When the Salmon Died: A Family’s Fight to Restore the Klamath River

Bioneers | Published: October 28, 2025 Indigeneity Article

For more than a century, the Klamath River has been at the heart of one of North America’s most significant environmental justice movements. Beginning in the early 1900s, a series of hydroelectric dams cut off salmon migration routes, destroyed fisheries, and devastated the livelihoods and cultural practices of the Yurok, Karuk, Klamath, and Shasta Nations.

In 2002, a massive fish kill on the Lower Klamath caused by low flows, high temperatures, and disease became a turning point. For Tribal communities, it was a moment of both unbearable grief and renewed resolve.

That resolve has carried through generations and is now transforming the river itself. The largest dam removal project in U.S. history began in 2023. The river now runs freely for the first time in over a century, signaling a new era of ecological and cultural revitalization led by the region’s Tribal Nations.

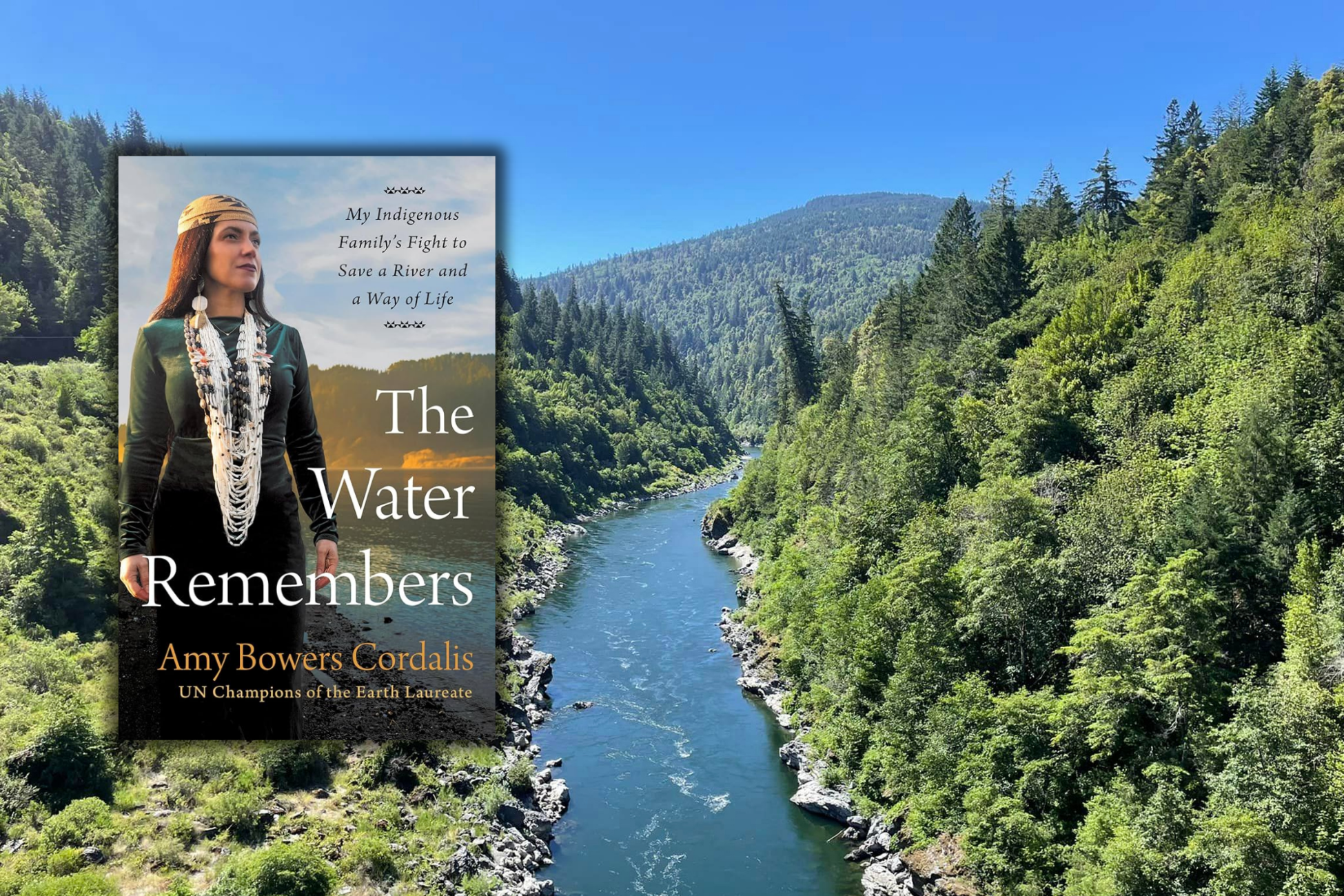

Amy Bowers Cordalis, a Yurok attorney and former General Counsel for the Yurok Tribe, has been at the center of this fight. In her new book, The Water Remembers, she tells the story of her family’s 170-year struggle for justice on the Klamath — from her great-grandmother’s resistance during the Salmon Wars to her own role in securing the river’s restoration.

The following excerpt takes us back to the moment when that fight became deeply personal: the day Cordalis and her family discovered thousands of salmon dying in the river. It’s a heartbreaking scene, but what followed is a story of reclamation, resilience, and the enduring power of Indigenous leadership to heal a river and a people.

(Watch Amy Bowers Cordalis’ Bioneers keynote about the restoration of the Klamath River.)

Enter our giveaway for your chance to win a free copy of The Water Remembers!

“It smells like death,” Mike said, “some kind of organic decomposing. I don’t smell or see any chemicals, so it’s not a chemical spill. It seems to be only salmon dying.” There were no smaller fish, like trout, or larger fish, like sturgeon, dead. On the banks, the birds still flew and there were no visible dead animals. Only the salmon were dying.

“Should we pick the salmon up?” Merle asked, peering down into the electric-green water.

“How we gonna pick them up?” I asked incredulously. “Their gills and bellies are rotting, and the water looks toxic.”

The fish next to the boat were dead, their mouths clenched open and eyes clouded over. The sides of their bellies were wounded, the skin brown, red, and gray where it appeared to have burned and then rotted. My stomach turned, followed by my heart. Their gills were not their usually bright pink and instead were light gray with white spots. I was paralyzed and in shock by the sight. I felt extreme panic, devastation, and confusion. These were the fierce River beasts that I had battled for me and my family’s survival. I knew them as aggressive fighters who could break human bones with a whack of their tail or move their bodies back and forth to jump out of fishing boats. Now, they had succumbed to something so powerful it killed them en masse. What had killed them? How could we stop it?

Mike broke me out of my stupor. “This is serious, guys. Let’s go up the River. There are probably more.”

We turned a bend in the River near the glen. Merle pointed up the River.

“What is that? Do you see it?” He gunned the boat toward an eddy, where the water pulled in a circle and then shot out whatever it caught onto the riverbank. After which a five-hundred-foot straight stretch of River came into view.

“Oh my god,” I murmured as we got closer.

“Stop the boat, Merle,” Mike said somberly.

Before us, for the next half mile, were hundreds of dead salmon in the water and on the riverbank. Large salmon. Some were floating down the surface of the River and others got caught in the eddy, circling eerily. More had been pushed out of the eddy and were beginning to pile in layers along the riverbank, three to four salmon deep, their bodies distorted and tortured. Just like the first dead salmon we saw, here the salmon’s gills, rotted and gray, swelled out from their heads. They were white and filled with small white dots, tiny organisms that had sucked out the blood and oxygen that would have normally flowed through a healthy gill. Their bellies had exploded from the inside out, like they had swallowed a bomb. Blood and guts poured into the River. What skin remained intact was a dark red, a stark contrast to its normal silvery chrome color, and gray from rotting. The water where the salmon pooled was covered with a bubbling film, toxic blue-green algae, and a gray sludge that moved with the carcasses.

We stood in the boat staring, slowly moving upriver. There were so many dead salmon in the water. We didn’t want to run them over, but it was almost impossible not to. All three of us were silent, in shock. “No one touch anything,” Mike finally said. “This looks like ich, a fish disease. But in case it’s something else, don’t touch the fish.” “This is a massive fish kill. I don’t know how else to describe it,” Merle replied, staring out into the water. “What is going on? How did this happen?” “Why are they dying?”

“How do we stop it?”

We fumbled for words as our minds raced through a series of unspoken questions and fear of what could happen next. Nothing like this had ever happened before. I thought of all the fish stories and Yurok myths my family had told me. None of it made any sense.

This River was made for salmon. It was September, when the salmon migrated up the River. How could the salmon be dying here?

“There has to be a biological explanation for this,” Mike reasoned. “Some ecological reason. It’s a drought year. The water has been low for a while, and it got lower recently. It’s been hot, much hotter than normal.” “We’ve been catching a lot of fish over the last few days,” Merle noted. “We have a big allocation this year. It must be a big run. I think the bulk of the run is in the River now.”

“The water is so low it has been moving slow, almost stagnant. The water is hot too,” I said.

“The flows at Iron Gate went down 41 percent to six hundred cubic feet per second two days ago. The bureau probably cut the water flows to the River to give more water to the farmers. The US Vice President was in Klamath Falls two weeks ago to visit the farmers,” Mike said. “They must have reached a deal. They must have diverted the water. That would explain the low flows.”

We started the boat back up and continued up the River. The size of the fish kill grew as we traveled. Just fifty yards ahead, in another eddy, the same scene: hundreds of salmon dead, their bodies mutilated. The farther we traveled, the more salmon we saw lining the banks of the River. The sun was baking them, turning rotting fish into rotten corpses. The smell was so concentrated and potent, I gagged. “Here, put this over your nose,” Merle said, handing me a cloth. “Merle, let’s stop at my dad’s camp at Brooks Riffle and see if it’s the same there.” “Sure,” Merle said.

As we pulled around the last River corner before Brooks Rif- fle, two to three layers of dead fish lined the banks of the River for a five-hundred-yard stretch. They lay there mangled, battered, and bruised like a line of dead soldiers waiting to be buried. Yet the redwoods, alder, and willow trees all continued to stand tall. The mountains and the ridges towering over the River stood still. The birds still flew by overhead. The water still rolled toward the ocean, but it moved at a lethargic pace, quiet and solemn, as if in mourning.

If water has memory, it would remember this day. It would remember growing hotter, holding those salmon as they died, as they gasped for air, as the fish disease sucked the oxygen from the salmon and killed them. It would remember how it had failed the salmon, unable to provide them with sanctuary.

This excerpt is posted with permission from The Water Remembers by Amy Bowers Cordalis, published by Little Brown and Company, October 2025.