Research Technique Creates Striking Image of Sea Star Nervous System

Bioneers | Published: February 13, 2024 Restoring Ecosystems Article

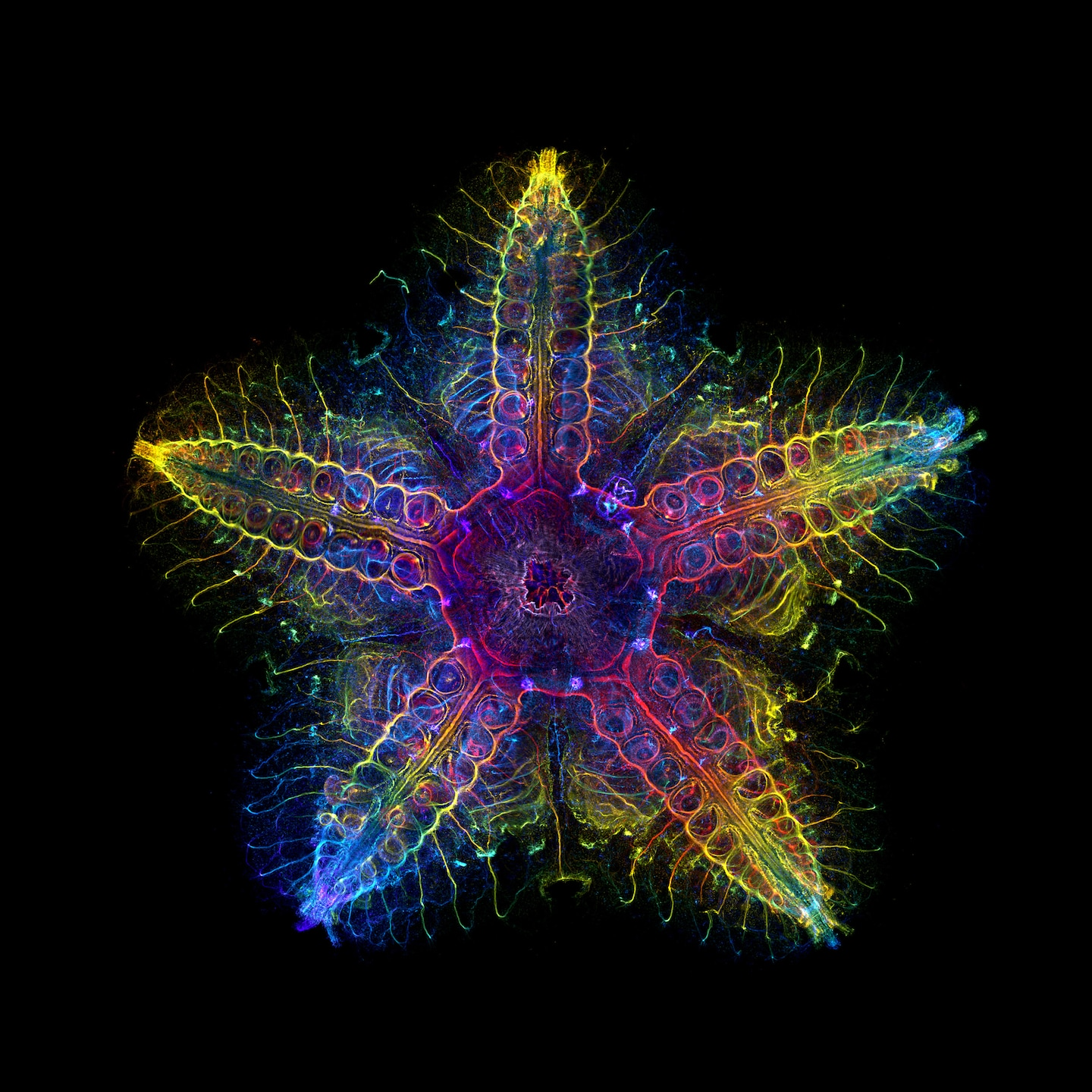

Though the beauty of a sea star’s nervous system was incidental to postdoctoral scholar Laurent Formery’s research on their development and evolution, its power is not lost on him. His microscopy image of a juvenile sea star’s nervous system is featured as a primary part of the composite image being used for the Bioneers 2024 Conference. The image won the 2022 Evident Global Scientific Light Microscopy Award and made the cover of “Nature” as part of his recently published study. In the image, each layer of the sea star’s nervous system is represented by a different color, resulting in an arresting rainbow-hued rendering of its internal workings. While the study that produced the image has its own compelling findings, Formery said that the attention-grabbing visuals produced by the microscopy process certainly benefit the research.

“Microscopy is fantastic for this because if you look at the Nikon Small World or the Olympus Microscopy Awards, there are so many absolutely gorgeous pictures,” Formery said. “I just appreciate microscopy a lot. I think you can do really interesting things. And, while it’s not necessary, of course, it is good to be able to make insightful science that also happens to be nice looking.”

In the following conversation, Formery speaks with Bioneers President Teo Grossman about the role beauty plays in his research on sea stars and other echinoderms.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

TEO GROSSMAN: What is your specific field of research?

LAURENT FORMERY: I’m a trained developmental biologist, so my overall approach is to understand how one cell can give rise to a complete organism that has three dimensions and all the complexity that comes with life. What I’m doing now really is more evolutionary biology, and so I would say my current research is really trying to understand how we have animals that look so different. What happened during evolution to make that possible?

There are two ways you can think about this problem. One way is to go look for fossils and try to reconstruct the story of evolution to understand how animal diversification happened. But you cannot do that for everything because there are a lot of animals that just don’t fossilize. For those cases, we turn to the lab and the field of molecular biology. We explore similarities and differences in related organisms at a genetic and molecular level for mechanisms such as how their bodies might develop from eggs, for example. By making these comparisons, we can begin to make inferences about the evolution of these animals in deep time. By conducting these types of analyses on a range of animals, you can progressively reconstruct the story of animal evolution. That’s important because that’s also telling us where we come from, basically. I’m focusing on a particular group of animals called the echinoderms, to which sea stars belong, together with other animals like sea urchins or sea cucumbers.

TEO: What are we actually seeing in the photo that Bioneers is using as the conference image this year?

LAURENT: You’re seeing the nervous system of a very small sea star that’s about one centimeter in width. So it’s a baby sea star. The species is a bat star, which is an orange sea star species that is very common on the West Coast. Most people assume that sea stars don’t have a very complicated nervous system and that they aren’t very complex animals. But actually, when you look at it, you realize that they have an incredibly complex nervous system.

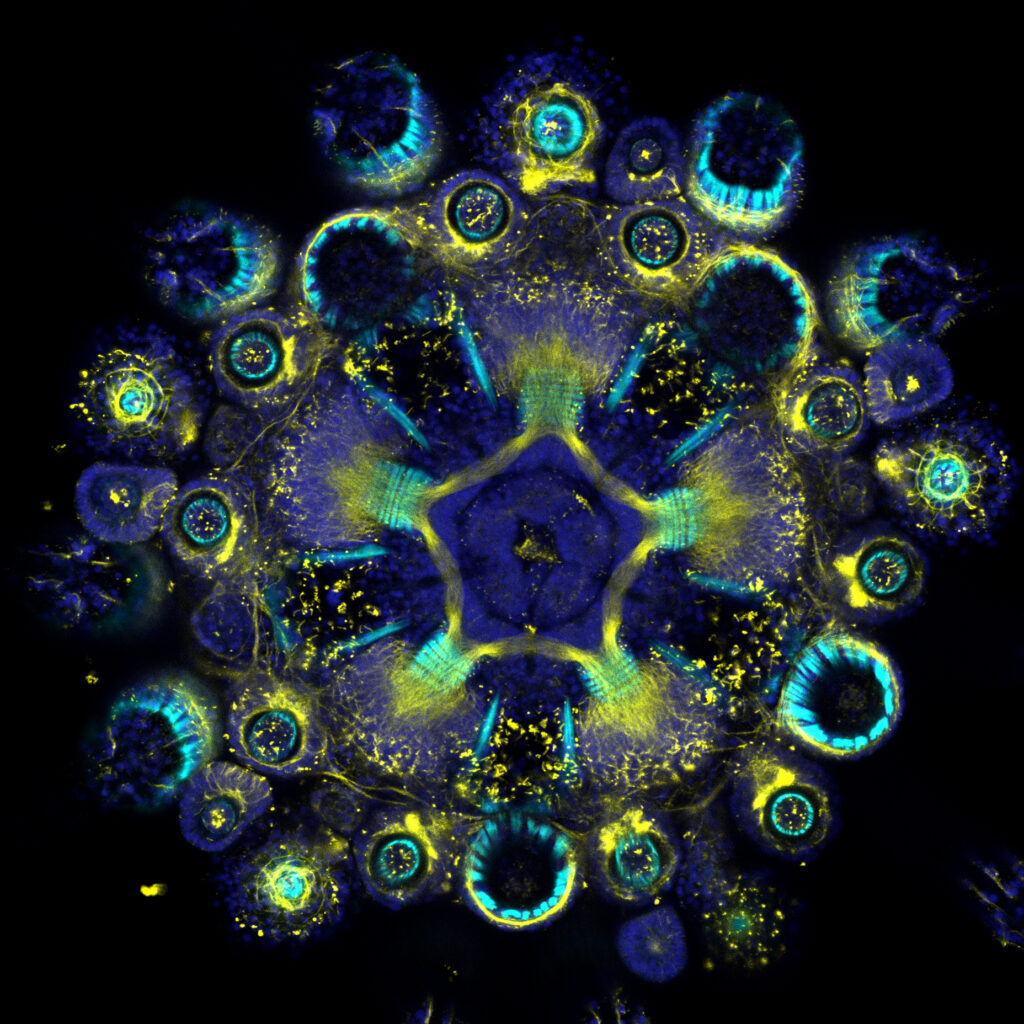

From a technical perspective, the image was made using a technique called immunostaining. We use antibodies that recognize a particular protein. In that case, the protein we target is involved in making neurons. These protein-recognizing antibodies are coupled to a fluorescent molecule that can be seen with a fluorescent microscope.

The challenge with that particular image is that sea stars are completely opaque and the microscope cannot see through opaque tissues. We had to develop a technique in the lab to make the tissue completely transparent, which was kind of a fun process, and that’s really what allowed us to make this type of image.

TEO: These are colors you introduced, is that correct? I’m wondering if they represent anything inherent in the organism?

LAURENT: Yes. The colors are completely artificial. The microscope that I use is a microscope that makes very thin layers of images that stack on top of each other. We can scan a number of these into a sample, creating a series of pictures, basically. In the end, what we get is a stack of images that can be visualized in 3D or we can merge everything together into a 2D image. What I did in this case is assign each of the layers its own color, so when they merge together, the result is this kind of rainbow feature. It’s showing you the distance or the depth of the information in your sample.

TEO: It’s like a topographic representation of the sea star.

LAURENT: Yes, exactly. I believe I think the red is close to you and the blue is far away from you. You’re looking at the sea star from the above.

TEO: So this is like an MRI machine, basically, taking slices and then reproducing a 3D image.

LAURENT: The idea is the same, but I think the MRI, you’re looking at tissue density versus here we’re just looking at a fluorescent molecule that we have introduced in the tissue.

TEO: Is this process of taking the images, restacking and coloring them part of the process of the research you do anyway, with the striking image a beautiful side result of the endeavor? Or are you up late playing with these images in your spare time, outside of the research objectives?

LAURENT: In my research, I spend a lot of time doing microscopy, and sometimes you just get very beautiful samples, when the shape is perfect, undamaged, and looks exactly as you’d like it to look. In these cases, I just do a longer acquisition to make a very beautiful image. So yes, it’s a side product of the research project.

TEO: Did you have to do any post-production in Photoshop afterward, or is this more or less how it came out?

LAURENT: It’s more or less what came out of the microscope, but I think I did change a little bit, like the color scale, in Photoshop.

TEO: In my time at Bioneers, I’ve talked to many scientists about the relationship between the actual research they are engaged in and their beliefs and feelings as a person. “Beauty” is not necessarily a scientific term nor a research goal but you’ve created this and many other truly beautiful and striking images in the course of your work as a scientist. I’m curious what you make of the relationship between the beauty of the imagery and the scientific goals of your research, the history of life on Earth, from single-celled organisms to the diversity of life on Earth today.

LAURENT: I think it’s not something every researcher appreciates, really, but I just find that the animals I’m working with are beautiful. I always try to do them justice somehow.

In terms of research, it really helps if you’re producing nice visuals because people are drawn to that. And microscopy is fantastic for this because if you look at the Nikon Small World or the Olympus Microscopy Awards, there are so many absolutely gorgeous pictures. I just appreciate microscopy a lot. I think you can do really interesting things. And, while it’s not necessary, of course, it is good to be able to make insightful science that also happens to be nice looking.

TEO: Laurent, part of what you’re doing in terms of the microscopy here is continuing and contributing to a long legacy of botanical drawing and natural history illustration.

LAURENT: That’s a compliment, so thank you. I really love all those botanical and zoological drawings. I have this giant book from Ernst Haeckel with all these drawings of microorganisms that are absolutely gorgeous. He was a controversial guy, but the drawings are just breathtaking.

TEO: Right. John Audubon has a similarly complicated legacy as an illustrator. The Bioneers Conference has utilized Ernst Haeckel’s drawings numerous times over the years.

Laurent, it’s been a pleasure talking with you. The images are so beautiful and striking, and we’re really honored to be using them as part of the 2024 Bioneers Conference.