Watching a Salamander Dance: Embracing Darkness to Observe Nocturnal Creatures

Bioneers | Published: June 25, 2025 Nature, Culture and SpiritRestoring Ecosystems Article

For billions of years, the natural cycle of day and night, light and darkness, has governed the lives of plants and animals. They have evolved with these cycles, which play a critical role in their survival. This daily cycle of light and dark governs life-sustaining behaviors such as reproduction, nourishment, sleep and protection from predators. But humans and our plethora of bright outdoor lighting are breaking through this vital darkness.

In “Night Magic: Adventures Among Glowworms, Moon Gardens, and Other Marvels of the Dark,” Leigh Ann Henion embraces darkness, rebuffing its associations with malady in the Western world. Henion writes that darkness is an integral and essential part of the human experience, and it’s one that we are collectively losing. She notes that organizations ranging from DarkSky International to the American Medical Association have implored the public to fight light pollution, which, in addition to degradation of entire ecosystems, has been shown to cause increased rates of diabetes, cancer and a variety of other ills in humans.

“What might we discover if we pause to consider what darkness offers?” Henion writes. “What might happen if we, as a species, stopped battling darkness—negatively pummeled in popular culture and even the nuance of language—as something to be conquered and, instead, started working with it, in partnership.”

Like many nocturnal creatures, salamanders’ natural activities can be confused or deterred by artificial light, including their mating rituals. As Henion explains, salamanders spend most of their lives underground, but once a year, they emerge to mate, navigating back to the ephemeral spring pools of their own beginnings to lay their eggs where fish cannot eat them. One such place is Barbwire Pond. In the following excerpt from “Night Magic,” Henion embarks with her friend Wendy to this ephemeral pool, hoping to see a spotted salamander dance.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from “Night Magic: Adventures Among Glowworms, Moon Gardens, and Other Marvels of the Dark” by Leigh Ann Henion, published by Algonquin Books, 2024.

Watching a Salamander Dance

Before I started spending time with salamanders, I’d never considered that it might be easier to slide across rain-glazed ground. I hadn’t thought about how moisture turns hard-edged leaves into tissue paper. I’d never looked up at bright clouds on a warm spring day and wished they would swell into dark forms. But that’s what happens the following day. Every hour of sunshine makes me think to myself: I wish it would just rain already!

When I tell Wendy that I’m headed out again that night even though clouds have failed to gather and temperatures seem below ideal, she offers to accompany me. Neither of us consider ourselves big news-watchers, but recent events have been acutely concerning. The specifics of doom are ever-changing. What remains the same is how scrolling newsfeeds makes me feel like my soul is shriveling.

My headlamp has, night after night, proven too diffuse for probing water. It is more of a bludgeoning device than a scalpel, so Wendy has brought her husband’s scuba light for me to borrow. I’m happy to have a better tool, but I’m having trouble figuring it out. The flashlight doesn’t have a switch; instead, its casing requires a twist. And I’ve twisted it too far, all the way to a distress setting that looks like the reflections of a disco ball. As the light thump-thumps against my calf, Wendy laughs. “How are you even doing that?” she asks.

The activity is so rare that some field biologists who’ve gone out for years have missed witnessing it. Still, I’m here because, against all odds, I want to watch a salamander dance.

The nightclub-style strobes inspire me to tell her that one of the reasons I’ve been excited to witness the migration is because I’ve heard that spotted salamanders perform artful courtship rituals. They nudge each other and move in circles. The activity is so rare that some field biologists who’ve gone out for years have missed witnessing it. Still, I’m here because, against all odds, I want to watch a salamander dance.

Wendy gets it. After a hard winter, she has specific natural-world yearnings of her own. “This time of year, I just want to get my hands dirty,” she says. “It’s the best way I know to combat the winter blues.”

It’s well documented that bacterium in soil can boost moods, maybe as effectively as antidepressant drugs. While light therapy plays a role in increasing serotonin and has long been used to combat seasonal affective disorder with morning exposure, researchers have started sounding warnings that being exposed to artificial light at night warrants more attention for its contribution to rising rates of mood disorders.

It’s been linked to pro-depressive behaviors, and it activates the part of the brain associated with disappointment and dissatisfaction. Brains that process artificial light at night are known to have lower dopamine production the following morning. But, given our cultural associations, it’s difficult to align with the concept of light as a force with the power to make us sad. We almost always use darkness to symbolize depression and light to indicate happiness.

The human relationship to artificial light is relatively new, but our relationship to natural darkness is ancient. This seems obvious, but it’s hard to absorb that, unlike society’s most prevalent light-dark metaphors, light is not always a positive force and darkness is not always a negative one.

It’s Friday, but there are no stadium lights tonight. The soccer fields are quiet. It hasn’t rained, and there’s nary a worm on the sidewalk. “I don’t think we’re going to see anything,” Wendy says, directing our attention across the New River, where security lights reveal the contour of a distant riverbank.

Instinctively, we turn to identifying the lights as if they are stars forming constellations. There’s a car dealership. A produce-distribution center. A new indoor gym that Wendy sighs at on sight. “That’s right on the river, one of the prettiest places in the world, and they didn’t put a single window on the backside of that building,” she says. Even in full daylight, people on treadmills cannot see the river running alongside them.

Outdoor lighting at night often gives people a sense of security, but there is not clear scientific evidence that it increases safety.

We recognize another cluster of lights as a gas station. We’re temporarily stumped by a parking lot that appears to be the brightest spot in the lineup. It’s directly across from the ephemeral pool. Ultimately, Wendy identifies the lot as being attached to the administrative offices of a local electric company. She shrugs. “I guess they were like, ‘Well, we’ve got the energy, might as well use it!’”

Outdoor lighting at night often gives people a sense of security, but there is not clear scientific evidence that it increases safety. In fact, some studies have found that streetlights do not lessen accidents or crime. Certain forms of security lighting have even been found to decrease safety since they make potential victims and property that might be stolen or vandalized easier for perpetrators to visually target. It’s a fraught topic with no easy answers, but the fact remains: It’s not uncommon for outdoor lights to be installed haphazardly, favoring as much illumination as possible with little thought as to how darkness might situationally be of aid.

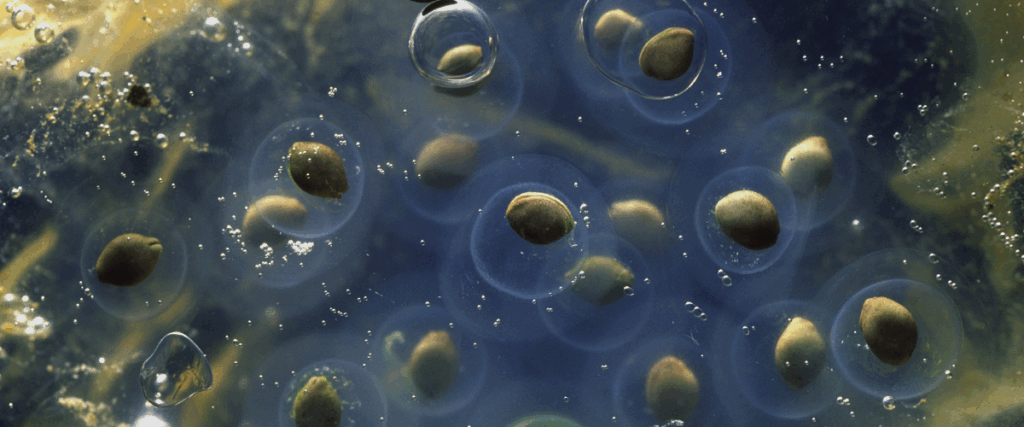

Temperatures keep dropping. Our breath appears as chalky puffs against a blackboard. We walk back toward the ephemeral pool, drawn by the promise of life. At the place where the sidewalk ends, we crouch in foliage that shields us from the lights across the river. In my scuba beam, I can see fallen twigs with salamander egg clutches attached to them. And there, in the middle of the pond, embracing one of those clutches, is a female spotted salamander. The egg mass she’s clinging to resembles NASA images of a star expanding. And right now, she’s adding to it.

“She’s laying eggs! Right now!” Wendy says. She grabs my arm in an I-can’t-believe-this move, and we jostle up and down like we’ve just won the lottery.

This isn’t the courtship ritual I’ve read about, in which males attempt to woo females by nuzzling their heads, but it’s clearly some type of dance.

Next to the egg-laying salamander, the pale flash of a second salamander’s belly appears. Then it disappears. This isn’t the courtship ritual I’ve read about, in which males attempt to woo females by nuzzling their heads, but it’s clearly some type of dance. “Did you see that?” I ask Wendy. But she is still hyper-focused on the egg laying.

“I can’t believe this is happening! We need to be careful that we don’t disturb her,” Wendy says, turning her scuba light from its high to low setting.

Meanwhile, two frogs locked in an embrace pop to the surface of Barbwire Pond. They’re surrounded by a halo of fairy shrimp who are fanning their pink-feather legs, flashing tropical colors in dark waters. Through the cloud of translucent fairies, the frogs swerve into a gelatinous mass of already-laid frog eggs, shining purple. Their movement is making everything quiver.

That’s when I see the dancing salamander again. From the darkest part of this pool, in the darkest part of this beloved park, the salamander’s star-dotted body shoots again to the surface of water. This time, Wendy sees him, too. “Oh, my!” she exclaims.

The animal is flipping. He’s somersaulting. His feet-hands are fervently waving back and forth, churning with such joy that we start laughing along with the wood frogs as, all around us, the peeper frogs howl. Every species in this ephemeral pool seems to have come alive at the same time. The water is writhing with life. It twists and turns, colors of a kaleidoscope, until I’ve lost my bearings.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from “Night Magic: Adventures Among Glowworms, Moon Gardens, and Other Marvels of the Dark” by Leigh Ann Henion, published by Algonquin Books, 2024.