What Neuroscience Reveals About Animal Minds

Bioneers | Published: January 28, 2026 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

When Gregory Berns joins our call, he isn’t sitting in a lab or a lecture hall. He’s calling from his farm in rural Georgia, and he’s in the middle of a fight against the rapid expansion of massive data centers spreading across the landscape south of Atlanta. Developers are proposing facilities millions of square feet in size, drawn to poorer counties where land is cheap and tax revenue is desperately needed. Once built, the land is permanently altered.

For Berns, a neuroscientist known for putting awake, unrestrained dogs into MRI scanners, the fight against data center sprawl isn’t separate from his research. It’s another expression of the same problem he’s been circling for years: what happens when complex lives — human or nonhuman — are flattened into abstractions, and when systems are designed to ignore what they consume.

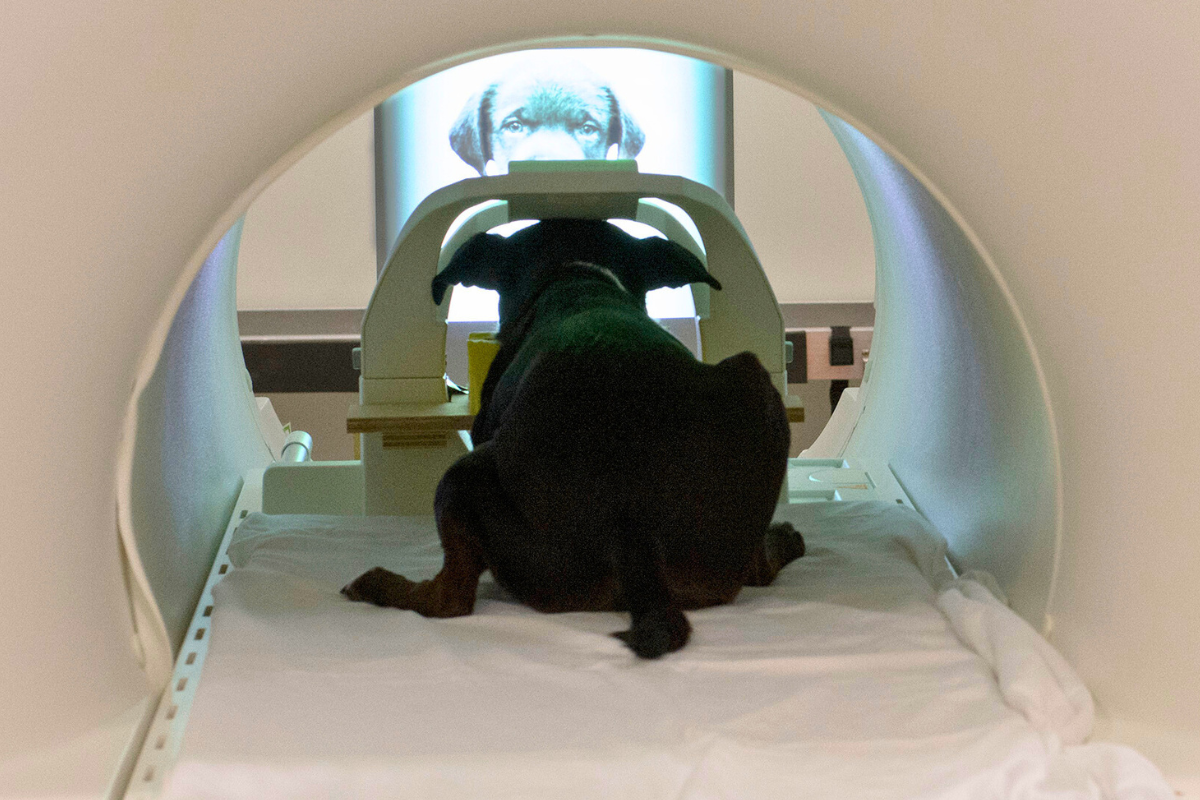

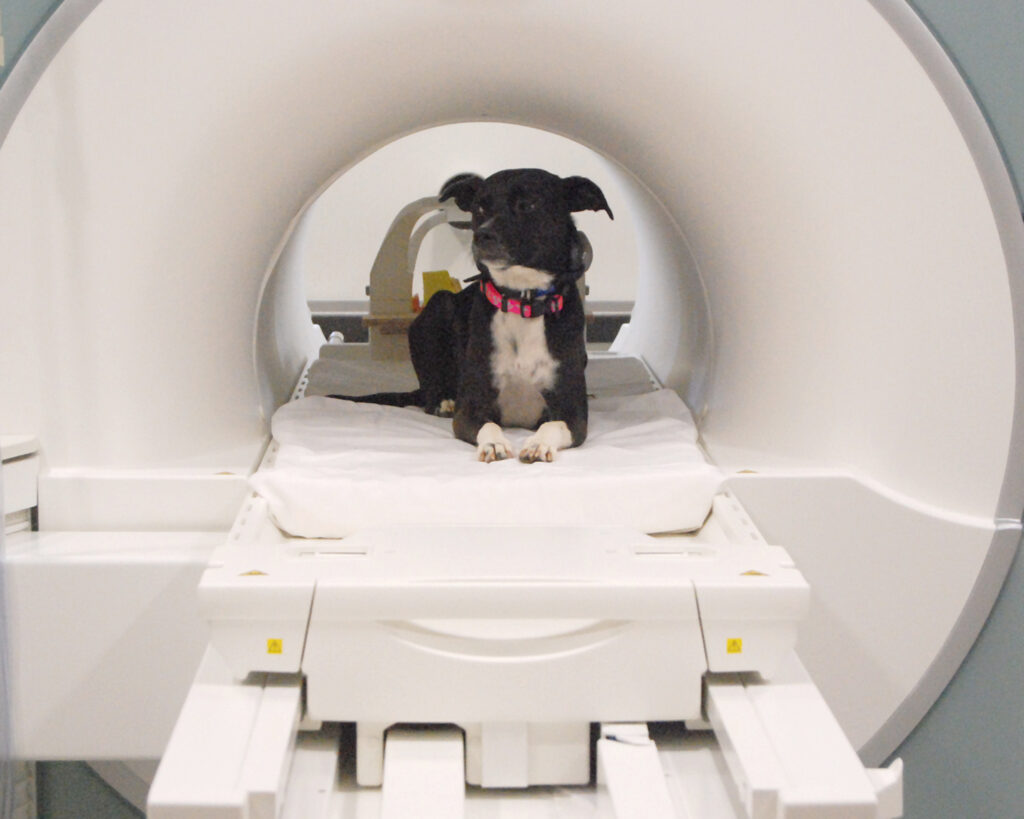

Now a Distinguished Professor of Neuroeconomics at Emory University, Berns spent decades studying human decision-making using functional MRI before turning his attention to animals. Around 2011, that curiosity narrowed in on dogs — one of the few nonhuman animals able to cooperate with brain imaging without anesthesia or restraint. What began, as he puts it, as “an idea in search of a question” quickly opened into something much larger. Why stop with dogs? There are roughly 6,000 mammal species on the planet, yet humans have meaningfully studied the inner lives of only a handful.

Today, Berns’ work is driven by a deceptively simple aim: to better understand the interior worlds of other mammals, without harming them, and with animals treated as partners rather than passive subjects. Using noninvasive brain imaging, he explores what behavior alone can’t reveal — how animals perceive, decide, feel, and relate — and what those discoveries mean for the ethical systems humans have built around them.

In the conversation that follows, Berns reflects on what neuroscience can and can’t tell us about animal minds, why individuality is such a disruptive concept in how we treat other species, and how acknowledging animal inner lives challenges the assumptions that underpin everything.

You can read an excerpt from Gregory Berns book Cowpuppy here.

Bioneers: In nonhuman animals, what does brain imaging offer that behavioral observation can’t?

Gregory Berns: For much of the 20th century and even into the 21st, the only way to try to understand what was going on in another animal’s mind was to study behavior. You observe what an animal does and try to infer what’s happening internally. That’s how behaviorism and operant conditioning really took hold, based on the idea that animals learn through simple rules of reward and punishment — carrots and sticks.

But that turns out to be a very incomplete picture. Even with humans, we know we’re not strictly governed by rewards and punishments, and animals aren’t either. There’s ample evidence that many animals build internal models of the world: mental representations of their environment and the other beings in it. They make decisions based on those models. That’s a much more efficient way of navigating the world than constant trial-and-error. Animals are far more efficient than that.

Brain imaging offers a different way in. If an animal can sit still in an MRI scanner, we can start to see circuits in action — not individual neurons, but large-scale patterns of activity related to motivation, perception, and decision-making. And because mammal brains are so similar in their basic structure, we can link what we see in other animals back to what we already know about humans, and cautiously infer what another animal might be experiencing.

A good example of why that matters is jealousy. Most dog owners will tell you their dogs experience jealousy, but for a long time many scientists would say it’s too complex an emotion to attribute to animals.

We designed an experiment to explore that question. Dogs were in the MRI scanner, looking at what appeared to be another dog — a very realistic dog statue — with their owner positioned in between. Sometimes the owner gave the dog in the scanner a treat. Other times, the owner turned and gave the treat to the fake dog. As a control, we also used a bucket, so in both cases the dog wasn’t getting the food, but only in one case was it going to something that looked like another dog.

In some dogs, that situation evoked activity in the amygdala, a brain region associated with arousal and emotional reactivity. And importantly, that response correlated with dogs who had a history of aggression.

The key point is this: The dogs were extremely well trained. They stayed perfectly still in the scanner. Behaviorally, they were doing exactly what we wanted them to do. But beneath the surface, it was bothering them, and that’s something you would never know just by watching the dog. It shows the real limitation of relying on behavior alone to understand what an animal is experiencing internally.

Bioneers: So in brain scans, if the same area lights up in dogs and humans, what can we actually conclude from that?

Gregory: That’s what’s known as reverse inference, and it’s something people in brain imaging argue about a lot. The basic idea is that if you see activity in a particular brain region in an animal, and that region looks structurally and functionally similar to the same region in humans, you can make a cautious inference about what the animal might be experiencing.

But it’s not a certainty. Even within humans, our interpretations change over time. I spent many years studying what we used to casually call the “reward system.” For a long time, when we saw activity in those dopamine-related circuits, the knee-jerk conclusion was that the person was experiencing pleasure. We now understand that’s too simplistic. Those circuits are more about motivation — about something being salient or worth paying attention to — and whether that motivation is positive or negative depends heavily on context.

So when we see similar patterns in dogs, we’re making the same kind of inference, but carefully. You need more context to know whether something is pleasurable, aversive, or something else entirely.

Bioneers: When has your own intuition about dogs not matched what you found in their brains?

Gregory: One clear example came from some of the last experiments we did, where we created movies specifically for dogs to watch in the scanner. We filmed everything from the dog’s point of view — using GoPros, walking around dog parks, showing scenes we assumed dogs would find interesting.

My intuition, very much shaped by being human, was that dogs would be focused on who was on the screen. Is that a dog? Is that a person? Is that someone familiar? But when we analyzed the brain data using machine-learning methods, that’s not what we found.

What the dogs’ brains were really distinguishing was what was happening, not who was doing it. They could clearly differentiate between actions like walking versus eating, but they didn’t strongly discriminate between whether it was a dog or a human performing those actions. It wasn’t who was on the screen; it was what was happening.

That was a good reminder that we’re always at risk of projecting our own way of seeing the world onto other species. I’m human, and I interpret scenes in a very human way. But dogs evolved to pay attention to different kinds of information, and brain imaging can reveal those differences in ways our intuition often can’t.

Bioneers: Affection is something many people feel instinctively in their relationships with animals, especially dogs. How did you translate that intuition into something neuroscience could actually test?

Gregory: Affection was one of the early questions I really wanted to answer, because it’s something dog owners feel very strongly about. We designed an experiment that was essentially Pavlovian. The dogs learned that one signal meant they were going to get a food reward, and another signal meant they were going to get praised by their owner. Then we looked at what happened in their reward-related brain circuits.

What we found was that for about 75% of the dogs, there was equal activation in those circuits when they anticipated food and when they anticipated praise from their owner. To me, that’s about as close to proof as you can get that dogs experience genuinely positive feelings toward their people and that those feelings aren’t purely transactional. I’m happy to call it love.

What’s been even more striking to me, honestly, is my experience with cows. Once I got to know them and they accepted me into their herd, they began offering affection in the same way they offer it to each other: licking, staying close, engaging socially. I can give them treats, but for the most part, that’s not what drives the relationship. It’s not like a dog showing up because it thinks there’s food involved.

In many ways, that makes it feel even more genuine. It reinforces the idea that rich emotional lives, including affection, aren’t limited to the animals we’re most comfortable loving.

Bioneers: Your research shows that individual animals’ brains — even within the same species — can be remarkably different. Why is individuality such a disruptive idea when it comes to how we treat animals?

Gregory: Over the course of my career, I’ve probably scanned around a thousand human brains. And what you see very quickly is that everyone’s brain looks different; it’s like a fingerprint. Even when people are doing the exact same task, the patterns of activity vary from person to person. They’re stable within an individual, but across individuals, they’re remarkably diverse.

When we started scanning dogs, it was the same story. Early on, my students would get discouraged because the data looked so messy. I’d tell them, “Don’t analyze it yet. You need enough subjects to see the pattern.” But the reason it feels messy is that dogs are individuals. Their brains vary just as much as human brains do.

We even saw this in a large study we did with Canine Companions for Independence, where we scanned puppies being trained as service dogs. These dogs were incredibly similar on paper — mostly golden retriever–lab crosses, raised and trained in nearly identical conditions. Even then, their brains all looked different.

Individuality is subversive because it doesn’t fit neatly into systems designed for efficiency. Industrial agriculture, in particular, depends on flattening animals into categories: “cattle” rather than individuals. Once you start thinking about animals as distinct beings with their own inner lives, the whole system becomes harder to justify. You’re less likely to eat something with a name, which is why ranchers traditionally don’t name their cows.

Recognizing individuality forces us to confront the moral shortcuts we’ve built into the way we treat other animals, and that’s deeply uncomfortable for a lot of people.

Bioneers: If we truly accepted that animals have rich emotional lives, what would have to change in our idea of “normal” life?

Gregory: I think, at some level, most people already accept that animals have emotional lives. You’d have to be pretty hard-hearted to deny that. Even the ranchers and cattlemen I know aren’t blind to it, they just wall it off. Compartmentalization is the real issue.

The bigger crisis goes far beyond food. It’s about wild mammals and the sheer amount of space they need to survive. Many species, especially large mammals, require vast, connected habitats. What we’ve done instead is parcel land into smaller and smaller pieces, cut it up with roads, and turn ecosystems into isolated islands. Once animals can’t move where they need to go to find food, mates, or seasonal refuge, extinction becomes almost inevitable.

Urbanization has made this harder to see. About 80 percent of people in the U.S. now live in urban areas, which is a complete reversal from a century ago. Most people are physically and psychologically distant from the consequences of development. Living on a farm has made those connections impossible for me to ignore. You see immediately how one change affects everything else that lives there.

I’m not especially hopeful that this will change quickly. But education matters. Organizations like Bioneers can help bridge that gap by reminding people that we share the planet with these other species — and that the choices we normalize have consequences far beyond our own lives.