The Surprising Way Monkeys Responded to Hurricane Maria—and What It Might Say About Us

Bioneers | Published: May 19, 2025 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

Cayo Santiago, a 38-acre island off the coast of Puerto Rico, may be uninhabited by humans, but it’s far from empty. The island is home to a colony of approximately 1,700 rhesus macaque monkeys. The monkeys, which were first brought to the island from India in 1938, are the world’s oldest continuously studied group of free-ranging macaques. For researcher Lauren Brent, the island represented an ideal location to study the behavior of these highly social primates.

In “The Well-Connected Animal: Social Networks and the Wondrous Complexity of Animal Societies,” evolutionary biologist Lee Alan Dugatkin writes that by 2017, Brent and her colleagues at the lab of neuroscientist Michael Platt had a deep understanding of the way that the social networks of macaques on the island worked and what they meant. Then Hurricane Maria struck, hitting the island with its full force and devastating everything in its path. The scientists feared the worst for the macaques.

“They weren’t all dead, but Hurricane Maria turned the monkeys’ world upside down and meant they needed to reestablish their society, with all its intricate and complex working parts. And quickly,” Dugatkin writes. “For Brent and her team, Hurricane Maria meant many things, including figuring out new ways to think about the effects of large-scale natural disasters on social networks.”

How would fewer resources, including reduced food and shade, affect the monkeys’ dynamics? In the following excerpt from “The Well-Connected Animal,” Dugatkin tells of the distinct shifts in the macaques’ social behavior following the Category 4 Hurricane that decimated their world.

Lee Alan Dugatkin is an evolutionary biologist and historian of science in the Department of Biology at the University of Louisville. In addition to “The Well-Connected Animal,” he is coauthor of “How to Tame a Fox (and Build a Dog)” and the author of “Power in the Wild,” both also published by the University of Chicago Press.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from “The Well-Connected Animal: Social Networks and the Wondrous Complexity of Animal Societies” by Lee Alan Dugatkin, published by University of Chicago Press, 2024.

More than 60% of the green vegetation on Cayo Santiago, along with a lot of the infrastructure that the Cayo team had put in place—including the feeders that supplied the animals with some of their food, which they now needed more than ever—was decimated by Hurricane Maria. But not a single macaque was killed during the hurricane, and only about 2% of the animals died shortly thereafter, probably due to starvation. “It’s completely incredible,” Lauren Brent says. “They’re not that big, right? And all their trees were being blown over. It’s not like you can hold on to something.” At first Brent thought that maybe the macaques hid in a place known as Happy Valley, which is partially protected from wind, but normally Happy Valley holds fifty macaques, and there was no way it could have provided shelter for 1,700 monkeys. She and her team are working hard to piece together what happened, but still have not been able to figure out how every single macaque survived the full brunt of a Category 4 hurricane.

About three months after Maria, when the shock had partly worn off, Brent began thinking seriously again about the dynamics of macaque social networks, primarily because of what she was hearing from Danny Phillips and the other field assistants who were back on the island. They’d tell her “the monkeys are acting weird,” and when Brent would ask how so, the on-the-ground team told her that they seemed to be especially friendly toward one another. In early 2018, about five months after the hurricane, she went down to check for herself. The island was still reeling from Maria (as was most of Puerto Rico). “But when I got to Cayo,” Brent says, “I was like ‘Yeah, I see it.’ . . . They look more tolerant. . . . Monkeys I never expected to be cool just sitting next to each other.’ ”

They’d tell her ‘the monkeys are acting weird,’ and when Brent would ask how so, the on-the-ground team told her that they seemed to be especially friendly toward one another.

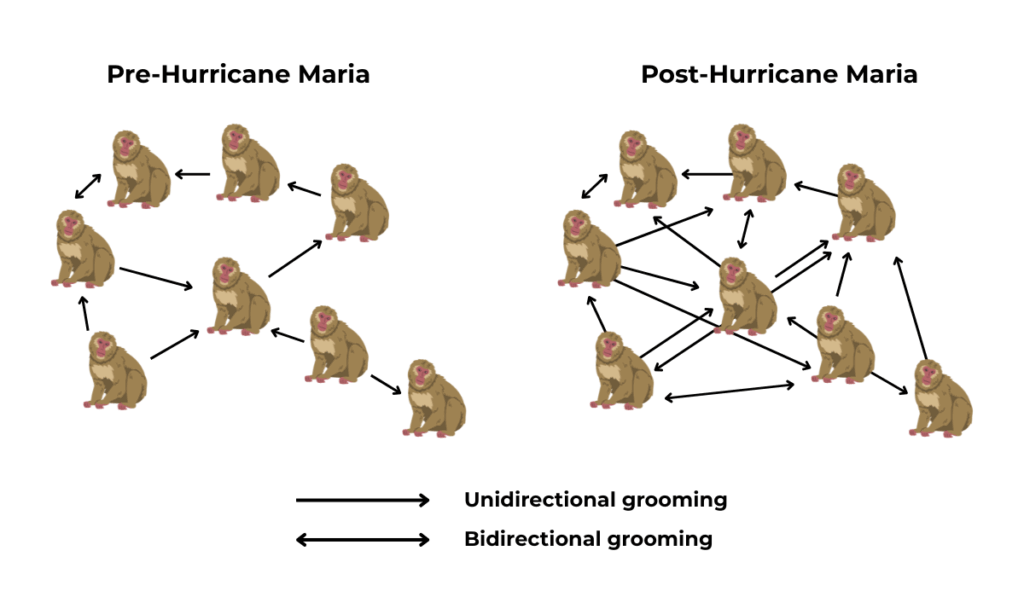

At the time, very little was known about how animals adjusted their social dynamics after full-scale natural catastrophes, and as awful as the consequences of Hurricane Maria were for Puerto Rico, perhaps, Brent thought, one silver lining might be that the disaster shed light on those dynamics. When she and her team looked more deeply at her suddenly much more friendly macaques, what they found was that Maria had fundamentally altered the social networks of the monkeys. For one thing, when they compared the grooming and proximity networks in two groups of macaques during the three years prior to Maria versus the one year immediately after the hurricane, the data confirmed the anecdotal observations about the monkeys being nicer to each other: macaques were four times as likely to be found close to one another after the hurricane, and they were 50% more likely to groom one another. What’s more, monkeys who groomed least and had spent the least time near others before Maria were the ones who showed the greatest increase in these behaviors after the hurricane.

Focusing their analysis on grooming behavior, Brent and her colleagues thought that the changes in network structure might be due to either an increase in the number of partners or an increase in time spent with specific partners. Or perhaps a bit of each.

What they found was that post-Maria, macaques had more social partners, but the average strength of a grooming relationship with a partner had not changed. The monkeys had formed more friendships in their network, not strengthened already existing ones: Maria had brought the macaques in a group closer together, with additional grooming partners buffering them from the devastating effects that the hurricane left in its trail. And again, friends of friends mattered: monkeys took the path of least resistance in forming new relationships. If monkey 1 had been in a grooming relationship with monkey 2 before Maria, it was more likely to enter a grooming relationship with one of monkey 2’s grooming partners after the storm. Disaster, in the form of Maria, had brought the monkeys closer to one another, and social network analysis was the perfect means to show how.