To Be Seen by an Octopus: Sy Montgomery on Attention and Kinship

Bioneers | Published: January 21, 2026 MediaNature, Culture and SpiritRestoring Ecosystems Article

For much of modern history, humans have been taught to see other species at a distance — as resources, symbols, data points, or representatives of a category rather than as beings with inner lives. Science, religion, and culture have all played a role in reinforcing the idea that humans stand apart from the rest of the living world, uniquely endowed with intelligence, emotion, and agency.

And yet, across disciplines and traditions, that story has been unraveling during the last few decades. Advances in animal cognition and plant behavior research, long-term field observation, and new respect for traditional Indigenous ecological knowledge have revealed something both radical and deeply familiar: Other species think, feel, remember, communicate, and relate, often in ways that challenge our assumptions about what intelligence and empathy even look like. Learning to truly see them requires not mastery, but attention.

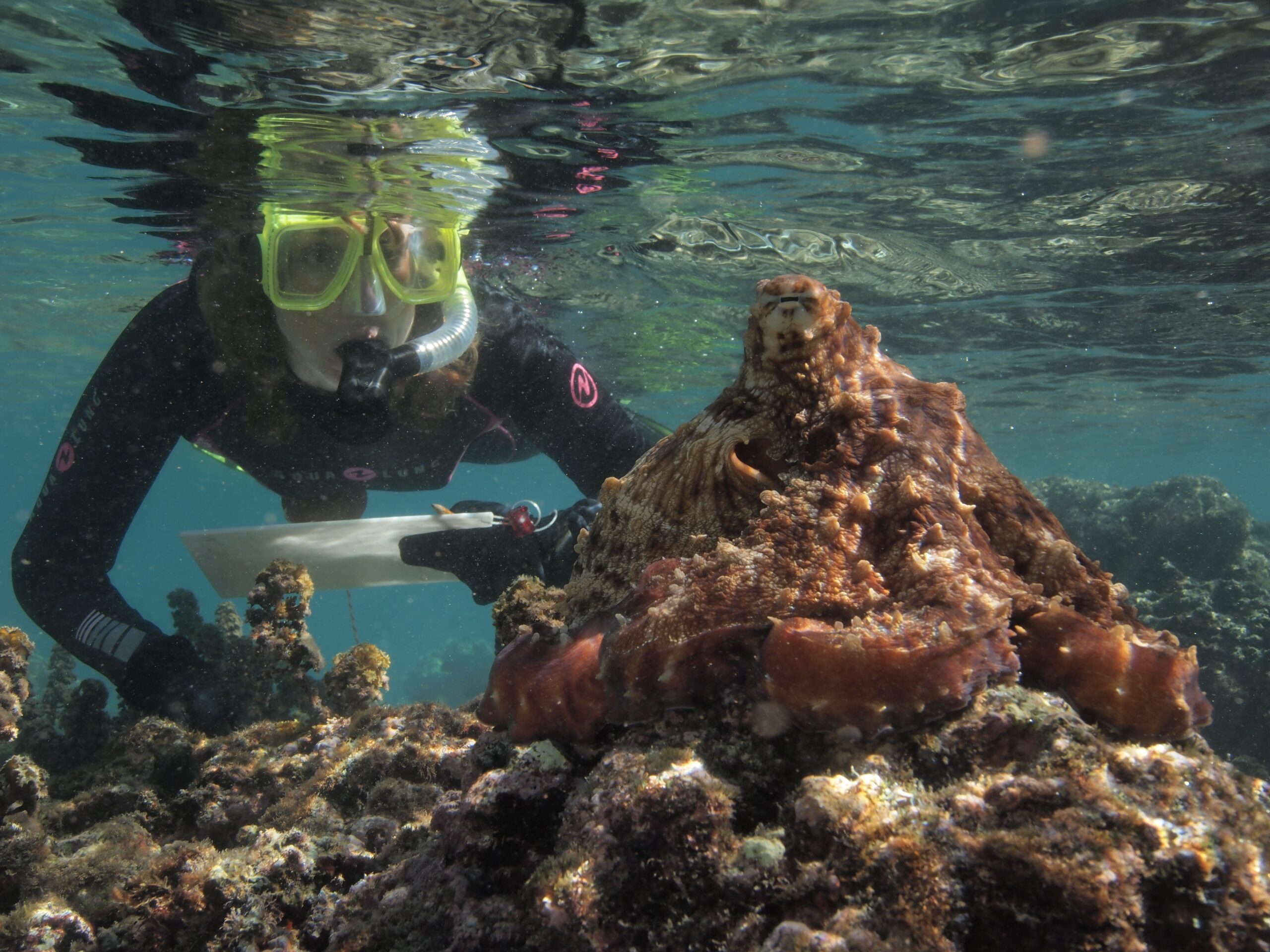

Sy Montgomery has spent decades practicing and writing about this kind of attentive relationship with other species. A naturalist and author of more than 40 books for adults and children, Montgomery has spent decades observing animals up close, from octopuses and turtles to pigs, dogs, and wild creatures encountered briefly in the field. Her work invites readers into relationships with other species not as abstractions, but as individuals, each with their own ways of being in the world.

In this conversation with Bioneers, Montgomery reflects on how humans lose — and can relearn — that way of seeing; what animals have taught her about empathy, identity, and attention; and why cultivating curiosity and care across species may be one of the most important practices of our time.

Bioneers: So much of your work invites readers to see animals as individuals, not abstractions. How did that way of seeing begin for you, and how has it evolved over time?

Sy Montgomery: I think most of us begin life seeing animals as individuals. As children, that comes naturally. But somewhere along the way, many adults lose that way of seeing. For a long time, science itself reinforced the idea that an animal was simply a representative of its species, not a unique being. Behavioral research used to treat animals that way, and frankly, I think the researchers themselves knew it was nonsense.

That began to change in a very visible way when Jane Goodall went into the field in 1960 and refused to number the chimpanzees she studied. She named them. She recognized immediately that each one had a distinct personality and history. Louis Leakey chose Goodall deliberately — she wasn’t trained as a scientist, and he wanted someone who might see something new. And she did. Today, especially in field biology, the first thing you’re taught is to figure out who’s who. Otherwise, nothing you observe will make sense.

In that regard, I don’t think I have changed very much since I was a child. I’ve always believed animals are individuals. What can be challenging is recognizing individuality in species that are very unlike us — reptiles, or marine invertebrates, for example. But once you pay attention, it becomes undeniable. Every octopus I’ve met has had a completely distinct personality. The same is true of turtles.

There’s nothing special about me in being able to see this. If I can do it, anyone can.

Bioneers: Why do you think we lose that way of seeing as adults? What do we gain — or lose — by that shift?

Sy: I think one reason is that it becomes much easier to experiment on animals, kill them, and eat them if we pretend they don’t have thoughts, feelings, or individual lives. There’s a real incentive to strip away individuality and dignity, because acknowledging it would demand responsibility.

A lot of this traces back to René Descartes and the idea that only humans think: I think, therefore I am. That notion flies in the face of both evolution and common sense. Evolution shows us that thinking, remembering, imagining the future, and feeling emotions all offer adaptive advantages. If loving your offspring or your mate helps a species survive, why would those capacities suddenly appear in only one species? That would be absurd.

Even the way we talk about evolution gets this wrong. We still call it a “theory,” though it’s long been proven fact. And evolution tells us we are connected — emotionally, cognitively, biologically. Our science says that. And so do our sacred stories. Every creation story, from every culture and religion, tells us that we are part of a family. We are related. We are similar. And we need one another.

When we forget that, when we deny kinship, we lose not just empathy for other species, but something essential about ourselves.

Bioneers: Have you ever encountered animals you thought didn’t show signs of empathy?

Sy Montgomery: Yes, but I think it’s important to remember that not seeing something doesn’t mean it isn’t there. It often just means we haven’t learned how to look yet.

For a long time, people used “bird brain” as an insult, assuming birds were stupid. What that really reflected was our own failure to recognize the complexity and power of a bird’s intelligence. Today, we know that birds like parrots and crows are extraordinarily smart. They make and use tools, plan for the future, and remember past events. Intelligence doesn’t have to look like ours to be real.

The same is true when we talk about empathy. When we don’t recognize it in an animal, it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist — it may just be expressed in a way we don’t yet understand. Size doesn’t tell us much, either. A small brain can be incredibly powerful, and intelligence can be organized in ways that challenge our assumptions altogether.

Take octopuses. Their brains don’t resemble human brains at all. You wouldn’t even recognize the structure as a brain if you were looking for something familiar. And yet they are astonishingly intelligent. Or consider sea urchins. They don’t have a brain in the way we define one, but increasingly scientists are suggesting that they are a brain — that their entire bodies process information in a distributed way, rather than in a single centralized organ.

These discoveries invite us to rethink what a “brain” even is, and what cognition can look like. Sea urchins don’t have eyes, yet they can perceive color, sometimes in ways we can’t. Octopuses can change color instantly to match their surroundings, even though they don’t have color receptors in their eyes. For years, people assumed they were colorblind. The truth was that we simply hadn’t figured out how they were seeing.

The lesson, again and again, is to keep looking. To stay curious.

Bioneers: Is there an animal encounter that truly surprised you? Something that defied your expectations?

Sy: My first encounter with Athena, a Giant Pacific octopus, in March of 2011 completely surprised me. I didn’t know what to expect, but one thing I did not expect was for her to seem clearly excited to see me … clearly curious. She looked me in the eye. She reached out and tried to touch me.

That moment knocked me off my feet.

Octopuses are so radically different from us. Half a billion years of evolution separate humans and octopuses. I didn’t expect to be able to read her at all. These are powerful, venomous animals, and yet I never felt fear. I also never felt aggression from her. Even when octopuses grab you, which they sometimes do, it has never felt threatening to me.

What surprised me most was realizing, in real time, that I could understand her intentions. I knew when she was curious. I knew when she was calm. I knew when she was engaged. And I hadn’t gone into that encounter expecting any of that. So I know I wasn’t projecting my own feelings onto her. I simply didn’t anticipate that kind of connection was possible.

To be seen, and to see in return, across such an immense evolutionary distance was thrilling. It changed my understanding of what relationships across species can look like.

Bioneers: Of all your immersive encounters, is there one animal experience that most changed how you understand yourself as a human?

Sy: I’m not sure I understand myself as a human at all. I didn’t really identify as human when I was a child—I thought I was a horse for a while. My pediatrician told my mother I’d grow out of it, and I did … when I realized I was actually a dog.

I joke about that, but there’s something sincere in it. Animals have always felt like my teachers. In How to Be a Good Creature, which is a memoir told through thirteen animals, I was forced to look closely at what each of those beings showed me about how to live. Animals are already perfect at being what they are. We’re the ones who struggle.

My first dog, Molly, taught me what I wanted to do with my life. She was my older sister, even though technically I was older. I wanted to go into the woods with her and learn how to understand the world the way wild animals do. In many ways, that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.

Other animals have taught me different lessons. Christopher Hogwood, our pig — who lived to be fourteen and died peacefully in his sleep — was a profound teacher. But it isn’t only the animals who live with us who shape us. Sometimes it’s a brief, unexpected encounter in the field that opens a door and changes how you see everything.

What animals have given me, above all, is a way to practice openness and compassion. Not just toward other species, but toward other humans as well. In a time when it’s easy to dismiss people who think differently as evil or stupid, animals invite us to do something harder: to try to understand another being on their own terms.

If you can stretch your imagination enough to consider the inner life of an octopus — an animal with nine brains that can taste and see with its skin — you learn how to put yourself into another way of being. It’s a kind of training in perspective-taking. And it’s a voyage I would recommend to anyone.

Bioneers: In your writing, you balance scientific rigor with deep emotional presence. How do you navigate that line?

Sy: I’m trained first as a journalist, and one of the earliest lessons you learn in journalism is to trust your reader. You don’t try to shove your opinion down someone’s throat. You show them what happened, and you let them come to their own understanding.

So I try to describe what the animal did, as clearly and accurately as I can. And I can also tell the reader how I felt when that animal did it. But I don’t want to draw the conclusion for them. I don’t want to force my feelings onto the reader. I want them with me on the journey and then arriving at their own meaning.

That approach requires restraint. It’s tempting, especially when you care deeply, to tell people what they should think. But I believe readers are far more powerful than that. If you trust them, they’ll often come to insights that are richer and more lasting than anything you could dictate.

My goal is to create the conditions for connection — to open a space where the reader can encounter another being, and then decide for themselves what that encounter means.

Bioneers: What feels most important to offer young readers right now, especially amid ecological uncertainty?

Sy: I don’t think of children as the leaders of tomorrow. I think they’re the leaders of today. Kids have an enormous influence, not just on their own futures, but on how their families live and even how they vote.

Years ago, a friend of mine who trained educators told me about a study showing that most conservation and environmental information reaching parents didn’t come from newspapers or the internet. It came from their kids. Children go home and say things like, “We shouldn’t kill possums; they eat ticks,” or “We need to stop using plastic bags because they hurt sea turtles.” Kids are powerful messengers.

They also have a natural affinity for the living world. Why wouldn’t they? Humans were hunter-gatherers until very recently, and paying attention to the natural world was once essential to survival. If we nurture that attentiveness instead of dismissing it, kids can become agents of real change.

Every child has some kind of power. Every child has something they love and some talent they can bring to it. What we need to offer them is the truth: knowledge is power, and love is power.

Bioneers: What do you think humans most misunderstand about other species or about our place among them?

Sy: I think we tend to fall into false binaries. Either we assume other species are so unlike us that they fall outside our sphere of care, or we expect them to be so much like us that when we notice a difference, we don’t know what to do with it.

I think the truth is far more interesting. We need to celebrate both our sameness and our difference. I love the ways I’m different from my dog. He can hear things I can’t hear, see in the dark, run faster than I ever could, and experience the world through scent in ways I can barely imagine. That’s a whole sensory universe I’ll never inhabit, and I find that thrilling.

At the same time, there are ways we clearly connect. He understands when I’m happy or sad. He loves affection. I love affection. That shared emotional ground matters, too.

It’s not so different from our relationships with other humans. You don’t want to spend your life in a hall of mirrors with people exactly like you. Difference is part of the joy. But neither do you want to be so alien to one another that connection becomes impossible.

When we approach other species with that mindset — curious, open, and willing to be surprised — relationship becomes a source of delight rather than domination. And that shift changes everything.