David Orr | Democracy in a Hotter Time: Climate Change and Democratic Transformation

Democracy in a Hotter Time calls for reforming democratic institutions as a prerequisite for avoiding climate chaos and adapting governance to how Earth works as a physical system. To survive in the “long emergency” ahead, we must reform and strengthen democratic institutions, making them assets rather than liabilities. Edited by David Orr and rated one of Nature’s “best science picks,” this vital collection of essays proposes a new political order that will not only help humanity survive but also enable us to thrive in the transition to a post-fossil fuel world.

Purchase Democracy in a Hotter Time: Climate Change and Democratic Transformation here.

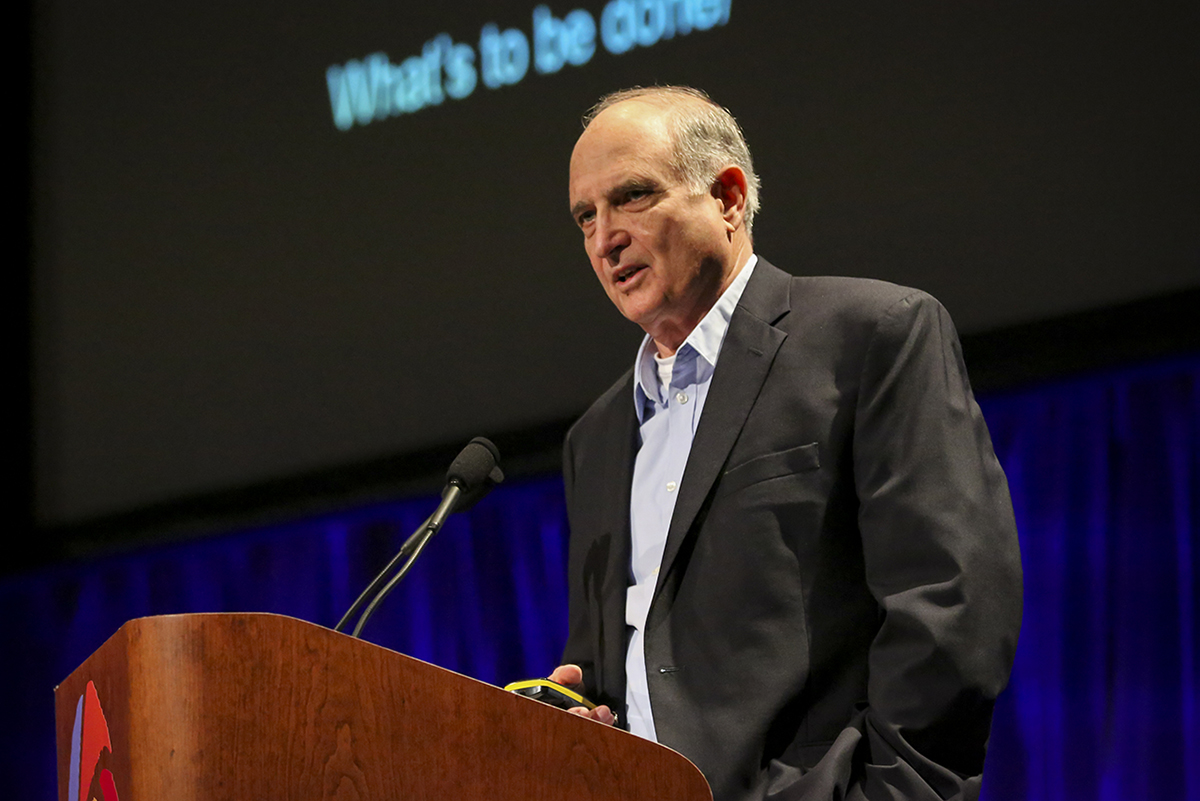

Introduction, by David Orr

In 1770, Tom Paine, thirty-three, was teaching school in Lewes, England; newly married Thomas Jefferson was building Monticello; and nineteen-year-old James Madison was a student at Princeton. The convergence of ideas, people, circumstance, and serendipity we call the American Revolution was still in the future. By 1800—thirty years later—these men had written some of the most brilliant reflections on government ever. The Colonies had declared their independence, won a war against the mightiest army in Europe, conceived a new constitutional order, launched a bold experiment in large-scale democracy, elected George Washington as the first president, and peacefully transferred power from one faction to another. Against all odds, they had imagined and launched the first modern democracy. Imperfect though it was, the fledgling nation had the capacity for self-repair evolving toward “a more perfect union.” Sojourner Truth, in that year of 1800, was three years old. Our challenge, similarly, requires us to begin the world anew, conceiving and building a fair, decent, and effective democracy, this time better fitted to a planet with an ecosphere.

This book is a scouting expedition to that possible future and a speculative inquiry about the transition to a more durable, fair, and resilient democracy, and what that will require of us. We are close either to a precipice or to a historic turning point, and for a brief time, the choice is ours to make. But let’s begin with where we are now.

In the summer of 2022, temperature in London reached 40°C (104°F); record heat, drought, and fire scorched 60 percent of Europe and much of China; New Delhi registered 45°C. Water levels in Lake Mead dropped to 27 percent of capacity and are still falling. The Great Salt Lake was shrinking fast. But much of Pakistan was flooded by unprecedented monsoon rains. The frequency and intensity of heat waves and heavy rainfall worldwide continued to increase. In dry regions, drought and wildfire intensified. The Greenland ice sheet melted faster than ever recorded. The century-long rise in global sea level was accelerating, and ocean temperatures continued to increase. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recorded 419 ppm CO2 in the atmosphere. Changing reality made it necessary to invent words like “pyrocumulonimbus” to describe never-before-seen things such as the massive columns of smoke and heat rising from western US fires into the stratosphere, creating their own weather systems below. All of this and more was happening with a global warming of 1.9°F (1.1°C) above the late-nineteenth-century average, exceeding the highest temperatures recorded in at least two thousand and possibly more than a hundred thousand years. Even assuming current policies to restrain emissions are fully implemented, we are heading toward a possible 5.4°F (3°C) rise by the end of the century, double the 1.5°C (2.7°F) red-line of “dangerous interference with the climate system” set at the UN Climate Change Conference, COP21, in 2015. After that, who knows. We do know, however, that at some point along the gradient of rising temperature, everything changes. First sporadically, as now, then as a constantly shifting “new normal,” and finally as a series of self-amplifying runaway cascades. There is no safe haven anywhere from effects of rising heat on ecosystems, societies, economies, political systems, and even our own health and morale. In Naomi Klein’s words, it is “an everything issue” unprecedented in its velocity, scale, and duration. It is also an everywhere issue. I wish—we all wish—it were otherwise, but it is not.

On the other hand, there are reasons to hope that long-overdue change is finally happening. In August, Congress passed the first major climate legislation in US history. The costs of renewable energy and improved efficiency continue to decline and are increasingly competitive with energy from fossil fuels and nuclear power almost everywhere. Sizeable majorities of the public support action on climate change and adoption of renewable energy. Business and finance are moving mostly in the right direction because the liabilities of “green” investments are lower and profits higher. Buildings and entire cities are being designed to be carbon neutral, driven by market demand, better technology, superior design, and more comprehensive building standards and international codes. And New York and two other states have amended their constitutions to include the right to “clean air and water and a healthful environment.” Whether all this is too little, too late, time will tell. Had we acted earlier, the hole we’ve dug would not be nearly so deep, but even after the first authoritative warnings decades ago, we kept digging. It did not have to be this way.

By the mid-1980s there was more than enough scientific evidence for the United States to lead a worldwide transition to energy efficiency, renewable energy, and ecologically smarter design of economies, cities, transportation, farms, and factories. We were warned, repeatedly, in ever greater detail, but did not act, committing “the greatest dereliction of civic responsibility in the history of the Republic.” In other words, we squandered whatever margin of safety we might once have had. Our failure to meet the challenge early on, when it would have been much easier, cannot be excused by a lack of technology or even by economics, since efficiency, renewable energy, and superior design have long been cheaper, faster, and more resilient than the alternatives and without the incalculable costs of climate chaos. The cause, rather, is political. Our fossil-fuel- and corporate-dominated democracy seems to have stalled out; our institutions corrupted by too much unaccountable money and elected officials with too much ambition and too little integrity; our various media by too much venom, too little concern for the common good. Now, in an ongoing right-wing insurrection, we are vexed and troubled, still struggling to solve even the most basic problems, includ-ing climate change, that threaten our own survival.

In short, we face two related existential crises: a global crisis of rapid climate change and potentially lethal threats to democracy. We believe these are related, and because people have an unalienable and hard-won right to choose how they are governed and to what ends, democracy is worth fighting for. We believe, further, that a more robust democracy would be a more effective, fair, and durable way to organize the transition to a post-fossil-fuel world than any possible alternative. And there’s the rub: democracy as it exists may not survive for long on a rapidly warming Earth, but on the other hand, as James Hansen says, “We cannot fix the climate until we first fix democracy.” Fixing democracy, however, requires fundamental improvements that, among other things, protect the written and unwritten rules that contain our political disputes and provide greater political equality, economic justice, and protection of the rights of future generations. It also requires improving government and governance by calibrating law, regulation, policy, taxation, administration, and behavior to how the Earth works, as a complex physical system with feedback loops and long gaps between causes and effects. Our predicament is compounded because some fraction of CO2 remains in the atmosphere for more than a millennium, rendering our plight a “long emergency” measured in the time required to stabilize the climate system and restore the Earth’s energy balance. Accordingly, we should study long-lived institutions, cultures, economies, and political systems for what we might learn about how to render our own more durable, decent, and fair over the long haul. Effective responses to both crises will require systems thinking, long time horizons, and the capacity to “solve for pattern.”

Rapid climate change, in short, “presents the most profound challenge ever to have confronted human social, political and economic systems.” As such, it is first and foremost a political and moral crisis, not one solely of technology or economics, as important as those obviously are.

The climate crisis comes at a particularly bad time. Authoritarianism is advancing here and elsewhere. Authoritarian governments sometimes move faster than democracies but have a dismal record on climate, environment, and human rights issues. Governments run solely by experts might possibly deploy technological and scientific expertise more surely than democracies, but they would have no monopoly on wisdom about wher and how to apply technology for what purpose, or when to stop. For these and many other reasons, we will bet on “we the people” and our collective capacity to strengthen, expand, and reinvent the institutions of democracy at all levels in the time available to meet new challenges posed by a warming climate. But it won’t be easy.

Novelist Amitav Ghosh puts it this way: “Climate change represents, in its very nature, an unresolvable problem for modern nations in terms of their biopolitical mission and the practices of governance that are associated with it.” Modern democracy, in particular, grew out of what historian Walter Prescott Webb once described as “the Great Frontier,” the opening of the Americas to European migration. The changed ratios of people to land, minerals, and forests for a time relieved demographic stress in an overcrowded Europe. The resulting affluence, he thought, made democracy possible by reducing scarcity and improving quality of life. Increased wealth sanded down some of our rougher edges, but the sheer rush of pell-mell capitalism also gave license for the genocide of Native peoples, slavery, Jim Crow laws, inequality, and ecological ruin. Our “biopolitics,” in other words, made climate change a predictable outcome of a system built on exploitation of people and nature alike and powered by fossil fuels. But as the ratio of natural resources to people becomes tighter, the struggles over the fair distribution of what’s left will become more bitter and eventually could be fatal to democracy.

Our predicament is rather like an engine failure on a fire truck speeding to a five-alarm emergency. Even as we address the global bonfire driving climate chaos, we will also have to divert our attention to repair the machinery by which we do the public business of voting, legislating, administering, taxing, subsidizing, regulating, and judging. But the machinery of government, rickety though it was, did not break down. It was sabotaged. The neoliberal movement, spawned by Frederick Hayek, Milton Friedman, and others in the late 1940s, proposed to throw sand in the gears and deflate the tires of the New Deal “administrative state” and then denounce government as hopelessly inefficient and markets magically otherwise. They intended to replace government built in large part as a countervailing power to offset that of robber barons, rogue capitalists, and footloose corporations with that of that mythical never-seen creature called a free market. Their success required both Ayn Rand-ian zealotry and amnesia—the great forgetting of the darker aspects of American history that needed sunlight and healing. They succeeded all too well in shrinking our imagination about what good government could be and what it could do while making short-term market share the lodestar of public policy and law. Lewis Powell’s 1971 memo, circulated in the US Chamber of Commerce, called for a corporate counterattack against the New Deal and progressive policies, including civil rights, environmental protection, social equity, public health, education, political accountability, and transparency. Conservative foundations, and others, spent lavishly to create “think tanks” to give a patina of legitimacy to libertarianism and protect use of “dark” money in election campaigns as a form of free speech. They spent even more to create a right-wing media universe centered on FOX “news,” whose business plan aims to keep people tuned in by distraction and anger, appealing to the part of the brain neuroscientists call the amygdala—the ancient reptilian brainstem where ghouls of fear and inchoate violence lurk in the shadows. The predictable results included aflood of unaccountable money, growing inequality, gerrymandered electoral districts, restrictions on voting rights, and an eruption of cynicism, mendacity, and nihilism, all of which exacerbated a widening gap between rural and urban voters that in turn helped to elect a rogue president who, among his other offenses, organized a coup to overturn a legitimate election and undermine the electoral system. If that were not enough, a theocratic majority on the Supreme Court, supported by a militant Christian nationalist movement, intends to impose its pre-Enlightenment predilections on twenty-first-century Americans. The war against American democracy could not have happened at a worse time.

All the while, carbon emissions are rapidly changing Earth into a different and less hospitable planet for humans. Even in the rosiest scenarios imaginable, a warming climate driving more capricious weather will destabilize governments and increase conflicts over water, food, and land, stressing global supply chains and international institutions to the breaking point. It could be worse, but without concerted preventative action, it is not likely to be better. In either case, governing will become more difficult at all levels because of increasing climate-driven weather disasters, the difficulty of making systemic solutions necessary to manage multiple problems without causing new ones, and intensifying conflicts between rich and poor.

One thing more: the US Constitution rigorously protects private property but not what we hold in common and in trust, such as climate stability and biological diversity. It does not acknowledge our dependence on ecological systems with complex feedback loops and cause and effect separated in space and time. It does not protect future generations who will live with the consequences we leave behind—Jefferson’s “remote tyranny,” across generations.

In sum, there is no plausible resolution for the convergence of crises in the “long emergency” that does not include healing our uncivil civic culture and reforming our politics, policies, governing institutions, and laws to accord with Earth systems and a larger sense of solidarity and self-interest that includes our posterity. Our best and, I believe, our only authentic hope is in a renewed commitment to repair and fundamentally improve democratic institutions and governments at all levels. It won’t be easy to do, but much easier than not doing it. Democracy has always demanded a great deal from citizens. Now it requires learning how to be dual citizens in a political system and in an ecological community and knowing why these are inseparable. We must learn—perhaps relearn—the arts of tolerance, neighborliness, ecological competence, and the kind of patriotism that shifts loyalties from “I,” “me,” and “mine” to “we,” “ours,” and “us,” including posterity and other species. I imagine that in some future time we will be judged not just by our technological prowess, but by our skill in the arts of effective, wise, and accountable government—a democracy undergirded by a civically smarter and more supportive citizenry and provisioned by a better-thought-out and more carefully designed technology in an economy harmonized to the carrying capacity of Earth’s various ecosystems and grounded in vibrant and diverse and resilient local communities.

Yale political scientist Hélène Landemore, here and in her book Open Democracy, argues persuasively that we have underestimated our collective intelligence and political competence. She argues that good reasons exist to extend the scope and reach of democracy and find better ways to educate and engage citizens. With Congress deadlocked, the Republican Party mired in quicksand, a politicized Supreme Court, and overburdened government agencies, it is a very good time to enlist the creativity, talents, patriotism, and practical skills of 333 million Americans whose common future is in jeopardy. Writing in 1919, W. E. B. Du Bois put it this way: “The real argument for democracy is . . . that in the people we have the source of that endless life and unbounded wisdom which the rulers of men must have, . . . a mighty reservoir of experience, knowledge, beauty, love, and deed.” The challenge is how to harness the great power and intelligence latent in that untapped reservoir to build a just, inclusive, and sustainable world powered by sunlight.

Visions are easy to dream but hard to implement. If that better, more inclusive, and effective democracy is to grow and flourish, and if we are to be reconciled to the Earth, those more expansive and necessary visions must live in the minds and lives of our youth. For that reason, among others, educational institutions are on the front lines in the battle for democracy and a habitable Earth. Every graduate from every school, college, or university should know how the Earth works as a physical system. They should understand the civic foundations of democracy. They should come into adulthood with a sense of authentic hope in a world still rich in possibilities. For those who teach and administer, it is time to ask, what is education for, especially now? It is time to rethink the enterprise called “research” and better deploy our intelligence and compassion to meet human needs for food, shelter, health care, education, conviviality, safety, and energy.

***

Finally, a word about what this book is and is not: it is a “scouting expedition” intended to describe some of the salient features of the topography ahead. There are four features that we dare not ignore. First, it is imperative to “dis- invent fire” and make a rapid transition to efficiency, renewable energy, and better design of nearly everything. Second, we must reckon with the limits posed by the topography of the centuries ahead. As acknowledged in John Wesley Powell’s 1879 proposal to tailor settlement in the “arid regions” of the US West to the fact of water scarcity, we will confront a series of unmovable limits imposed by climate, ecology, water, thermodynamics, and our own fallibilities. One way or another decisions will be made about the scale of the human enterprise relative to the ecosphere, the just distribution of costs and benefits within and across generations, and what we owe to posterity. Third, the transition ahead is both political, having to do with “who gets what, when, and how,” and moral, having to do with matters of fairness and decency. I see no plausible way to reach that better future without significantly improving our politics, what Vaclav Havel calls “living in truth.” Finally, we must better understand ourselves and what we’ve become shaped by, a culture of consumption that is ravaging the ecosphere, and what we might yet become, with foresight and a bit of help from the angels of our better nature.

This is not, however, primarily a book about policy or recent developments in energy technology or the sins of capitalism, as important as those are. The focus is upstream, on the political and governmental institutions where decisions about policy, technology, and the economy are made, or not. It is, rather, a conjecture from various perspectives about the human response to rapid climate destabilization, and possibilities for improving democratic institutions and civic culture to meet the stresses ahead. Implicit throughout are questions of whether democracy can survive through the turbulent years ahead and become an asset in a transition to a future much better than that in prospect. And our focus is mostly on the United States, in large part because of its greater influence in causing the problem and its greater potential to launch the systemic changes necessary to a decent human future.

The contributors worked at the intersection of a conundrum that sets short-term, fragmented, incremental changes against the need for faster systemic change. We know how to do things in small steps, but the goal should be to take small steps that lead to systemic change with as little disruption as possible. They also worked at the intersection of a five-alarm crisis and an engrained habit of “generally not getting overly excited about anything,” what Naomi Klein calls “the fetish of centrism.” That creates a related communications conundrum. While bombs were falling on London in 1940, for example, Winston Churchill offered the British people only “blood, toil, tears, and sweat,” not a lecture on the joys of urban renewal. On the otherhand, Jack Nicholson’s character Colonel Nathan Jessup in A Few Good Men famously blurted out to a tense courtroom, “You can’t handle the truth.” It all depends. In tough situations, Mark Twain advised that one should tell the truth because it will amaze your friends and confound your enemies. In our circumstances, however, how do we tell the truth without also inducing despair and fatalism? But even in the best scenarios, the temperature of the Earth will rise steadily in the foreseeable future and the resulting weather will be increasingly chaotic, causing immense suffering and losses that did not have to be.

Michael Oppenheimer’s overview of the facts about climate change and long-term implications of a warming Earth sets the stage for the chapters that follow, including his “and yet” expression of faith that we will rise to the challenge. Part I deals with the complexities of democracy and its potential. Frances Moore Lappé argues that unseen possibilities exist “as we bust the myths about democracy being out of reach,” if we can summon the imagination and courage to do “what we thought we could not.” Hélène Landemore focuses on the prospects for “open democracy” that build on our capacities as citizens working in better-designed forums and formats. Daniel Lindvall addresses the capacity of democracies to protect the right of future generations to a habitable Earth. In other words, we have possibilities grounded in our history, and in our capacities for learning, creativity, and empathy.

Part II examines a few of the many roadblocks on the road to democratic renewal and new challenges, of which there are many. Some of these are longstanding structural and procedural problems embedded in the Constitution and our history. Some owe to the very nature of politics in a democracy, which is to say tribalism and human cussedness. William Barber’s opening calls us to seize the moment to transform not only how our society is powered but how we deploy political and economic power to “secure a future for us all, . . . the best that our collective humanity has to offer.” For a society buffeted by uncontrolled technology, David Guston proposes “no innovation without representation,” reminiscent of the commonsense precaution to “look before you leap.” The point is that the market alone is a bad way to deploy complex technologies that affect health, environment, and civility in ways that we often fail to anticipate. Holly Buck’s essay focuses on the “outrage-industrial complex” that has “supercharged” our animosities and warped our “conceptions of democracy.” The solutions require us to understand and restructure “our media environment . . . [to] support our common humanity.” Finally, Fritz Mayer addresses the thorny issues that plague the politics of climate change in an anarchic world of sovereign states where consensus and self-interest collide.

Part III focuses on issues of policy and law. Bill Becker’s analysis of American democracy indicates that we have broken through gridlock before. This time, however, is more demanding: we must surmount “narrow tribalism, manufactured outrage, the absence of a unifying national vision, and the loss of fundamental values.” Lincoln’s “angels of our better nature” wait in the wings. Ann Florini, Gordon LaForge, and Anne-Marie Slaughter propose to better deploy nongovernmental organizations, corporations, finance, and business, building on the imaginative use of self-interest beyond the realm of government to advance the public good. Katrina Kuh and James May analyze the “constitutional silence on the environment” and “judicial abdication” on matters of environment and climate—that is, human survival. Remedy will require an “open-eyed reckoning with how and why the constitutional status quo is failing” and, presumably, jurists and judges who understand the relationships among Earth systems science, jurisprudence, and the human prospect. Batting cleanup in this part, Stan Cox assesses the state of our ignorance relative to what’s knowable and what’s not on a warming planet where the climate is “becoming less predictable year by year.” The prognosis, if not quite desperate, is not quite not desperate, either. “We and future generations,” he writes, “will face the need for profound adaptation” much of which will depend on work at the local level in neighborhoods and communities, which is, I think, good news.

Finally, because our difficulties and perplexities mostly begin with how we think and what we think about, part IV deals with the effort to improve thinking through that complicated process, education. Michael Crow, president of Arizona State University, and his coauthor William Dabars describe the “fifth wave” university response to climate change and the necessary combination of learning, innovation, and forbearance essential for a decent future. The five-alarm nature of climate chaos requires revising curriculum, research, and innovation throughout higher education and changing requirements for graduation so that every student in every field knows what planet they’re on, how it works, and why such things are important for our public life and for their own lives and careers. Wellington (“Duke”) Reiter’s chapter describes the Ten Across initiative, which joins the ten major cities along US Highway 10 from Jacksonville to Los Angeles as a “proving ground for the most critical issues of our time.” It is also an example of the creativity and innovation possible in well-led and imaginative universities. Finally, Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods and the founder of Children and Nature Network, describes the importance of the experience of nature early in childhood and how that opens the democratic vista rooted in a “deep emotional attachment to the nature around us.” The sense of connections early in childhood, by which I mean the awareness that we are kin to all that ever was, is now, and ever will be is the emotional bedrock for a democratic order and those otherwise elusive habits of heart that defy mere reason.

A scouting expedition does not yield a detailed map with GPS precision. But, like the explorations of John Wesley Powell in the Southwest or the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806), we’ve covered what we consider to be the most important features of the complex, chaotic, and surprising world ahead. There is, however, much more to be said. Here we’ve emphasized the need to join a lucid understanding of biophysical reality with how we do the public business fairly, competently, democratically, and with foresight.

More from David Orr: