Deep Listening: Whale Culture, Interspecies Communication, and Knowing Your Place

Bioneers | Published: September 25, 2023 Nature, Culture and SpiritRestoring Ecosystems Podcasts

Dr. Shane Gero, a visionary marine biologist, is angling to crack the code of sperm whale communication. His mind-bending research is transforming what we thought we knew about these ancient leviathans. It’s calling on us to embrace the reality that perhaps we’ve long suspected: Sperm whales are living meaningful, intelligent and complex lives whose cultures suggest that whales are people too. What can whale culture teach us, and can deep listening help us learn to coexist respectfully in kinship with these guardians of the deep?

Featuring

Shane Gero, Ph.D., is a Canadian whale biologist, Scientist-in-Residence at Ottawa’s Carleton University, and a National Geographic Explorer. He is the founder of The Dominica Sperm Whale Project and the Biology Lead for Project CETI. His science appears in numerous magazines, books, and television; and most recently was the basis for the Emmy Award winning series, Secrets of the Whales. Learn more at shanegero.com.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Teo Grossman and Kenny Ausubel

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

- Special Engineering Support: Eddie Haehl at KZYX

This is an episode of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature series. Visit the radio and podcast homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station and how to subscribe to the podcast.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

Neil Harvey (Host): In this program, we meet Dr. Shane Gero, a visionary marine biologist who is angling to crack the code of sperm whale communication. His mind-bending research is transforming what we thought we knew about these ancient leviathans. It’s calling on us to embrace the reality that perhaps we’ve long suspected: Sperm whales are living meaningful, intelligent and complex lives whose cultures suggest that whales are people too. What can whale culture teach us, and can deep listening help us learn to coexist respectfully in kinship with these guardians of the deep?

I’m Neil Harvey. This is “Deep Listening: Whale Culture, Interspecies Communication, and Knowing Your Place” with Shane Gero…

Shane Gero (SG): Human cultures have played a huge part of deciding where people live and how they behave across human civilization. As early humans evolved, language served as this cheat sheet for ‘do you do things the same way I do?’ And even today, you’re far more likely to help someone who yells for help in your natal language than in any other. And so culture can be this unifying force, but also, of course, a very divisive one, and it’s structured all of human civilization.

Host: Dr. Shane Gero has spent the past two decades studying whale culture. Listening deeply and seeking to understand their language is a natural place to start. He’s a marine biologist, National Geographic Explorer and Scientist-in-Residence at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. He founded and runs the Dominica Sperm Whale project, which since 2005 has been tracking over 20 families of sperm whales in the Caribbean Sea.

Shane Gero spoke at a Bioneers conference.

SG: And of course, now we know that humans aren’t the only cultural animal out there. Animal culture pervades all facets of their lives. And in this amazing study in chimpanzee communities across Africa, these primatologists documented the different ways, the different solutions that chimpanzees have figured out how to live. But because of the destruction of their habitat, mostly caused by us, chimpanzee communities are very isolated. And so it’s hard to understand if I never meet a stranger, do I need a sense of I am Canadian, if you just know me as Shane.

But in the world’s oceans, there’s this one ocean nomad that feels like they live in this boundless blue. And in that giant area, they are succeeding together to build multicultural societies. You see, sperm whales have been sperm whales for longer than us humans have even been walking upright, and so their stories are deeper than our stories.

Host: A prolific scientist, Shane Gero has been dubbed a “family builder.” He splits his life between what he calls his human family in Ottawa and his whale family off the coast of Dominica, the Caribbean island where he has been able to peer into the complex social lives of animals that few other humans have ever even experienced.

Several miles off the island, the warm Caribbean sun shines down on Shane and his team bobbing in their small boat. In the marine depths far below them, it’s pitch dark. At six hundred feet below, the sun fades away entirely – and that’s just the beginning of a Sperm whale’s journey into the hidden depths.

In their search for food, these immense creatures regularly venture down to 2,000 feet, sometimes as far as 6,000 feet below the surface. They spend 85% of their lives in near total darkness. The humans on the surface rock quietly in their boat, hydrophones in the water, headphones over their ears. They patiently await the familiar pattern of clicks: “one plus one plus three” that tells them the resident families of sperm whales that they’ve been studying for decades are heading to the surface.

SG: Sperm whales are all sperm whales across the globe, but how they’ve learned to live their lives are very different. In the same way that some of us use chopsticks and some of us use forks, these sperm whales differ in what they eat and how they eat, where they roam, how fast they move around, their habitat preferences, their social behavior, and to be honest, probably a myriad of ways that we don’t even understand yet. These cultures are fundamental to their identities.

And they use acoustic markers to label where they belong. And that makes these sperm whale clans the largest culturally defined cooperative groups outside of humanity.

When they talk to each other, they talk in these distinct patterned sequences of clicks with stereotyped rhythms and tempos, and we call those codas. And the norm for conversation is to overlap one another, and to match each other’s calls. And it sounds very exciting, and it has this elegant complexity to what, at least initially, seemed like a very simple system of clicks and pauses. And it sounds like this:

And right now, I’m running this large project with international researchers from around the world, across three different oceans, where we’re mapping the boundaries of these sperm whale clans. Because whales have been traditionally managed based on pretty much arbitrary lines that were defined by the whalers that were killing them.

Host: According to Shane Gero, not only are Sperm whales clearly talking to each other, but it appears their language and dialect change based on where they live. Sound familiar?

Their behavior, food choices and activities have evolved over generations of place-based learning to support the local whales’ ability to survive and thrive in the places they call home. They live as collections of families – groups of mothers, grandmothers, aunties, sisters, brothers. In other words, clans.

For the whales off the coast of Dominica, the underwater seascape and soundscape, the diversity of life from the surface to the depths – this is deep knowledge gained from transgenerational experience stretching back eons.

SG: When I think about spending half of my life learning from and listening to someone who is fundamentally different than me, I’ve taken away a lot of sort of universal lessons. Lessons like spend time with your siblings because eventually they move away.

One of the novel things that we were able to do with so much time in the company of whale families is follow the lives of the young males as they grow up and leave their families. You see, if you’re a male sperm whale, the first 15 years of your life is spent in this hyper social community of families where you’re born. When you’re a teenager, you sound like your mom, you behave like your mom, and then all of a sudden you start this incredible voyage around the world to live a mostly solitary life until you grow to be the size of about two school buses, and really become Moby Dick. [LAUGHTER]

So there’s this big shift, which isn’t so unlike our late teenage years, where you leave behind your family and go out on your own. But for the families that stay in Dominica, they learn from generations of strong female leaders – grandmothers, mothers, and daughters, who live together for life. And they’ve learned this fundamental truth that both they and we know, which is that family is critical to our survival.

Host: Shane Gero has spent literally thousands of hours in the company of sperm whales doing a deep dive of research to learn how these sophisticated animals live. Because sperm whales spend nearly 85 percent of their lives in the deep sea, learning about them involves extraordinary amounts of time spent listening to their calls, clicks and noises. His team has made leapfrog progress as they seek to understand what the whales may be saying to each other. Shane Gero spoke on a panel at a Bioneers Conference.

SG: I know what I believe they’re saying; I don’t think I know what they’re saying. But it’s pretty clear based on how they interact that they have a need to label each other as individuals, as family groups, and as clans. And that those patterns of differences emerged in such an obvious way. Once we had figured out who spends time with who, the sound overlapped perfectly. And so that explains how they might be able to not only label each other but then broadcast their own identity.

And that’s, like, a bias in how we study the whales. So I call that the dentist office problem, which is if your microphone happens to be in a dentist office and you don’t know what a dentist office is, you’re going to think the word root canal is, like, critically important to English speaking society. [LAUGHTER] Right? But it’s only because you have such a narrow picture of all of the potential contexts and behaviors that humans do when they talk. And that’s where it comes with a scale. It’s either a huge amount of boat time invested in people on the water recording across all these scenarios. Like when two cultures meet at sea, that happens very, very rarely, so the conversation of, oh, you’re not from my clan just hasn’t been recorded that many times. And the same when the males show up, born from the Azores, coming to the Caribbean for the first time, hearing that 1+1+3 click, click, click-click-click, that symbolizes or we think symbolizes the Caribbean, we’re not there necessarily when those interactions happen.

And so scaling up across contexts allows us to get the who and the what we got, but the where and the when so we can answer that why question of what are the important things that whales talk about. And that becomes a domain gap problem. Right? What is the difference between a human experience and a whale experience?

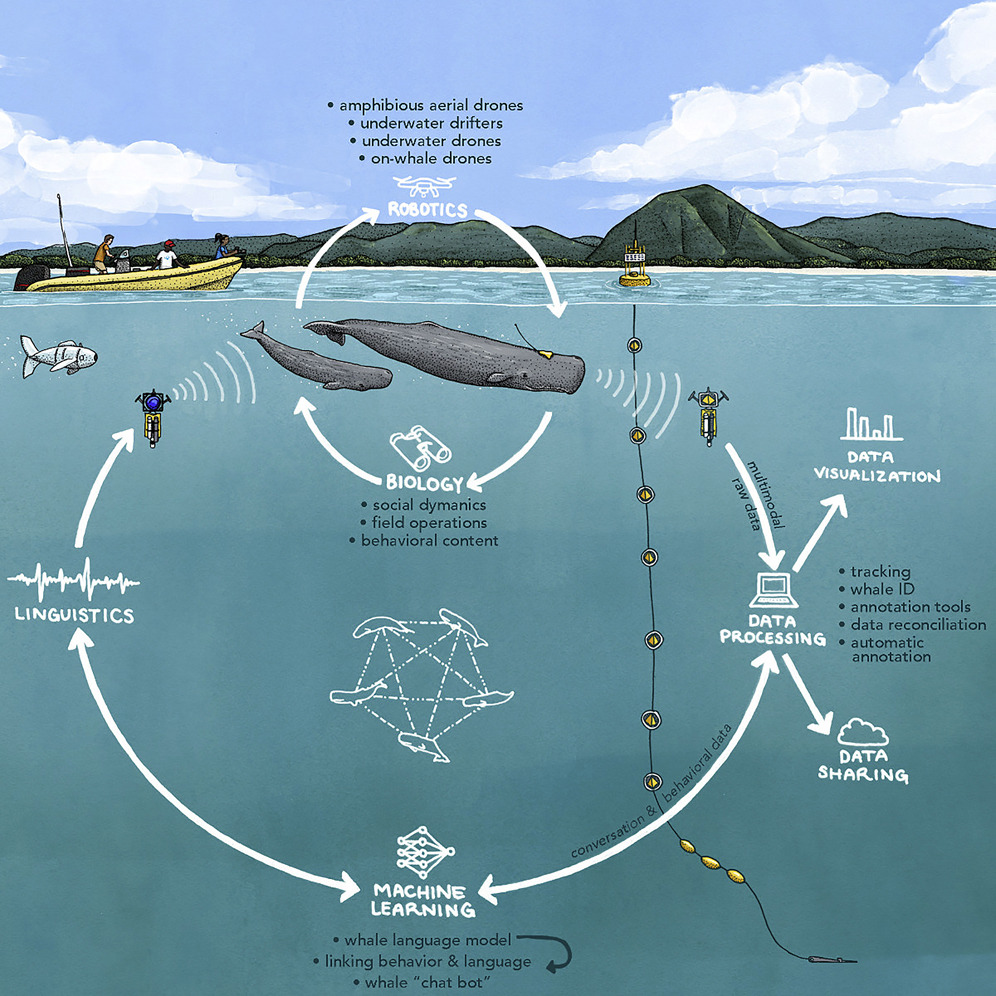

Host: To probe these interspecies mysteries, Shane Gero helped found another truly groundbreaking project. Project CETI – the Cetacean Translation Initiative – it’s an audacious effort to leverage machine learning and gentle robotics to decipher whale communication. The project builds on the tools and technologies that have rapidly transformed human language translation, such as Google Translate.

He’s collected nearly two decades of carefully tagged and coded recordings of sperm whales. It’s a veritable treasure trove of data for an interdisciplinary group of scientists who yearn to bridge the communication gap between human and other-than-human animals.

SG: I think where I find a lot of hope already with the machine learning, just even from providing this 20-year data set to these amazing modelers is that it’s blowing open the encoding space potential. Right? So when someone like myself, who have spent the better part of a number of years just cataloging all of the different calls, we’re doing that on such a basic pattern recognition scheme. Early on, literally by saying, Do you think these calls are the same when looking at them on spectrograms? And what the machines have done, quite rapidly, is open up multiple new dimensions within an individual call, within a click for sperm whales, where there is the potential for variation. So what we used to say was a 1+1+3, there’s now four different types of 1+1+3, and they seem to be used in different contexts.

So it’s not going to be Google translate next week, and there’s all sorts of reasons for that, but what it will do is give the whales a bit more credit in terms of literally defining the complexity of the information that they’re sharing with each other simply because we weren’t paying attention.

Host: As the child of a Canadian diplomat, Shane Gero grew up moving from country to country, repeatedly having to make new friends in new schools. He says he learned to observe group dynamics as a matter of social survival. He paid close attention to how various networks of friends operated.

Fast forward to today. Trained by the legendary whale researcher Hal Whitehead, he’s obsessed with watching groups of whales and figuring out their relationships with each other. Over the course of two decades of his life, he estimates he has spent nearly 5,000 hours directly in the company of these gentle giants. He’s learned not just what they do, but, increasingly, who they are.

Shane Gero recalls the story of one young whale whom he’s known since birth, nicknamed Can Opener after the white hooked shape on her right fluke.

SG: They’re individuals as much as we are, and there are some that are super curious, and especially when they’re young, about pretty much anything. So we can do things objectively and produce results and test hypotheses, but then you’re on the water the day that Can Opener decides to fake a dive.

She figured out the system that we do, which is we would get behind the whales, the whale lifts its immense tail, and we take a picture because their tails are like thumbprints, and then they dive, and then they disappear for 45 minutes. So we move up to the fluke print of where the whale just was, and we do all the sciencey things, like collect poo and record.

And what she did was see something in her environment that was doing something repeated that she could predict, and then she faked dives. And this was something that she did first, and then it kind of went through the whole community where we would come up to the fluke print, and then she would blow out all of her bubbles, and come to the surface. But importantly, she would roll her eye out of the water and look right at the people on the boat. Right?

And that’s where fundamentally the science of ‘can animals predict the future,’ ‘can animals acknowledge living and nonliving things,’ and all these questions that you can’t—I can’t as a biologist speak to, but in my mind, there’s no way that that process of events happens without complex thought and an understanding of living and non-living things.

I’ve invested so many hours trying to learn what they’re doing and who they are that the fact that they would acknowledge that we’re there is pretty substantial to me, personally.

But also just like being sort of allowed to be there, where, you know, we had these two little calves from family Unit D, they’re cousins, but the same age and basically siblings, and they’re playing and slapping each other, and making all sorts of codas, having this conversation, and it was hard not to feel like you were in their bedroom watching them mess around with their cousins, like kids do.

Like I’ve known some of the whales that I work with for longer than I’ve known my kids, which is a ridiculous thing to think about. We just had a male named Allen start to leave his family, and we found him kind of alone playing in the seaweed, you know, like maybe five miles from the rest of where his family was. And they’ve started to sort of ostracize him because he’s supposed to leave now, and he would make codas and no one would answer, and he would make these quasi-mature male sounds called clangs, but they weren’t really very good and no one was interested.

And you just kind of felt really sad for him because he’s switching from living in this super supportive community to basically spending a huge chunk of his life all alone, and it felt like he didn’t want that; like he wasn’t happy about it. And then I went back and found the first picture we have of him from 2008, and he’s like this tiny little sausage with a dorsal fin on it, and that’s—I mean, that’s so powerful to me about how these long-term projects with wildlife have so much more into them than the papers, the scientific publications that come out of them. Spending that much time following the lives of a sperm whale who’s got six years on my eldest son, is kind of like a crazy thing to think about.

I literally call them my other family. People ask me where I’m from, and I say, well, my human family’s in Ottawa, and then people kind of double take at that sentence, but it’s become so second nature to me to say it that way, you know?

Host: When we return, how understanding and honoring animal cultures can further our ability to protect the other-than-human lives of the wondrous web of life with whom we share this precious and watery planet.

I’m Neil Harvey. You’re listening to The Bioneers…

Host: In the 1960s, the acclaimed biologist Dr. Roger Payne led a legendary team of colleagues at the Ocean Alliance to collaborate with a US Navy engineer. They produced an album of songs they recorded from critically endangered Humpback whales.

The transformational experience of hearing these hauntingly beautiful songs galvanized a global movement. The epic Save the Whales campaign became instrumental in the conservation and protection of Humpback whales and ending the mass slaughter of commercial whaling. Shane Gero sees in that story several parallels in his work with sperm whales.

What if we now built a movement for the vital restoration of sperm whales, based on a true understanding of both our kinship and of nature’s intricate interdependence and diversity?

SG: We think there’s somewhere around 350,000 sperm whales left in the world, which is huge compared to some things, you know, like the North Atlantic right whale, where there’s less than a few hundred, and some species of dolphin where there’s like dozens or fewer. Right?

But it means, because they’re so spread out at this global level, it’s really hard to determine if they’re actually on a good trajectory or not, and the error on that is big enough that we don’t want to think about it. And certainly before whaling, we were talking about maybe four or five times as many whales.

And in the Caribbean, it’s quite a small clan, so the cultural group that we work with is called the Eastern Caribbean clan, and then we know of at least two other clans that pass through the Caribbean. But most of our information is about the Eastern Caribbean clan, and we think there’s fewer than about 500, and I think that’s probably being generous. And if you break that down by families that are about 7 to 10 animals, it’s only about 50 families that have this way of life of living in the Eastern Caribbean and identify themselves with that 1+1+3 coda.

Host: These distinct populations have a deep relationship with the specific places they live. Shane Gero suggests that their distinct cultural practices – how they communicate, how they find food, how they keep their offspring alive – are fundamentally different from other populations of Sperm whales living in deep relationship to the many unique other places they call home.

Any formal protection whales currently are afforded by national or international laws and treaties stems from our partial understanding only of the global population as a whole. In truth, it’s a “globalocal” phenomenon.

From a conservation standpoint, it’s imperative that we recognize these unique place-based groups as essential to the health and biodiversity of the entire species. Asking whether cultural diversity or biodiversity matters more is asking the wrong question. The answer is yes, both are true and it’s all connected.

SG: Sperm whales have typically been treated just as sperm whales, but the science increasingly, in sperm whales and in many other species, is that the important population divisions are based on culture, and that the animals are literally self-identifying in the evolutionarily important unit.

We know that genetics can’t capture the diversity that we’re trying to protect, right, which is your grandmother’s grandmother’s secret on how to survive in that space.

We’ve been fighting for a while now just to build this map of where the cultural boundaries are, so we have this empirical map that says this is where the management units are, and there’s so many more; this is where the cultural boundaries are, and we need to act on that now. Because it has been easy to say, well, we just don’t know yet. That’s often the hardest argument for conservation is, well, we don’t really know yet. Well now we know, so what are we going to do about it?

We’re going to do things differently because we listen to and learn from those to whom it matters the most. And we need to do that now, because sadly we’ve been killing whales for hundreds of years, and we do so now mostly out of ignorance rather than intent. We hit them with our ships from the ever-growing shipping fleet that brings us the economy from around the world. We entangle them in our omnipresent leftover fishing gear.

And every calf counts. When you have small families that desperately need females to perpetuate themselves, if they don’t survive, you lose the family. And when we lose a family, we lose generations of traditional knowledge of how to succeed as a Caribbean whale. And that can’t be replaced, even if the global population could swim into the Caribbean again, because these would be different whales from elsewhere who do things differently, who’ve learned from different grandmothers and are missing the solution on how to succeed there.

So these cultures aren’t just animals who’ve learned to do things differently because they never meet. These are really the link between the ocean that they live in and the animals that live there. It’s a bond between where and who.

And that’s why we can’t just do wildlife conservation based on total numbers or genetic stocks. We need to have the definition of biodiversity include cultural diversity. [APPLAUSE] These secrets are the secrets that are allowing these species to survive. They’re the viable solutions to species survival, and we need to model our framework for conservation around that.

If you can take one message from the culture of whales, it’s the power of community, that in the face of these unimaginable obstacles, the solution is to come together, and the last few years have taught us to do the exact opposite.

They’re fundamentally different from you and I, there’s no doubt about it. Right? But we can talk about shared values that we all understand. Learn from your grandmother. Love your siblings. Be a good neighbor. Because if we’re going to preserve life, ours and theirs, we need to find ways to coexist above and below the surface, and value cultural diversity in our society and our ecosystem. Thank you.o your imagination, calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting, over and over again, announcing your place in the family of things.

Host: Dr. Shane Gero… “Deep Listening: Whale Culture, Interspecies Communication, and Knowing Your Place”