‘We Ready Ourselves to Leap’: Community Resistance in Colombia’s Oil Wars

Bioneers | Published: May 23, 2025 IndigeneityJustice Article

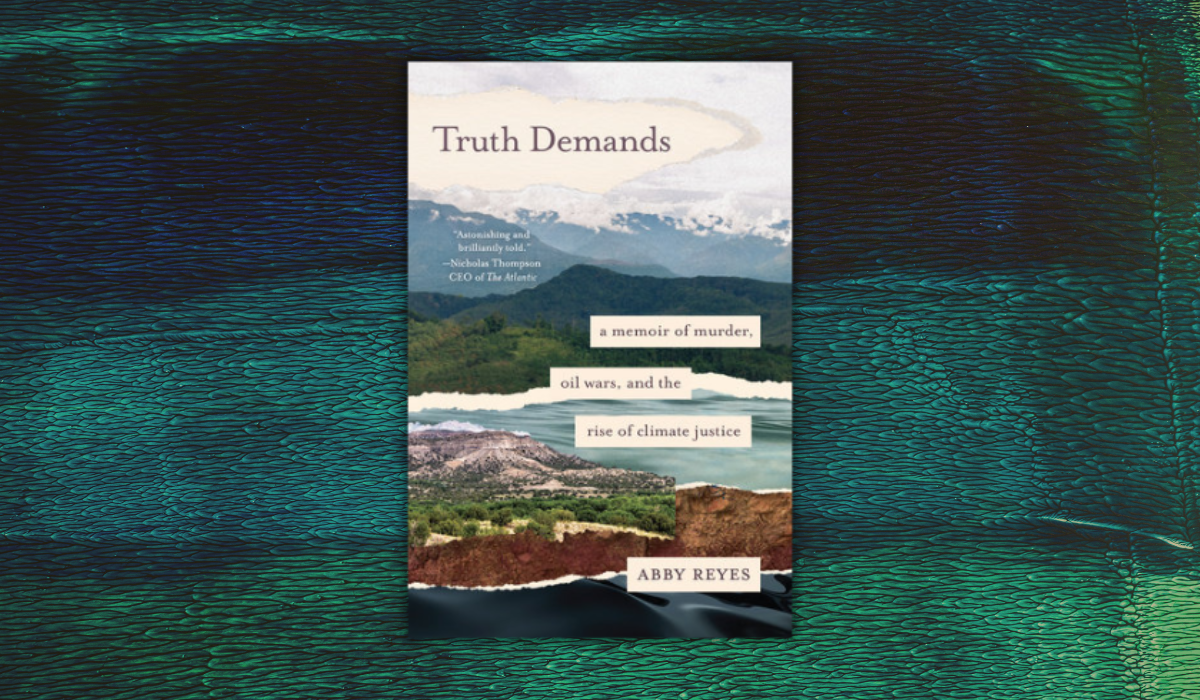

In 1999, Abby Reyes lost her partner, Terence Unity Freitas, who, along with Ingrid Washinawatok El-Issa (Menominee) and Lahe’ena’e Gay (Hawaiian), was murdered after leaving Indigenous U’wa territory in Colombia. Spanning three decades and three continents, “Truth Demands: A Memoir of Murder, Oil Wars, and the Rise of Climate Justice” charts Reyes’ journey as she navigates the waters of loss, purpose, and impermanence while fighting for truth and accountability from big oil. Today, Reyes is the Director of Community Resilience Projects at University of California, Irvine, where she supports leaders from climate-vulnerable communities and their academic partners to accelerate community-owned just transition solutions.

In the following excerpt from “Truth Demands,” Reyes reflects on the resistance to multinational oil interests in U’wa territory. Plus, check out this conversation with Reyes, in which she discusses land rights advocacy, entrenched oil interests, resistance and resilience, and what she hopes her book offers climate activists.

This excerpt has been reprinted with permission from “Truth Demands: A Memoir of Murder, Oil Wars, and the Rise of Climate Justice” by Abby Reyes, published by North Atlantic Books, 2025.

“Vuong observed that the word narrative comes from the Latin word gnarus, meaning knowledge. Stories then, even fragmented, can be the translation of knowledge and a transmission of energy. This energy cannot die.”

I am reminded of the story Terence told, writing from the cloud forest floor of the Colombian Andes. The story described the song cycle that his U’wa companions conducted to mark one U’wa girl’s transition into adulthood. Days of continual singing of the stories of their people, of how the rivers got their names. It was a song with no end. Some would pick up the song where others left off. And then eventually silence, within which the song reverberated for hours in the earthen floor. The reverberating stillness is not unlike the aftereffect of the monks and nuns chanting the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara’s name at Plum Village. Of the U’wa song cycle, Terence’s U’wa companion Daris later said that, while marking these life transitions, they sing about all the territory, including the rivers and mountains from Patagonia to Canada. She said the singing itself represents the equilibrium and sustainability of the planet. They sing so that people can remember who they are, right where they are, through the words, mountains, and waters that shaped them. So that the parable of the choir can persist. Terence wrote, “This is the reason we are doing this work, so that people can listen to singing.”

The U’wa say Terence, Ingrid, and Lahe’ “aren’t wandering in the river of the forgotten”; rather, their aka-kambra, or “word with spirit,” persists. After Vietnamese Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh died in 2022, Vietnamese American poet Ocean Vuong reminded the gathered and grieving community that language and sound are one of humanity’s oldest ways to transmit knowledge. Vuong observed that the word narrative comes from the Latin word gnarus, meaning knowledge. Stories then, even fragmented, can be the translation of knowledge and a transmission of energy. This energy cannot die. “In this way,” he said, “to speak is to survive, and to teach is to shepherd our ideas into the future, the text is a raft we can send forth for all later generations.”

The U’wa are known as the thinking people, the people who speak well. To speak well can take many forms. Whether the narrative is heard depends on the listener. In Terence’s notebooks from March 1998, he meditated on the voice of silence in the U’wa people’s resistance to oil extraction in their territory. “Where is the voice of silence? Of women? Of children? Of the communities that cannot speak publicly about opposition to petrol?” He wondered about the relationship between silence and fear. His final note regarded the silence of “the sound of the stumps cut during seismic line studies.” In U’wa territory, Terence contemplated the narrative that silence elicits.

Twenty years later, Colombia prohibited its post-civil war truth and recognition chamber from investigating the role of multinational fossil fuel extraction corporations during the internal conflict. In relegating corporations to third-party status, Colombia designed the chamber in a manner that restricted the range of stories that could be safely elicited. The narrative of silence was thus harder to hear. The sound of the stumps cut during seismic line studies did not ring out in the chamber. The earth itself was also rendered a third party, peripheral to the deliberations.

Out here on the shore, we know better. We know how to listen for the silence of the stumps and the parting song of the manatees. We know how to listen for the reverberation of the songs of belonging and for what Biago Diap would call “the ancestors’ breath in the voice of the waters.” The practice of listening sharpens our other senses. Our vision is clear: the truth demands we move these so-called third parties—both the corporations and the voice of the waters—out of the periphery and into the center of our vision.

And when we do, we look carefully. We heed the voice of the waters. We take note of the momentum in the water, and the timing. We remember that water flows around boulders. And that boulders get worn away. We take note of who stands gathered with us. We ready ourselves to leap.