scientists have discovered that what really matters in the intelligent brain—however it may be organized—is the density of nerve cells, or neurons. And while the brains of birds may be small overall, it turns out that in many species, they’re densely packed with neurons, small neurons. This gives the brains of some birds, such as parrots and corvids, more information-processing units than most mammalian brains and the same cognitive capabilities as monkeys, and even great apes. The more neurons there are in a bird’s pallium, regardless of its brain or body size, the more capable it is of complex cognition and behavior.

Also critical to intelligence is the connections between neurons—how they’re networked, wired together. And in this way, bird brains are not so different from our brains, with some very similar neural pathways. For example, to learn their songs, songbirds use neural pathways that are similar to those we use to learn to speak. Crows use the same neural circuits we use to recognize human faces.

More and more, the pillars of difference between our brains and those of birds are toppling. The latest to go is the capacity for consciousness. A 2020 study of Carrion Crows suggests that bird brains possess the neural foundations of consciousness. “The underpinnings are there whenever there is a pallium,” says neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel.

All of this is humbling and suggests we still have a lot to learn about bird intelligence.

But owls? The knock on owls is that most of the cortex-like part of their brains is dedicated to vision and hearing, some 75 percent, in fact, which supposedly leaves only a quarter for other purposes.

Not long ago, scientists conducted a classic test of intelligence on Great Gray Owls. The so-called string-pulling paradigm is widely used to test problem-solving skills in mammals and birds. The task requires animals to understand that pulling on a string moves a food reward to within reach. Crows and ravens peg the test easily. The experiment showed that Great Grays presented with a single baited string failed to comprehend the physics underlying the relationship between the objects—that is, they didn’t grasp that pulling on the string would move the food toward them.

But really, is this a fair test of an owl’s intelligence? As Gail Buhl remarks, “It’s kind of like telling a rabbit, fish, or antelope that in order to pass an intelligence test, they have to climb a tree.”

Owls may not be smart in the ways crows are smart, in the ways we are smart, devising technical solutions to physical problems or comprehending the physics underlying object relationships. But this may only point to the limitations of our own definitions and measures of intelligence.

Little Owls are a symbol of wisdom, companion to Athena, the ancient Greek goddess of wisdom. Pavel Linhart points out that there may be something to this. The Little Owls that Linhart studies recognize people, distinguishing between the farmers they’re used to seeing several times a day and the researchers who sometimes band them, check their nest boxes, or observe them through binoculars, and behaving differently around the two types of people. With the farmers, they’re relaxed and don’t take off as quickly as they do with the ornithologists. “These owls are also very curious and investigate their environment,” he says, which can make them vulnerable to certain traps around human settlements—vertical pipes, ventilation tubes, hay blowers, chimneys, etc.—they can get in but can’t get out. (So curiosity can also kill an owl.)

Ask ornithologist Rob Bierregaard whether owls are smart, and he’ll tell you a story about wild Barred Owls. He trains the wild owls to come to a whistle so that he can tag them with a GPS tracker or retrieve the device. “I’ll put a mouse out on the lawn, and when they come down to catch it, I’ll whistle,” he explains. “Then I’ll put out another mouse and whistle, another mouse and whistle. After three mice, they’ll come when I whistle.” The owls learn this in a day, and it never takes longer than three sessions to get a bird completely trained. “I’ve had birds that were waiting for me the day after I trained them,” he says. “So my IQ assessment is based on how quickly they learn that a whistle means free mice.”

Bierregaard remembers one owl with an impressive memory for the training. “We called him Houdini because he got out of every trap that we could put up,” he recalls. “Three or four years after I first lured Houdini with mice, I went back to his woods to look for him. I whistled, and he came in. It had been years since I’d been in his woods, and he remembered that whistle!

From WHAT AN OWL KNOWSThe New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds by Jennifer Ackerman, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Jennifer Ackerman.