We Will Fight Again: Defending Waorani Territory in the Face of Renewed Oil Threats

Bioneers | Published: October 2, 2024 IndigeneityRestoring Ecosystems Article

To the Bioneers community:

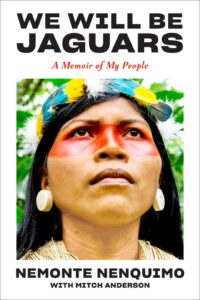

In November 2018, you received us and members of the Ceibo Alliance on the eve of a major battle we fought against the incursion of oil companies into Waorani territory in 2019. We won that battle, protecting a half million acres and setting a precedent to protect millions more, and we are grateful for your commitment then. Now, as we should only be celebrating the joy of our book release and sharing Nemonte’s story with you all, we are bracing to face the renewed threats to Indigenous territories across the Amazon.

Ecuador’s young banana scion president has made clear his intention to ignore the 2019 court ruling and auction off Indigenous territories in the Amazon to oil companies around the world. We will not stand back and watch this happen. We will fight again, and as long as it takes. We are again grateful to Bioneers for sharing an excerpt of our book here with you. We need to stay connected. What happens in the Amazon matters everywhere.

—Nemonte Nenquimo and Mitch Anderson

Excerpt from We Will Be Jaguars: The Oil Helicopter

We Will Be Jaguars is available here. Excerpt courtesy of Abrams Press.

My favorite days were those when Mom was too busy in the morning to notice us. It was on those days – when she was breastfeeding my newborn brother, Emontay, fanning the fire with turkey feathers, shooing the monkeys away from the meat smoking on the grill – that, instead of setting off for school, we would go into the woods with Dad.

Dad knew all the trails, and all the trails held stories. Sometimes, we would spend the day tracking a pack of peccary through morete palm swamps and over high hills. The swamps were easy tracking and we children were allowed to lead. But on the hard, dry ground of the hills, Dad took over. We always returned to the village with good things: baskets of fruits, game meat, palm leaves to make hammocks, cords of bitter lianas for hunting poisons.

On this morning, not very far from the village, we stood on a fallen log in a muddy stretch of forest at the foot of a canyon, staring at a lifeless giant anaconda. She had swallowed too much. Waited, flickered her tongue, lured the mesmerized deer close. Wrapped her and sucked her inside.

But the snake had made a terrible mistake. It had been lying in deep shade, where the mud was cool, when it took the deer. Maybe it was too young to know that it should slither into a sunny spot before eating a sinewy old deer. In the cold, Dad explained, the red brocket deer’s legs will straighten as it dies, and the colder the snake the stiffer the legs. This deer’s hooves had poked right through the snake’s muscles and burst open its shiny, oily skin. Her prey had killed her. Now she was surrounded by a maze of animal prints. Ocelots, pumas, anteaters, capybaras. A lone tortoise was gnawing at the rotting flesh.

“Look! A condor!” Víctor exclaimed, pointing up through the canopy.

“All the animals of the forest will come to pay their respects to the anaconda,” Dad said. “That condor has flown from the mountains, very far away, to pay tribute, to gorge on the powerful energy of the snake’s flesh.”

As I gazed into the sparkling light of the canopy, searching for little glimpses of the circling condor, I heard a faint whipping, chopping sound in the sky.

“Ebo, ebo, ebo!” I exclaimed.

Dad tilted his head, then lifted his hand, demanding silence.

“No, it’s not a plane,” he said. “It’s a helicopter. An oil company helicopter.”

When we got back to the village, my big brothers, Opi and Ñamé, were crouching with other kids in the shade of the helicopter, touching its big, bumblebee belly. Down the runway, villagers were milling about outside Rachel Saint’s house. Some of my friends, dressed in their blue and white school uniforms, were playing up in the branches of the miwagos. We followed Dad past the church and stood in the shade of a grapefruit tree.

“Cowori from the company have come!” Paa, one of the Waorani pastors, told us. “They are inside talking with Rachel and Dayuma.”

“Víctor, let’s crawl under the house,” I whispered.

I knew the entire floor plan of Rachel’s house. I knew where she slept, where she kept all the toys and the dresses and other gifts, where the sugar, rice, and noodles were stored. Sometimes we would sneak right under the room where she scribbled in her book as she whispered questions in a serious voice to Dayuma. Questions about the best way to say things in our language, Wao Tededo, things we had no words for: heaven and hell, sheep and oxen, forgiveness and faith. I knew that the scribbling sound was the sound of “God’s carvings,” the project they were working on together, but I didn’t understand what it meant.

We crawled on our knees on the damp earth. Through the slats in the floorboards I could see there were several white men now sitting around a table. They were laughing with Rachel in their own language. She looked very old and tired. She coughed a lot too. The white men were different from the other cowori that visited the village. They wore strange-looking hats – white, hard, and shiny – and orange uniforms.

Dayuma was sitting at the table, along with her husband, Komé. He had the biggest hands in the entire village and was always chasing us kids down and whipping us with stinging nettles for misbehaving. I was afraid of him. Both Dayuma and Komé were smiling and laughing, but I knew they couldn’t understand because they didn’t speak the cowori language. Dayuma had taught Rachel our language but Rachel had taught Dayuma only about God.

“How many of our men will go with the company?” Dayuma asked Rachel in Wao Tededo.

“Very many will go,” Rachel said.

“Will they go far away flying or will they be close walking?”

Rachel spoke with the white men and then turned to Dayuma. “If it goes well, then the men will go everywhere across the forest. Flying and walking.”

“Will they be gone long?” Dayuma asked. I knew she was asking so that she could report back to all the villagers.

“Many moons.”

Soon the cowori with the hard hats stepped out of Rachel’s house. Víctor and I scrambled away so no one would see us. Rachel pointed to the House of God, and to the school, and the men nodded.

Villagers were following them, asking questions.

“We are busy now,” Rachel said in a stern voice. “We will talk later.”

The white men carried black boxes with little handles. When they got to the helicopter, they shook Rachel’s hand and nodded their heads and looked right into each other’s eyes. Then they waved to all of us and said something that no one understood. The helicopter began to roar, making more wind than an ebo. I felt scared until I saw my older brothers, their arms outstretched, leaning into the wind and yelping with delight. I closed my eyes and leaned into the wind too. My hair blew in all directions. As the helicopter lifted off the ground, I saw my dad among the crowd. His mouth was wide open.

Amidst the storm and racket the helicopter made, a stillness came over me, a quiet aching thought: Those men are going to take my father away.

That night, there were no stars. A wet, cold draft blew into the oko. Dad was huddled by the fire, feet outstretched, toes wiggling just out of reach of the flames. Mom was kneeling over a pot of tortoise stew, squinting her eyes in the smoke.

“Your father must have eaten a lot of tortoise hearts when he was a little boy,” she said to all of us.

“That’s why he has no direction. Just like the tortoise, he goes wherever!”

She laughed. Her laughter was unkind. Only my brother Ñamé chuckled.

I didn’t like Mom being hard on Dad. He always took it though, staying silent, never rising to the bait. That made Mom even madder.

“Nemonte, did you know your dad was gone with the company for the entire time you were in my womb? He didn’t even let me know! He just got in the helicopter and was gone. He almost missed your birth.”

I was crouching in the corner of the oko, feeding bits of grilled plantain to our pet coatis, little creatures a bit like raccoons. Opi was sitting next to me, whittling a piece of balsa wood with Dad’s knife. I didn’t say anything. I didn’t want my parents to get into an argument.

“Dad, tell us about the Tagëiri and the Taromenane people that you saw when you were with the company,” said Ñamé. “Tell us about all the cowori they killed!”

I walked over to the fire and pulled out a piece of half-charred manioc. I knew by the way that Dad sat up in the hammock that he was going to tell a story now.

“When your mom was first pregnant with Nemonte, white men arrived in a helicopter. Just like today. They worked for the company. They talked with Rachel in her house. Rachel stood in the doorway and called my name, along with several others. She said: ‘Tiri, I need you to go with these men! Your uncontacted relatives are behaving badly. Over the last moon, they’ve spear-killed several company men. God wants you to go with the company and tell your relatives that killing is the devil’s work.’”

I chewed the manioc and leaned forward, watching Dad’s face in the firelight.

“I didn’t know how long I would be gone. I got in the helicopter with those men and we flew over the forest. I didn’t bring anything with me! I was barefoot and shirtless—”

Mom interrupted: “He left just like a hunting dog would! Following the cowori without a thought in the world.”

Dad muttered something under his breath and then continued: “When we got close to the Toroboro River, I saw the hills where we used to live when I was a boy. I saw peach palms that my grandpa had planted. We flew over a big road that went right through our old lands. There were many cowori living there now. They had cut down the forest, and there were cattle everywhere. Then we landed in the town of Coca.

“A man was waiting for us. He was the boss of the company. ‘Texaco,’ he kept saying. ‘Texaco.’ He gave us clothes and boots and hats and machetes and files. We were happy about that. We didn’t stay in Coca for very long. Although I wanted to see if the mighty warrior Nihua was buried there.”

“Nihua?” asked Opi. We knew the name from fireside stories. He was not our blood relative but he had close ties with our clan.

“The soldiers shot him and then cut off his head when I was a boy. That’s when all the trouble started within our clan. But there was no time to find out where he was buried; the helicopter soon took us away.

“We flew with the bearded boss into a small clearing in the forest. They called it a camp. There was a plastic tarp for shelter. The boss liked everything orderly. He barked instructions at the men. He said that anything we wanted must be given to us. We liked that very much.

“Then, before he left, he showed us pictures. In one picture, there were two spears crossed on the trail. We could tell they were the spears of the Tagëiri clan, our relatives who had decided to stay behind in the old lands, the ones who didn’t want anything to do with the white people. Their spears were just like ours. They were adorned with feathers of war, red macaw feathers. And little bits of red plastic that the Tagëiri must have found in the river.

“I think the boss wanted to know what it meant: two spears crossed on the trail. We didn’t say anything. Everyone should know what that means. Then he showed us pictures of a white man the company called ‘the cook.’ He had spears through his chest and neck. He was lying in the creek next to pots and pans that he had been washing.

“We didn’t know what we were supposed to do. The next morning, the workers started cutting down the forest. They had chainsaws. We had never seen anything like it! How fast they could cut through hardwoods! It would have taken days to cut through trees like those with a stone axe. We ventured off into the woods, but the chainsaws had scared all the animals away. That’s why the Tagëiri were unhappy. The cowori were making too much noise and scaring away all the animals.

“One night, while most men were sleeping, I heard the snapping of twigs on the forest floor. I stood up. I listened . . .”

Dad had walked over to crouch beside the fire but now he stood up, showing us how he had listened.

“I could sense that the Tagëiri were nearby. I told one of the cowori men to be quiet. But he got crazy-eyed. He walked to the edge of the forest and started shooting his pistol into the darkness. After that came silence.

“The next time I heard the Tagëiri, I didn’t tell anyone. It was daytime. They were making birdcalls to each other. I took several machetes and axes from the camp and walked into the woods. I called to my cousins and uncles: ‘I am Tiri, son of Piyemo, grandson of Nenkemo. We are living with the cowori now. We wear their clothes and eat their food. They do not kill us. I am leaving machetes and axes here for you. With these you will live well. You will make many gardens and have many children. I am Tiri, son of Piyemo. Who are you?’

“I knew they were there. I could hear them breathing. Later, I returned to the spot where I’d left the machetes and axes. They were gone.”

There was silence for a moment. Ñamé broke it.

“When I’m older, I’m going to go find the Tagëiri and live with them!” “Don’t talk nonsense!” Opi muttered. “They would spear you in a second.”

“Dad,” I said, “why were the cowori cutting down the forest?”

“We didn’t know why! They cut big trails. Straight lines in the forest. It didn’t matter if there was a huge tree in their way, or a morete swamp. They cut from dawn until dusk, and then fell hard asleep. They all smoked cigarettes and snored like peccary at night. The boss came back every couple of days. He brought orange cables, thick like lianas, and bundles of what they called dynamite. They made holes in the ground and dropped the bundles deep into the earth.”

“Will you go with the company again?” I asked.

“If he goes,” Mom said, “he’d better bring something back with him. Our kids don’t even have shoes for school, or a change of clothes. And look at our pots! Last time, your father was gone for seven moons and all he brought back was a bunch of stories!”

Dad didn’t say anything. He just looked down at his feet by the fire and wiggled his toes.

Nemonte Nenquimo is a Waorani woman, mother and climate leader, who has dedicated her life to the defense of Indigenous ancestral territory and cultural survival in the Amazon rainforest. She is the co-founder of the Indigenous-led nonprofit organization Ceibo Alliance and Amazon Frontlines. As the first female president of the Waorani organization of Pastaza province, Nemonte led her people to a historic legal victory against the Ecuadorian government, which protected over half a million acres of primary rainforest in the Amazon from oil drilling and set a precedent for Indigenous rights across the region. She is the winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize for Central and South America 2020 and was named a TIME 100 Most Influential People in the World in the same year.

Mitch Anderson is an environmental justice activist, human rights defender, writer, photographer, and father. He is the co-founder and Executive Director of Amazon Frontlines, a non-profit organization based in the Upper Amazon, which defends Indigenous peoples’ rights to land, life, and cultural survival. For nearly two decades, he has worked and lived in Central and South America, fighting alongside Indigenous peoples for clean water and the rights to their ancestral lands. In 2011, he moved to Ecuador’s northern Amazon to start a grassroots clean water project with Indigenous communities living downriver from contaminating oil operations. Through building more than 1,000 water systems in over 80 Indigenous villages, Mitch supported the founding of the Indigenous-led Ceibo Alliance that won the prestigious UN Equator Prize and whose victories for the Amazon.