What Carl Safina Learned from an Orphaned Screech Owl Named Alfie

Bioneers | Published: October 16, 2023 Nature, Culture and Spirit Article

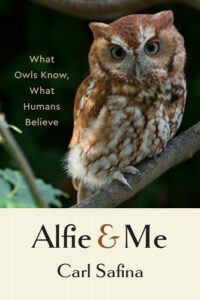

Carl Safina is one of the nation’s leading researchers on the natural world — as well as a passionate animal advocate — and a major figure in marine conservation. He is the inaugural holder of the endowed chair for nature and humanity at Stony Brook University on Long Island, N.Y., and the founding president of the not-for-profit Safina Center. He hosted the PBS series “Saving the Ocean,” writes widely for a variety of leading publications, and is the author of 10 books. Those include the classic “Song for the Blue Ocean,” the New York Times Bestseller “Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel,” and the 2020 New York Times Notable Book “Becoming Wild: How Animal Cultures Raise Families, Create Beauty, and Achieve Peace.” His latest book, “Alfie and Me: What Owls Know, What Humans Believe,” came out this month. His work, which fuses scientific understanding, emotional connection, and a moral call to action, has won various prizes, including MacArthur, Pew, Guggenheim, and National Science Foundation fellowships.

In the 1990s, Safina was a major figure in the campaign to overhaul fishing policies and restore ocean wildlife. He helped lead campaigns to ban high-seas driftnets, overhaul U.S. fisheries law, improve international management of fisheries targeting tuna and sharks, achieve passage of a United Nations global fisheries treaty, and reduce albatross and sea turtle drownings on commercial fishing lines. Along the way, he became a leading voice for conservation, widening his interests from what is at stake in the natural world to who is at stake among the non-human beings sharing this astonishing planet.

Below is an edited excerpt from an interview with Safina conducted by Bioneers Senior Producer J.P. Harpignies during the Bioneers Conference in Berkeley, Calif., in April 2023.

J.P.: Your first book was “Song for the Blue Ocean” back in the ‘90s, and you were one of the most influential activists on fisheries and ocean issues during some intense campaigns, including working to ban high-seas driftnets. You subsequently wrote a lot about marine mammals, but much of your work in recent years seems to be more about your love for the web of life and for animals. It’s been one of the main themes of your work for a long time, but I get the impression you’ve been delving into it more and more. Is that accurate?

CARL: Yeah, definitely. My first three books were about how people are changing the ocean and how those changes affect us and the creatures of the seas, but about 10 years ago I made a conscious inflection in my writing. Now it’s more about the human relationship with the rest of the world, and my last two books have gone even a bit beyond that. They’ve been about who we are here with on this planet. What are the mental, emotional and cultural capacities of all the other species that we are here with? It’s been a journey. I haven’t wanted to write the same book over and over again, so I’ve gone back to what was really my earliest interest, which is what other animals do and why do they do it.

My upcoming book, “Alfie and Me,” is also much more about the human relationship with the rest of life on Earth, why it’s the way it is for us now, and how it was in other cultures, in other times. And it’s really about what kind of relationship with the world we can have when we blur the usual boundary between us and other species. The narrative story is wrapped around a little baby screech owl that was near death that somebody found on their lawn and was brought to us, and whom we raised. She decided to stay around our property and to get a wild mate, and to raise young in a nest box that I put up on the outside wall of my studio.

When COVID erased my travel calendar completely, coincidentally, these owls were doing their thing in our backyard. With nowhere to go and nothing better to do, I watched them for about five or six hours a day, a few hours right around dawn and a few hours right around dusk. I saw nuances of their lives that are usually impossible to observe. I wouldn’t have had the time if it had been a normal year, so that was the silver lining in that year, when everything seemed to implode.

J.P.: Can you describe a little bit more about what it is that you observed that affected you and made you want to write a book about it?

CARL: Initially, I started taking notes not knowing at all where this might lead, whether she was going to survive. And if she survived, whether she would live to flying age. And if she flew, whether she would disappear or hang out around us. Best case scenario would have been she becomes healthy, gets a wild mate and they breed, and they raise young, who depart normally from the nest. It didn’t seem likely that would happen at the onset, but it did all happen, and I watched them all the way along. I used to be a professional field ornithologist. I studied birds for a living for about 10 years, and generally breeding seasons have several stages. There are courtship, incubation, chick-rearing, and fledging stages, but in this case, it wasn’t like that.

For one thing, this young owl had never had a mate before. She was raised by us, humans, so behavioral scientists would expect that because she imprinted on us, she wouldn’t develop normal owl behavior. But that wasn’t the case. She ultimately both reacted normally to a wild owl while still acting tame with us and orienting toward us the way she had been, but, after a while, orienting toward him in a normal way. Initially, because she was totally inexperienced, she didn’t respond in courtship. She was tentative with him at first, not really wanting to get too close. He started to offer her food, which is how owl courtship is supposed to go, but she didn’t take it right away. Eventually, she accepted the gifts, and they started to mate. She was awkward initially, but then she got it, and then they really behaved like newlyweds.

Then she laid an egg. And then she laid the other two eggs of her three-egg clutch, and the gears shifted again. It became much more of a settling down to business now — we’re going to have a family, the honeymoon is over. She was incubating while he was doing all the hunting. Then the chicks hatched, and she was doing the brooding. Then the chicks got bigger, and they fledged. The chicks at first went through a really dangerous transition where they wound up on the ground a lot because they didn’t really know how to maneuver. They’d fly to a tree and instead of aiming for a branch, they’d aim for the biggest thing they saw, which was a big clump of leaves. They’d try to land in the leaves and the leaves would give way, and they’d wind up on the ground. We have cats and hawks in the neighborhood that pose a danger. We watched the whole saga, and it was really magical and continues to be magical. She’s going to be five years old next month, and she’s still there. We still see her basically every day.

J.P.: She’s a multi-cultural owl.

CARL: Literally! And I say that in some of my talks about culture, because my last book was about culture. I show a picture of her, and I say she has a wing in our world and we have a foot in her world. She does things that have to do with being raised by us, like where she lives and how she responds to us. Her mate doesn’t do those things. It’s definitely a cultural thing. She’s a different kind of an owl.

For example, the young ones would normally leave the parents’ territory after a few weeks, but they hung around for a few weeks more while the parents continued to feed them. That was actually another totally fascinating thing. We think of young birds as always competing and the smallest one is going to be the runt that starves to death in the cutthroat competition, but it wasn’t like that at all. The parents were bringing so much food that the little ones were so stuffed that they would often move away from the parents while the parents were trying to offer food. And she just made sure that everybody was getting fed — and they all were always very well fed. They were never really hungry, those young ones.

J.P.: Interesting. And have you shared this with other ornithologists and compared notes and gotten surprised reactions?

CARL: A little bit. Not too much yet. The book will do all of that.

J.P.: Let’s delve into some larger issues about where you think humans fit in the web of life. Indigenous cultures tend not to view humans as radically different and “above” other species in the same way we have done in the Western tradition. Is that something you explore?

CARL: Yeah. That’s really what the book is about, other than the narrative story about the owls. It’s about the view we modern Westerners have of nature and where it comes from and how different cultures before us had quite different perspectives on the matter. I argue that there have been four main cultural approaches to viewing the human-nature relationship. One of them is that of Indigenous People who have a land-based identity and a deep sense of history with their land and their ancestors. Of course, there are many, many different Indigenous cultures with many different languages and customs, but nearly all of them, as far as I could tell, have very similar views that humans are part of a living world and not above any other part of that living world. Humans may have a bit of a special role to play in maintaining some of the balances, but everything is done with a sense of reverence and reciprocity toward the living and the material worlds.

If you want to use a plant or an animal, you have to express thanks and offer something in exchange. There are often ceremonies that have to precede cutting down a tree, for instance, and thanking the tree, or ceremonies that precede going hunting. And then, if you catch something, you have to thank that being and deal with the remains in ceremonial ways. You don’t just throw the bones away. There are proscribed things to do to show continued respect. Animals are viewed as having equivalent spirits to ours and often superior physical and spiritual powers. Certainly, many of them have better eyesight or hearing, or they’re stronger, or they can fly, or they can breathe under water. Things like that. We tend not to think of it as superior to us because we place human cognition on such a pedestal, but if a humanoid with a cape did something like that, we’d call that character a superhuman superhero. The kind of science that we practice in the West comes out of a tradition that overvalued human talents and thought that the Earth and other species were not worthy of any reverence.

J.P.: Hasn’t there been an evolution in scientific thinking about animals in recent decades? One hears much more about research on hitherto unrecognized animal cognitive abilities these days, and there’s more talk about “intelligence in nature” more broadly. Scientific gatekeepers kept having to move the goalposts. They used to say that animals don’t have language, but it turns out that some species clearly, irrefutably do. Then that they don’t have culture, but whales and chimps and many other species obviously, demonstrably do. They said only humans have tool-making, and that too was refuted. We obviously still have a long way to go, but where do you think we stand in this ideological battle? And do you view yourself on the frontlines of this emerging effort to finally break down science’s prejudices about our separation from the rest of nature?

CARL: Well, I view myself on the frontlines of trying to learn what I can learn. That’s about as much credit as I’ll give that. But it’s true that we know more than we ever knew before. Thankfully, we haven’t stopped learning new things. We know more than we ever knew before about the capacities of all the other minds that share the world with us, and a lot of that knowledge is extremely new. The first people who studied wild animals to learn how they live are almost all still alive and still working. Jane Goodall and Iain Douglas-Hamilton and people like that. It’s extremely new, and all the people we know and like are into changing their views based on absorbing new information. But it’s still a very small minority of the forces shaping the direction of the world. That’s why we’re in this “poly crisis,” as it’s now being called — the simultaneous climate, biodiversity, extinction, plastics and toxins crises, etc., all rapidly contributing to killing the world.

There are one-third fewer birds now than when I was in high school. And I live on the East Coast, where, in the fall, we’re right on the migration path. You can really see the difference. I can also really see the difference in some of the birds that were almost entirely wiped out by DDT and those other pesticides that have really come roaring back. It’s all very observable, but most species’ numbers are really way down. Yes, we’ve fixed a few things in the U.S. and a few other places in the world. The end of whaling has had a very noticeable effect on the number of whales that you see when you spend time on the oceans or on the coast, for example. But almost all animals are at their lowest population levels ever since the appearance of humans on this planet. And that’s entirely because 8 billion of us are occupying, destroying and polluting their habitats while temperature changes are decoupling animals from their food supply — insects from flowers, birds from insects, whales from food that they migrate to, etc.

There’s no way to sugarcoat it: It’s really a planetary catastrophe, but very few people really seem to understand just how catastrophic it is. Most people think that they’re doing OK or they want more than they have because they want to catch up with other people that they see. Or some people cannot wait for the world to end, because that’s what their religion tells them is where all of this should be headed.

J.P.: I get the impression that a lot of younger people do feel this sense of impending catastrophe.

CARL: Well, when I was in high school, a lot of these things were getting very obvious, and all the major environmental laws were basically passed in the ‘70s when I was in high school and in college. I thought at the time that our generation understood the situation and that we were going to fix things and set the world right again, but we absolutely failed.

J.P.: Well, some of us tried more than others. As a generation we failed, but I think that the committed activists in our generation can’t be blamed.

CARL: Well, look at the forces arrayed against us — all of the money in the world, just about literally, and the belief system that essentially backs the whole economy. The forces are overwhelming, and it shows.

J.P.: Yeah, we always knew that those forces were very powerful, but the degree of nihilism and cynicism of entrenched interests is just extraordinary. That said, they’re far from the lion’s share of human economic activity. There are quite a few impressive efforts at rewilding and regeneration of ecosystems in many different places.

CARL: Yeah. There are a lot of good examples, and some things are starting to turn around. And we also know how we could make a lot of things much better. The price of clean energy is starting to really make it economically the best choice, and the pace is accelerating.

J.P.: We’ve had a lot of coverage of that very issue at the conference these past few days.

CARL: Yeah, I have found this conference to be very refreshing, very uplifting, very inspiring. I certainly feel overstimulated. I want to go out and do lots of different kinds of things as soon as I get home.

J.P.: You’ve already done so much in your life, so I’ll be really curious to see what else you will accomplish, but I wanted to get to a deeper issue. Isn’t it, at its core, really a question of values, essentially, that you’re talking about?

CARL: It’s entirely a question of values. We need to draw from an ancient ethos. In prehistory, when humans achieved a certain level of consciousness, they looked around and saw the world as miraculous and humanity as sort of tenuous. And felt that if we didn’t respect the world that we belong to and that supports us that we might hurt it, so we needed to respect it. There are people regaining that sort of understanding, regaining it in a new way. Or maybe reinventing it based on current reality and a modern scientific understanding of things.

But, somehow, we have to go back to understanding that the world is a miracle and humans have a role in maintaining rather than hurting that miracle because if the miracle fails, we all go down with it. And it goes beyond that. We have to have simple justice for other living things. They don’t deserve to be annihilated. They don’t deserve to lose their footing in the world. They belong as much as we belong. Yes, if we destroy the world, we’ll all go extinct, but the wider world deserves not to be destroyed. We have no right to destroy this miracle that we don’t, so far, see any parallel to anywhere in the universe. Life is, at least, very, very rare, and it’s possible that this is the only place it’s happened.

J.P.: I think preserving the integrity and vitality of the biosphere is a sacred duty no matter what. But if this is the only place in the universe where sentient life emerged — which, despite all the speculation about other life far from our solar system, is all we know so far — that responsibility is crushing and enormous.

CARL: The basic religious feeling is the sense of being connected to something much bigger than you in space and in time. I am awestruck by the fact that I’m a very tiny, very brief little part of this thing that is so much bigger, that was here for so much longer and that will continue in some form. Maybe the best thing about people is that we have the capacity to understand something about where we actually come from and what we actually belong to.