“Love, Nature, Magic” | What Mosquitoes Teach Us About Living in Balance with Nature

Bioneers | Published: September 6, 2024 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

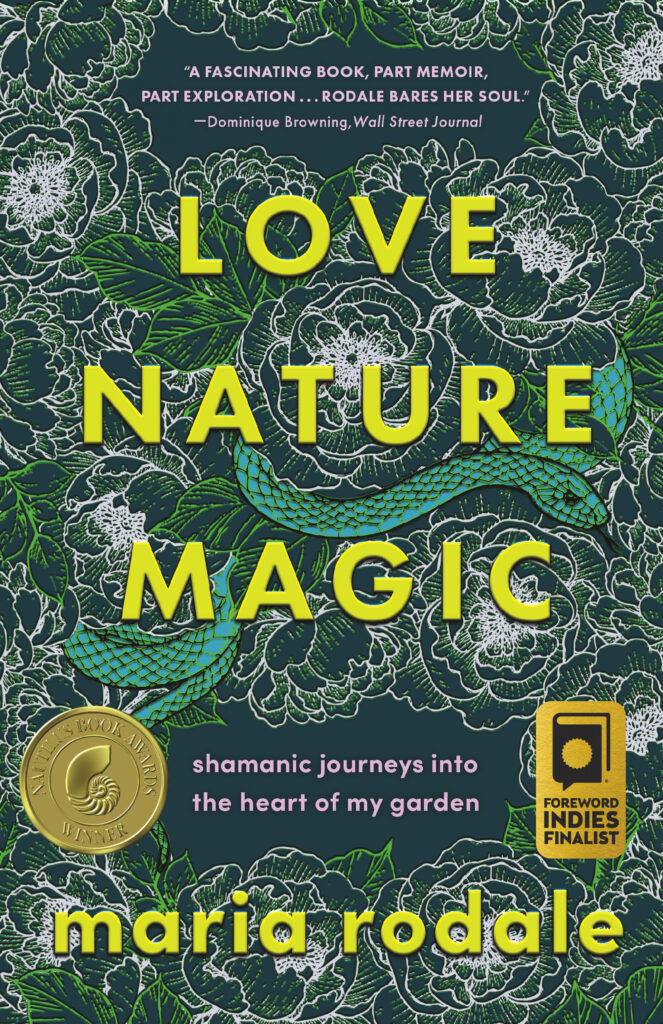

In her book “Love, Nature, Magic,” author, activist, and garden expert Maria Rodale reflects on her surprising conversations with the spirits of the familiar plants and animals around us — and the knowledge they share with us. Rodale combines her love of nature and gardening with her journeys into altered consciousness, embarking on an epic adventure to learn from plants, animals, and insects — including some of the most misunderstood beings in nature. She asks them their purpose and listens as they show and declare what they want us humans to know. From thistles to snakes, poison ivy to mosquitoes, these beings convey messages that are relevant to every human, showing us how to live in balance and harmony on this Earth.

In the below excerpt from “Love, Nature, Magic,” (Chelsea Green, 2024) read about Rodale’s perspective-shifting journeys to visit one of the most detested “pests” of nature, the mosquito, and what these journeys made her realize about the insects and ourselves.

Mosquito

When we kill others, we kill ourselves.

First Journey: September 9, 2021 | Second Journey: October 28, 2021

The truth is, even though I have lots of resident bats, there are still some mosquitoes around my yard every summer. And of course they annoy me. They come out after big rains, and at those times I am never far from a tube of anti-itch cream, especially toward the end of summer. The waning of hungry late-summer mosquitoes is one of the only reasons I look forward to fall.

I am constantly traipsing about my garden looking for pots or toys that might contain standing water where mosquitoes could lay eggs. The worst culprit is old tires. It never ceases to amaze me how many old tires I can find in the woods that surround my house and garden. Over the past two decades I’ve found and removed at least a hundred. And new ones keep appearing. Like mushrooms (and mosquitoes) after a rain. I recently discovered a pile of about fifteen partially covered with moss. It’s my spring project to dig them out and send them off to wherever old tires are supposed to go, wherever that mysterious place may be. Old tires are NOT supposed to be dumped into the woods on the side of the road. People, stop doing it! Old tires are mosquito breeding factories.

Apparently, the deadliest being on planet Earth is not the wolf, the grizzly, the great white shark, or even the human (he comes in second). It’s the teeny-tiny buzzing annoying mosquito. When it bites you, it first injects an anticoagulant into your body so it doesn’t choke on blood clots as it sucks out your blood. The anticoagulant is what makes you itch. As it feeds, it also injects its saliva into your bloodstream, and that saliva can carry organisms that cause potentially fatal diseases. That’s what makes it so dangerous: mosquito spit.

I confess, I was nervous to visit with mosquitoes in a journey, but they were on my list to talk to because they are so annoying (and deadly) to so many people. I can’t say I was looking forward to the encounter, but I wanted to ask mosquitoes why they exist. It was hard for me to imagine a good reason why, and yet I was pretty sure there must be a good reason. So I just dove in . . . literally.

* * *

It’s not unusual for me to have a mental image of walking or jumping into water at the beginning of a journey. Basically, I go wherever my mind’s eye leads me. As I entered this journey, I was in a tropical jungle, and a dark murky pool lay before me. Believe me, I did not want to go in there. But rationally, I knew I would be fine—I wouldn’t wake up from my journey wet and mucky. After all, I was safe on my sofa. This pool of water is what had appeared before me as the place to go, and in I went.

As soon as I dove in, I transformed into a squirmy mosquito larva. Then I floated to the surface, emerged from the water, and flew. Somehow, I homed in on the back of a sweaty human male and drank his blood. It was delicious. Warm. I mated. Laid eggs. And died.

I was dead, and nothing was happening.

Ummm . . . hello? Hello?! Nothing seemed to be happening. Into the void I called out, “Take me to your leader!” Weirdly, I found myself transported to what I can only describe as a spaceship command center, and a giant mosquito was before me.

“We’ve been at war with humans ever since you arrived,” it said.

“But don’t you need us to eat?” I asked.

“We tend to kill what we love.”

“Huh?”

“We tend to kill what we love. There are too many people anyway. Do your homework and come back to me. But why should I help you? So you can eradicate us?”

This was turning into a really strange journey, and I felt unwelcome. As I turned to go, Mosquito stuck its proboscis into my head and injected something into my brain (probably spit). It repeated: “Come back after you’ve done your homework. We tend to kill what we love.”

* * *

I came out of the journey, and I had to admit that it was a fair criticism. I had not done my homework; I really knew almost nothing about mosquitoes other than that they were quite annoying and potentially deadly. I thought about the statement “we tend to kill what we love” and found myself wondering: Aren’t many human murders due to domestic violence — fits of rage, jealousy, honor killings? We tend to kill what we love. But how did that relate to mosquitoes?

I started reading, and one of the first things I learned is that mosquitoes are old. Like at least 236 million years old. That’s a lot older than humans.

Only the infected female Anopheles mosquito causes malaria. In fact, among virtually all mosquitoes (and there are more than three thousand species), only the females bite. And it’s not just malaria they spread. It’s West Nile fever, yellow fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, and dengue. These diseases are responsible for about 5 percent of annual deaths of humans worldwide — almost a million a year. (Although antibiotic-resistant diseases are rapidly gaining in power to kill due to the misuse of antibiotics to fatten up livestock.)

In truth, the human death rate due to murder is close to the death rate due to malaria. And as I write this manuscript, the annual death rate due to COVID-19 is way higher than deaths due to mosquito borne diseases and murder combined. We live in a deadly world. And mosquitoes are just one tiny reminder of it.

In the warm areas of the northern hemisphere, mosquitoes have been primarily a nuisance, not a threat to human life. But as global travel and trade have increased, average temperatures continue to rise, and humans create even more habitats where mosquitoes thrive, tropical diseases are spreading rapidly.

All this is interesting, but I kept returning to this: Only the female mosquitoes bite. They don’t have enough iron or protein to make their eggs, so they need to get them from an outside source — blood. (This, ironically, is also believed to be one of the reasons humans started eating meat — because we females needed the extra iron and protein to create our own babies.) Your blood goes right into a mosquito’s stomach, gets digested, and is turned into eggs. In mosquitoes, only females who have already had one batch of eggs spread disease. Think about it for a minute . . . mosquitoes by themselves don’t carry diseases, they pick them up from their sources of blood (us or other animals). And the only way they spread a disease is if they are going back to the “well” for the second time. In her lifetime, a female mosquito can’t really lay more than three batches of eggs (up to five hundred eggs in total). So it’s really a relatively small number of mosquitoes that cause disease. It’s the older ladies, in fact. (This leads me to wonder if historically the male obsession with purity in women has to do with a fear of getting diseases. Perhaps. And yet males having multiple partners is most likely how human sexual diseases spread. But I digress . . . )

Taking a break from reading about mosquitoes, I decided to watch TV. Nerd that I am, my favorite TV streaming choices are almost always documentaries. I scrolled through the listings. Hmmm. I had never watched the PBS documentary about Rachel Carson. I had read Silent Spring, which many environmentalists I respect cite as the trigger for their awakening. Also I had received the Rachel Carson Award from the Audubon Society many years ago. I was surprised I hadn’t watched this documentary before.

Welcome back to the magic of the Trail of Books (which is also the Trail of Movies and Documentaries). It’s the magic that happens when I follow my instinct in choosing what to read or watch, and it turns out to be exactly what I need to learn about.

Yes, I remembered that Rachel Carson had written about DDT. But what a book doesn’t capture that a documentary can are the actual sights and sounds from the times in which the author was writing. Including the deep, authoritative, WASP-y male voice proclaiming that through the miracle of chemistry and DDT, man has now won the war against the mosquito and will ERADICATE it from Earth, accompanied by black-and-white footage of a truck spraying clouds of white powder over kids eating sandwiches at a picnic table, and airplanes squirting white dust over fields and suburban neighborhoods while kids play outside. The HUBRIS is embarrassing to watch. Sure, mankind has eradicated a lot of species, mostly by accident or for the pleasure of blood sport — like the passenger pigeon, poor thing. That bird never bit, infected, or threatened anyone. In fact, it helped people by carrying messages from one place to another on our behalf. And was delicious to eat, reportedly. So how did we thank it? Kapow. Dead.

It’s normal for many people to want to be a hero, to want to save the day. Humans strive to eliminate enemies and control the world in order to protect their progeny from disease and death, and even more importantly, to protect and expand their wealth. But killing things (other people, pests, alleged enemies) doesn’t solve our problems. As illustrated in the documentary and a thousand scientific studies, when we try to kill things like insects or weeds or viruses and bacteria at a grand scale, they develop resistance and rise up even stronger than before, requiring even greater interventions and stronger chemicals to ramp up the fight. As a by-product of our attempts at insecticidal and bactericidal genocide, we also kill many other things that we need and love, like butterflies and bees, birds, good bacteria essential to our health, and all the amphibians. This leads to a chemical, genetic, or military escalation in which we end up killing . . . ourselves. We end up killing that which we LOVE.

Ahh. Now I get it.

Mosquitoes are an integral part to a much greater food chain. Male mosquitoes don’t bite and suck blood but eat plant nectar; they are pollinators. Mosquito larvae are food for dragonflies, fish, birds, some toads and frogs, turtles, spiders, and ants. Those water-dwelling babies (larvae) also eat algae and bacteria, which helps keep water clean. They keep our water clean. That’s important!

What, then, is the answer to the “problem” of mosquitoes and diseases? Well, as my grandfather liked to say, prevention. On a small scale, preventing mosquito breeding is about reducing standing water such as in old tires, pots, and even the nooks of plants like the bromeliads. On a larger scale, in places like Africa and South America where fatal mosquito-borne diseases are serious threats, especially for children, it’s about installing plumbing and providing clean water, secure housing, window screens, and medical assistance, including vaccines. Mosquito netting over beds is nice, but it turns out that most mosquito bites occur during the day. We need to find ways to prevent and heal the mosquito-borne diseases already inside us so that a female mosquito bite does not result in her getting infected.

Genetically modified mosquitoes (sterile male mosquitoes) have been released into the wild in Florida. This is not an optimal solution. If this technique successfully eliminates mosquito populations, the results would be catastrophic for insects, birds, and animals that feed on mosquitoes, and water quality would drastically decline.

Humans must commit to creating an environment in balance with nature, where nature’s food chain is allowed to proceed naturally. How do we do that? I think about this question a lot. It can’t be done by eliminating populations of “pests.”

Some people have argued that we need to limit human population growth in order to live in balance with nature. In the past, humans have come up with horrible methods to “control the population” of “unwanted groups.” Proponents of eugenics murdered, imprisoned, and secretly sterilized the groups they deemed undesirable, leading to horrid traumas and terrible suffering. There is absolutely no situation where this sort of behavior is acceptable, even though it still happens today.

What’s a more productive way to create balance? Education. Especially the education of girls and women. When girls and women are educated, they understand how their bodies work. If they live in a culture that allows it, they can decide for themselves how many children they want to have, and then care for those children with a greater amount of attention and ability to support them. They are also more likely to take on leadership roles in government and businesses that protect and nurture the healthy development of future children (which is why education for girls is so threatening in highly patriarchal cultures). But the education of boys and men is essential, too. Especially teaching them to learn how to communicate and connect with others in positive, constructive ways — in particular with girls and women, who are vital to their survival. The global human population could decline naturally over time, providing more breathing space for humans and nature to live in harmony with each other.

Now, before the capitalists among you freak out about population decline because capitalism is a system that requires continual growth (I’m not naming names, but you know who you are), read on. These changes need to be accompanied by a new economic model that doesn’t rely on endless growth and the domestication (aka servitude) of women to do all the household duties. This would require not just education but radical culture change — in almost every culture around the world. Men will have to pull their domestic weight — or pay real money for others to do it for them. In my view, it’s fear of this kind of change that is fueling a backlash against feminism right now, everywhere from Texas to South Korea.

Some men I know fear population decline because of the potential loss of our civilization, or human consciousness. But the more I journey, the more I realize that consciousness cannot be destroyed. It exists with or without our bodies. And every civilization and culture evolves and changes over time. It’s only natural!

People need to learn how to live in balance with nature. We also need to learn to live in balance with each other. When men and women (and everyone else) are truly free, educated, and loved, we are all better able to take care of the world around us — and enjoy it more!

It’s very possible that we don’t need to reduce our population to live in harmony with nature. But in that case education is even more essential because we must learn to create, invent, and innovate new ways of living on this very special Earth.

If we humans don’t commit to being good stewards of the environment around us — even if we don’t like what that demands of us — nature will take care of the environment in its own way. And the mosquito will be just fine. Fabulous, in fact. Meanwhile, we humans will be decimated by more and more diseases, spread not by just mosquitoes, but by our own ignorance.

After watching the Rachel Carson documentary, I found the courage to watch another one, this one aptly called Mosquito (because, obviously). It was a depressing experience, and afterward I realized I needed to go back and talk to Mosquito again, and to Bat too. After all, bats and mosquitoes are partners — predator and prey.

I decided I would journey the next morning. In the middle of the night, I woke up with these words in my head: “It’s not really the mosquito that’s the vector of disease, it’s us. Our travels. Our trash. Our toxins. Our tragic belief that killing something will make it go away.” I emailed that message to myself and went back to sleep.

One of the most depressing stories from the mosquito documentary was about mosquitoes breeding in abandoned tires. What I didn’t know before watching Mosquito is that old tires are shipped all around the world. If mosquitoes lay eggs in water trapped in a tire, and then that water dries up, those mosquito eggs are still capable of hatching once they get wet again. Even if the tire has been moved to a different continent in the meantime. The deadliest of the mosquitoes are spreading everywhere in junk tires. And because climate change is causing overall warming, mosquitoes can survive farther north, and their range of influence is spreading more and more. Car tires. Fucking car tires.

The next morning, I began my return journey.

* * *

I immediately entered the mosquito mothership and apologized for my ignorance on my previous visit.

“How can we learn to peacefully coexist with each other?” I asked.

“Ahh, now you are asking the right question,” Mosquito said. “You must heal the diseases within you. Stop killing our natural predators. Take care of your own people. Lift them out of poverty. Clean up the squalor. And stop heating up the planet. If that continues, mosquitoes will be the least of your worries.”

This time she spoke with kindness. I felt humbled and grateful to her. We even hugged. It was awkward, but still. It was a hug.

“Now, go talk to Bat.” She dismissed me.

I went back to the bat cave and the cavewoman was there. “Oh, not you again!” I said. The last time I had seen her, she had murdered me and eaten my heart. She ignored my comment and handed me the same leaf mixture I had eaten on my previous visit. I ate it, and I found myself with Bat. I had to wake her up.

“I’m sorry I didn’t ask you before, but what is your job and your purpose?”

“Our job is to keep nature in balance.”

“How can I help you?” I asked.

“Tell people to leave us alone — even the scientists and researchers! They need to respect our homes. We wouldn’t do to them what they do to us. Tell them to get their heads out of their goddamned test tubes. You can’t understand anything unless you look at the whole thing. The web of life is real.”

I thanked her. The drum was still drumming, and I wasn’t sure what to do next. Then I found myself on the electrical grid or web that I had flown through during my previous bat journey. I started jumping on the web as if it were a trampoline. I was having a bit of fun, but suddenly a bat swooped in and ate me. Now what? I asked myself. Before you know it, she pooped me out right on my side porch, where all the other bat poop is. She had brought me home. The journey was over.

* * *

Thinking about this journey, I begin to realize that once I journey to speak with a being that I am initially afraid of, I start to feel genuine affection and love for them. And that happens because we learn to trust and know each other. What was once an annoyance becomes a real friend. What I once wanted to eliminate, I learn to appreciate — I realize these beings really aren’t so bad after all. They are not my enemy. They have feelings too. Indeed, the feeling I carry out of a journey is love. I feel my heart softening and warming in ways I never could have made happen through an intellectual analysis of a creature’s role in nature — or even from watching a documentary.

And this, my friends, is why journeying is such a valuable tool. Doing research doesn’t shift my heart. It is only through a personal relationship of trust that I can learn to love those things that once were just annoyances. I can assure you, these experiences have changed how I behave in my day-to-day life, too, for which I am grateful. If anything, journeying makes me want to learn even more about these creatures — but not through the kind of research that stomps into a bat cave without regard for the feelings and rights of whatever lives in there. We must learn to respect each other’s homes and families. We must stop killing what we ourselves love. And we must even stop killing the things we don’t love. Because somebody somewhere loves them.

I have no doubt that 236 million years from now mosquitoes will still be here on Earth. Us? Probably not. I mean, how many tires will there be on Earth in 236 million years if we don’t change our way of living? A lot. (I have since learned that particle pollution from car tires is thousands of times worse than car exhaust emissions. Someone really needs to invent a new way to get around. Please.) And no, sending them out into space, like Jeff Bezos thinks we should, won’t solve our problem. Neither will sending them to Mars. The web of life is out there too. We just haven’t learned to see it yet.

I think I’m going to leave my moss-covered pile of tires exactly where it is as a reminder that all our actions have consequences. And that to stop killing what we love, we have to stop trying to eliminate those things we don’t easily like.

Thank goodness for anti-itch creams!

Thank you, Mosquito. And again, thank you, Bat.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from “Love, Nature, Magic” by Maria Rodale, published by Chelsea Green, 2024.