The Power of Art for Healing and Justice: A Conversation Between Native American Artists Joy Harjo and Cara Romero

Bioneers | Published: October 22, 2025 ArtIndigeneityNature, Culture and Spirit Podcasts

In this program, we drop in on a remarkable conversation between two world-renowned Native American women artists. National Poet Laureate and musician Joy Harjo riffs with renowned photographer Cara Romero. They discuss how life is art, and how they make their art to reflect the lived truths of their cultures and people.

Featuring

Joy Harjo is an internationally renowned performer and writer of the Muscogee Nation. She served three terms as the 23rd Poet Laureate of the United States from 2019-2022 and is winner of the Poetry Society of America’s 2024 Frost Medal, Yale’s 2023 Bollingen Prize for American Poetry, and was recently honored with a National Humanities Medal.

Cara Romero is a contemporary fine art photographer. An enrolled citizen of the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe in California, her art is shaped by a visceral approach to representing Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural memory, collective history, and lived experiences from a Native American female perspective. Along with her art career, Cara is the Executive Director of Bioneers.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Kenny Ausubel

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Associate Producer: Emily Harris

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Production Assistance and Program Engineer: Mika Anami

- This program features music by Joy Harjo and from Nagamo Publishing, the Indigenous-created music library.

This is an episode of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature series. Visit the radio and podcast homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station and how to subscribe to the podcast.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

Neil Harvey (Host): In this program, we drop in on a remarkable conversation between two world-renowned Native American women artists. National Poet Laureate and musician Joy Harjo riffs with distinguished fine art photographer Cara Romero. They discuss how life is art, and how they make their art to reflect the lived truths of their cultures and people.

This is “The Power of Art for Healing and Justice” with Joy Harjo and Cara Romero.

Cara Romero (CR): Wow. Another full house. Good afternoon, everybody, thank you for coming today. My name is Cara Romero. Welcome to the 18th annual Indigenous Forum. We’re on day two of our annual conference. I’m really excited to be here with you…

Host: In March 2025 during the annual Bioneers conference, Cara Romero – Executive Director of Bioneers and Co-Director of the Indigeneity Program – sat down with celebrated poet Joy Harjo for a conversation at the Indigenous Forum.

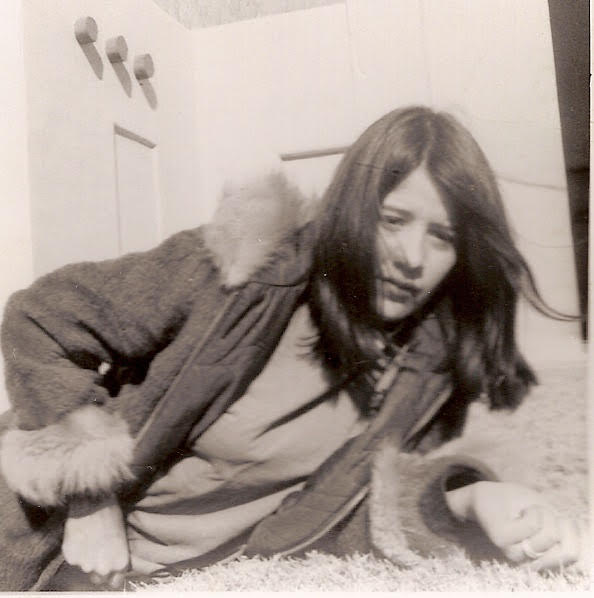

A musician and performer, Joy Harjo is a Muscogee Creek matriarch. She was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the heart of Muscogee Creek Nation. She comes from a people rich in tradition. They are language speakers, storytellers, singers, artists, preachers, dancers, and fierce protectors of their culture and community.

Joy came of age amid the 1960s backdrop of intense political and civil rights movements, including those for Native rights. Poetry became part of her artistic life amid this larger upheaval. She has received numerous awards and written eleven volumes of poetry, From 2019 through 2022, Joy served three terms as the 23rd United States Poet Laureate, She has been an inspiration for countless young Native artists.

Cara Romero is a contemporary fine art photographer. An enrolled citizen of the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe in California, Her art is shaped by a visceral approach to representing Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural memory, collective history, and lived experiences from a Native American female perspective. She uses contemporary photographic techniques to depict the modernity of Native peoples, illuminating Indigenous worldviews and aspects of supernaturalism in everyday life.

Here’s Cara Romero and Joy Harjo.

Cara Romero (CR): I wanted to talk to Joy today about what art has given to me, to my community, and what her art inspires us to think about and to be about.

I wanted to ask you about your earliest memories, about your childhood, about those memories that form us, that make us who we are later in life. And I know the stories of the Muscogee Creek people and how they made it to Oklahoma. Can you talk a little bit about your family’s history, about coming to Oklahoma, and maybe a little bit about what you were like as a young girl?

Joy Harjo (JH): Oh man…That’s a long story. Like where do we start? Because we started out in the Southeast, and were illegally removed by Andrew Jackson, who is—went against Congress, etc., to force us out. And my relatives stood up at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against that illegal move, but here we are in, now in Oklahoma. The Muscogee Creek Nation is now in Oklahoma.

And my father, my father’s Muscogee Creek, and we knew the story. We knew our relatives’ names. And that’s just always part of you. It’s not something that…I didn’t come from a stereotype. I came up in a family. There was cool stuff. My mother wrote songs and did demos for her music. And my dad, he was so good looking, and he loved to party. And we lived next door to the bootlegger. So we had some good times until they weren’t any good times.

But I grew up in a house of music. But also, really, I mean, now there’s a word for historical trauma. There wasn’t then. But, you know, there were those kinds of things happening too. But in the middle of it all, I knew I was loved, and I always had a kind of of compassion for my father and my mother.

And I think of my earliest memories, of course, is being a kid, and you realize—I mean, you think about your consciousness now, but when you’re a little child, your consciousness was still there. And as a child, I can remember being in that realm where I…It’s like the realm you go to when you create, or if you’re really good at fixing cars, and you’re listening to the engine and all that. It’s the same kind of realm. Or scientific study, or with a baby in your arms at 3 in the morning while you’re trying to rock them to sleep. It’s a similar kind of realm, where you’re in touch with things.

And I remember very early on that I preferred to be there sometimes, or outside. I wanted to be by myself, often. I always—I felt more myself by myself. I was in the closet a lot. The closet was full of my art, as was the garage.

But we were laughing the other day about names and naming, and I said, well, I was so morose, but they named me Joy. I mean, I was funny. I cared about my mother so deeply. I would run her bath and I would do things to make her laugh. I was the trickster. I was always doing things to make people laugh that I’d get into trouble. I got into more trouble than any of my brothers and sisters, just because I would run—I was very creative. But I loved – art is where I found myself. We don’t really have words for art. I think it’s part of something everybody did. You’d sit at the table, people would be drawing, carving—it was all—knitting, whatever people did. It’s just all part of life, the art of life and the art of living.

CR: I think my very earliest memories are when our family relocated from Los Angeles. I was born in Redondo Beach in Los Angeles to interracial parents. My dad is Native. My mom is non-Native. And our tribe had reorganized in the heart of the Mojave Desert, and my whole family moved back—my grandparents, my aunts and uncles, my mom and dad, my brother and I. We all lived in one trailer at the end of a dirt road, which eventually became our first council house for our tribe.

And we had the most pristine, undeveloped shoreline on the California side of Lake Havasu, and it was just in its kind of new strange beginnings at an edge of—all of our ancestral homelands were under the water, and here we were moving back as a tribe after a time of great sadness. You know, everybody had left when they flooded in the valley, and we moved back.

But I never thought of myself as an artist. It wasn’t something that we pursued as—like it wasn’t a pursuit. But I think back, as we get asked these questions a lot – when did you know you were an artist, or when did you become an artist. And I have to think back to these early memories and think, well, I was always an artist. You know? That was my best friend.

When there was chaos, when there was drinking, when there was trauma, when there—when you got sent to your room for getting in trouble, art was always there never asking anything from me. It was always just a place that I could go.

And so I drew. I drew for hours. You know, I grew up before cellphones and computers and all of that. And I think of those early childhood memories so fondly. And I think that they’re really important to who we become and how we form as young individuals.

Because, I think a lot of times we grew up out of place. You know, here we are like young Native kids in public school systems, and we live in these parallel worlds where it’s one way back home and then representation and academia or media or Hollywood is absurdly different. You know? Or what we read in textbooks about ourselves, or when we study cultural anthropology.

When I stumbled back into art, for me it was photography that changed my life. But I knew instantly that I was going to be able to tell stories through the art; that I wasn’t going to fit in writing textbooks or maybe being a Native studies professor, but it was actually through art.

Can you talk a little bit about the power that you felt when you became an artist to maybe do more for your community and for people than you ever imagined?

JH: I always felt like an artist, but I thought I was going to be a painter. Because I could go into that space, into that space, and listen and create, and so on.

And I was at the University of New Mexico, and part of KIVA Club, which was our Native student center and place where we could go and be with ourselves and be with each other. And we were—because of the times, I think it started as kind of a social club, but it became a place of awareness and issues, political gatherings and so on. We became very active.

And a lot of the political actions, Native rights movements were going on, and so on, and a lot of the surrounding Native communities, some of them would come to us because, well, we’re Native students at the university, so we must be smart in those kinds of ways, because that’s why a lot of us were sent there or were there, so we could go back to our communities with what we learned out there.

I remember going out to some of these meetings with uranium companies out near Laguna, or out in Navajo land who were dealing with the coal companies, and just sitting there and witnessing. I was a witness. And that’s where, for me, poet—my mother’s a song lyrics poetry and music, but listening to how these beautiful ways these people talked, sometimes in their own language, sometimes in English, that was very metaphorical in the way that I think all of used to use language.

I’ve heard language people in Muscogee, Hawaiian, and other Native languages say people don’t speak in metaphor like they used to, because when you use text, you usually don’t speak in metaphor. Well, what does metaphor do? It opens the space up from maybe two dimensional or three dimensional to maybe five or six dimensional. That’s the power of metaphor.

So I was listening to these people in the community make this connection with who they were as a people, and how they belonged to the land, and how they had been there, why they were there, and what their connection was. And they were standing there as guardians. Really, that’s really what got my writing started. I started writing poetry. But, I came to realize that what motivated me was healing and justice. Those became major motivators.

Poetry to me was similar to art in the sense that you were still, even in art, you’re dealing with rhythm, you’re dealing with color, you’re dealing with phrasing. It’s just—You know, and images in a certain way. I used to tell the artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I said you paint like a writer and I write like a painter. And that’s what started my poetry.

Which made no sense to anybody. How are you going to make a living? Poetry? And then nobody wanted to give you money—for scholarships—because poetry was not useful. You know? We need doctors. We need educators. But there was something, and what is that? There was something that was planted in me that I had to take care of.

It didn’t make logical sense. I’m a mother with two children, how are you going to make a living? But it was something I knew beyond knowing, and it gave me to create, and then to work with that. It’s very demanding. And nothing is given to you for free. I. I realize it was not about me at all. It was about what needed to come through on behalf of healing, on behalf of justice.

Host: After the break, Joy Harjo and Cara Romero explore whether making art is selfish or self-care, overcoming the steep barriers for women artists, the gift of mentors and ancestors, and the irreplaceable role that art plays in healing culture and history to honor future generations.

Host: Now, let’s return to Joy Harjo and Cara Romero in conversation at the Indigenous Forum, which took place at the Bioneers Conference…

CR: As you get older – I’m at the great in-between at almost 50 now, and I can look back and talk to my younger self and remember that the darkest times in my life were when I wasn’t creating, and the lessons that that gave me, that there’s some kind of self-sabotage that maybe we as Native people coming through trauma think I don’t deserve to have that happiness, or I don’t deserve to take care of myself.

And I think with art making, it can feel very…from the outside, frivolous. Or like you have this need to be selfish with time, but it’s actually for all of us, this radical act of self-care, to give yourself time to create.

And I think when we become mothers, it’s in our nature to sacrifice everything. Right? I think I learned that when I was making milk that my body would steal its own bone marrow to nourish my children, that this child was the most important thing. But that metaphor for me was like, you may also sacrifice your art making, or the things that keep you spiritually whole. And we have to problem solve as mothers, as art makers, like how can we look at this importance of spiritual health and creating, especially as women, to carve out that time for ourselves, and to give us that—It’s not selfish; it’s self-care. You know? And it actually makes your children healthier.

JH: Yeah, but there’s so much judgment for women who pursue an art. You have to walk through that. I remember I was so proud that I got an NEA grant, and I had just graduated from the University of Iowa, so I would be home working and people would say, well, because you’re not doing anything…[LAUGHTER]… Or even taking that time there’s been a judgment, well, you took that time away from your children. There’s a lot of that. A lot of it’s unspoken.

And women, we have to fight for our time and even place sometimes in the whole—in terms of being an artist, because there’s so much with our children. I love how you were talking about nursing and how you would do anything. It’s built in.

But, you know, our art’s also like that. It’s out of the same place of creating and giving birth and taking care of children. Art is, it’s the same thing, in a way, because you’re giving birth to something that comes through you, and you give birth to it, and you nurture it, and you grow it. It’s very similar to having children.

And there’s also—You were talking about self-care, and then I think also about culture-care, which is similar. When you’re doing your art, it’s not just about you.

And that’s how we know who we are as people, is our artists. And yet it’s so difficult to get funding for arts and artists, and Native arts and artists when—I was a founding board member of Native Arts and Cultures Foundation. But I remember we thought, okay, early on we have to raise money. Well, we’ll go to tribal nations and raise money. Yeah, think again. No one wanted to give money for art. “Well, what does that do for us? How does that help? We’re just trying to get by. You know, artists, they’re just selfish.” And yet I mean, how do we know our history? How do we know who we are, what makes us? It’s all about the arts and creativity.

CR: One of the things that we have to do as artists is we have to figure out how. And art is like this never-ending renewable resource, right? Like your creativity is never-ending. You know, it will always regenerate and it comes from something more than human. It comes from an incredibly special place.

So there have been times, as a mom, where I’m like I just can’t do this, but you have to figure out how. You have to drink coffee at night. You have to turn off the TV. You have to get a babysitter on the weekends. And for me, I didn’t know what I was doing at the time, other than being selfish, or that’s what it seemed like, but I was able to make art. That kept my spirit happy.

And in 2017, I got one of the grants from Native Arts and Cultures Foundation. That was how we met. I was so excited. They said we got to go to Minneapolis and I was going to get to meet Joy Harjo. She’s in that room over there. And I was just like a big fan girl. I wanted to tell you in seventh grade I played the saxophone.

JH: That’s cool.

CR: And that I knew she had gone to the Institute of American Indian Arts, and I had studied in Oklahoma. I was so excited to meet Joy Harjo.

But they gave me $25,000 to make art for a year, and I made more art than I had ever made in my life, and I made good art.

JH: You did, and you do!

CR: And it put me on the map. And you guys did more than that. You connected me with museums. And it was never a time in my life before I got that grant where they said you’re good enough; just go make it. Whatever your imagination can think of. And when you free artists to feel that they’re not frivolous or spending their electric bill money on creating dioramas or installations or things from their imagination, magic happens. Right?

And once it’s made, our society loves it, and centers these arts so much. But there’s a lot of us out there struggling, problem solving. And some of us, like my husband in particular, we can’t be anything else. And we’re often like the black sheep of the family. Right?

JH: Yeah, my brother and I decided we were the black sheep of the family.

CR: And I just say push through. You know? Like you have to continue pushing through, and being the artist, and that it will come.

I wanted to ask you about the Institute of American Indian Arts.

JH: Oh that place saved my life. When I went there, I think it was the late ‘60s. I think it started in about ‘64, and I was there ‘67. But it literally saved my life. I mean, I went from a house of music to a stepfather who essentially banned music. When it was his time to come in, my mother would stop singing, and she didn’t sing like she used to. And I was—I accidentally forgot what time—I was singing, and he came in and banned. He said there’s no singing in this house.

And so I tried to find a way out, and suicide was a possibility. And I heard about—I thought, I want to go to Indian school. I didn’t know about IAIA then. So my mother took me over, because I wouldn’t have lived if I had stayed there. And we went over to the agency, the BIA. But as we were going out the door, my mother said, oh, and she’s a really good artist. And the agent said, well wait a minute, there’s a new school here out in Santa Fe, Institute of American Indian Arts, and gave me the brochure. So I applied and I got in based on my art. And I was thrilled and went out there, and that changed everything.

I mean, you can imagine, I’d always thought of myself as an artist, and there I was with—It was—Then, it was eighth grade to twelfth grade and two years post-graduate, and young Native people all, and that’s when I thrived. Before, I would not talk in class. I didn’t engage much except with the friends I had. The Institute, that changed everything because I felt I was there in a place I belonged with all these young Native artists.

Then we had teachers like Fritz Scholder, Allan Houser, I mean all these incredible Native artists.

And you know, even though we were kids, we would sit and talk together about what art meant, and our art, and how it related. Even talking about sovereignty before there was a word sovereignty that was used as it is now. And we kind of knew that and there was something coming through us of that generation, that we knew that it was part of our, not just our survival, but thriving as Native people. And that generation was, I think, coming through at that time, really changed things.

CR: Within these abilities that we have to be artists is healing. And if there’s something that we need in our communities, and really with all peoples now, it’s healing. And we see art disappearing from our schools, and art disappearing from all the places where we desperately need it.

And I think it’s especially scary for me because I’ve always looked especially at Native arts as the things that carry educational bundles that exist against all odds. We were allowed to gather our shells. We were allowed to make our dance regalia. And we hid things. We hid knowledge. We hid traditional teachings in our art. And I think a lot of times when you go to see Native arts now, all of that power is still hidden.

It’s so important because art is disarming. You know? And everybody can bring their own experience to art. And it doesn’t ask anything of you. But if you can find a space where people, no matter their background, to think about things they’ve never thought about, or to have empathy for Native Peoples, or Afro-Indigenous artists, or Asian diaspora artists, or Latin artists, that is the power of art for social change.

That is the other beautiful thing about art is that it asks nothing of us. We don’t need those institutions to share and to embrace and to celebrate. I think the artists always during these times rise up.

JH: That’s true. We found our way through it before.

CR: And I guess you’re bringing up for me this idea of courage, and there’s a moment as artists where we find our voice. And sometimes it’s like—we’ll talk about finding our voice or finding maturity. For me, there was a few things that I felt a moment of liberation, liberation from the pressure of what people thought—liberation from expectations of the art world.

My grandmother, and there were elders in my life that inspired me, that gave me courage. And there were three of them that come up for me right away. My grandmother, when I would have moments of self-doubt, she said, “Oh Cara, you need to stop worrying so much about what other people think.” And it was just a moment where she was such a strong woman, and I never forgot that.

There was another moment where we were relearning our dances as I was much older. I was in my 30s. And this is something that we go through as Native people. Things were taken away, and there’s a certain humiliation that comes from relearning things at an older age when you’re not a little kid. And my friend, Wiletta[ph] Wilder taught me—she was from [INAUDIBLE] High[?]—and she said that as an older woman, she first started going to the dances, and the younger girls were teasing her. And she said never be afraid to dance; it’s between you and Creator. And that, for me, carried over into all of the art making. You know, we often talk that it comes from a place bigger than self, but never worry about what other people think, and you don’t have to worry about stereotypes or whether your art fits in, or what the world expects from you or where it’s going to go. Do it because you’re in communication with something much bigger than this world and yourself.

What gives you courage to be who you are and what you’ve given to the world? Are there people? Is there something that drives you?

JH: Well, I know what happens when I don’t. It’s true. You know? I’ve had a lot of teachers in terms of facing fears and stepping through. So I’ve had a lot of—I’ve had a lot of mentors. I’m not here by myself, necessarily.

I like what you were saying about the Creator in yourself. That relationship is prime, and that’s what art is, is that relationship and what comes out of that relationship, the shape of your life, what you’re doing, whether you’re an artist or not, comes down to that relationship. You know? There’s that presence always there.

And as a little kid, I remembered feeling that and feeling. We all have that child in us. That’s important to think of when you think of younger people and little children. Their consciousness, it’s all there. They see what’s going on. They may not be at a certain point of intellectual comprehension or language comprehension, but their soul sees and knows, and that’s who we are. And all of that is within us. Even our elder selves, even as we’re a little kid, because there is no—Time works differently in that space. We’re who we are. At whatever age.

CR: Well, I just wanted to say thank you for taking those risks and being brave for all of us to see what’s possible. You have affected a lot of young Native women, and that’s a really special legacy to leave. And we honor you for being here. Can we get a round of applause for Joy Harjo?

JH: And Cara Romero!

Host: Joy Harjo and Cara Romero, “The Power of Art for Healing and Justice”