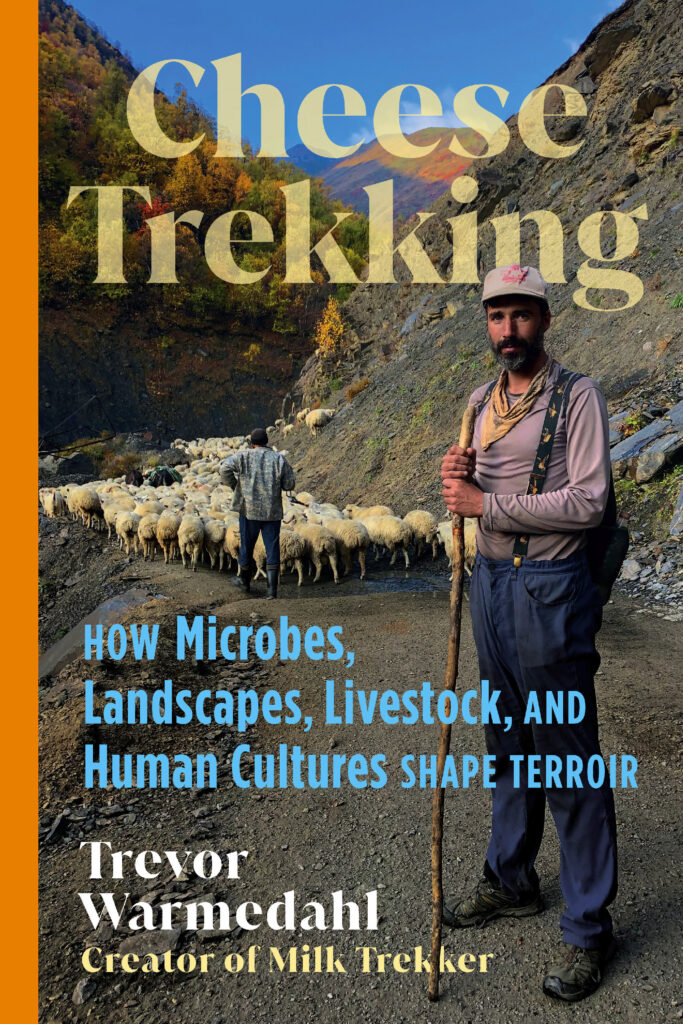

Cheese Trekking: How Microbes, Landscapes, Livestock, and Human Cultures Shape Terroir

Arty Mangan | Published: November 5, 2025 Food and FarmingRestoring Ecosystems Article

Trevor Warmedahl, traveled around the world apprenticing with traditional, pastoral cheese makers. His discovery of terroir–a flavor that expresses the landscape, the animals and the process–came as an almost spiritual revelation while working in the Alta Langhe hills in Italy where they make a regional cheese called Tuma. The following is an excerpt from new book Cheese Trekking: How Microbes, Landscapes, Livestock, and Human Cultures Shape Terroir, (Chelsea Green Publishing February 2026) and is printed with permission from the publisher.

Satori

That the smell of this unassuming little cheese with its microbial wilderness could induce this state of rapture in me as it released its spores and aromatic compounds into the air was revelatory. It was my first cheese satori, to adopt the Zen Buddhist term referring to a sudden enlightenment, a feeling of total presence, an extreme, consciousness–expanding epiphany. That a cheese could have such a characteristic personality made real what had been just a concept before, introduced to me in that Seattle bar ten years earlier. The notion of terroir crept out of my brain like a spreading fungal mycelium and moved through my whole body. Some cheeses are consciousness altering, more entheogen than food. These few moments of heaven are locked permanently in my flavor memory bank, setting a precedent from which I would spend the next three years recovering. Chasing that first high, I would venture into the forgotten folds of the planet where other boundary–dissolving, cheese–born intoxicants lurked, guarded by faithful initiates, persecuted by the servants of an empire that fears everything unabashedly sexual and of the earth.

I had never experienced such an undeniable sensory experience of what I would later dub deep terroir, where a direct aromatic correlation exists between a cheese and the place it is made. That place wasn’t just a creamery, mind you. It was a field of plants about to enter winter dormancy, growing from wet, fecund September earth on a west–facing hillside above a tributary of the Po River in the Alta Langhe hills on the piece of Planet Earth that is temporarily called Italy. The creamery, with its pleasant aroma of souring sheep milk and the yeasty rind of the tuma, could be viewed as a carrier of the terroir seeded by the land and animals. An amplifier, the space in which the seeds of this cheese germinate. That field and this cheese smelled of sheep, with hints of their manure as a seasoning in this aromatic stew. Not in a bad way, but in a pleasant, complementary way. It wasn’t the aroma of many sheep in a closed barn, packing urine and manure into an ammoniated cake without enough interwoven dry plant matter. The aroma of that field included as one element the input of a small flock of healthy sheep with plenty of space, being moved daily. It was a light sprinkle of ovine biology that didn’t overwhelm the other flavors in the stew—the wet grass, dark soil, and rotting leaves. The sheep lay in that field, breathing its air, eating its plants, and walking its contours. The milk carried a certain essence that I couldn’t identify when drinking it. It was likely very subtle, below the threshold of perception for most of us. This essence was then somehow magnified to a perceivable level and altered by the fermentations involved in the cheese make and the subsequent short ripening. Milk can have hints of terroir, but it is really the process of turning it into cheese that can unlock this potential and allow a coherent voice to start speaking.

This cheese is one of the greatest I have tasted, based on that initial powerful sensory imprint left by smelling and then eating it in the place it was produced. Terroir in cheese went from something conceptual to a highly tangible, blissful experience. There was no packaged starter added—the cheese slowly fermented as the bacteria native to the milk sprouted in the infant cheese, into a heavenly cloud of moldy milk that brought me to the verge of a mystical realization. There are cheeses you eat, and there are cheeses that let you shake hands and sit down for a drink with God.