Layla K. Feghali | Food is Our Medicine, Love is Our Medicine

Bioneers | Published: January 11, 2024 Food and Farming Article

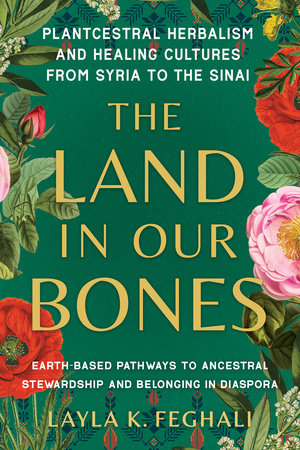

Tying cultural survival to earth-based knowledge, Lebanese ethnobotanist, sovereignty steward, and cultural worker Layla K. Feghali offers a layered history of the healing plants of Cana’an (the Levant) and the Crossroads (“Middle East”) and asks into the ways we become free from the wounds of colonization and displacement in her book, The Land In Our Bones.

Purchase The Land In Our Bones here.

Food is Our Medicine, Love is Our Medicine, by Layla K. Feghali

My maternal Teta’s (grandmother’s) house was a universe unto itself. Time and space would cease to exist there. Teta had been living in the US since the ’70s but her house still smelled, felt, and tasted like the tiny southern village she came from, possibly even the same version of it she left before war and occupations, before the family moved to Ras Beirut, before they traveled oceans, before it all. We would come visit her often in the springtime when we were children. Easter was my Jiddo’s favorite holiday, and I recall the festivities of that season and the rituals it entailed. All our maternal aunts, uncles, and cousins lived in Florida except for us, so our visits were special and brought completeness to the family for a moment. There was always lots of food.

Teta’s house was a capsule of our memories. Every room contained its own secrets and stories from our childhoods. Etchings on the walls we got scolded for and height charts to archive our growth—our own lexicon of stories were left as testaments in every corner. Every drawer and closet had some old remnant from the family’s life in Lebanon, or the handmade clothes our mothers crafted when they were our age. Every drape and couch, every item of Teta’s clothing, all the adornments in the home were sewed by her hands. The whole place smelled like fresh grown za’atar, so much so that my clothing would always linger with this smell when I got back to California. At certain points in the day, all my aunts and uncles would arrive in a simultaneous cascade, the rakweh would boil and black bitter coffee would make its way to the living room where everyone collected to banter for a moment before going back to their daily work. There would always be a couple people playing tawleh (backgammon) on the other side of the living room while the rest of us sipped, and someone else in the kitchen rustling around for bizr (seeds) or fruit to snack on with the coffee. Undoubtedly, ahweh (coffee) was and remains the most steady and sacred ritual of all in my mother’s family. The moment in the day when everything else would stop and we would all be together, in Teta’s house, doing what families do, what village folk do, thousands of miles and decades of time away.

While the living room was the heart of the house where this ritual would take place, the soul of the house lived somewhere between the kitchen and Teta’s prolific garden. For our people, and for my family, food is love, and culinary love is deeply and fundamentally communal. To share a meal or drink together is the most significant (and mundane) ritual of connective care, and it is also our primary vessel of botanical medicine. Our traditional foods are the first line of physical defense and fortification, as well as the initial method of treatment should an ailment arise. Furthermore, the seasonal nature of our traditional cuisine revolves around wild and baladi (homegrown, organic) crops whenever available, anchoring the traditional eating culture within the cycles of local land and its inherent intelligence and embedded medicinal properties and vitality. It is part of the unspoken way our communities calibrate to place and to one another.

This played out naturally in Teta’s house. There was a tiny island in the middle of her kitchen, which always had a small container of za’atar next to one of zeitoon (olives), a bag of mar’oo’ bread handmade by her, and a little jug of olive oil. At most points of the day, there would be at least a few of us sitting there, eating, snacking, or helping Teta roll grape leaves or prep a meal. In Teta’s house, every ingredient and step of the food preparation process was approached with great respect. The kitchen led to a side room that stored additional cooking equipment, and a garage where her saj oven and distiller and an extra freezer dwelled, which led to the nursery of her garden where she grew parsley, zaatar, sage, and every other basic vegetable and herb of the Lebanese cuisine you could think of.

Teta’s garden was her place of refuge and pride, and she was known in the family to have ’eed barakeh بركة يد”) a blessed hand,” or what we call in English a green thumb) that could manage to help any plant live somehow. Okra, cucumbers, eggplants, tomatoes, figs, oranges, and of course roses. All of these fresh greens would make their way into our meals prepared with undeniable love and packed with nutrients and protective medicine. The resourceful, seasonal, and natural qualities of the materials emphasized in Teta’s house were always significant, and it was something my mother carried forward in our home too, she perhaps the most dedicated foodie of our whole family. Just as they insisted our clothing be made with cotton, silk or other natural fibers, the grains, meats, and vegetables utilized in our meals were chosen with a grueling discernment and attention to flavor, freshness, and quality entrenched deeply in our land anchored culture. The love inside food prepared and shared was demonstrated by each detail of care and skill invested, the medicine ensured by insistence on cleanliness and homegrown ingredients wherever possible. In Teta’s house and the lineage of her children, food is truly devotional.

The vibrancy of communal preparation, the songs, kinships, and comfort that naturally emerge in the process of making together is the unspoken niyyeh, the underlying intention and purpose inside Cana’an’s traditional food customs. The colloquial and social nature of food in our culture is in and of itself medicine, reinforced by the potency of plants, reflecting a deep paradigm of health embedded in collectivism and mutual stewardship of season, kinship, and place. Companionship is the most consistent and primary ingredient in our traditional food remedies.

While my mother’s family may be particularly invested in the ritual of traditional food preparation, its centrality in our home is not unique in our cultural context. Every aspect of culture across Cana’an centers around sharing meals—be it a regular summer day, a wedding, holiday, birth, or the death of an elder. It is somewhat offensive to refuse a meal or food item offered when visiting guests and family, and they will characteristically fill your plate with more than what you asked for. Food is an expression of love and generosity, which holds a high cultural value across our region. My father’s family in Lebanon is just as food-centric; many of my favorite memories with my aunties and grandmother especially revolve around the conversations at the kitchen table while picking fresh mlokhiyeh off the stocks, or eating green garbanzos in the garden with them and my uncles—always with finjan ahweh (a cup of coffee).

The communal aspects of food in Cana’an’s tradition exists in every stage and season of its preparation—from the growing, harvesting, and sharing of crops to the cooking and the consumption. My aunt reminisces about summer returns to the village during wheat season when she was a child. Wheat was usually purchased from villages in the Bekaa Valley, where it was known to grow well, and then brought to our own village in the south to be processed into burghul (cracked wheat used in many traditional recipes). A person would ride around the village with a loudspeaker announcing that today the wheat preparation would be happening at so-and-so’s house. Everyone would then proceed to that family’s house for a day of working together to prepare the grains that would nourish them collectively for the course of the whole year. In my own lifetime, I would most often arrive to my mom’s village to find Great Aunt Lucy on the back patio with her husband and neighbors shelling pine nuts, drying sumac, or processing za’atar together, depending on whatever was in season. Locals would come and go to lend a hand as we bonded over a break to read the predictions in our coffee cups, delighting in whatever fresh fruit was currently growing. I barely know what the inside of her house looks like—most of our visits centered around the garden and its bounty.

In a similar spirit, I remember one beloved aunty in my father’s village who spent her days walking around, with her umbrella for shade, arriving at the doors of extended-family homes with the special mission to help make ma’ajanat (dough pies) together. Her dough was famous for its delicious quality, extended family vying for her special touch and support in their kitchens. Food and its preparation has always been the central place of connection, nourishment, and day-to-day care across our region. Each person has a role, a hand to extend in the seasonal process, and the generosity to give of their abundance to one another regardless of how much or little they have. Even in my parents’ home in diaspora, extended community arrives unexpectedly at the door with a huge bag of fresh tomatoes, pickled olives, or wild mallow from their garden as an offering of mutual care reminiscent of home with no return expected. It is at the very core of our culture to relate in this way. And it is also why there will always be enough to share when unexpected visitors appear.

Food itself is such a foundational and integrated part of our collective tradition that some people might miss just how meaningful it is as a form of herbal medicine. It is arguably the most tenacious, intact, aspect of our ancestral botanical wisdom alive today. Our traditional recipes themselves are balanced formulations we may not be conscious of, but we maintain in the continuation of our ancestors who first developed them, and are empowered by our union with one another in both their conjuring and consumption.

From The Land in Our Bones by Layla K. Feghali, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2024 by Layla K. Feghali. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books.