Inside the Wild Pharmacy: How Chimpanzees Use Medicinal Plants and Why It Matters for Us

Bioneers | Published: September 4, 2025 Ecological MedicineEnvironmental EducationNature, Culture and Spirit Article

When chimpanzees fall ill, they don’t have the option of pharmacies or prescriptions. Instead, they draw on an inherited knowledge of the forest — selecting specific plants, bark, or leaves that can fight infection, kill parasites, or ease symptoms. This behavior, known as self-medication, reveals a sophisticated relationship between animals and their environment. It’s a field of study so specialized that only a handful of researchers in the world focus on it.

Elodie Freymann is one of them. A self-described “unlikely scientist” from a family of artists, she began her academic life studying anthropology, with an early obsession for both plants and primates. Her path wound through documentary filmmaking before a leap into graduate school at the University of Oxford revealed the perfect niche: studying how animals, especially Ugandan chimpanzees, use medicinal plants, and what that means for conservation, human health, and our understanding of the natural world.

Freymann now works at the intersection of primatology, ethnobotany, and storytelling. Her research not only uncovers which plants chimps use to heal themselves, but also explores the overlap between human and animal “medicine cabinets” — a shared knowledge that could help protect species and ecosystems alike.

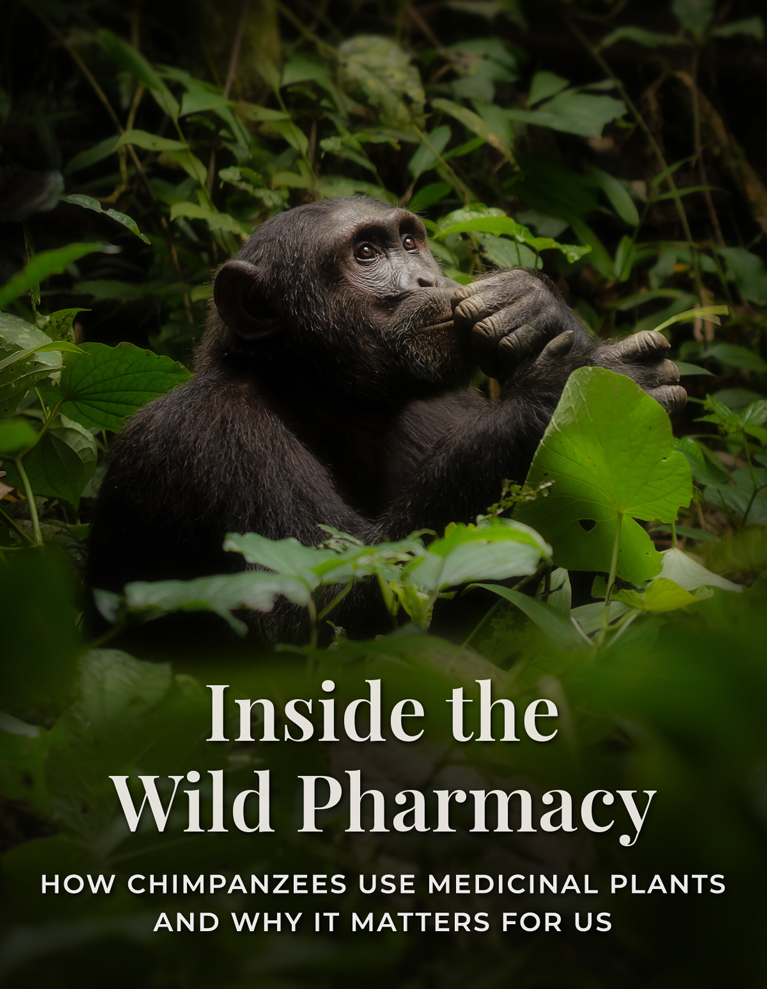

Budongo chimpanzees (Credit: Elodie Freymann)

Bioneers: What led you to your field site in Uganda, and how did you shape your approach to studying chimpanzee self-medication there?

Freymann: I knew I wanted to study chimp self-medication, particularly their use of medicinal plants — something I’ve been fascinated by for a long time.

Because it was during COVID, fieldwork logistics were tricky. One thing I hadn’t realized until I was in the field was just how competitive it is to get a spot at a chimpanzee field station. There are only a few chimp communities in the world that are habituated to researchers, meaning they’re comfortable with people quietly following them, and you can’t have too many people in the forest at once without disturbing them.

I got incredibly lucky. A spot opened up, and at the end of April 2020, I got an email saying, You can have this field site in Uganda, but you need to be ready by early June. I had about a month to prepare for a four-and-a-half-month trip — the first of my two PhD field seasons.

A short film documenting Elodie Freymann’s daily routine during her time in Budongo, Uganda (shot by Austen Deery).

Before that, I’d only seen a chimp maybe once in a zoo. I had this obsession; I had done my master’s on chimp self-medication, but this was my first time doing that kind of fieldwork. From day one, it was everything I had imagined and more.

Before arriving, I studied the feeding list of plants that the chimps at this site typically eat. I did an in-depth literature review to see which of those plants had known medicinal properties or ethnobotanical uses — traditional medicinal uses by local people. That gave me a “candidate list” of species to pay close attention to.

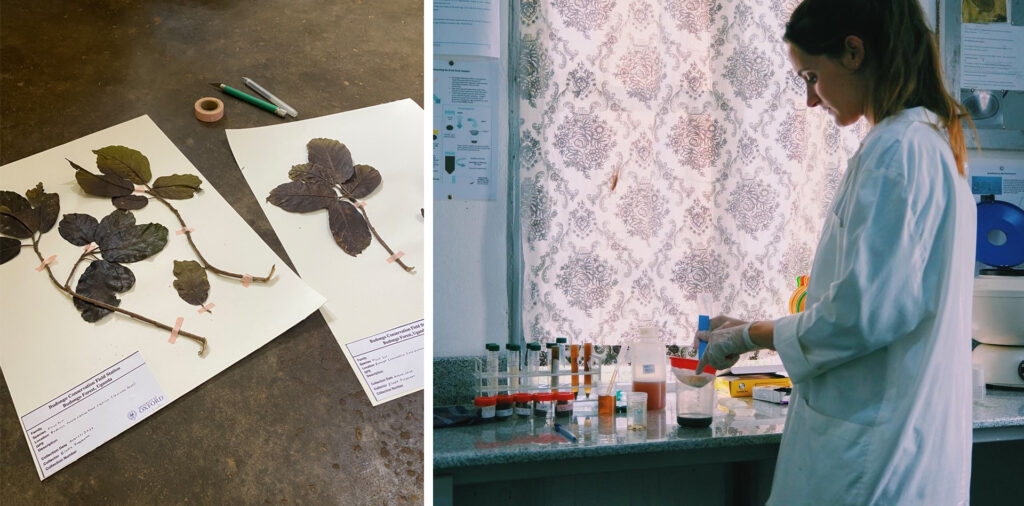

Once in the field, I focused on those plants but kept an open mind. I documented everything: videos of feeding behavior, notes on any chimp showing possible signs of illness, fecal samples collected to check for parasites, and urine samples collected to look for infection. I also got to conduct some interviews with traditional medicinal healers who lived in the region. I cast a wide net because I didn’t know exactly what I’d find.

Back from the field, I synthesized all the data, looking for connections between illness, unusual feeding behaviors, and plants with medicinal potential. My collaborator in Germany, Dr. Fabian Schultz, tested some of those plants for their pharmacological properties, checking for antibacterial or anti-inflammatory activity.

My PhD ended up spanning multiple disciplines, including elements of ethology, pharmacology, and ethnobotany. I even got to incorporate some of my scientific illustrations. I also received a grant from the Explorers Club to make a film about the project, which allowed me to use my filmmaking background to tell the story of why protecting these medicinal resources matters for both chimps and the local communities that rely on many of the same plants.

The Budongo Forest faces serious threats: illegal logging, increased snaring during economic hardship (often targeting other animals but harming chimps as bycatch), and the looming possibility of an oil road through the forest due to oil reserves found under nearby Lake Albert. That’s why documenting its cultural and medicinal value is so important — to make the forest worth more alive than dead, and to strengthen the case for protecting it against future threats.

Geresomu, field staff member at BCFS points out a tree to Elodie as they walk in the forest (Credit: Austen Deery)

Bioneers: Can you share a specific example from your fieldwork that illustrates how chimps may use plants as medicine?

Freymann: One example that really stands out is August 26, 2021 — still fairly early in my first field season. I’d been there about two months, long enough to recognize most of the chimps and get a sense of their typical diet. There are certain staple fruits and resources they eat every day when available, and a couple of big fruit trees they’d been visiting constantly.

I’d been keeping an eye on two orphaned brothers who cared for each other. The older had adopted the younger after their mother disappeared. One of them had been acting lethargic and whimpering more than usual. I also knew from earlier fecal samples that the younger had a high parasite load, so I considered them potential candidates for self-medication.

“What struck me was that the vine showed tooth marks in various stages of healing, meaning it had been chewed on many times before, even though no one had observed it happening.”

One day, they broke off from the group, which is unusual, and traveled far in the direction of a neighboring chimp community. That’s risky because chimps are territorial, and crossing into another community’s range can be dangerous. Along the way, they stopped to feed on several unusual resources — items not normally part of their diet or with very low nutritional value, like bark, pith, or dead wood. Many of these were already on my list of candidate medicinal resources to watch for.

Then the younger brother suddenly branched off and ran into a small clearing. He began chewing on a woody vine that had never before been seen being eaten by the Budongo chimpanzees. I knew this because it didn’t appear anywhere on their known feeding list. What struck me was that the vine showed tooth marks in various stages of healing, meaning it had been chewed on many times before, even though no one had observed it happening. The younger chimp chewed for a while, then his brother joined in.

Identifying the plant was tricky since it only had one small leaf. Eventually, we determined it was Scutia myrtina, a species known in the ethnomedicine literature for having strong anti-parasitic properties. It was such a satisfying moment. It was anecdotal — not something you can quantify through numbers and statistical models — but it fit together perfectly when you considered the full context: the individuals’ health, their recent behavior, their diet that day, and the unusual nature of the plant.

When I returned for my second field season in 2022, I continued to observe similarly intriguing anecdotes, especially around bark-feeding behavior, and dug deeper into investigating those patterns.

“I love the idea of these shared ‘wild pharmacies.’ . . . It’s fascinating when we’ve independently arrived at the same medicines.”

Bioneers: Your work doesn’t just reveal how chimps heal themselves — it also highlights overlaps with human medicine. How do you see those connections shaping conservation and our understanding of health?

Freymann: Chimpanzees are one of our closest living relatives, and we share a huge amount of our genetic makeup with them. What’s medicinal for humans is often medicinal for chimps as well, which is part of why, tragically, they were used in medical and pharmaceutical testing for so long.

For me, one of the most interesting directions of my research is looking at the overlap between the medicinal resources used by people and those used by animals. I love the idea of these shared “wild pharmacies.” Humans often fall into the trap of thinking we’re unique and superior in every way, with a better understanding of the natural world than animals. But many animals actually share this medicinal knowledge with us, appearing to have a deep understanding of the medicinal “cabinet” available in their environments.

It’s fascinating when we’ve independently arrived at the same medicines. That connection can also be a powerful conservation tool: If people understand that both we and other species rely on the same resources, it creates more incentive to protect them.

For animals, access to these medicinal resources is just as critical as food or space. Even if we protect their habitat, if they lose access to the plants they need to fight illness, their survival is at risk.

As climate change accelerates, we’re going to see more global health challenges like pandemics and antibiotic resistance. Animals will face those same challenges. If they don’t have access to their “medicine cabinet,” they won’t survive, and that loss will affect us as well.

Medicine is a topic most people can relate to because everyone knows what it’s like to be sick and in need of treatment. Animals have that same fundamental need, and recognizing that can help us see just how interconnected our health and theirs truly are.

“I think this research gets people to creatively stretch their thinking and give animals credit in ways they might not in their daily lives.”

Bioneers: How have people reacted to your findings on chimpanzee self-medication, and what do those reactions tell you?

Freymann: It’s been really well received. I’ve always thought it was the most interesting topic in the world, so I’m obviously biased. When other people think it’s cool, I’m like, Yes! Exactly.

I think this research gets people to creatively stretch their thinking and give animals credit in ways they might not in their daily lives. It’s funny reading comments when my papers get picked up in the news. Reactions tend to split: Some people are like, Oh my god, chimpanzees self-medicate, that’s incredible! And others say, Well, of course they do. Why wouldn’t they? Honestly, I have both reactions myself.

And it’s not just chimps or apes — it’s geese, civets, bears, even insects like ants. Self-medication is common across the entire animal kingdom. It makes so much sense. Medicating is as important as eating — it’s survival after all.

Bioneers: How are you building on your chimpanzee research, and what new projects or goals are you taking on?

Freymann: I plan to keep working with chimps; they’ll always be my first love, and I have students continuing some of the work in Uganda, so I hope to stay connected there.

But my next project, which I’ll be conducting as part of my postdoc at Brown University, is actually taking me to the Peruvian Amazon. It’s still focused on animal self-medication, but in a high-elevation tropical rainforest with a very different mix of species. Working in collaboration with members of the Asháninka community, we’re identifying medicinal plants important to the community and then tracking which animals use them. Because most wildlife there is nocturnal or wary of humans, we’re relying on camera traps and other indirect methods. The biodiversity is stunning — spectacled bears, jaguars, giant armadillos, tapirs — and seeing some of these incredible and endangered animals appear on our camera traps has been a childhood dream come true.

Long term, I want to develop a methodological toolkit for studying self-medication that can be applied across species and habitats. I’m also working with lawyers and policymakers to create a protocol for protecting the medicinal knowledge of non-human animals — essentially, intellectual property rights for wildlife — an ethical dimension of the field that I think is long overdue.

Bioneers: How do you see filmmaking and other creative work fitting into your career going forward?

Freymann: I’d love to make another short documentary. I’m still finishing the second of two films I made in Uganda. One is already done, and the other is almost there. It tells the story of a single medicinal tree used by both chimps and people, and the efforts to protect it before it disappears.

In Peru, I’m hoping we can also create a short documentary. We’ve taken some pilot footage and plan to put together a sizzle reel to pitch for funding.

I’ve made a promise to myself to not separate my science from my storytelling. I never want to take on a project without finding a way to share it creatively. When you’re working with endangered animals and fragile ecosystems, simply doing the science isn’t enough. Having the privilege to be in these places means I have a responsibility to share their beauty and importance with the world in ways that reach beyond the scientific community.