Agriculture’s War on Nature: Are Toxic Pesticides Worth the Harm?

Arty Mangan | Published: February 3, 2026 Food and Farming Article

What rational sense does it make to spray food with poison? And yet that is the prevailing method in which food is grown commercially with the exception of a small percent of crops that are grown organically. Chemical pesticides (the suffix “cide” means killer) leave residues on foods that we consume daily. The USDA found that more than 75 percent of fruits and over 50 percent of vegetables contain pesticide residues.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) determines what level of those pesticide residues are “safe.” The standard they use is that the pesticide will not cause “unreasonable adverse effects to humans or the environment.” Determination on whether a pesticide meets that standard is based on research done by the same chemical companies seeking approval for their products. The registration process can take 6 to 9 years, at a cost of millions of dollars. So, companies have substantial incentives to get their products approved and are assisted by a cadre of lobbyists.

According to the Environment Maryland Policy and Research Center, “Big agribusiness corporations have invested millions of dollars in campaign contributions and lobbying to defend agricultural practices that pollute America’s rivers, lakes and ocean waters and to defeat common-sense measures to clean up our waterways.”

Over the years, some government agencies, such as the Public Health Service and Fish and Wildlife have found evidence that pesticides negatively affect human health. After the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book ,Silent Spring, which sounded the alarm on the harms of pesticides, President John F. Kennedy directed the President’s Science Advisory Committee to investigate. The Committee found that pesticides cause environmental contamination and are potentially dangerous to other living organisms, including humans.

Prior to 1962, the government regulated pesticides mainly to verify that chemical preparations were effective, and were less concerned with issues of safety. But with the publishing of Silent Spring, and with support from the Kennedy administration, legislative action to evaluate pesticide safety began. Numerous laws have passed regulating pesticides since then, but do they go far enough to ensure public and environmental health and safety?

Approximately 800 chemicals are approved for agricultural use currently. More than 8 billion pounds of pesticides are used globally every year with the U.S accounting for roughly 11 percent, or more than one billion pounds despite evidence of their association with cancer, and neurological and pulmonary diseases. The soils of 80% of global farms contain pesticide residues. A report from Systemiq titled “Invisible Ingredients: Tackling Toxic Chemicals in the Food System” estimates that the global healthcare cost due to pesticide exposure is $816 billion.

Why, if the EPA’s standard of “unreasonable adverse effects” is being enforced, has

Bayer/Monsanto had to pay out $11 billion dollars in settlements because the courts determined that the herbicide Roundup caused cancer (Bayer still faces another 60 to 70 thousand more Roundup lawsuits)? Why have 25 countries banned or restricted Roundup? And why, if their product is safe, has Syngenta paid $187.5 million in 2021 to settle claims linking its herbicide paraquat to Parkinson’s disease? This is by no means a comprehensive list, just prominent examples that lead one to question the EPA’s rigor in adhering to its own standard.

Even though strong evidence that harm to environmental and human health from pesticides exists, can a case be made that the benefits of pesticide use outweigh the risks? The argument is that pesticides protect crops from damage and disease and without them we would not have a stable food supply. But data from The Rodale Institute contradicts that argument. Rodale has conducted 40-year side-by-side commodity grain trails comparing organic production to conventional (chemical) farming. The research revealed that, “Organic systems produce yields of cash crops equal to conventional systems. However, in extreme weather conditions, such as drought, the organic plots sustained their yields while the conventional plots declined. Overall, organic corn yields have been 31 percent higher than conventional production in drought years.”

How Did Pesticides Become Acceptable?

By some accounts, pesticides have been used for thousands of years. There is evidence that sulphur was used to control pests in ancient Sumeria 4500 years ago, obtained by heating up the mineral pyrite, an iron sulfide, to release the sulphur. Mercury and arsenic salts were introduced later, and the insecticidal properties of chrysanthemum flower extracts (pyrethrum) were discovered around 2000 years ago. As industrialization progressed, much of the source chemicals were waste products from mining and manufacturing such as arsenic, mercury, sulphonic acid and lead in the forms of dusts, granules and sprays. Even some fertilizers were made from industrial waste. By the late 1800s through the early 20th century, kerosene was used for controlling pests like fruit flies, leafhoppers on farms and fleas on pets in homes. Lead arsenate and calcium arsenate were widely used on larger farms by 1900, and were still in wide use till the 1940s and not banned by FDA until 1988. Needless to say, those make up a highly toxic arsenal, even more hazardous than most modern chemicals.

In the latter part of the 19th Century, American farmers experienced an atypically high pressure from pests. This created an opportunity for chemical companies to push their products as scientific breakthroughs that were superior to biological controls and nature-based strategies.

But in the 1890s, a number of poisonings led to opposition to these substances. In 1903, Great Britain set limits for residues in food and drink. American chemical companies fought regulation and for 60 years, US regulators failed to support limits even though dozens of reports of serious food poisonings were reported in both US and Europe.

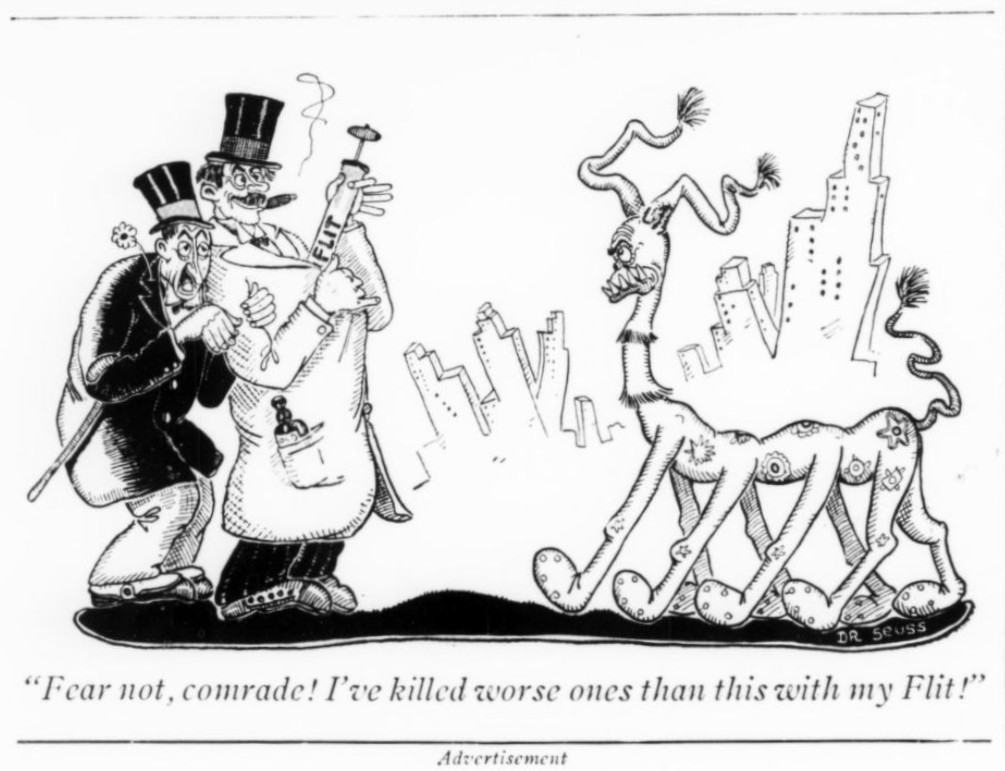

Organic farming pioneer, Will Allen, in his comprehensive book War on Bugs, tells the story of the evolution of pesticides and how the public came to accept them with the help of an unlikely player, popular children’s book author, Dr. Seuss.

In the early 1900s, nearly 40 percent of Americans were farmers (today that number is less than 2%). Farm journals, at that time, were influential sources of information read by a large portion of the population and even used in some schools as reading material. The majority of advertisers in those journals were chemical companies. So the journals were eager to tout the benefits of the products that provided their main income stream while minimizing their toxic impacts.

By the 1920s, chemical companies, seeking ways to expand their markets into households, promoted the concept of “chemical cleanliness” to rid the home of insects and rodents. In 1928, cartoonist Theodore Geisel, was hired by Standard Oil to promote its pesticide Flit. Geisel later gained fame under the pen name Dr. Seuss, as the author of the loveable and whimsical children’s books such as The Cat in The Hat, Green Eggs and Ham and many others. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Geisel’s humorous advertisements made Flit a household name. Geisel’s cartoons, which appeared in thousands of magazines and newspapers, were, in fact, advertisements promoting the pesticide. One such cartoon showed a family scene with the caption: “Don’t worry Papa, Willie swallowed a bug, so I’m having him gargle with Flit.” Standard Oil’s advertising campaign was successful in convincing the American public to embrace pesticides as safe and a normal part of homelife. In War on Bugs, Allen pulled no punches assigning culpability to Geisel, “Seuss helped Americans become friendly with poisons.”

Beating Swords into Plowshares: Wartime Chemicals Repurposed for Agriculture

With America’s entry into World War II, there was a sudden demand to supply the military with a wide variety of critical needs. Chemical companies and other industries retooled factories producing peacetime products to supply the materials needed for war. Everything from synthetic rubber and plastics to explosives and pesticides. American soldiers were equipped with an individual supply of DDT for delousing, and killing bed bugs and malaria carrying insects. DDT was acclaimed for its role in controlling a typhus outbreak during World War II in Naples, Italy when American forces deloused a million Italians with DDT powder.

Post war, companies such as Dow, DuPont, Standard Oil, Monsanto and others transitioned their factories back to products for families, farms, and industry. Ammonium nitrate, used extensively during the war to make bombs, was converted into nitrogen fertilizer. Nerve gas developed by the Nazis became the basis for many pesticides.

As the chemical industry moved into the post war boom era, they were riding high in both profits and public approval, widely admired for the scientific breakthrough that led to an era of “better living through chemistry” thanks to the “miracles of science” (a couple of advertising slogans promoted by Dupont).

Challenged by an Unlikely Antagonist

But the industry’s prosperity and favorable reputation would face a serious challenge from an introverted marine biologist and best-selling author known for her lyrical nature writing.

In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson revealed the shadow side of the so-called “miracles of science” by describing how the widespread, indiscriminate use of pesticides entered the food chain. With a particular focus on DDT, she explained how it was poisoning ecosystems and killing fish, birds and insects as it persisted in the environment long term and accumulated in the fatty tissues of animals, including human beings, and caused cancer and genetic damage.

Carson, deeply distraught by how man’s war against nature was upsetting the ecological balance with grave, long-term effects, wrote, “Intoxicated by his own power, mankind seems to be farther and farther into experiments for the destruction of nature and of the world.”

An organized campaign by the chemical industry called Carson a hysterical woman (the use of “woman,” as well as “hysterical,” was also meant to be a discrediting pejorative by the chauvinistic, male-dominated science world).

Silent Spring, which has sold over 2 million copies and has been translated into 16 languages, awakened public environmental consciousness and led to a domestic ban of DDT. Carson’s book is not only credited with starting a movement to regulate pesticides, it is widely acknowledged, along with the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill that killed thousands of wildlife and polluted 35 miles of coastline, as the beginning of the modern environmental movement. In 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency was formed. The NGO, National Resources Defense Council, also founded the same year, has been heavily involved in legal battles to restrict harmful pesticide use.

The Green Revolution: Some Promise, but Ultimately a Flawed System

Despite the momentum to create a sane and safe approach to agrochemical use, a countervailing movement had been gaining favor around the same time. The high-yielding hybrid seeds of the Green Revolution came with the promise of “feeding the world.” Credited with saving one billion lives from starvation, Norman Borlaug, acknowledged as the “Father of the Green Revolution,” was given the Nobel Peace Prize. But the overlooked caveat of Green Revolution technology was the fact that the hybrid seeds are highly dependent on synthetic, petroleum-based fertilizers to obtain those high yields, as well as pesticides due to their inferior resistance to pests and diseases compared to more traditional crops.

Hybrid seeds were the central element to the new intensified farming system that also included monocropping and mechanization. But over time, the flaws of that system began to reveal themselves. Monocropping encouraged greater pest infestations requiring more applications of pesticides. Chemical fertilizers and plowing destroyed the health of the soil, which resulted in weakening the immune response of plants. And due to heavy, repeated applications of pesticides, insects over time became resistant.

Pesticide Action Network (PAN) describes the declining benefits of the Green Revolution in this way, “In 1982 the luster of the Green Revolution was beginning to fade. The promised dramatic increases in yields from ‘miracle’ hybrid grains that required high inputs of water, chemical fertilizers and pesticides failed to deliver and were revealed as campaigns to sell technology to growers who couldn’t afford it.”

Despite the growing evidence of the flaws of the system, it has endured as the dominant agricultural paradigm often driven by inflated claims. The next evolution came in the 1990s with Genetically Modified (GMO) crops. After decades of industry promises of unrealized future innovation and aggressively promoting their technology by monopolizing the seed markets for corn, soy, canola, cotton and sugar beets, their main success is producing herbicide resistant corn, soy, and canola. The technology allows the farmer to spray over the crop killing the surrounding weeds but not the crop itself. Monsanto/Bayer leads the way with Roundup Ready seeds. Tests have shown that these crops often contain higher residues of glyphosate than non GMO seeds of the same crops. The price of this “success” is the billions of dollars of legal settlements that Bayer is paying to victims who have contracted cancer due to exposure to glyphosate.

In the 1990s and beyond, chemical companies such as Monsanto, Syngenta, Dow, DuPont, and Bayer bought up seed companies. By the 2000s, five of the world’s seven largest seed producers were chemical companies who viewed seeds, not as the foundation of a healthy food system, but rather as a mechanism to sell more chemicals.

As a result, we live in a chemically saturated world. The EPA has approved over 80,000 chemicals with hundreds of new ones added each year. In a small test, the Environmental Working Group tested umbilical cords gathered by the Red Cross and found on average 200 chemicals including pesticides. When it comes to chemical pollution, agriculture is not the only source, but it is the most dominant, fouling the air, polluting waterways, soils, people and wildlife.

Grass Roots Action Fills in Where the FDA Falls Short

With ubiquitous chemical contamination and increasing evidence of its harms–cancer, neurological, reproductive and endocrine systems disorders–why does it appear that the EPA seems too often to favor industry interests over public safety?

The undisputable fact is that there is a “revolving door” between industry and FDA through which former chemical industry personnel go to work for FDA and former FDA employees go to work in the chemical industry. The opportunity for conflict of interest is a genuine concern.

In the absence of rigorous regulatory agency oversight to sufficiently safeguard public health, where do we look for answers?

The first line of refuge for personal health is organic food and Certified Organic Regenerative (ROC) foods. Regenerative agriculture is the evolution of organic farming which emphasizes soil health, healthy ecosystems and highly nutritious food. However the term “regenerative” is used in different contexts and if it is not labeled ROC, you cannot be sure that it has not been sprayed with herbicides or pesticides. Unfortunately, organic food does generally cost more and that can be a barrier for some.

The Environmental Working Group has a downloadable PDF titled “Clean Fifteen and Dirty Dozen.” If you can’t buy organic food, this guidelines lists the 15 foods that carry the lowest pesticide residues and the 12 foods to avoid that have the highest amount of pesticides.

Other organizations are working to transform the food system to one that is free of toxic pesticides.

The Center for Food Safety takes legal action against the FDA and the big agriculture companies such as Monsanto, and is an excellent source for pesticide information.

Beyond Pesticides works with local groups to promote organic land management practices that embrace a precautionary approach by eliminating toxic pesticides.

Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the first national environmental advocacy group to focus on legal action, has taken the first Trump administration to court 163 times and been victorious in 90% of the cases.

No one is more vulnerable to pesticide exposure than farmworkers and their families. The UCLA Fielding School of Public Health has identified 13 pesticides correlated to the onset of childhood cancer between birth and 5 years old, when the mother lives within 2.5 miles of pesticide application while pregnant. Farmworker families suffer disproportionately high rates of debilitating, pesticide-related diseases that are devastating families. A small, grassroots organization, Campaign For Organic and Regenerative Agriculture (CORA), is challenging the largest berry grower in the world to initially transition all of their berry fields near schools to organic and ultimately to convert their entire production to organic farming to eliminate these avoidable and tragic health risks.

The name Silent Spring is a metaphor for a time when the environment becomes so toxic and deadly that many species are wiped out and the sound of the songbird ceases. Rachel Carson found the war against nature to be incomprehensible and questioned its irrationality, “How could intelligent beings seek to control a few unwanted species by a method that contaminated the entire environment and brought the threat of disease and death even to their own kind?”

For more articles like this sign up for the Food Web newsletter