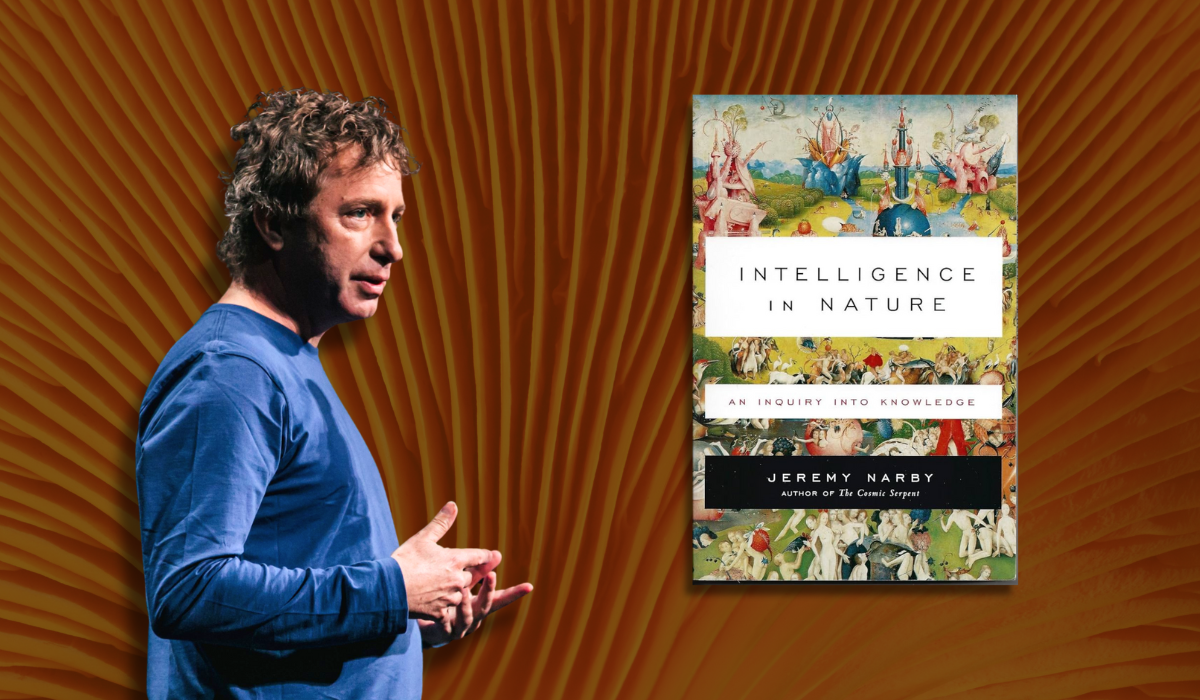

Jeremy Narby on Intelligence in Nature, 20 Years Later

Bioneers | Published: March 11, 2025 IndigeneityNature, Culture and Spirit Article

Two decades ago, Jeremy Narby challenged conventional thinking with his book Intelligence in Nature, exploring the cognitive abilities of plants, animals, and other living systems. Since then, science has rapidly advanced—and much of what was once considered fringe is now mainstream. In this conversation with Bioneers Senior Producer J.P. Harpignies, Narby reflects on the book’s legacy, the ongoing battle over nature’s intelligence, and how Indigenous knowledge and Western science can (or can’t) be reconciled.

Narby is also the author of The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge (1998) and co-editor of Shamans Through Time with Francis Huxley.

This interview, conducted on Feb. 18, 2025, has been edited and excerpted for clarity.

J.P. HARPIGNIES: Jeremy Narby, thanks so much for doing this. Before we jump in, I wanted to just explain to our readers why we wanted to interview you on the 20th anniversary of the release of Intelligence in Nature. The main reason is that we at Bioneers felt that the book was far ahead of its time and wasn’t done justice by the reviewing community and the general public when it came out, but it was an important marker for us, and hopefully it will get more attention (or at least historical recognition) going forward.

I wanted to go over a few of the themes of the book for those who are less familiar with it or haven’t read it in quite a while. It seems to me that there are three main topics of your book. One is a travelogue: you took journeys to go meet scientists around the world who were working at the cutting edges of studying cognition and decision-making among a wide range of other-than-human species. The second aspect of the text was a further exploration of a core theme in your life’s work—the comparison between shamanic ways of perceiving the world and Western scientific ways, and exploring if there’s any way to reconcile those different cognitive approaches. And finally, the subtitle of the book indicates that it was also an inquiry into the mysteries of the mind, of how we can even know what we know. Those were the three big themes, in my estimation.

And I wanted to start with your visits to scientists’ labs around the world. These included Charlie Munn observing Amazonian macaws in the field; Anthony Trewavas studying plant cognition; Martin Giurfa in Grenoble proving bees understood abstract symbols; and your trip to Japan to visit two scientists, one studying the amazing visual capacities of butterflies, and the other one slime molds’ astonishing capacities to solve mazes. And you also mentioned a lot of different studies of sponges, amoebas, nematodes, octopuses, parrots, leaf-cutter ants, etc.: there was quite a lot in there.

It was pretty clear in all your conversations with these scientists that the old Cartesian model of animals as dumb automatons and humans as the only ones possessing intelligence was already crumbling in the scientific world, but they were still somewhat outliers, and there was still some hesitancy in using the term intelligence. But since your book came out, there’s been an avalanche of every week yet another finding by another scientist studying yet another species’ exhibiting intelligent behavior. Just to mention a handful who have been at Bioneers, we had Suzanne Simard studying trees communicating and sharing nutrients and information through mycelial webs; and speaking of mycelial webs, Merlin Sheldrake and Toby Kiers and the group at SPUN doing extraordinary work studying the decision-making capacities of mycelial networks; and we had Monica Gagliano who discussed her experiments showing that plants could recognize sounds and react to them appropriately. And at this coming conference, we’re going to have Project CETI, the Cetacean Translation Initiative, the marine biologists using AI to decode whale language; the point being that there’s so much work that’s been done these past two decades in this domain.

So, do you feel vindicated after all these years, first of all, or do you just feel pissed off that your book wasn’t more widely recognized at the time? And secondly, do you feel that the battle has been won re: the breakdown of the old Cartesian model, that sort of cognitive anthropocentrism, or do you think there’s still a lot of entrenched resistance to the idea of intelligence permeating the natural world?

JEREMY: Well, that’s a handsome and generous question, because feeling vindicated or pissed off are two pretty good options, but, strangely, neither—I was never pissed off, in fact, because I knew that it was, let’s say, from the start, a kind of an outsider discourse that was meant to make people think and question their own categories, concepts, and presuppositions. It was a book for Westerners, even, let’s say, Western materialists—who grew up like I did, thinking that plants were just kind of thermostats or things. Yes, they had osmosis, they did things such as growing or absorbing water and nutrients, but it all happened by normal physical, chemical processes, as they used to say. I mean all of life was supposed to be just a normal physical, chemical process back at that time, but especially plants, because we’re talking the 1990s, early 2000s. It was already clear that there were animals such as dolphins and primates that were more than just the kind of machines that Descartes had in mind 400 years before. But plants were still pretty much forbidden territory. If you started talking about plant intelligence or plant decision-making or plant behavior even, people would start rolling their eyes and start suggesting that you’d taken too much of that Amazonian liana thing.

And I was always coming at it as an activist for the rights of Indigenous Amazonian people, and part of that work was to get their way of knowing the world, their Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous science, whatever, to be better understood and appreciated. I mean, Western science has been using Indigenous knowledge for a long time, using the plants identified by Amazonian people, but there again the attitude was always something like: “Well, they’ve been living there a long time, they’ve had enough time to wander around the forest and identify a few things that work, and there’s nothing very mysterious to it.” There always had been that kind of tendency to disparage what Indigenous people knew, while at the same taking their remedies from them, thank you very much, and patenting them and so forth, all of that late 20th Century scene.

And my whole point was to say that these people have a sophisticated way of looking at plants and animals, and they do live, after all, in the world’s most intense environment, the Amazonian Rainforest, with the greatest number of species, many of which Western science hardly knows or doesn’t even have names for. There are more names for plants in Amazonian Indigenous languages than in Latin given by scientists, and that’s still true today, but do they know more about plants than we do? Well, actually, the problem for mainstream science is that they talk about plants as if they’re people. According to the Indigenous vision, powerful plants such as tobacco have a personality or a “mother,” an owner, and to modern science, that is anthropomorphism, a cardinal sin.

The basics of Indigenous knowledge often sort of flew in the face of the basic tenets of Western science, but it’s clear that these people have impressive knowledge about all these different plants that we don’t even have names for. And when you asked them how they learned what they knew about plants, they’d invariably say: “We have these ayahuasquero, tobaqueros who eat psychoactive plants, and, in their visions, they communicate with the owners or the personalities of these plants that are powerful entities. Each species has one.” But that way of knowing, even though it leads to these concrete results, is not considered kosher by Western science. You’re saying you’re taking hallucinogens and that in your hallucinations you’re learning about the fundamental principles of these different organisms. That can’t be true; it’s an epistemological impossibility; you’ve got to be nuts if you believe that. In other words, that’s the definition of psychosis—taking your hallucinations seriously.

If you’re steeped in a modern rationalist/materialist worldview, when you try to make sense of what the Amazonian people say about their knowledge about plants and animals, you run into the limits of your own system of knowledge.

So, if you’re steeped in a modern rationalist/materialist worldview, when you try to make sense of what the Amazonian people say about their knowledge about plants and animals, you run into the limits of your own system of knowledge. Personally, I always thought that was interesting. It was kind of scary, because I had to write a doctorate at Stanford at the time, and admitting to taking the hallucinatory knowledge of Indigenous Amazonians seriously in 1986 would probably not have led to getting my Ph.D.

But to get back to the context of the book. I had written Cosmic Serpent ten years before. This year is the 30th anniversary of that text. That was a pretty radical work. In Intelligence in Nature, I wanted to tone it down a bit and to go visit scientists rather than shamans because it seemed to me that what many of these cutting-edge researchers were saying about their recent findings resembled what shamans had been saying all along, so in a way it was a sort of attempt at a Trojan Horse, using what scientists were saying to reveal the wisdom of what shamans had long held.

And, this may sound strange, but, also: I believe in science. In general, I’m not that interested in believing; I’m more interested in knowing, but I really do think, deep down, that when science is well done, it can lead to basic fundamental knowledge that is dependable. Now, clearly, Amazonian people have been doing something right with their approach. They’ve achieved a whole bunch of dependable knowledge about plants. You eat the wrong plant, you can die. They know which plants are poisons, which are remedies, and which are hallucinogens. They’ve even got hallucinogens for dogs. They have really a whole range of knowledge, and the plants they use are so diverse compared to what we know, and their approach has its coherence, but when you listen to them describe how they know, their systems of knowledge, they’re radically different on key points from the modern scientific approach. I thought that was interesting.

I was saying that these people we’ve looked down on for so long actually know some interesting things we don’t know, and that we need to challenge our presuppositions and arrogance. So, the book was meant as a kind of antidote, a kind of medicine.

It was clear to me from the start that there were not going to be limousines, red carpets, prizes, speeches in front of enraptured mainstream audiences for my point of view because it went against the grain. I was saying that these people we’ve looked down on for so long actually know some interesting things we don’t know, and that we need to challenge our presuppositions and arrogance. So, the book was meant as a kind of antidote, a kind of medicine. Not a bitter pill, exactly, because the whole point of doing a travelogue was to put some sugar coating on the pill, to turn it into an adventure, go to different places, meet people, listen to them. Lo and behold, they’re talking like shamans, these scientists. Isn’t that interesting?

It was designed to be a bone to be chewed on, but I was surprised by how few people actually bought it, how few people wanted to chew on it. You try to be ahead of the curve a bit, but sometimes when you’re too far ahead of the curve, people don’t get it. That’s a risk you take when you throw curve balls. Sometimes they’re not strikes.

JP: Let’s get back to the scientists for a moment. One thing you mentioned in your book is that this is actually not a new debate. You cite that Darwin, for example, in his description of ants, was really impressed by their capacity to make decisions and organize their societies, so it’s not as though there weren’t voices out there, even in the foundational moments of modern Western science who had a different view of intelligence in nature. But I asked you earlier about all the research in the last two decades that seems to confirm what you were saying about the ubiquity of intelligence in nature in your book. Do you feel that we’ve reached a tipping point?

JEREMY: That’s an interesting question. I had been working in the ‘90s in the Amazon, and then I wrote Cosmic Serpent, which led me to think more deeply about the theme of intelligence in the natural world. It seemed to me to offer a common denominator between shamanic and Western perspectives, so I thought that writing about it wouldn’t be too controversial. After all, the people I was quoting were respected scientists discussing the topic. So, I wrote Intelligence in Nature, which came out in 2005, and just that year, a few months after my book came out, the Society for Plants and Neurobiology was founded. I had in 2003 interviewed Anthony Trewavas, one of the people who was spearheading this new movement in plant biology looking at intelligent behavior in plants seriously, looking at it in terms of what goes on in the cells of a plant as it makes decisions and integrates information and so forth. But then these scientists started getting shot down by mainstream botanists, and that battle has been unfolding for the last 20 years.

The question What is a plant? looks like a simple one, but how you answer it will depend on your view of the world, whether you’re a materialist reductionist, a romantic mystic, or a shaman. That question What is a plant? is therefore almost a religious question, and, as we know, getting people from different religions to agree on something is very hard.

Since then, I’ve followed with interest the spectacle of mainstream biologists shooting at the plant neurobiology researchers, saying that it can’t be true, that plants don’t have brains and can’t have intelligence, etc. If you’re interested in looking at the presuppositions of Western culture, there is something about plants that really brings out what people believe about the world. The question What is a plant? looks like a simple one, but how you answer it will depend on your view of the world, whether you’re a materialist reductionist, a romantic mystic, or a shaman. That question What is a plant? is therefore almost a religious question, and, as we know, getting people from different religions to agree on something is very hard.

And that’s interesting because plants are the majority organisms on the planet. I think 82% of the biomass is plants. They’re the most successful organisms in the biosphere. Animals compose something like 0.4%, I think, of the biomass. Plants must be doing something right. They enable the atmosphere. They draw the sun’s energy out of the cosmos and turn it into food for all the rest of us, but modern Western cultures have had this view of plants as being totally unlike us, not intelligent, just things, objects with no agency or decision-making ability in their behaviors. But now, that’s been changing, even though there’s been resistance in science against the plant neurobiology thing, there’s just too much research to dismiss at this point. It’s been shown, for example, that certain plants start producing chemicals that poison gazelles when gazelles start eating their leaves, and then they use Jasmonic acid to communicate with other nearby plants that haven’t yet encountered gazelles, so those plants can prepare and start producing the gazelle toxin in advance. Once you include in your definition of what intentional behavior is something like producing chemical substances, then plants are behaving intentionally all the time; they’re master chemists.

Anthony Trewavas himself said that what changed it for him as a plant scientist in the 1990s was when scientific instruments and investigative processes got advanced enough to be able to intercept signals between plant cells to observe what is actually happening at the cellular level when a plant reacts to something in its environment, integrates the information and makes a decision. It turns out that the cells inside the plant are sending one another signals, some of which are identical to the ones that our own neurons send each other. And that signaling happens quickly. The old idea used to be that plants are slow. We can use timelapse photography to reveal their movements, but actually they’re very slow. And in our culture, we associate slowness with stupidity, but actually, while yes, they do operate at a time scale that is much slower than ours, the cell signals that go on inside a plant, as that plant is going about perceiving, making decisions and enacting those decisions, happen in real time at a speed similar to what happens inside our own brain, hence the birth of the field of plant neurobiology in the early 2000s.

The battle over plant intelligence goes on. Peter Minorsky recently wrote an interesting piece about the history of the plant neurobiology revolution and the resistance to it, but the fact is that even some of the scientists who have been attacked for being too “out there” conduct experiments that are methodologically impeccable. Monica Gagliano is a prime example. She is criticized because she isn’t shy about expressing her beliefs about plant intelligence and admitting her own use of psychoactive substances, but she uses reductionist, materialist, replicable, rigorous methods in her experiments. I’m a big fan of her work. Being able to prove plant decision-making and perception in a rigorous, well-designed experiment is one way knowledge advances.

When I started visiting scientists in the early 2000s, I was apprehensive at first. I had some prejudices against scientists. I thought that they would be kind of closed-minded, white coat-wearing, suspicious of an Amazonian anthropologist type, but I remember being truly surprised. I had chosen them because they were studying things that I thought were spot on, such as the butterfly visual system—What do butterflies see? How do they act on visual information? Or bees that have a capacity for abstraction and can interpret similarity and difference and handle such concepts in their sugar grain-sized brains. Or the Japanese fellow who was putting a single-celled slime mold in a maze and showing that it solved the maze. Having spoken with these men (they were all men, though at least they weren’t all Westerners), I was surprised by how open-minded they were. They were modest, epistemologically humble, aware of the limits of their knowledge, as science should be, like Darwin. You go out into the world, you explore it, you accumulate all kinds of data, then you scratch your head for years and you try to make something coherent out of it, but it starts with observing what the roots of a plant actually do, or what goes on in the brain of a bee. It doesn’t start with anything else. There is something beautiful in good, humble science, and traveling to meet these different scientists confirmed that for me.

There is something beautiful in good, humble science, and traveling to meet these different scientists confirmed that for me.

JP: Yeah, a lot of great science has really pushed the boundaries, but there is still quite a lot of resistance to any warm and cuddly feelings toward other species. We recently had Suzanne Simard at Bioneers, and she’s been getting a lot of push-back. Part of that is that many scientists work for extractive industries that are threatened by the spread of affection and respect for plants and animals. In her domain, the wood extraction industry employs many experts in silviculture, in the same way that a lot of veterinarians work for the cattle industry, so significant strata of the scientific world resist any shift in worldviews that would make their livelihood and the livelihood of their patrons more difficult.

But let’s move on to another question. It’s clear from your work and from what you’ve just said that you developed a deep respect for Amazonian Indigenous worldviews during your initial period of immersion in the region in the 80s and that you also value modern scientific approaches to acquiring knowledge. And, in fact, a lot of your life’s work has been an attempt to compare and to reconcile these two very different pathways to obtaining knowledge. I’ll put my cards on the table here. I too have deep respect for both these traditions, but they seem to me to be coming from such divergent perspectives that I’m not convinced they can really ever be fully reconciled. But, as you say, the scientists you interviewed were speaking more like shamans, so do you feel that your effort to try to reconcile these two ways of knowing is progressing, getting closer to a possible resolution of some kind, or do you think that these two such different methodological strategies will remain irreconcilable for the foreseeable future?

JEREMY: I don’t think that they’re irreconcilable. Once you take everybody’s costumes off and you just look at what individual scientists know and how they arrive at what they know, and at what Amazonian shamans might say about the same kinds of questions, it’s at its core not that different. They all see plants and animals and want to know how they work. Some plants can be remedies. How do we use them to heal people? What does healing actually mean? They’re all interested in trying to heal people and in plants that might help people heal, and they’re all interested in understanding the properties of plants. We do live on the same planet, after all. We’re part of the same species.

Once you take everybody’s costumes off and you just look at what individual scientists know and how they arrive at what they know, and at what Amazonian shamans might say about the same kinds of questions, it’s at its core not that different.

But, yes, we have different approaches to knowledge. It’s kind of like two languages that require translating to become comprehensible to each other. In Italian, they say “Il traduttore è un traditore”—the translator is a traitor, because anytime you say something in one language, to actually say it with the same kind of feeling and true content in another, you often have to change the terms, and their order. If you just translate it directly, you’ll be losing meaning. A good translator is going to deconstruct it and betray the original, but reconstruct it into something that actually in that context is the best solution and comes closest to doing the job. So, there’s not always an exact correspondence of concepts, but you can go back and forth between radically different languages and do decent translating.

And once you put something in French, it’s no longer in English. That’s true. Once you look at it from a shaman’s point of view, you are no longer looking at it from a scientist’s point of view, and there are some things that are to a certain extent incommensurable. They don’t fit into each other; they don’t have the same terms. One thing that’s really striking is that often in science, individuals, including myself, are interested in universals. We don’t just study one river, we study rivers, river systems, but when you go to a place where Indigenous people live by a river, they’re relatively uninterested in rivers, but they know a lot about their river. They love their river. They have stories about their river. They may have some knowledge about other rivers, but they just don’t approach the whole thing in that way.

Another example I like is an episode that a Brazilian neuroscientist told me about. Two or three years ago some brain scientists from the Czech Republic got interested in ayahuasca states and decided that they really wanted to do electroencephalogram readings in the rainforest with Indigenous shamans while they were singing their songs in their own settings. This had to be participatory research, so they had to get the people they wanted to work with, the Huni Kuin Kaxinawá people, on board. They went to Acre to meet them. They explained that they had this new machine that could do these measurements and withstand the humidity of the tropical forest, but the Kaxinawá said: “What’s all this preoccupation with the brain? When we hunt animals, the brain is the only thing we don’t eat, the only part of the body that is without interest. And here you are, showing up, and all you want to do is measure activity in the brain. Why?” That’s a great illustration of Indigenous people and scientists approaching the same elephant but not necessarily at the same level and with the same interest, and not touching the same bits of the animal.

But that’s why I don’t think the two approaches are irreconcilable: it’s still the same animal. We’re living on the same planet. Everybody wants to understand more about plants, animals, what it means to be alive, how to avoid illness, and so on. So, yes, scientists are hard for Indigenous Amazonians to understand sometimes, and vice versa, because they speak different philosophical languages, but I think it’s possible and interesting to become bilingual. One metaphor is that the Amazonian perspective can offer a sort of reverse camera angle. In a televised sporting event, you have the main camera angle, and then when you have a reverse angle, you can see the same action but from the other side of the field. The reverse angle can show you things that the main angle doesn’t, so, being able to go back and forth and say, okay, let’s see how the other side would see this, can offer you new insights. Another metaphor is to think of them as different maps of the same territory that you can superimpose to get a more complete understanding.

Knowledge is knowledge. If it’s dependable, then it’s knowledge. Indigenous people have developed dependable knowledge, and scientists have done the same.

And finally, that’s what we’re after—knowledge is knowledge. If it’s dependable, then it’s knowledge. Indigenous people have developed dependable knowledge, and scientists have done the same. So there’s no reason, given that they peddle in the same thing, that they shouldn’t be able to do this together. I argue against the irreconcilability of these two ways of knowing.

JP: There are two other topic areas I’d like to cover. The subtitle of your book is “an inquiry into knowledge,” and in the book, you talk about the brain quite a lot. You have a whole chapter on the pile of jelly that is the brain. You really wrestle with the hard question of consciousness and discuss how little we know about how our cognition works or how we arrive at our sense of a self. Your conclusion in the book is that we’re really at the infancy of coming close to understanding that, but do you think that that’s something that might ultimately be unknowable, no matter how many brain studies we do?

JEREMY: I know that I’m far from the first to point out that the subject that we’re dealing with in this question is the same that is trying to come up with the answer, and that is, I think, obviously part of why this may well be out of reach for quite some time. In other words, can the human mind understand the human mind?

Well, there’s no reason why it should be able to understand itself. If you look at it, it has evolved mainly to understand everything except itself. There we are. We’re on this planet. We’ve got to survive, avoid being eaten by mega fauna, find food for tonight. For tens of thousands of years, we’ve been paying attention to everything around us, but certainly not what’s in between our two eyes, but now science has reached that point at which it can turn its attention to the human brain, human consciousness. Here is this kilo-and-a-half of jelly. How does conscious experience spring out of it? Well, that’s the famous hard question of consciousness studies.

I’d feel completely at ease with the idea that it’s going to take tens of thousands of years to get anywhere close to getting a good understanding of how our conscious experience springs out of that mass of jelly inside our skulls.

I’d feel completely at ease with the idea that it’s going to take tens of thousands of years to get anywhere close to getting a good understanding of how our conscious experience springs out of that mass of jelly inside our skulls. But, hey, if somebody’s going to deliver the explanation in the next 50 years, I’d be pleased to eat humble pie.

JP: Yeah. I always felt that it’s akin to the problem of understanding death. One is trying to understand absence of consciousness with consciousness. It seems to me to be the wrong tool for the job. But another question I have is about your cultural influence. You were really one of the most influential figures in getting a lot of people interested in Amazonian shamanism and in the larger psychedelic revival that came about starting in the ‘90s. After the explosion of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, things went more underground, and when they exploded again, The Cosmic Serpent helped inspire quite a few people to want to explore these things. I was wondering how you feel about what’s happened to that domain in the interim, because that explosion of interest in psychoactive plants and psychedelics in general has led to a number of epi-phenomena, everything from parts of the Amazon being overrun by spiritual tourists, similar to India in the ‘70s, to venture capitalists rushing to cash in, to weird belief systems spreading in the psychedelic world. Conspiracy theories of all kinds have been rampant in some of those milieus, including some emanating from the far right. How do you feel about the whole world of psychedelics now, and do you have any second thoughts about your participation in having contributed to popularizing sacred plant use?

JEREMY: I’m a long way from feeling responsibility. First of all, when I wrote the book and published it in 1995 (the original French edition of The Cosmic Serpent), I would never have thought that people would say: “Where can I get some of that stuff that makes you vomit and see terrifying fluorescent serpents?” Westerners, at that point, were eating Ecstasy, maybe taking small doses of LSD to go to the discotheque. They were not interested in gut-wrenching purges and serpentine visions.

But, to my surprise, when I gave my first talks after publishing the book, people would come up to me afterwards and they’d ask where they could get some. It was as if I’d been talking about some interesting drug or something, and they really felt that they needed it. I realized afterwards that in the 1990s, a saturation point seemed to have been reached by a lot of Western people, a minority certainly, but still a noisy one, were questioning Western culture and Western medicine. Quite a few of them were ready to leave their culture to go and suffer, to go and purge, to go on a kind of pilgrimage. This is how ayahuasca tourists have been described by anthropologists—pilgrims searching for knowledge, searching for self-healing by going to distant cultures and suffering. Around the same time, other pilgrimages were becoming immensely popular, such as the St. Jacques de Compostelle/Camino de Santiago trail.

So, in the 1990s, more and more Westerners had begun questioning their consumerist culture, allopathic medicine, and monotheistic religion, looking for other approaches to healing. Ayahuasca was part of that. I got lucky for once: the book was right where the curve was. It was a sweet spot. Lots of people read it. I didn’t have to do any publicity; it sold itself. It’s still selling, because it tapped into something that just happened to emerge at the point where the book was there. But did the book cause that interest? I doubt it, and, in any case, you don’t control your readers. I always put an emphasis on verifying knowledge, giving sources, showing that it’s complicated, but there will always be some readers (of anything) who go overboard. Many years ago, a woman called me up, all upset because her husband had read my book and started taking mushrooms, and then he was taking mushrooms all the time and going everywhere with my book and reading bits of my book to people he didn’t even know, i.e., going crazy. But what are you going to do? I certainly didn’t want that to happen. Still, despite such isolated cases, 99% of the people who read the book actually got the message without losing their minds.

As to the Westerners who have become ayahuasca-guzzling, conspiracy-theory minded types who are also into white supremacy or what have you, this is where science should be taken into consideration. The word psychedelic means “revealer of psyche.” Stan Grof, the Czech psychiatrist who invented psychedelic psychotherapy back in the 1950s said when you take a psychedelic such as LSD (and this applies to ayahuasca as well) you don’t really have an experience of a drug, you have an experience of yourself. It takes the lid off ordinary consciousness, and all kinds of things in the deep human psyche come out, so it really depends on who you are when you take one of these things. As Stan Grof put it, they’re “non-specific amplifiers.”

If you’re an ambitious, aggressive, patriarchal kind of person, if you take ayahuasca, there is a good chance it’s going to make it worse. They’re well aware of this in the Amazon. There’s a lot of sorcery associated with psychoactive plant use there. Using those plants can be a form of knowledge acquisition, and knowledge can confer power, which is inevitably double-edged, so you’ve got to pay attention. But that’s also true of scientific knowledge. I’m all in favor of knowledge, be it scientific or shamanic, but when certain forms of knowledge get into the wrong hands, it can be used negatively and destructively.

I’ve always tried to accompany my discussions of knowledge and how one knows things with discussions of meaning, respect for other species, respect for other cultures, respect for scientists, respect for shamans. I try not to put anybody down in my books. It’s true that there have been all kinds of deplorable things done in the shamanic, psychedelic and scientific worlds, but I don’t try to tell people what to do. For one thing, you can’t really because they won’t listen. So, yes, depending on who reads the book and who drinks ayahuasca, all kinds of things can happen, but in the rare instances where people have gone off the deep end after reading my book, I have not felt that the problem came from anything I wrote or suggested. But I’m open to discussion about the subject, if only because I think that words matter, especially my own.

So, I must believe, if I believe anything, that increased knowledge about the natural world will be for the better…and more research is needed. That’s always the concluding sentence.

JP: It’s interesting that the marine biologists and their associates working on decoding whale communication using artificial intelligence are very focused on the ethics of it. If we discover a way to communicate effectively with these animals, what is our responsibility? The U.S. and Soviet research decades ago to attempt to use dolphins as weapons and spies reminds us that there’s often a dark side to knowledge, even if it’s about intelligence in nature…Science doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it’s part of a social order rooted in the accumulation of power and wealth by small minorities.

JEREMY: Where I dispute that is that once people start looking at plants and other animals as intelligent beings, I think 98% of them feel greater respect for the world around them. Once you open up to the intelligence of a dolphin or a blade of grass or an ecosystem, I think that most of the time, the understanding that comes from that opening is going to increase tolerance and lead to a better understanding of our place in the biosphere. When you consider how little we know about plants, what motivates them, what their perspectives are, and knowing that the world we live in is this very vegetal world, we have a lot of room for improvement when it comes to acquiring basic knowledge about the world around us. So, I must believe, if I believe anything, that increased knowledge about the natural world will be for the better…and more research is needed. That’s always the concluding sentence.