Urban Forests: A Nature-Based Solution to Climate Breakdown and Inequality

Bioneers | Published: November 1, 2024 Ecological DesignRestoring Ecosystems Podcasts

Visionary urban planners and community organizers recognize that effectively addressing the climate crisis requires drawing down carbon out of the atmosphere and sequestering it back where it belongs in natural systems. Urban forestry is a nature-based solution that simultaneously addresses the parallel crises of climate change and wealth inequality. With Brett KenCairn, Boulder city Senior Advisor and Samira Malone, Urban Forestry Program Manager at the Urban Sustainability Directors Network.

This is an episode of Nature’s Genius, a Bioneers podcast series exploring how the sentient symphony of life holds the solutions we need to balance human civilization with living systems. Visit the series page to learn more.

Featuring

Brett KenCairn is Boulder Colorado’s Senior Policy Advisor for Climate Action and Director of the Center for Regenerative Solutions (CRS)—an initiative to expand natural climate solutions nationally that is co-sponsored by the Urban Sustainability Directors Network.

Samira Malone is the National Urban Forestry Portfolio Lead at USDN managing an initiative at the forefront of urban forestry development. Previously, Samira served as the Executive Director of the Cleveland Tree Coalition.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Kenny Ausubel and Teo Grossman

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Production Assistance: Monica Lopez

- Graphic Designer: Megan Howe

This limited series was produced as part of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature radio and podcast series. Visit the homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

Host: In this program, we delve into how visionary urban planners and community organizers recognized that effectively addressing the climate crisis requires actually drawing down carbon out of the atmosphere and sequestering it back where it belongs in natural systems. Urban forestry is a nature-based solution that simultaneously addresses the parallel crises of climate change and wealth inequality. We hear from Brett KenCairn, Boulder city Senior Advisor and Samira Malone, Urban Forestry Program Manager at the Urban Sustainability Directors Network.

I’m Neil Harvey. This is “Urban Forests: A Nature-Based Solution to Climate Breakdown and Inequality”.

In the 1960s, NASA asked scientific researcher James Lovelock to design experiments for the Viking space mission to determine if there was ever life on Mars. He began to ponder what makes life different from non-life. Outer space brought him down to earth.

With the famed microbiologist Lynn Margulis, Lovelock proposed the Gaia hypothesis. It’s the idea that Earth is a kind of superorganism where the entire symphony of living things self-regulates Earth’s conditions to create a physical environment hospitable for the entire web of life. It’s also an ancient Indigenous perspective.

At this existential moment when humanity is destroying the conditions conducive to life on a global scale, what if the solutions to climate breakdown are hiding in plain sight in nature’s time-tested processes and principles that have allowed life to flourish and evolve for over 3.8 billion years?

That driving question led a small network of urban planners, public servants and community organizers to launch a visionary national initiative to scale up urban forests.

Brett KenCairn (BK): For many, many years – generations almost – of people who have lived in cities, if we’ve been aware of the urban forest at all, it’s just this kind of almost two-dimensional backdrop to the world that we’re living in, and oh, it’s so nice; there’s a few trees.

I think one of the emerging understandings is that we shouldn’t think about trees as trees individually. They are part of communities too. And they need a whole complement of community to be able to support the cascade of relationships that are all a part of how they process carbon, how they capture and store water, how they move nutrients not only within themselves but to others around them.

And so I think we’re starting to finally realize first that they’re a life-support infrastructure that provides critical water cleaning, air cleaning, shade and heat modulation, extreme weather event buffering. These are actually critical infrastructure.

Host: Brett KenCairn is Founding Director of Center for Regenerative Solutions, and Senior Manager for Nature-based Climate Solutions in the City of Boulder, Colorado.

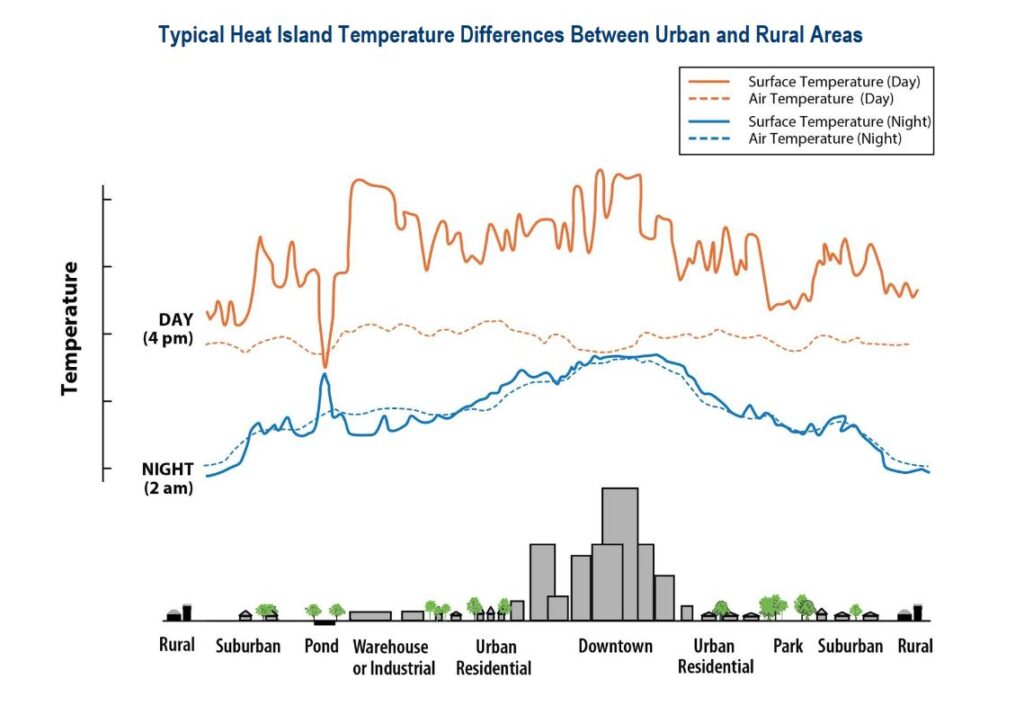

As global heating escalates radically, he suggests that urban forests are in fact “critical life-support infrastructure.” Cities experience what’s called the “heat island effect” as a result of paving over and covering most of the landscape. To offset this heat sink, mature tree canopies can cool the air temperature by up to 20 degrees, which can be the difference between life and death during a heatwave.

In addition to heat mitigation, increased tree canopy cover in cities leads to significant improvements in air quality, water quality, stormwater management, urban biodiversity, and outdoor recreation.

Expanding urban forests leads to major public health benefits, such as reductions in asthma and respiratory disease, as well as important improvements in mental health. Last, but certainly not least, trees sequester carbon from the atmosphere.

Here, the plot thickens. We’ve been breaking the kinds of records you don’t want to break: it’s the hottest it’s been in at least 125,000 years.

The summers are hotter in 84% of U.S. cities than ever before. In 2024, Phoenix, Arizona smashed all records with a broiling 113 straight days of temperatures over 100 degrees. Contact with pavement caused third-degree burns. The heat is moving beyond the boundaries of human survival.

Clearly, building urban climate resilience is imperative, but how?

BK: Climate change is fundamentally oriented around this issue of carbon, and carbon framed as the problem: CO2 goes into the atmosphere, it contributes to global warming. So the issue then is how we stop that. This is the classic smoking gun sort of causation slide, which is that the atmospheric CO2, around the late 1800s, as the Industrial Revolution is starting up, it starts to take off. And that seems to match quite perfectly to the increased use of fossil fuels. And so there you have it. See these curves? They match so beautifully, therefore, we have it here. This is the cause of climate change. It’s burning fossil fuels. And so CO2 is fundamentally that issue.

And so our solution is fundamentally a technological solution. So it’s the machines that we’re using to create energy that are burning fossil fuels, and so what we really need to do to solve climate change is just create a whole new set of machines. We just need more solar panels and we need more wind turbines, then we need more electric cars, and oh yes, we need some heat pumps. And if we do all that, we’ll solve climate change.

Well, I don’t know if you’ve been tracking the sort of science of this, but the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change came out about three years ago with their first kind of major bummer report, which said, remember what we were telling you about how we were going to solve climate change by reducing emissions? Well, all the things we were telling you to do, you need to do even faster, but it’s actually not going to be enough. We’ve now emitted too much CO2 and therefore, we’re going to have to ramp up the removal of CO2 if we’re going actually be able to stabilize climate.

So within that sort of context and our understanding that the way you solve climate change is build machines, then we just need to build a new set of machines. We’re going to build machines that suck carbon out of the air. And if you haven’t been following the news you’ll be hearing this more and more, like we have a machine for you. The problem is, it’s not working.

Host: Carbon itself isn’t the problem – the carbon element is the essential building block of all life.

The ground truth is that we’ve whacked the Earth’s regulatory systems wildly out of balance. Burning fossil fuels has shifted enormous quantities of carbon into the atmosphere from safely buried, otherwise harmless reserves of ancient plant matter.

But meanwhile, we’ve also been transforming landscapes across vast scales, releasing enormous amounts of carbon from soils and forests.

Scientists estimate that at least a third of the excess CO2 in the atmosphere is the result of removing these essential carbon sinks from natural life-support systems.

This radical transformation also coincides with the displacement of Indigenous and traditional peoples, who had been managing landscapes in mostly very sustainable ways for millennia.

A Gaian perspective calls for a whole-systems approach.

BK: Climate change is not happening because of some simple geochemical machine equation of CO2 in, CO2 out. The atmosphere is actually a biologically mediated dynamic – and it’s the extent to which we have degraded the living world that we have been disrupting climate. Yes, we’ve been tipping the balance because of fossil fuel combustion and we must change our energy systems, but it’s actually the regeneration of the living world that is the true hope of us being able to solve both climate change and a whole series of other existential challenges that we face. So let’s talk about what the foundation for a life-centered – not a technology-centered – solution to climate change might look like.

When we start to actually work with living systems, we can actually start to engage other hugely valuable and powerful cycles like the carbon cycle, the water cycle, the terrestrial energy cycle – and this is, by the way, why biodiversity is so important. Biodiversity is that integrator. We need all these different members of our community, who are not necessarily human, who all have very important jobs, to be integrating those cycles, and when that happens, remarkable and miraculous healing can take place. And oh by the way, we’re essential to that.

That all may sound like not such good news because that’s even bigger than what we were told we had to do, but we have done this before. We have regenerated landscapes at scale, in our own country in the ‘30s. The ecological catastrophe that the Dust Bowl represented is absolutely remarkable. It was huge. But we decided as a society that we were going to mobilize millions of people and we were going to put a significant amount of our resources towards it, and we were going to plant literally billions of trees, and we reversed what could have been an absolute ecological catastrophe.

Host: A majority of us now live in cities, and projections forecast that by 2050 urban centers will be home to more than two-thirds of humanity. In the US, urban dwellers are expected to comprise 90%. As climate disruption bears down, it’s the heat that kills and hospitalizes more people than any other extreme weather event.

In Boulder, where Brett KenCairn works in City government, the community sees itself as a laboratory for innovative policy making. As one of the first cities in the country with a sustainability department, Boulder recently reviewed its climate plans and came to the realization that they simply weren’t up to the job.

BK: Boulder was an early advocate for the kind of communities movement in climate action when the federal government, for example, didn’t sign onto the Kyoto Climate Accords internationally. Boulder said, well, we’re going to step forward and do it, and they were a part of a small cohort that rapidly grew of communities saying we’re going to sign onto these nation-level goals for emissions reduction.

Well, as it turns out, one of the things that we didn’t recognize at that time was, yes, fossil fuels and emissions reductions are an important part of stabilizing climate, but the climate scientists are now really clear, that’s not enough. Although, if you look out in the popular press right now, it still says that mantra. It’s like, oh, we just have to change our energy systems. Well, no, it’s not actually true, because as it turns out, the atmosphere is a biologically mediated dynamic. It’s not a geochemical machine that simply operates on CO2 in and CO2 out. It’s actually the byproduct of the respiratory process of the entire planet, and therefore, the fact that we have been degrading the living world for 12,000 years has actually contributed almost as much carbon into the atmosphere from that land degradation as burning fossil fuels, and it’s actually the mechanism that could have otherwise buffered all those changes.

So we started to realize that we really actually needed to take seriously that the living world was a critical part of our climate action strategy. So after a lot of, frankly, internal debate and trying to make the case, we actually formed a new climate action unit within our climate team around nature-based solutions. And now that’s a part of the work that we do, in addition to changing energy systems, in addition to circular economy work, we now have a nature-based climate solutions team. Our work in that team spans both urban landscapes and natural and working lands context.

Host: Given the reality of what a healthy urban forest can do to help mitigate public health and safety impacts from climate change, the real question is why every city isn’t already investing in this eminently do-able and sensible solution? More on that when we return.

I’m Neil Harvey. You’re listening to The Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature…

Host: Research has shown in many U.S. cities, a current map of healthy and thriving urban tree canopy almost precisely matches up with a map of wealth and income. Tree canopy cover in affluent neighborhoods generally ranges from 5-10 times more than coverage in historically marginalized communities.

Predictably, neighborhoods with the worst heat and least tree cover correspond with historical redlining. This long-term racist practice of underinvesting in communities of color and low-income communities by declining home loans has shaped and reinforced the social, physical and economic infrastructure of most American cities today.

But the heat is on and change is in the air. Enter Samira Malone, Urban Forestry Program Manager at the Urban Sustainability Directors Network.

Samira Malone (SM): The City of Cleveland has the largest percent of Black residents within the region. Cleveland itself has 33 distinct neighborhoods, and of those neighborhoods, as you guessed it, the Black and Brown neighborhoods have the lowest tree canopy. Although the City of Cleveland has a tree canopy percentage of 18%, it can vary between 6.5% to 30% across the various neighborhoods. And so one of the things that we do is we work very critically on the ground with those distinct neighborhoods to help them not only get funding to plant trees, but also thinking holistically about what inventorying and planning looks like.

So one of the things that I like to elevate when I talk about the work that we’re doing with trees, it’s not just about restorative and regenerative practices within our natural environment, but this really is an act of racial restorative justice because these are neighborhoods that have been disproportionately, historically disinvested in for decades.

Host: At its founding in 1796, the City of Cleveland had nearly 90% tree canopy. Its nickname was “The Forest City.” Now that the canopy has shrunk to 18% and is very unequally distributed, addressing environmental justice is on the table. In her previous role as Director of the Cleveland Tree Coalition, Samira Malone and her team worked with a 52-member network of local community organizations to increase Cleveland’s tree canopy to 30% by 2040.

Although it’s way easier said than done, urban forestry got a huge boost in 2022 with national funding from the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, known as the IRA.

SM: Our organization not only functions as a coalition, but as I mentioned, we also provide funding to our partners in order for them to do any types of plantings. We’re looking to expand to maintenance and preservation, but as it stands right now, our organizations are planting anywhere between 2,000 to 5,000 trees in the ground per year on an annual basis, which is great, but we still have a significant way to go. In order for us to reach that very robust goal of 30% tree canopy by 2040, we need to be planting 28,000 trees in the ground per year. That doesn’t even take into account the work that we need to be doing in preservation and maintenance of our existing tree canopy.

So as you see, there’s still a lot of room to grow, but even in that, I’m extremely optimistic and hopeful because we are seeing a historic investment in urban forestry. So we’re really excited about being able to expand and scale up the model that we have in Cleveland.

Host: In fact, the game-changing federal investment didn’t happen out of the blue. Beginning in 2020, a small visionary group of city planners, public servants and environmental, climate and justice organizers had formed a coalition to advocate for a major investment in urban forestry as part of the nation’s investment in critical infrastructure.

Fast forward to 2023. Again, Brett KenCairn…

BK: To make a long story short, after a lot of work, about a billion and a half dollars in the Inflation Reduction Act was actually allocated towards urban forestry in the United States. That’s about 100 times more money than the federal government would typically have been putting into urban forestry. But that was actually corresponding to the sudden arising of extreme heat events that were happening all over the country over the last few years in which we suddenly started to realize, oh my god, these trees are actually really, really important to us. In fact, one of the most valuable assets we have in trying to temper these extreme events is urban forests.

So I think that there’s been this sudden sort of explosion of awareness about the importance of forests, but then as we’ve stepped back saying, oh gosh, these are really important, we’ve started to realize how underfunded they are, how little we actually know about them; we actually don’t have very good data systems in our cities about where we have trees and where we don’t, how they’re changing. And then the best management systems. So, for example, when we started to actually say, okay, yes, trees are actually important for trying to mitigate extreme heat, but how much? How specifically much can I get out of planting trees versus something else? Because of course, in cities with public budgets, it’s always a tradeoff. There literally hasn’t been any mechanism by which we could say: If we plant this number of trees in this location, we can achieve this kind of temperature reduction.

So those are the kinds of tools and resources that we’re building now in collaboration with this whole cohort that we’re calling the Vanguard Cities, of places that are really trying to take the lead, not only by the way in this sort of notion of the sort of technique of urban forestry, but in the how do we implement it in an equity-centered, community-based way.

Host: The Vanguard Cities movement was born out of an imperative to connect leaders in urban forestry across the country to demonstrate its myriad benefits, and to gather data as to what works and what’s really needed to address the magnitude of the crisis.

Vanguard Cities has steadily built out a network of leading practitioners from city governments, organizers from community organizations, and world-class researchers from institutions around the country.

A billion and half dollars sounds like a lot of money, but it’s not even a rounding error in massive federal budgets. It’s more like a long overdue down payment.

Nevertheless, this federal seed funding is making a game-changing difference to organizations like the Cleveland Tree Coalition and its goal to plant 30,000 trees annually. Where it becomes truly transformative is by centering equity and restorative justice for communities long suffering from the burdens of history, such as Cleveland.

SM: It’s a rust belt city. We’ve been experiencing significant economic decline over the last several decades, a decrease in our tax base, population decline. And so trees have experienced that disinvestment as well, and oftentimes in a lot of neighborhoods, a lot of those redlined neighborhoods have more of a negative relationship to trees because of the lack of maintenance and care and investment put in them. So a huge part of our work is not only the implementation and increasing equity, doing so intentionally, but also shifting public sentiment.

We can talk all day about the value of trees and environmental value of trees, the public health benefits of trees, the economic benefits of trees, the benefits are endless, but if we don’t tie that tangibly to how that relates to people’s sustainability of self, people are tasked with the responsibility of surviving every single day – if we’re not tying the work that we’re doing to how you feel sustained and then how your family can feel sustained, and then how your community can feel sustained, then we’re doing the work in vain.

Host: Regenerating urban forests has the capacity to revitalize communities and local economies. Yet how do we overcome the insidious trap of gentrification that follows when greening neighborhoods makes them targets for developers who force out the residents?

It’s complicated, says Brett KenCairn…

BK: I think this is one of these places where it’s easy to oversimplify things. If we go in and we plant trees in an under-resourced community, we actually have just imposed a liability on them that isn’t going to provide any significant benefit perhaps for a whole generation. And it has to be kept alive in order for it to be able to get to the place that it provides those benefits. If we just plant that tree and turn and walk away, then we’ve basically really done more harm than good, because the other thing that will happen is that tree will probably die, and then people will say, see, I told you; we shouldn’t have trusted them in the first place.

We have to acknowledge that this is a community effort, and that if we are really going to do this in a way that’s going to be effective, we have to engage communities from the outside. And that means we actually have to budget for the process of working with communities.

We had this conversation once with a prominent national organization around trees, and we said, “Well, how much do you think it costs to plant a tree?” So there’s a number. It’s like $323 per tree, and that’s like for the tree and for the planting crew and for the amendments. We said, “Well, what about for the community engagement and for the ongoing maintenance?” And, oh, and workforce development. “Oh, well, we’ll just double it.” So there was just no sense of what it truly costs.

Many of these communities now, are often also the places where development is looking for opportunities to expand. And so there are many instances in which historically under-served neighborhoods don’t want additional trees planted because they see it as the first step of gentrifying their neighborhoods and then losing the access and control of those neighborhoods to gentrification.

So I think that as we start to think about strategies to significantly expand urban forests, they have to go hand in hand with anti-displacement policies and strategies, and with these kinds of community development and economic development opportunities. Because the reality is there are a lot of opportunities in this regeneration of green infrastructure, but they don’t necessarily immediately flow to the places that they should go. So we need to think about and really demand that our policies and strategies for implementing these kinds of changes serve multiple objectives like that.

Host: For leading smaller Vanguard Cities such as Boulder and other larger ones including Cleveland, Portland, Chicago, Denver, Albuquerque and Philadelphia, urban forests are in fact a bridge to the larger goals of both reversing climate disruption through carbon drawdown using nature’s solutions, while creating equity for communities. We’re at an existential fork in the road, says Brett KenCairn.

BK: What we’re doing at this point in the historical process is really piloting. And we are working at a scale that’s maybe 1/50th, maybe 1/100th of what it has to be done at scale to be truly achieving these levels of community protection, community regeneration and revitalization. And the only way we’re going to go from this very important, exciting piloting scale to that level where it truly has the impact that it has to have is that we have to restructure and reprioritize what the economy values, because right now the economy values a whole bunch of things which are actually directly destructive to living systems. And even when we just stop that, there’s still many more resources needed for the workforce development, for the community preparation, for the maintenance and the ongoing work. This is decadal work that we have to do.

And that’s not just going to happen because the secret hand of the market comes in and makes it happen. It happens because markets operate on the basis of the rules that we create for them, and the rules that we have to create through public policy have to start saying investing in and sustaining living systems is now one of our most important priorities, and we’re going to structure it so that that’s where people make long-term asset building living wage livelihoods.

We are on the cusp of spending hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars on technological solutions that won’t work, when what we should be doing is investing hundreds of billions of dollars into hundreds of millions of people in tens of thousands of communities, all over the planet, doing that land regeneration work, which if we do that, not only solves climate, but it solves a whole bunch of other related problems and makes our communities healthier. Gee, which one should we choose?

And it’s not exactly a complete this or that, but it’s certainly a lot more to this than it is to that.

Host: Brett KenCairn and Samira Malone… Urban Forests: A Nature-Based Solution to Climate Breakdown and Inequality.