‘Come as You Are, Bring What You Can, and There Will Be Enough’ with Jasmin Graham

Bioneers | Published: January 31, 2025 Restoring EcosystemsYouth Article

Jasmin Graham (29 years old) is a shark scientist and environmental educator, the 2021 WWF-US Conservation Leadership Award recipient, and the Co-Founder and CEO of Minorities in Shark Sciences. Minorities in Shark Sciences is an organization dedicated to supporting gender minorities of color in the field of marine and shark sciences. They provide fully-funded and community-centered opportunities for research, education, and conservation. Jasmin is also the MarSci LACE Project Coordinator at Mote Marine Laboratory, which is an initiative that opens doors into marine science research, education, and careers for underrepresented minority students.

In this conversation with Bioneers Youth Fellow Anna Steltenkamp, Jasmin speaks about what an expansive view of science means—beyond the Western definition, research model and valuation process. She shares how her own work prioritizes uplifting and ‘legitimizing’ a multi-generational wealth of knowledge that spans diverse cultural, socioeconomic, and educational backgrounds. Jasmin reflects on the pivotal experiences and relationships that cultivated her admiration for the ocean and sharks in particular, and then she expands on her journey through academia and the importance of inclusion and belonging in the science and conservation fields. Throughout, Jasmin deeply explores the question: How do we welcome people’s whole selves into these spaces, whereby their unique lived experience, stored wisdom and identity expression are respected and appreciated?

This article is part of “Passion, Power, Purpose: Global Young Leaders Weaving Care for Person and Place”, an upcoming media series produced by Anna Steltenkamp as part of the Bioneers Young Leaders Fellowship Program. Learn more about the Bioneers Young Leaders program.

Jasmin: I work with communities that haven’t traditionally been heard in conservation, including fishing communities like where my family is from in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. One of my big projects is a local ecological knowledge study that I’m doing with my dad, who is a fisherman in Myrtle Beach. I also run Minorities in Shark Sciences, affectionately called MISS, which was founded in 2020 through a tweet. It was during a time of a lot of unrest and political activation when there was a big upswell of the Black Lives Matter movement. There was a hashtag #BlackinNature going around with people posting pictures of themselves enjoying nature. It was this really beautiful movement on Twitter to say Black people should be able to exist in nature without fearing that we’re going to be harassed, or have the police called on us, or shot.

I came across a picture of one of my future co-founders, Carlee, doing shark research, and I got really excited because I’d never seen anyone that looked like me doing shark research. I felt like I was the only one. I responded to her tweet: You’re a Black girl that studies sharks? I do too! We had our other two co-founders come into the conversation and say: Black girls that study sharks? We’re here! It started out as DMs joking that we should start a club, and it turned into a nonprofit, a whole movement, which four years later now has 500-plus members in 33 different countries. It’s pretty wild that the call was made and the answer was overwhelming.

If you aren’t hearing all voices, you aren’t getting the whole picture, and therefore you can’t actually tackle conservation problems.

We have a vision where seeing a person of color studying the ocean is not weird, where it’s normalized. We preserve biodiversity with sharks, but we also preserve diversity among scientists who study sharks and do conservation because we feel true innovation comes from having people with a diversity of experiences and backgrounds. If you aren’t hearing all voices, you aren’t getting the whole picture, and therefore you can’t actually tackle conservation problems. We’re all about engaging people, whether as scientists working in the field or as community leaders using science as a tool to protect the resources of their community.

We also have an expansive view of what science is—beyond what has traditionally been seen as science. We want people to have the resources, knowledge, and tools that they need to engage in the protection of our oceans because it impacts all of us. We live on a blue planet, and if the ocean ecosystems were to collapse, you’d feel it. Everyone should be part of the conversation, not just a select few powerful people. They shouldn’t be the only ones making the decisions because they don’t have the whole picture.

Anna: MISS has grown quickly since its founding. Would you share some of the main initiatives MISS has implemented to drive positive change and make science more accessible and inclusive?

Jasmin: MISS has three arms. One is outreach and education, which is all about teaching people how to engage on a community level. All of the ways that we can meet people where they are, that’s where we go, and we serve K thru Grey [all ages]. When you are capable of making thoughts, you are capable of action, and you are capable of acting until you step foot in the grave. That’s our feelings. It’s never too late or too early to engage, and we’re all about getting people in contact with the natural world and teaching them about how what they do impacts it. Then we have our professional development arm for folks who want training on certain equipment and research skills. We provide all sorts of events that anyone can attend for free, all expenses paid, and we offer stipends to offset the time taken away from family or work. We never want there to be a financial barrier to access training.

Last, we have our research arm. A lot of the folks we work with are one-person shows who are like: I don’t have any money or a building. I’m doing this totally grassroots. I just care about my community. We support by providing infrastructure, helping with grant writing, and fiscally sponsoring projects so that we can combat the way science is right now, which is that you need to have an institution and a title to be trusted with money or resources. We disagree with that, and we’re going to fight to change that. But in the meantime, here’s a thought: we just give everyone a title. Now you are a community researcher within this organization. Now you are ‘legitimized.

What if we trusted people to do the work that they’re doing, gave them the power to do it, and we were just here to help instead of trying to take over?

Anna: You mentioned that your programming welcomes all ages. Would you speak more to this experience of cultivating a multigenerational space and why it’s so important to welcome students across generations?

Jasmin: It’s so huge. To me it seems so straightforward, and yet everyone acts like it’s very innovative. You get the wisdom of the elders and the excitement of the youth all in one place. Our youth are an unappreciated powerhouse. In a lot of conservation spaces, people are starting to recognize the impacts of youth, but not with the same value as those of non-young people. There’s a difference between inviting someone to the table and valuing their voice. I noticed this at Capitol Hill Ocean Week. There were panels, and then there was a youth who responded to the panel. I thought to myself: Why not just put the young people on the panel? There’s this idea that your value only increases over time. Therefore the older you are, the more you know, which is not necessarily true. It means you have had more experience; it doesn’t mean that you are right.

On the other side, we have older folks whose knowledge isn’t valued because it’s not in the same acceptable form that the Western world has viewed as valuable. That’s where my local ecological knowledge study came from. My grandmother was one of the best fish scientists that I have ever known. She wouldn’t have called herself that, and I don’t know that she really had a concept of what science was, in the traditional sense. But, she could tell you what fish you were going to catch based on the way the wind was blowing and what was floating by—that is a really deep understanding of ecology. I remember going through school and being like: My grandma taught me that. She didn’t call it that, she had a different name for it, but that’s what it was. But her voice was not valued because she was largely illiterate, didn’t finish grade school, and was poor and Black and fishing in the South.

This local ecological knowledge study is about harnessing all of the great knowledge that fishermen in my dad’s community in Myrtle Beach have and inserting their voices into the scientific literature to make it citable. If I take all of these people’s knowledge and put it in a journal, once it makes it through peer review, it’s ‘legit’ and going to be valued—that’s what you [the Western World] said. It’s upsetting that we have to do that, but until the systems are broken, we have to help people get around them to have their voices legitimized and recognized in the science space.

Anna: I would love to hear more about what it’s like working on this project with your dad and his community.

Jasmin: It’s been pretty cool working on this project. I first approached my dad with this idea to interview people and write a scientific paper together, and he was like: What? I don’t do science. I responded: You do though. You actually know more about this topic than I do, so you should help me because you have all of these years of experience that I don’t have. Sure, I know how to form an open-ended interview and analyze the data, but you know how to talk to this community in a way that I don’t know how to—and that’s the value you bring. So he came to all of the interviews with me.

He knew to ask things that I didn’t know to ask because he had the context for what they were talking about. He could ask a question that would trigger them to expand on something that I would have missed if he hadn’t been there. My dad is a really joyful person who is well respected in the community and has known all of them for a long time, so it feels less like work and more like coming home. A lot of people have asked: How did you get the fishermen to talk to you? Most scientists can’t get fishermen to talk to them. Have you tried being a human talking to another human instead of a scientist talking to a research subject? That helps.

Then, when writing the paper, he was a large contributor to the introduction, contextualizing the economic and social dynamics of Myrtle Beach in the time period when all of these people were fishing. I was able to talk to him and my aunts. He would say: I remember when the beaches integrated, but I was too young to understand. You should ask your Aunt Rose. That’s a very important context when talking about a Black fishing community that couldn’t legally access that water until a certain point in time and how that impacted their fishing. Then, when submitting a paper, it won’t let you skip affiliation. I asked my dad: What do you want me to list your affiliation as? He said: I don’t know. I’m not affiliated with anybody. Jasmin’s dad. We ended up putting ‘fishing community member.’ I realized that this process wasn’t made for people like my dad to engage in.

Science is asking a question and trying to figure out the answer. That’s all. You can do that in a lot of ways, and all of them are valuable.

Anna: You have spoken a few times about creating a more expansive view of science. If you were to give an explanation of what you and MISS understand science to be, how would you define it?

Jasmin: This is something that we say in all of our programs: doing science is asking a question and going through a process to figure out the answer. The way you do that varies, and the techniques you use can vary in complexity and length of time, but that is the scientific method. I often use this example, especially for young kids: Do you ever see ants walking in a line, and you’re curious where they are going, so you follow the line? You just did science. Your question was: Where are the ants going? Maybe you hypothesized they’re going back to their anthill. Then you followed the line, and yep, they’re going to their anthill. Hypothesis supported.

People are always like: What? That’s not science. Science requires a lab coat and a PhD. No, science is asking a question and trying to figure out the answer. That’s all. You can do that in a lot of ways, and all of them are valuable. It’s just as valuable to say, my hypothesis is supported by generations of people doing this thing, as it is to say, my hypothesis is supported by an experiment conducted in a controlled lab environment for a period of time. If it answers your question, it’s a valid tool.

Our work at MISS is very experiential and learner-driven. Getting people to learn in a way that is conducive to them and what they’re interested in is the beautiful part about doing informal education. All of our programs have a component of independence to them. You come up with a question; you follow that thread to get somewhere. Guided journeys to discovery, not lectures, really make people connect with the scientific method. Our summer camp is held on an island in the middle of a nature preserve. There is a lighthouse, classroom and dock. That’s it. I remember during our first camp, we got to the island, and the kids were like: This is wild! We’re going to be here in the wilderness for a week? The only way to get off this island is that boat? Correct.

Seeing the apprehension at first because they have never been so far from civilization. There’s bad phone service and no air conditioning. What are they going to do? All of that shock. The first night, all of these parents and guardians are calling: My child is concerned. They’re going to panic, but that’s part of the process. Then the next day the kids are like: Wow, this is actually really cool. I’ve never been this free before. I can run around this island and just explore and ask questions. Then the parents are calling: I haven’t heard from my child in days. Are they alive? Yes, they’re just having fun. We work with youth to get them comfortable being outside and exposed to nature, because it’s easier for you to appreciate something that you know and have experienced.

Anna: Speaking to the value in early opportunities to connect with natural spaces, would you share more about your own experiences with the ocean as a young person?

Jasmin: Fishing with my dad was a huge part, being out on the pier and learning about fish by actually holding them. Also this beautiful relationship between my family and the ocean as a source of food and sustenance, and that the community exists and thrives because of the ability to fish. That area was, and still is, a food desert. The majority of the food comes from the ocean, so being able to say this is a place that is beautiful, brings me calm, and also literally fuels my life.

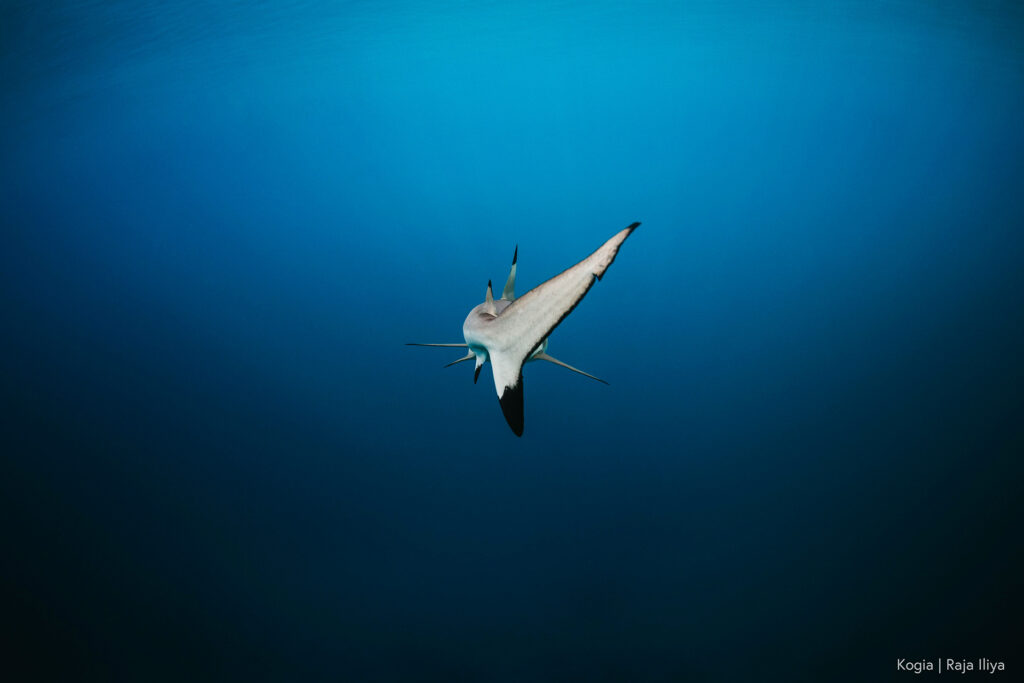

Whenever I go to the ocean, it’s similar to people going to church. It’s a very cathartic experience to look out on the water and connect with something bigger than myself. The more you look, the more life you see. You can sit on a dock for hours and see all sorts of life: pelicans diving, jellyfish and seaweed floating by, fish jumping, little ripples of water from some predator chasing bait fish around. At first glance it doesn’t look like anything but water, and then you keep looking, and you see all of this activity. It’s very beautiful and powerful that all of this life is going on beneath the surface that you can’t see unless you care to look and pay attention.

Anna: And why focus on sharks in particular?

My interaction with sharks as a kid was with fishing. Someone would get a shark on the line and everybody would quickly reel in because the sharks would run and tangle up all of the lines. I never really got to see sharks up close because they would break off, or fishers would dehook them hanging over the dock. Then in college, I met a professor who was studying sharks, and I went to work in his lab because he was the only professor who was willing to pay me. Marine science has a big problem of expecting people to work for free.

I fell in love with sharks and realized how cool they are while we were studying genetics and phylogeny [how different species are related to each other]. I learned how old they were and how little they had changed in the grand scheme of things. We went from T-Rex to chicken—the closest living relative to a dinosaur is a chicken—and yet prehistoric sharks look pretty much like sharks do now. I thought it was really impressive that they had millions of years of opportunity to change and instead were like: I’m good. This works pretty well. Also the fact that people dislike them so much made me like them even more, because I wanted sharks to have better PR [public relations] people. Dolphins and orcas get movies like Flipper and Free Willy, and then sharks get Jaws? Why do some species get to be friends with small children while sharks are portrayed as eating children? That’s not fair PR.

Here’s this misunderstood animal, and people make assumptions that its very simple behaviors are aggressive. I see a parallel between sharks and Black people. Sharks are seen as scary or threatening by default. We have news stories of a shark swimming down the beach in Miami, minding its own business, with the headline: Killer Shark Stalks Beachgoers. It didn’t bite anyone. It literally just swam past. I see it the same way with how the news portrays Black people: something happens, and it’s always the most thugged-out picture of the person that’s used.

There’s this misunderstanding and misinterpretation of sharks, meanwhile they’re actually the ones under threat. [Over the last 50 years, there’s been a 71 percent decline in oceanic sharks and rays, according to research published in the Nature scientific journal.] People are so busy being afraid of them that they don’t realize that we’re losing them, and that that’s a problem. Sharks are good mascots for myths when talking about ocean conservation, especially with communities who have been demonized because sharks have been demonized as well. We’re trying to combat that both with sharks and communities.

If you’re expecting people to leave part of themselves at the door, you’re losing all the value that comes with having a diversity of experiences.

Anna: On this point about creating inclusive and equitable spaces in conservation, I read your research study about the importance of a sense of belonging, science identity, and self-efficacy for career retention with BIPOC students. How did these factors affect your own journey, and how does MISS seek to strengthen them for others?

Jasmin: My experiences in academia were a mixed bag. There were some spaces where I felt like I belonged; there were others where I was made to feel like I didn’t belong. There were a lot of times where I felt that my knowledge—not the traditionally accepted form of science—was not valued. That was frustrating, especially in classes where students and professors were talking about conservation in ways that seemed very anti-fishermen. I was sitting there like: Why are we hating on the fishermen? I had classmates say: People should stop fishing. That’s the answer. The answer for whom? My family fishes for food. What are you expecting people to eat? What’s the alternative? It’s easy for you to say that when you live in a place where there’s a Whole Foods. What about people who live in a food desert and can’t get to a grocery store?

If you’re expecting people to leave part of themselves at the door, you’re losing all the value that comes with having a diversity of experiences. At MISS, our learning spaces are an open dialogue, and we’re here to learn from you as much as you’re here to learn from us—coming from the perspective that we don’t know everything. We’re all about helping people bring their whole selves and that means preparing our spaces for everyone’s whole selves. There’s a difference between feeling like you belong as long as you aren’t too ‘insert whatever.’ As long as I’m not too Black, as long as I’m not too feminine, I’m accepted here. That’s not feeling like you belong; that’s feeling like you can assimilate properly.

How people choose to express themselves at our MISS events—it’s beautiful. We have potlucks where people bring their cultural dishes. We set up a playlist that people can add whatever music they want. We actively encourage people to bring these other elements of themselves in. It does not matter what you are wearing, how your hair is, if you have tattoos or piercings. We’re not here to police how you talk or what you value. Feeling like you need to conform adds a lot of pressure. I’ve had people make comments about my hair all the time. Sometimes scientists have purple hair—doesn’t make them less of a scientist.

We have these moments to see each other as people first because scientists are people. Sometimes we act like scientists are robots that are entirely objective and have no other things going on. We’re human beings. We have biases, agendas, and values. You can try to ignore that, but it’s not true, so connecting with people on a human-to-human level first is really important to us. Connection happens in a lot of ways, but for many cultures food and music are huge, so that’s usually where we start.

Anna: In the spirit of celebrating with food, and recalling your ties to the ocean as a source of nourishment for your family, I’m curious if there was a favorite meal that you made with your family growing up.

Jasmin: There were a lot of them. We love, love, love crab. And fish fries. Fish fries are huge because if someone’s pulling out the fryer and we’re getting ready to go nom on some fish, it’s a whole community gathering. Everyone from the neighborhood is there. It’s a fun time.

I love the sense of community that comes with eating seafood, gathering people together and cooking large amounts of food—and this idea that there’s enough. That’s something that’s really important to my family. You can never not be welcome at a fish fry. Fish fries are for everyone. You could roll in off the street and nobody knows who you are, and, yeah, grab a plate. There’s never a question about whose fish is this or that. Come as you are, bring what you can, and there will be enough.

What if we existed from a place of abundance, where we were less concerned about who owned what and more concerned about the community as a whole having enough? Not having to worry about someone taking too much because everyone’s main concern is that no matter how much we have, everyone gets enough. That is a fish fry. No matter how many fish we have, everyone gets to eat. I don’t know how it happens, but it does.