Can a plant “know” its world? Can it adapt, remember, or even make choices? These questions may sound surprising, but they have captured scientists’ imaginations for more than a century. The following article, reposted with permission from The Nature Institute, explores how plants interact with their environments and invites us to reconsider what we mean by “intelligence.”

The Nature Institute, founded in 1998, is a small but influential non-profit in upstate New York. Its work and research is inspired by such integrative thinkers and scientists as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Rudolf Steiner, Owen Barfield, and Kurt Goldstein, who strived to study the natural world with what Goethe described as a form of “delicate empiricism,” an approach that is contextual, qualitative, and holistic. The institute serves as a local, national, and international forum for research, publications, and educational programs that strive to create a new paradigm that embraces nature’s wisdom in shaping a sustainable and healthy future.

Modern science has increasingly moved out of nature and into the laboratory, driven by a desire to find an underlying mechanistic basis of life. In their view, despite all its success, this approach is one-sided and urgently calls for a counterbalancing movement toward nature. Only if we find ways of transforming our propensity to view and control nature in terms of parts and mechanisms, will we be able to see, value, and protect the integrity of nature and the interconnectedness of all things. This demands a contextual way of seeing science as a participatory process, as a dialogue with nature that does justice to the rich complexity of the world.

What follows is the opening piece in The Nature Institute’s research series on “intelligence in nature,” beginning with the remarkable adaptability of plants.

Are Plants Intelligent? An Initial Exploration

By Craig Holdrege and Jon McAlice

Initially, we might view plants as we see many other things in the world: as objects — each complete unto itself and separate from the things around it. When, however, we attend more closely to plants, we find an intricate array of relations in which they play an active role. Roots growing down through the soil not only take up water and minerals, but also secrete substances into the soil and change it. Plant leaves unfold into the air and grow with the help of the light. They form expansive surfaces that create shade for some of their own lower leaves, the ground, and perhaps other plants. Leaves take up carbon dioxide, give off moisture to the atmosphere and, importantly, emit the oxygen that we and animals breathe. Mycorrhizal fungal networks connect physically and physiologically different plant species with each other via their roots.

These examples point to the countless ways in which plants and what we call environment interpenetrate and mutually influence one another. The life of the plant is one of dynamic interactions. There is in this sense no separateness. Can we say where a plant ends and its environment begins?

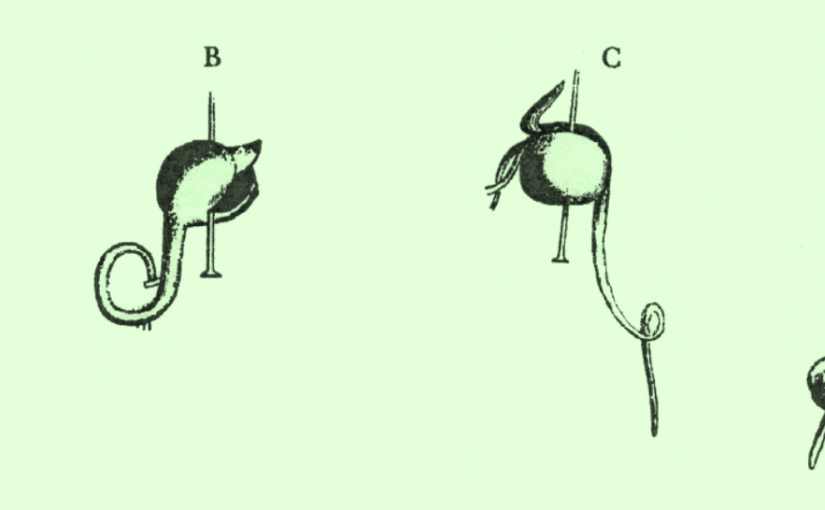

In its life history — from seed through germination, vegetative growth, flowering, fruiting, and new seed formation — a flowering plant is in ongoing transformation. Its development is integrally woven into a specific environmental context that is also changing. This dynamic relation comes to expression in all aspects of a plant’s form and physiology. A wild radish seed that comes to rest in relatively barren, compacted ground or another one at the edge of a meadow only 30 feet away find very different conditions for their development. It could be that neither germinate, but if they do and thrive, they develop in strikingly divergent ways (see image). The plant in the compacted ground grows immediately and continuously in relation to those specific conditions. It develops a few very small leaves, a short main stem, with a couple of flowers, and finally a few fruits and seeds. In contrast, the plant at the edge of the meadow displays effusive growth of branching stems, leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds. If it weren’t for the distinctness of the flower, you might not notice that the two plants belong to the same species.

The compact-ground plant goes through its whole life cycle in a way that intimately corresponds with the relations it takes up in that place. It doesn’t start out with a fixed body plan that prescribes leaves or stems of this or that size or number. No, its becoming is wholly embedded and flexibly active in a specific context. Had the same seed dropped at the edge of the meadow, it would have developed in a radically different way. This is one example of the plasticity that plants reveal in all aspects of their development.The same species of plant has the possibility to be itself differently in different contexts, to subtly respond in its growth and physiology to changing conditions. Clearly, plants have remarkable capacities.

Are Plants Intelligent?

Within mainstream biology, the question of plant intelligence has become a hot — and controversial — topic during the past two decades.1 It is, however, not a new question. In his 1908 address as President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Francis Darwin, Charles Darwin’s son, made the statement: “We must believe that in plants there exists a faint copy of what we call consciousness in ourselves” (Darwin, F. 1908). The notice of his address that appeared on the front page of the New York Times (Sept. 3, 1908) bore the title “Plants as Animals” and stated: “Few more imaginative and more original speeches have been delivered from the Presidential chair than his, though the scientific audience shook their heads.” Francis Darwin’s thoughts sparked a controversy that spanned the Atlantic and led to a flurry of articles. The notion that plants could express anything resembling even the most primal aspects of human consciousness or animal nature was inconceivable for those who worked closely with plants. On September 4, 1908, the day after the initial notice of Darwin’s address, an article appeared on page 6 of the Times with the headline “Scoffs at Theory that Plants Think.” The article quotes at length Dr. W. Alphonso Murrill, assistant director at the New York Botanical Gardens. He says: “When a true plant performs actions that might seem to imply intelligence and a nervous system, I am inclined to suppose that they have developed powers peculiar to plants and quite distinct from the faculties of animals, even though their results appear similar.”

Murrill and his colleagues at the time were convinced that assigning animal or human capacities to plants was “unscientific.” Plant physiology and morphology is fundamentally different from that of animals. In phenomenological terms, we could say that plants are in the world differently than animals. Defining plant existence in terms of animal behavior or human consciousness was, from their scientific perspective, untenable.

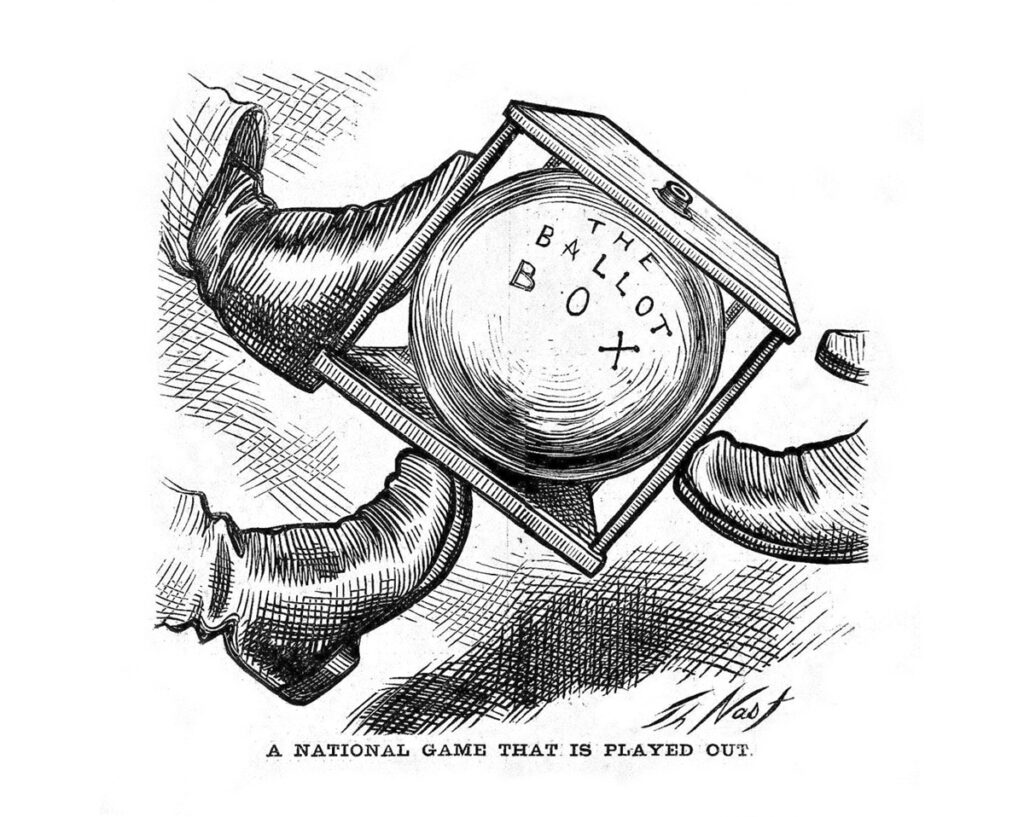

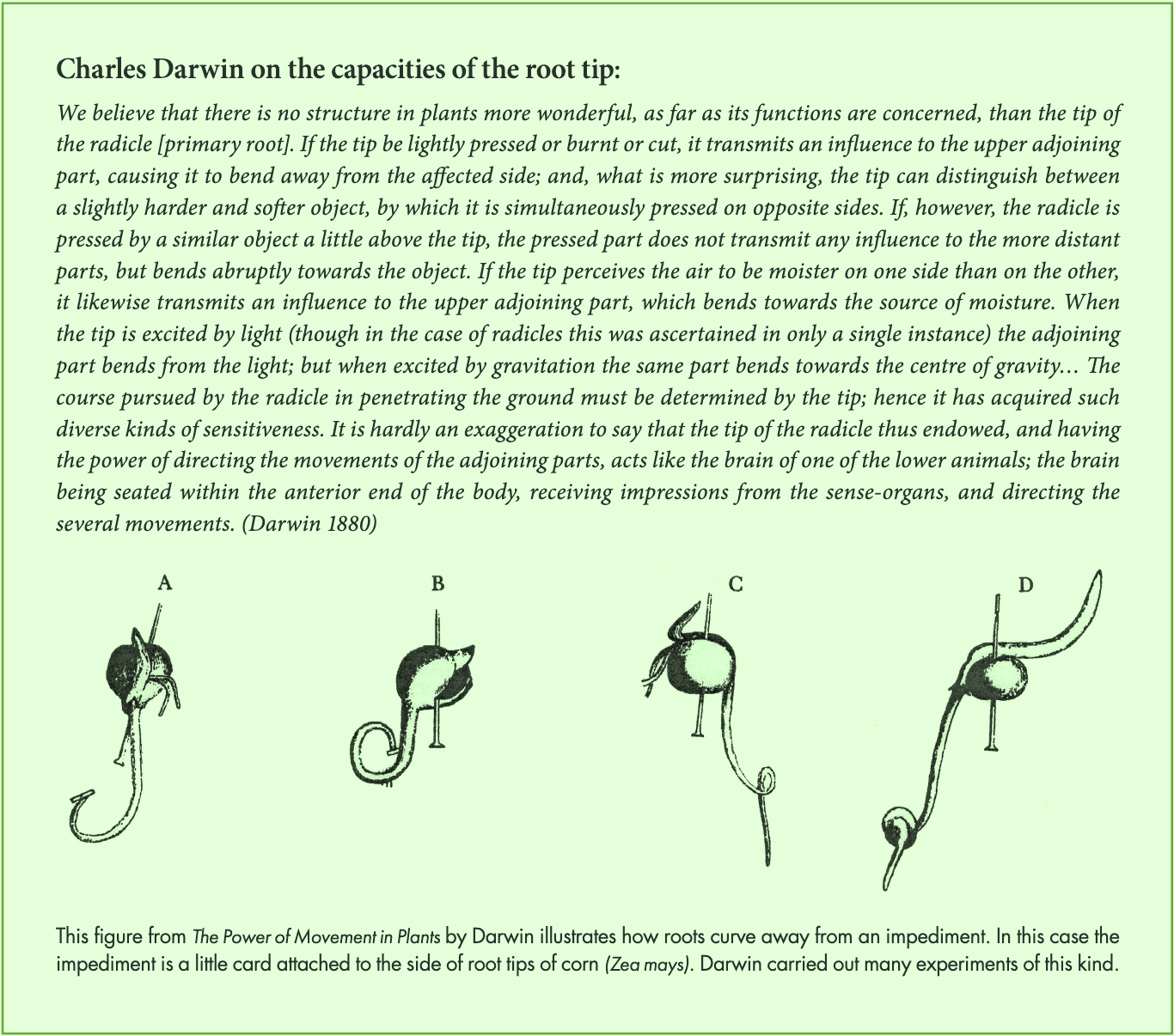

Francis Darwin was drawing from the extensive experimental work he carried out as a young man with his father, which culminated in the 1880 book by Charles Darwin, The Power of Movement in Plants. Without using the term “intelligence,” Darwin ends the book with an enthusiastic and vivid tribute to the remarkable capacities of the tip of the primary root (“radicle”) in plants and ends by analogizing the root tip with the brain of a “lower animal” (see box below with his description).

Through much of the 20th century, the topic of plant intelligence lay dormant. It became, in a sense, forbidden territory as mechanistic explanations for all biological phenomena became ever more dominant. In recent years, a number of researchers have returned to the question “Are plants intelligent?”, answering it in the affirmative. They often cite the authority of Charles Darwin, referring back to his work with plant movement. And like the Darwins, they claim to have identified aspects of plant existence that resemble human intelligence. When you read the books and articles that argue for acknowledging plant intelligence, you see that one major motivator is the desire to raise the status of plants in the eyes of fellow biologists and the general public. They feel that the remarkable capacities of plants have been overlooked or not valued enough. We entirely agree.

Plants, Human Intelligence, and Survival Value

Current plant intelligence researchers lean toward using the way humans experience their own intelligence as the touchstone for their conclusions. This leads them to hypothesize plant modes of perception and representation and conclude that plants “make decisions,” “remember,” “learn,” and “communicate.” They are “able to receive signals from their environment, process the information, and devise solutions adaptive to their own survival” (Mancuso and Viola 2015, p. 5). A recent article provides a good sense of how plant intelligence is viewed:

Plants have developed complex molecular networks that allow them to remember, choose, and make decisions depending on the stress stimulus, although they lack a nervous system. Being sessile, plants can exploit these networks to optimize their resources cost-effectively and maximize their fitness in response to multiple environmental stresses…. In this opinion article, we present concepts and perspectives regarding the capabilities of plants to sense, perceive, remember, re-elaborate, respond, and to some extent transmit to their progeny information to adapt more efficiently to climate change. (Gallusci et al. 2023)

Anthony Trewavas, one of the leading advocates for plant intelligence, writes of seed germination: “The skill in environmental interpretation, that is learning, determines which seeds will most accurately assess the time of germination and environmental conditions for the young plant. These are clearly the most intelligent” (Trewavas 2017).

Trewavas’ approach here is to start from our own self-conscious human intelligence. We can think through what he is proposing in his kind of terms — vividly and literally. Seeds fall onto the earth. Wind and rain, passing animals, or falling leaves cover the seeds and they sink into the soil. They lie there waiting, collecting information and interpreting it in order to determine when they should break dormancy. Each seed is doing this on its own, informed by the strategy that the right decision will bring forth a plant that will survive. Imagine it even more concretely. One calendula plant can produce hundreds of seeds by the end of the growing season. These fall to the soil beneath the plant. They will be rained on, dry out, be subjected to freezing temperatures, be covered with snow, and exposed once more to the sun and the rain. Some will have been eaten by birds or rodents; some may have been penetrated by worms; some rot. In the spring, a small percentage of those that remain will germinate. They have laid there analyzing data and, secretly competing with one another, they wait for the perfect moment to begin to sprout. According to Trewavas, some of the seeds are more intelligent than others. The more intelligent seeds will have interpreted the data more accurately, made better decisions, and are thereby more likely to survive.

For both mainstream science and contemporary plant intelligence researchers, the ultimate ground for intelligence is survival. Here is a formulation in an article in the journal Annals of Botany:

The inbuilt driving forces of individual survival and thence to reproduction are fundamental to life of all kinds. In these unpredictable and varying circumstances the aim of intelligence in all individuals is to modify behaviour to improve the probability of survival. (Calvo et al. 2019)

The emphasis on individual survival in biology goes back to Charles Darwin, whose highly influential theory of evolution has as its central notion the idea that individual variants of a species compete with each other in the context of a hostile environment. This struggle for existence leads to “survival of the fittest” (a phrase coined in 1864 by Herbert Spencer). What’s puzzling about Darwin is that, in one way, he is clearly aware that when he uses phrases such as struggle or competition he is speaking metaphorically or perhaps even improperly:

A plant on the edge of a desert is said to struggle for life against the drought, though more properly it should be said to be dependent upon the moisture. (Darwin 1859/1979, p. 116)

He was conscious of the different connotations of these two ways of phrasing the same phenomenon. When you say “the plant is dependent upon moisture,” you disclose a vital relationship between plants and their environment. Struggling for life, by contrast, implies an agent who stands over and against the world and is confronting something that is for it a problem. Drought is a problem for a plant. Yet although Darwin admits that the notion of struggle in this context is less adequate, less “proper,” his thinking was dominated by the notion of “us against them” — the struggle of entities against each other. This way of conceptualizing and expressing relations was widespread in the social and economic thinking of Darwin’s time. Darwin found in the ideas of competition, struggle, and the survival of the “most favored” the theoretical framework that enabled him to bring his observations of nature into an intelligible whole, even though — as the previous quotation and others in his 1859 tome, The Origin of Species, indicate — part of him evidently felt that there was something not fully appropriate about this way of articulating the relation between organisms and their environment.

Darwin’s words point to the importance of considering how the language you choose affects the way you see and conceptualize the world. In one case, you posit an initial separateness, place the plant in an antagonist relation to, say, the lack of moisture, and imbue the plant with a centered agency through which it struggles against drought. You frame its existence in a way that resembles a human being struggling against something adversarial. In the other case, you view the plant in one of its connections with the world that supports its existence; you don’t start with separation. You express the dependency of the plant on moisture and don’t go further; you leave open what still can be discovered about the nature of this relation.

Language really matters. It is the reflection of our way of understanding the world. It shapes how we understand and even how we experience the world. In science, phenomena are always portrayed through a certain perspective and the language used embodies and enables that perspective. It is important to give due attention to this framing. The phenomena may show quite different features when viewed from another perspective. For that reason, we should appreciate what truths can be revealed by various perspectives. But we also need to be careful to never limit our approach to only one way of looking — which we implicitly or explicitly believe to be the way to consider things — that can hide more than it illuminates.

The language used in contemporary plant intelligence studies generally portrays plants as having human-like intelligence. We know very well from our own experience about remembering, choosing, making decisions, re-elaborating, or responding. Evidently, the proponents of plant intelligence believe there are phenomena within plants that justify such expressions. They look at plants through the lens of what they know about intelligent human behavior from self-conscious reflection and speculate on plant specific mechanisms that underlie the appearance of similar behaviors. Certain features of reflective human intelligence become the standard for how to understand plants.

Expanding the Idea of Intelligence?

Some years ago, there was an article in Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications that listed about 70 different definitions and brief descriptions of intelligence collected from books and articles (Legg and Hunter 2007). Most of the definitions clearly relate to rational human intelligence. For example:

Intelligence is a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience.

Other definitions are more general and broad. A definition such as, “the ability to learn or to profit by experience,” can easily be applied to animals. And plants can surely be said to possess “adaptively variable behaviour within the lifetime of the individual” (in Trewavas 2017).

The broadest criterion for calling something intelligent seems to be: “the ability to adapt to the environment” (Legg & Hunter 2007; reference 13). From this perspective, virtually everything in the world is intelligent: A stone that warms up in the sun is intelligent, because it adapts to the sun’s radiating heat. Similarly, water that flows downhill or remains still in a basin would be intelligent, since its momentary state is adapting to the conditions in which it finds itself. If, following the same definition, we move into the realm of the living, then a plant that grows effusively in a nutrient-rich soil is intelligent. A deer that flees when it sees a coyote on the field is intelligent. And a person who lies down in bed and falls asleep is also intelligently adapting to the environment.

One way to react to such a list of divergent ways of being “intelligent” is to say: When a definition is so broad, it ends up denoting virtually nothing specific. The concept of intelligence then tells us everything generally and nothing in particular.

Another way to respond is to say: That’s interesting, maybe there is some sense in which it might be reasonable to speak of intelligence in plants. But then you have to move beyond thinking in terms of definitions. Definitions generally want to create crisp boundaries so that you have a way to determine what falls within the definition and what is excluded. They are in this sense mental boxes. When you peruse these 70-plus definitions of intelligence, what you discover is a spectrum or a continuum and no hard-and-fast boundaries. In this sense, such a compilation facilitates a movement beyond thinking in boxes.

If we are not focused on including or excluding different kinds of beings based on a definition of intelligence, we can shift our perspective. We consider the idea of the ability to adapt to the environment itself. Everything we designate as a “thing” is also embedded in a world we call “environment.” Every “thing” relates to its world. It might change in relation to changes in the environment, and when it changes, the environment might also change. The concepts of “thing” and “environment” are inextricably connected. They belong together; they presuppose each other. Nothing exists in isolation. Nothing exists without a larger world to which it belongs. So when we delve into any realm of phenomena, we focus on something particular and in our attempt to understand it, we strive to move beyond our ignorance of it by discovering, if we can, the meaning-filled (meaningful) relations of which it is a part.

At the same time, we see that the meaning of “adapt” or “environment” modifies depending on what kind of entity or organism we are considering. Water for a rock is something very different from water for a plant. This may pose a bothersome problem for a mind that wants to start with a clear definition as the basis for including or excluding phenomena within the definitional concept. For us it is exciting to engage in a project in which our concepts may grow with each encounter.

Moreover, while we may discover distinct features of intelligence in, say, plants and animals, we may also find different qualities of what we might call intelligence within a given type of organism.

It is easy to recognize how human beings participate “intelligently” in the world in ways that remain beneath the surface of the reflective, intellectual mind. Imagine dashing madly through an overgrown field. You push through thickets of shrubs, attempt to evade brambles, and focus on finding openings that allow you to navigate the overgrowth in the most expedient manner. You breathe more deeply and your heart rate increases. When you arrive at the other side, you discover scratches on your arms and legs that you barely noticed as you were running. Some are still bleeding, others begin to crust over. Healing processes begin immediately following an injury regardless of whether you are aware of them or not. When the skin is punctured, the surrounding or damaged blood vessels immediately contract, reducing the flow of blood. Platelets converge on the locus of the wound and release fibrin proteins that form a tangled web resulting in a clot sealing the wound. Once the wound is sealed the blood vessels expand, bringing white blood cells to the wound area. As the healing process continues, fibroblast cells produce collagen that scaffolds the placement of new skin cells formed by the division of cells in the surrounding dermal tissue.

All of this takes place inside of us and is done by us beneath the surface of what we consider to be conscious. It happens without our conscious input. We are not deciding or making choices. As with most of what happens in the living world, our self-conscious understanding of these highly meaningful and dynamic processes is extremely limited. Yet they are at the heart of our existence as living beings. And do they not provide the organic basis of our ability to think about the world, to employ our conscious intelligence?

There are apparently different layers or dimensions of “intelligence” within human beings. Realizing this helps free us from the limitation of thinking of intelligence solely in terms of reflective human consciousness. It makes us keenly aware of the pitfall of limiting the inquiry to one particular expression of human intelligence and projecting it into all other forms of life. From this perspective, the question of intelligence in nature shifts away from applying a specific definition to different types of beings in the world to asking: What are different ways of being in the world and what do they reveal? The notion of intelligence can in this way become more nuanced and grow when we take different kinds of creatures on earth seriously in their specific ways of being. Our primary focus in the coming year or so will be on plants. As our inquiry proceeds, we may find that we need terms other than intelligence to express the different qualities of organism-environment relations. We leave that open.

Notes

1. See references for a small selection of publications from the scientific literature, both pro and contra. There are also many popular articles and books that have brought topic into broader societal awareness, among them Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees (2017), and Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree (2021), both international bestsellers.

References

Calvo, Paco (2016). “The Philosophy of Plant Neurobiology: A Manifesto.” Synthese vol. 193, pp. 1323-43. doi 10.1007/s11229-016-1040-1

Calvo, Paco, et al (2020). “Plants are Intelligent, Here’s How.” Annals of Botany vol. 125, pp. 11-28. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcz155

Darwin, Charles (1859/1979). The Origin of Species (first edition). New York: Penguin Books. Online: http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F373&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

Darwin, Charles (1880/1989). The Power of Movement in Plants. “The Works of Charles Darwin”, Volume 27. Edited by Paul. H. Barrett and R. B. Freeman. New York: New York University Press, pp. 572-73. Online: http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F1325&viewtype=text&pageseq=1

Darwin, Francis (1908). “The Address of the President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science-I.” Science vol. 28, pp. 353-62. Online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1636207

Gagliano, Monica, et al. (2014). “Experience Teaches Plants to Learn Faster and Forget Slower in Environments Where It Matters.” Oecologia vol. 175, pp. 63-72.

Gallusci, Philippe, et al. (2023). “Deep Inside the Epigenetic Memories of Stressed Plants.” Trends in Plant Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2022.09.004

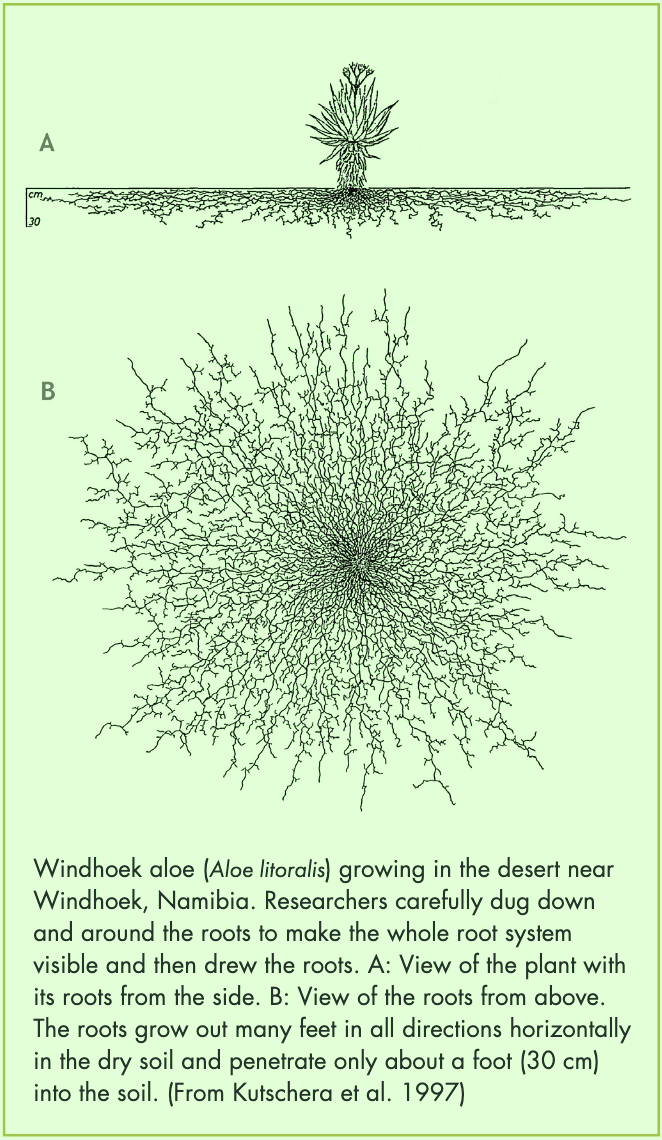

Kutschera, Lore, et al. (1997). Bewurzelung von Pflanzen in verschiedenen Lebensräume. Bd. 5 der Wurzelatlas-Reihe, Stapfia 49.

Legg, Shane and Marcus Hunter (2007). “A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence.” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, vol. 157, p. 17. https://arxiv.org/pdf/0706.3639.pdf

Mallet, Jon, et al. (2021). “Debunking a Myth: Plant Consciousness.” Protoplasma vol. 258, ppl. 459-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-020-01579-w

Mancuso, Stefano, and Alessandra Viola (2015). Brilliant Green — The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Taiz, Lincoln, et al. (2019). “Plants Neither Possess nor Require Consciousness.” Trends in Plant Science vol. 24, pp. 677-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05.008

Trewavas, Anthony (2017). “The Foundations of Plant Intelligence.” Interface Focus vol. 7: 20160098. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0098

More from The Nature Institute:

- In Dialogue with Nature (Podcast) — Conversations that explore our relationship with the living world, often featuring scientists, philosophers, and artists who share ways to see more deeply into nature.

- Doing Goethean Science — An article by Craig Holdrege introducing Goethean scientific practice: a way of observing and engaging with nature that emphasizes connection, perceiving relationships, and deep attention rather than reduction.

- Beyond Intelligence: Life in a Relational World — A piece by Jon McAlice and Craig Holdrege that dives into how we might rethink intelligence — not just as a human attribute but as something relational, emerging in our interactions with the more-than-human world.