The Director of New Leaders Initiative on What it Takes to Become a Young Activist

Mona Shomali is the Director of the New Leaders Initiative at Earth Island Institute. Each year the New Leaders Initiative selects six outstanding young environmental leaders and honors them with a Brower Youth Award named after legendary environmentalist David Brower. In addition to honoring and supporting young leaders, Mona is an artist who works with themes such as interracial intimacy and environmental issues. She is also the author of the recently published book Water Mamas. Shomali previously was a professor teaching courses on environmental justice, governance and policy; and indigenous rights in the Amazon at Pace University, The New School and New York University. Mona Shomali was interviewed by Arty Mangan of Bioneers.

ARTY MANGAN: As Director of the New Leaders Initiative, what inspires you?

MONA SHOMALI: I just gave a speech at the 26th Brower Youth Awards and talked about why I love my job. I get to suspend myself in a permanent state of believing what’s possible because I am working with youth who are not jaded yet by the realities that can crush dreams as we become adults. They are immersed in what is possible, what pathways can be taken, what frameworks that have not been seen before, what new structures are possible.

The New Leaders Initiative works with young environmental activists who are not just solo practitioners in a lab, but who inspire and lead other youth, and who are in the space where they’re looking for environmental solutions that maybe only youth can come up with.

ARTY: These are definitely challenging times for everyone but especially youth. You mentioned youth leaders “who are not jaded yet by the realities that can crush dreams as we become adults.” That is such an important perspective that youth are able to embody better than older people, and a perspective that the world desperately needs to overcome pessimism. What other characteristics do you see in young leaders that make them successful?

MONA: Vision. I don’t know if it’s taught or if you come into the world with it. Some people just have a vision, and they work towards manifesting it.

We had a winner this last year, Inaam Chattha, who won for his work around climate anxiety, creating a safe space for youth. He noticed people around him had climate anxiety, and he thought, “We are all dealing with climate anxiety. What if I create an organization that gets people together to share their climate anxiety and comfort one another. They can still be a part of the movement, but they will have support.” I loved his project because he had a vision, and he manifested it from top to bottom, he got other people invested. He did this while being in medical school.

These young leaders have personal lives to deal with. When considering someone for a Brower Youth Award, we like to see that they are an active member of society contributing in a way that is challenging.

For example, if we see someone from a red state that is hostile toward environmental protection policies, and the BYA candidate is fighting and trying to pass resolutions and bills in the legislature, that’s the kind of person we’re looking for. They are overcoming serious barriers, which goes back to being a visionary. They need a vision to work through the barriers. That is a characteristic of many of the winners.

ARTY: Interesting that you mentioned overcoming barriers. I looked back over the last nine years or so of the Brower Youth Awards winners, and found that almost 70 percent are people of color. I have to be careful not to generalize, but in my work also, I’ve been noticing a strong emergence of youth of color who are stepping up as leaders, despite the extra challenges that they typically have.

MONA: I see that as a trend also. The Brower Youth Awards reflect trends in the environmental movement. And right now, I believe that there is a trend of people of color joining the movement in a way that wasn’t the case when I was an environmental studies major in 1997 at UC Santa Cruz.

Then it was pretty much exclusively a white department. We had one Mexican-American, there was one other Iranian-American besides me, and that was it; everyone else was white.

Because of urban issues coming into the fold, such as clean water, clean air, and because the movement is encompassing more than just conservation, yes, we’re seeing voices of youth of color emerging in leadership roles.

ARTY: You mentioned climate anxiety. It must be so difficult for a young person to visualize a positive future in the face of the multiple crises happening in the world. Recently you brought together some of your former winners and did a retreat dealing with climate anxiety. What came up during that time?

MONA: The person who led the workshop was a therapist. One of the things that she imparted on us was that climate anxiety, like any other anxiety, has to be dealt with as anxiety. She had a lot of methods and techniques that were clinical that I won’t do justice getting into. But from the youth I’ve spoken to who have less climate anxiety, they are the ones who are not tackling “the world.” They’re tackling their community, their neighborhood, their street, their local watershed. I think those folks are able, not to completely overcome, but to mitigate climate anxiety with local action. Otherwise it is overwhelming. If you look at world climate events, it’s really daunting. So, I think it’s good to make the aperture smaller and just think about what you can do locally where you live. You can get bigger from there, but I think starting where you are in the community you’re in is one way to not be as overwhelmed by anxiety.

ARTY: I work with the Bioneers Young Leaders Program, and that’s one of our themes. As a young person, if you look in any direction, the world needs help, so what are your passions and how can you use those passions to be an activist to help healing. And if you are able to find that path, then in spite of all the craziness that’s going on all around you, that will be your best opportunity to have a fulfilling life.

MONA: Yes. And I think you said something that I normally say when I talk to youth at the career days that I’m doing a UC Berkeley networking event with current students. When I’m in those environments, my advice is to get really good at something and then contribute that to the environmental movement. If you’re a really great accountant, become an accountant for an environmental group. If you’re a really great teacher, teach environmental policy or environmental studies. If you’re a really great litigator, become an environmental lawyer. If you’re really good with your hands, become a biologist and help with species conservation.

There’s really nothing that can’t help the environmental movement. I think what you’ve said that really resonates with me is find your passion, and get really good at it and then apply it to environmentalism.

ARTY: The multiple crises that we live with now is also the opportunity for people to plug in and become skillful, as you say, and help heal.

MONA: Yeah, I mean, we need everybody.

ARTY: Right. Another aspect of your work is the fellowship for UC Berkeley students. Who are those students and what do they do?

MONA: That’s actually one of my favorite parts of my job. I work with undergraduate and graduate UC Berkeley students who are interested in program management and research. They get real life experience working with a non-profit employer to produce a final project deliverable.

For example, starting in January, we will be doing a fellowship with law students for climate accountability, which is an Earth Island project. Six students have been selected and they will be researching fossil fuel companies and building a database, and tracking. I’m really looking forward to the project. It’s really exciting for me because I get to sit in and work with the client contacts.

In addition to the fellowship, we also do a poetry slam for environmental justice every year in collaboration with the Rhoades Foundation for communities and the environment. We usually have about 30 to 40 poets that come to us through Rhoades’ program called New Voices are Rising, which is an environmental justice fellowship. I teach a poetry workshop, and then we workshop poems and perform them on stage with a microphone and a DJ. The slam is a real party, and lots of people come.

ARTY: Earth Island Institute was founded by the legendary environmentalist David Brower, who among many other accomplishments, is credited with preventing the damming of the Grand Canyon. I have a couple of quotes from Brower that I would ask you to reflect on in any way you like. The first quote is: “I’m always impressed with what young people can do before older people tell them it’s impossible.”

MONA: As we age, we see more and more barriers and we start to shut down. Our dreams become dampened or less clear. When someone is young, if they can get encouragement, support and scaffolding, and foundational skills then I think it’s harder for their dreams to die.

ARTY: As an artist, how do you think people, as they age, prevent themselves from closing down?

MONA: It’s interesting that you ask that, because I actually think because I’m an artist, I never stopped believing in my dreams. I think artists can remain childlike in many ways. I have a few quotes. One of the quotes is: “Art moves the culture forward.” And “The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible.” So I think art is a part of pushing what’s new, what’s coming down the pipe, not being scared of it, embracing progression in society. I think art is about embracing change.

One thing I’ve noticed as I get older, some of my more serious friends are not as excited about change; they’re not as excited to try on a new hat, try on a new thought, try on a new paradigm shift. I’m so happy I have so many creative friends because I do think that sets us apart.

I think creativity is really central in keeping your dreams alive. Everyone can be creative. Creativity and keeping your dreams alive do go together.

ARTY: My last David Brower quote, and this is consistent with what we talked about in terms of understanding what your passion is and using that to heal the world and heal yourself, is: “Have fun saving the world or you’re just going to depress yourself.”

MONA: I actually struggle with the term “saving the world” because I do think sometimes that lends itself to a bit of Narcissism. I encourage my youth to make a paradigm shift. I think saving the world as a dream can be a little bit problematic. So I usually steer the youth away from that term because of some of the undercurrents of being the savior and saving.

I like to think that the Earth will self-correct, it just might self-correct in a way that is not inhabitable for humans. I don’t think we’re saving anything except our own species; I do think that the Earth has the power to self-correct.

ARTY: What about the part of having fun with your activism or you will become depressed? The statistics of young people, of their anxiety and depression and suicide rates are troubling.

MONA: Most of my friends have teenage kids, so I have a lot of teenagers in my life outside of my job. I think social media has created a lot of issues. There’s a lot of good that’s come out of social media, but I do think it is engineering a very isolated type of person. It’s very hard to have fun in isolation. I believe that social media is basically creating a new type of human, and that concerns me because sometimes when I see teens in a room, they’re not talking to each other, they’re all on their phones.

For leadership week, we bring together this year’s awardees before the Brower Youth Awards ceremony and do activities where we have to take the phone away. We go kayaking and we take the phones so that they don’t get wet. We do a ropes course and we take the phones so they don’t get caught up in the harness and the ropes. We look for activities that are naturally phone free because I’ve seen a lot of isolation from social media use. We jam pack those days with workshops and activities and hikes and meals and discussions. We also have an environmental action through a writing workshop taught by a woman who’s a four-time writer for an HBO series.

Muskan, a Brower Youth Award winner from a few years ago, said it was the best week of her life. This last year, Inaam said that it was one of the best weeks of his life. We have consistently good feedback about leadership week, so we pour more and more resources into it every year.

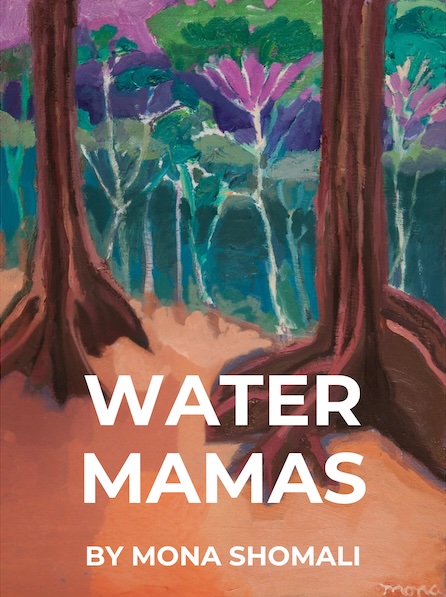

ARTY: Besides your work honoring and supporting youth leadership, you are an artist and, just recently, the author of a book.

MONA: The book, Water Mamas, is a work of climate fiction, but it is loosely based on my own work doing human rights advocacy in the Amazon. About 20 years ago, I was a case researcher on Sarayaku versus Ecuador. The Indigenous community of Sarayaku sued Ecuador in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for allowing illegal drilling on their land without free, prior and informed consent. After that, I continued to work in the Amazon.

After the Sarayaku, I worked with the Macushi on human rights. I taught a summer abroad program called Indigenous Human Rights in the Amazon. We learned, for example, about how eco-tourism can be a way for Indigenous communities to actualize their rights, their rights to resources, rights to having agency over their lives.

In the book I wanted to explore a tension that I had witnessed, which was environmental science versus Indigenous spirituality. I saw personally that Indigenous mythology was not environmental conservation, but rather it was following spiritual practices and laws that result in good ecosystem management. I wanted to write about how mythology leads to good ecosystem management and can go head-to-head with environmental science.

The book takes place in the not-so-distant future. The Amazon, the Earth’s lungs, are failing, and our lead protagonist is a UN representative who is trying to secure consent from Indigenous communities to start a rain seeding program, which does exist today. It’s used in California. The biggest program is in China. It’s a cloud technology that provides rain. But in the Amazon, there are human rights laws, so the protagonist has to get consent, and some of the tribes do not want to give consent because they fear the manmade rain will hurt their Water Mamas, which are the spirits that live in the forest. So they’re worried about their mythology and their spirituality. The story is a clash of worldviews, Western science versus Indigenous ancestral wisdom with the fate of global climate hanging in the balance.

I used to teach a course in which we talked about the role of culture and natural resource management. I talked about how science is an organized system of knowledge. Western science happens to be the most politically powerful, but there are other valid ways of knowing from cultures around the world. UNESCO, an arm of the UN, recognizes Indigenous knowledge and tries to record as much of it as they can.