Water makes life possible. From the tiniest bacteria to the tallest tree, every living thing relies on this irreplaceable substance. Erica Gies, author of “Water Always Wins,” explores water’s unique role in the web of life, and how we might repair and reshape our relationship with it. Rather than telling water what to do, maybe we should start by asking what it wants?

This is an episode of Nature’s Genius, a Bioneers podcast series exploring how the sentient symphony of life holds the solutions we need to balance human civilization with living systems. Visit the series page to learn more.

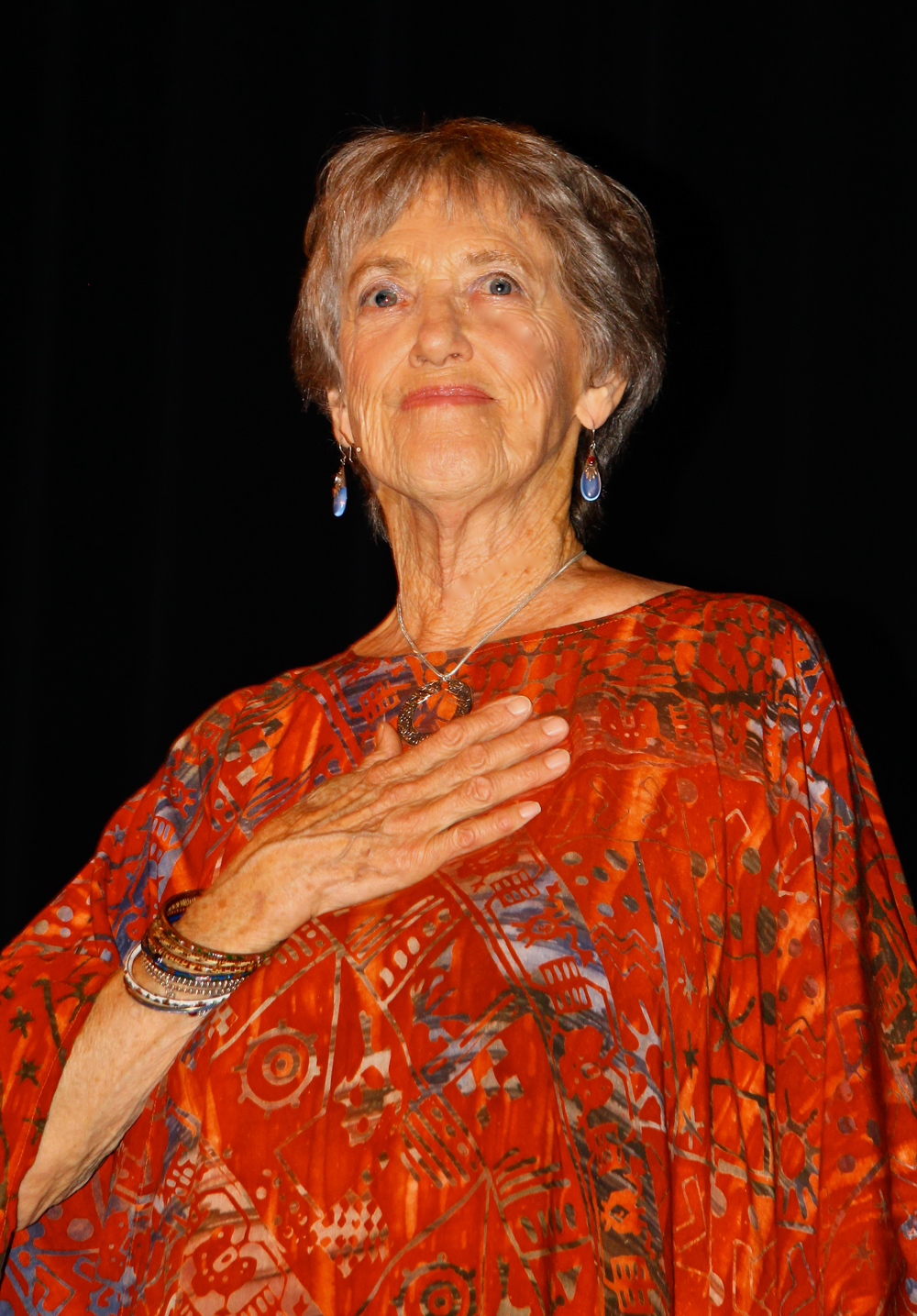

Featuring

Erica Gies is an independent journalist, National Geographic Explorer, and the author of “Water Always Wins: Thriving in an age of drought and deluge.” She covers water, climate change, plants and wildlife for Scientific American, The New York Times, bioGraphic, Nature, and other publications.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Cathy Edwards and Kenny Ausubel

- Produced by: Cathy Edwards

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Production Assistance: Kaleb Wentzel Fisher and Monica Lopez

Resources

Erica Gies – The Slow Water Movement: How to Thrive in an Age of Drought and Deluge | Bioneers 2024 Keynote

Embracing Slow Water: Rediscovering the True Nature of Earth’s Lifeline | Excerpt from “Water Always Wins”

Deep Dive: Intelligence in Nature

Earthlings: Intelligence in Nature | Bioneers Newsletter

This limited series was produced as part of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature radio and podcast series. Visit the homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

Neil Harvey (Host): Water literally makes life possible. From the tiniest bacteria to the tallest trees, all living things rely on this irreplaceable wonder.

We hear from Erica Gies, author of “Water Always Wins”. She turned to people she calls “water detectives” to learn how we might repair and reshape our relationship with this blue gold that sustains life.

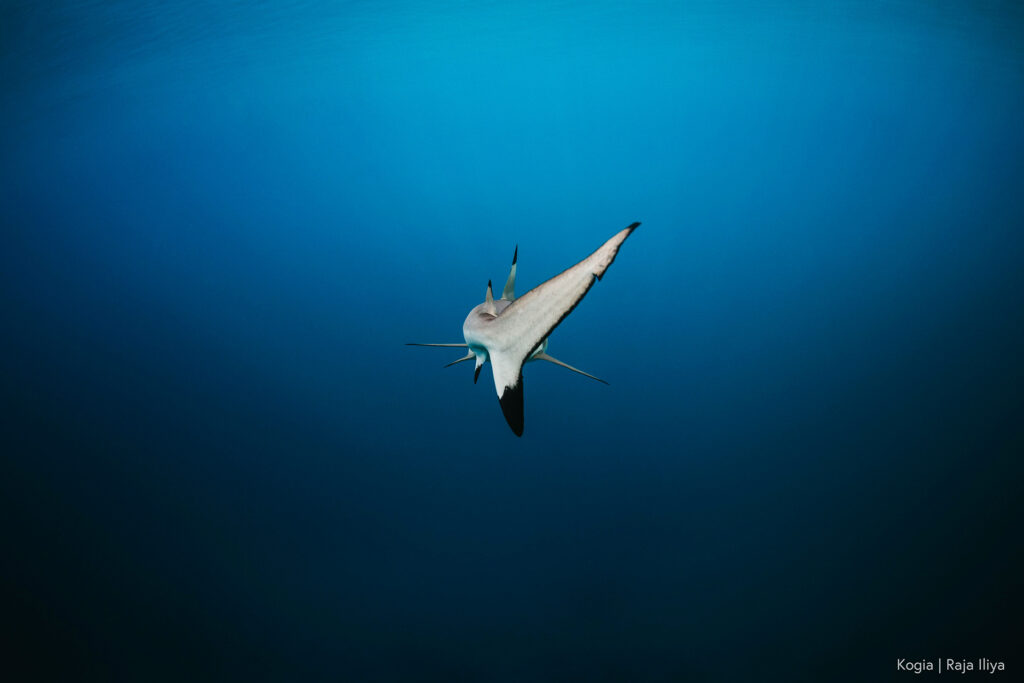

We live on a blue planet. Water is foundational to the chemistry of life on Earth. Leonardo da Vinci called it the ‘driving force of all nature’. Water transports nutrients, fills cells, and helps regulate the temperatures conducive to life. It also physically shapes the planet, too – carving out valleys, canyons and coastlines in slow geologic time – or sometimes in fast forward.

Water is ever-changing, traversing the globe as ice, vapor or liquid – yet every single drop stretches back into deep time. And all the water that’s here has been here for most of Earth’s history. Perhaps the water you drank today was once snow that fell on a wooly mammoth. Or shot out of a hydrothermal ocean vent, where life may have begun billions of years ago.

More recently, humans have sought to control water on vast scales: diverting mighty rivers, or building massive dams and reservoirs. But such brutalist interventions disrupt and damage the intricate relationships water has forged over geological timescales – creating unintended harms that plague civilization today.

So, rather than forcing water to do what we want, what if we start asking what it wants?

Erica Gies’ award-winning book ‘Water Always Wins’ maps the connections forged by water as it cycles through ecosystems.

One of the most startling examples is the interplay of water with forests. The symbiotic dance among forests, air and water illuminates a true marvel of planetary-scale ecology, which she described at a Bioneers conference.

Erica Gies (EG): Scientists used to think that most rain came from evaporation over the ocean, but now they know that at least 40% on average over continents, as high as 70%, comes from evapotranspiration from plants and soil. [APPLAUSE] And that vapor condenses into rain and falls again locally and regionally, something called precipitation recycling. And forests, with their rough surface, also help to create the rain because they are slowing the wind, and they’re releasing particles—fungal spores, pollen, and bacteria—which also help that vapor condense into rain. [APPLAUSE]

And these forests exhalations feed into jet streams and atmospheric circulation. So they’re seeding rain on the other side of the world. And on the flip side, forest loss can cause drought on the other side of the world.

People used to think that the temperature difference between the ocean and the land is what pulled in the vapor, and that trees grew where rain fell. But atmospheric physicist Anastassia Makarieva has shown that forests actively pull in the wind to deliver the rain that they need. Tree vapor condensing into clouds decreases local air pressure, which draws in more moist air from elsewhere. And she calls this the biotic pump. And that might sound radical to some ears, but it’s really not, she told me. All organisms possess knowledge of physical laws that allow them to make use of the environment.

Host: This biotic pump hypothesis challenges the conventional scientific paradigm. It asserts that forests don’t just grow where water happens to fall. Instead, they actually pull in winds to deliver rainfall. It depicts a whole-systems view of the climate, mediated by water’s dynamic relationships with all living things.

But humans have radically altered these elaborate planetary water cycles. The extreme floods and droughts we’re experiencing are often unnatural disasters related to climate disruption – and by failed attempts to control water in misguided ways.

EG: Humans have drained or filled as much as 87% of the world’s wetlands, dammed and diverted two-thirds of the world’s large rivers. The land area covered by pavement in our cities has doubled, just since 1992.

In the dominant culture, we concern ourselves with human needs, and that leads to a single focus problem solving. Worried about scarcity? Build a dam, bring in water from somewhere else. Worried about flooding? Build a levee, build a wall.

But putting ourselves first in this way isn’t working, and it’s because that single focus ignores water’s agency and water’s complex relationships with soil, and rock, and microbes, and plants, and beavers and people. And by ignoring those complex systems, it damages them.

It’s an environmental justice issue. Levees, for example, may protect one community, but in so doing, by cutting off the river from its flood plain, they’re raising the water level in the river, which increases flood risk for other communities who perhaps can’t afford a levee. Dams similarly are an environmental justice issue. A 40-year survey of dams built around the world found that they brought water to 20% of the world’s population but decreased water availability to 24% of the world’s population.

But this problem is also an opportunity, an opportunity to change our relationship with water. Instead of seeing water as a what, a commodity or a threat, many Indigenous and land-based peoples around the world instead view water as a who, a friend or a relative. [APPLAUSE] That lens allows them to better see and understand water’s relationships, including the relationship with people, and to understand that with rights comes responsibility for maintaining and caretaking these systems.

Host: Structures such as concrete dams, levees and seawalls subvert water from where it wants to go. Because water is such a powerful force, it presents a constant struggle against the laws of physics. Levees regularly fail, causing flash flooding. Seawalls may protect particular zones, but they worsen erosion elsewhere.

In the end, water will have its way. It has formed its relationships over billions of years of evolution. The dynamic complexity is likely beyond our comprehension. So it’s not surprising that Erica met many people working with water whose first principle is humility.

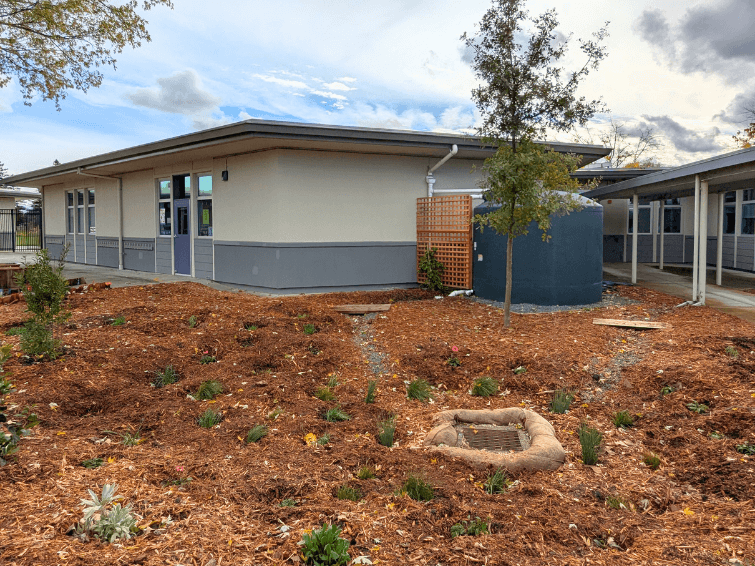

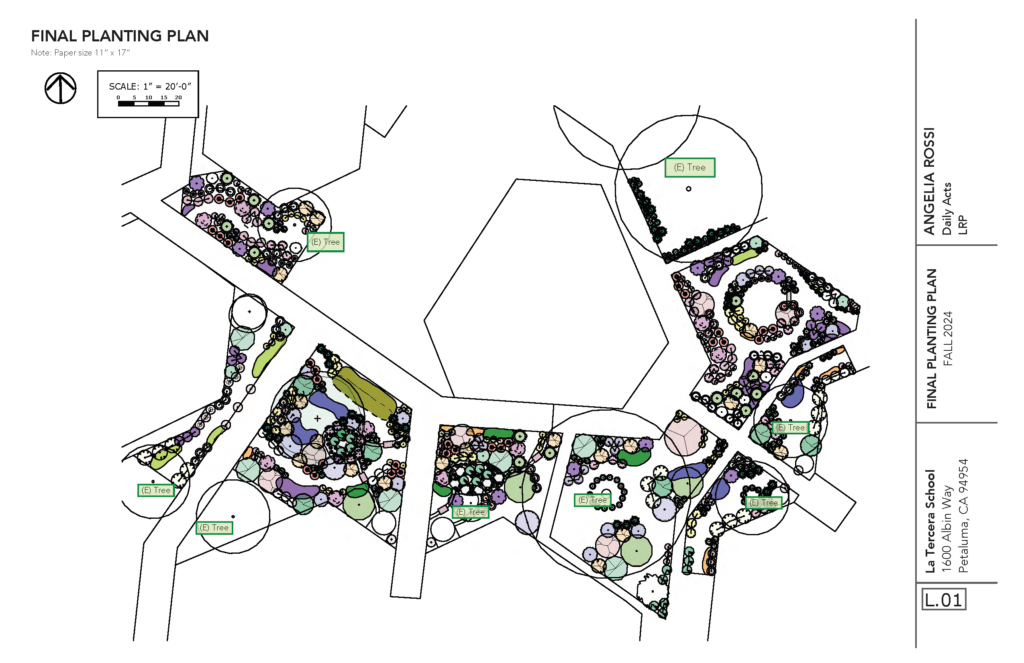

EG: Instead of trying to solve one problem at a time, the water detectives—as I came to think of them, because they approach water with respect and curiosity, and these are engineers, ecologists, landscape architects, Indigenous Peoples, urban planners, farmers, ranchers, foresters—are instead asking a radical question: What does water want? [APPLAUSE] And what I’ve come to understand…is that what water really wants is a return of its slow phases that are particularly prone to our disruption. These are wetlands, flood plains, mountain meadows and forests that absorb floods, clean water, store it for later, store carbon, and support life that maintains the health of these systems that in turn support us.

Host: Figuring out what water wants requires some serious sleuthing. That’s especially the case in cities, where centuries of construction have dramatically altered the natural landscape. So these water detectives engage in what’s called historical ecology. They look for evidence of where water used to go.

EG: Water is inclined to go where it wants to go, which is where it went before we subverted it. And so by mapping what used to be, we understand that homes built on wetlands are often the first to flood. And doing this kind of mapping allows cities to plan for when buildings turn over. Perhaps instead of building something else that’s at risk of flooding, perhaps, you know, we can return that space to water and have a more resilient city. [APPLAUSE]

Host: Erica visited a project in Seattle that began with the goal of stopping local flooding. By uncovering the deep history of water there, they found they could benefit the area in myriad other ways, too.

EG: In Seattle, they used historical ecology to plan for the restoration of Thornton Creek, which was regularly flooding a road, a high school, and homes. And globally, the majority of urban streams are buried and built on top of them, and ones that remain on the surface first they’re deforested, then they’re straightened. That causes a kind of firehose effect, the ultimate in fast water, which scours, and so then it’s armored to prevent erosion. And this creates something that ecologists call “urban stream syndrome”, which is flash floods, unstable banks, heavy pollution, and waning life.

So restoration of urban streams has typically involved removing the cement, putting back some curves, putting in some wood and boulders. You know, making it look kind of habitaty. [LAUGHTER]

But what ecologists found is that the life that was coming back wasn’t very diverse. It was sort of a crows and cockroaches situation. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] And these restorations needed ongoing maintenance.

So a biologist who worked for the city named Katherine Lynch realized it’s not just the stream we see, but the stream that we don’t see flowing underneath that channel. It’s called the “hyporheic zone”, which is from Greek—hypo-rheic, which is “under flow”. So there’s another river that is moving downstream through the soil and rock, but orders of magnitude more slowly.

On a creek, it could extend 30 feet from the banks. On a large river it can extend a mile on either side. And the hyporheic zone is home to all kinds of amazing critters— microbes, crustaceans, worms, aquatic insects, salmon lay their eggs there. And these critters play a pivotal role in nitrogen, phosphorous and carbon cycling. It’s basically like the stream’s gut microbiome. And so that’s why, when the hyporheic zone is scoured away, the waterway has very little hope of staying healthy.

Host: Because natural landscapes such as meadows and fields are porous, rainwater soaks in and disperses much more slowly, providing a steadier flow and temperature throughout the year, all of which fosters richer biodiversity. Slow water creates conditions conducive to more life.

Recreating these intricate water landscapes in built-up urban environments is especially challenging.

EG: This project that Katherine Lynch conceived of to rebuild this missing hyporheic zone, an urban stream, was the first in the world. [APPLAUSE] Yeah.

They put back in some of the curves. They took out the cement. They carefully designed the rock and wood so that it would drive water down into the hyporheic zone. And because they did their historical ecology, the project was just 1600 feet in a river that was 15 miles long, and yet, the reason this area was flooding is because it was a flood plain. So by returning the flood plain to the river, it had an outsize impact and has eliminated flooding in this area. [APPLAUSE]

They did a chemical study. They measured more than 1900 pollutants, things like lawn fertilizer and brake pad dust that are just rushing off the urban concrete and diving into this stream, and they found that spending just three hours in a 15-foot section of the hyporheic zone reduced 78% of the chemicals by at least half. [APPLAUSE]

A few other markers of success, it’s a wonderful place for the community, the city hasn’t flooded, and chinook salmon returned and spawned in this hyporheic zone they created. [APPLAUSE]

Host: The outsized success of this kind of project is inspiring water detectives to radically reimagine our approaches to water engineering.

After the break, we’ll learn more about the growing global movement to foster a more harmonious relationship with water that can help nature heal, and ourselves with it.

Host: A watershed is an area of land that channels rainfall and snowmelt to rivers and eventually to the sea. Human interventions in the water cycle can in fact be very beneficial, if we consider the question ‘what does water want?’

According to water ecologist Brock Dolman, the goal of managing a watershed sustainably is to “slow it, spread it, sink it.” Erica Gies discovered that humans helping to return water’s slow phases has become a growing “slow water” movement.

EG: The slow water movement is a global movement that goes by different names around the world, but they’re all looking to return space to slow water, so restoring or protecting wetlands, flood plains, mountain meadows and forests. These projects are local; they are unique to each place. Every place has unique geology, ecology, and culture, and these projects work within that.

Slow water projects use systems thinking rather than that single-focus problem solving. They are environmentally just. They don’t take from some and give to others, or protect some at the expense of others. And they really do respect nature’s agency, and try to work with water and nature rather than try to control it.

And in all these ways, water slows in its path, and often has time to move underground, sometimes going down with tree roots, sometimes filtering through the hyporheic zone into the aquifer. But that water/land relationship and interaction is really, really important for the hydrological cycle in all kinds of ways.

Host: In contrast to huge, centralized water infrastructures that dramatically halt or speed water up in its path, slow water projects are, by design, smaller and spread out across landscapes.

EG: One thing about the slow water projects is, you know, in our dominant culture, we’ve gotten used to centralized water projects that are managed by experts. So that might be a giant dam and reservoir, for example. But slow water projects tend to be smaller and many of them distributed across the landscape. So instead of centralized, they’re distributed. And that makes sense if you think of that 87% of the world’s wetlands that we’ve eradicated, because you need lots of spaces throughout the watershed, following water’s entire path, for it to slow again.

And a lot of the places I went in the world, in places like Peru or India, I met people who were actually actively building these projects and working with their neighbors on the land to restore these systems.

Slow water projects are something that people can do in their own communities with their neighbors to make themselves much more resilient, and the impact is cumulative.

Host: While the slow water movement has been picking up speed in recent years, some of its methods draw on ancient water management techniques.

EG: So most of the projects I looked at were trying to conserve or restore, or mimic a slow water phase, so returning part of a flood plain to the river, restoring a wetland or protecting a wetland from development, or assisting beavers as their populations recover and they return to the landscape.

There’s a couple of chapters in my book where I look at older human techniques for managing water, and pretty much anywhere people had intermittent rain, you know, a longer dry season, and they were farming, they figured out a way to make the most of the water that came. And that often involved moving it underground in some way, because that dramatically extends the time in which the local rain that you get can be available to you locally.

I looked at a culture in Peru from 1400 years ago called the Huari. The Tamil people in South India for 2,000 years had a system called the eris system. These were not irrigation projects. These were people inserting themselves into the local hydrological cycle and sort of expanding what nature was already doing.

Host: Slow water projects in Peru today are reviving these ancient techniques in direct response to the climate crisis.

EG: In Peru, it’s a very water scarce place. They, like California, have a long dry season, and about 65% of the population lives on the very arid coastal plain, and they rely on mountain water from the Andes, which are right at their back. Historically, they’ve had glaciers, and so those glaciers have melted slowly throughout the dry season and they’ve had water year round. With climate change, some of those glaciers are already gone; other ones are melting rapidly, and the population is growing.

So one project involves restoring this 1400-year-old technique for extending water availability into the dry season. So there are at least three high Andes towns where communal farmers still use this system, which is called “amunas”, which is a Quechua word that means “to retain”. And when the river runs high in the wet season up at very high altitudes, they divert it into these natural infiltration basins, and then the water filters underground, and then it continues moving down the mountain, but much more slowly, because it’s moving through all that soil and rock. And then there are springs lower down the mountain where it emerges, and then they harvest it, and they have complex systems for sharing it and for maintaining this system.

A lot of it had fallen into disrepair, so in some cases they’re restoring it. Because ultimately, when the farmers take that water and water their crops, a lot of that is going to go underground again and ultimately make its way down into the valley bottoms into the three rivers that supply the capital city of Lima.

And similarly, there are these special high altitude wetlands called bofedales, which—or cushion bog—and those are a very important place for slowing water, particularly as the glaciers melt. And they have been victim of peat thievery for the nursery trade. And, you know, when you cut out a square of peat and you separate the bog from its neighbors, the whole thing dries out and dies. So some of the money is going to protect the remaining ones, and some to restore the ones that have been damaged, and there is actually an ancient technique for expanding the footprint of the bofedales. And so some research has been studying how that’s done and how effective it can be.

Host: Restoring the infiltration basins and bofedales of the Andes directly helps human communities survive by evening out the water supply across the country and throughout the year.

However, what water wants is to nourish the entire web of life, not just to fulfill human priorities. There’s good reason that cultures and religious and spiritual traditions from time immemorial have held water as sacred.

If we relate to water not as a commodity but as our beloved relative, the questions arise: Does the web of life have an intrinsic right to exist? Has the absence of such an ethic precipitated today’s ecological crisis?

EG: The bofedales are an incredibly important resource for all of the critters and birds who live in the high Andes. But, in all of the projects I looked at, even if we’re looking at it from a selfish point of view, it’s these microbes, these plants, these animals that are also maintaining the water system. You know? They all work together to keep it healthy and functioning.

And so I believe that other beings have the right to exist separate from whether they benefit humans. However, when they are allowed to do what they do, they also benefit humans. And I think that’s something we’ve lost sight of, you know. The reason we’ve been able to do a lot of what we’ve done in terms of kind of controlling nature is because there’s still been a lot of buffer that has supplied these critical things that we need.

But now, like 75% of land on Earth has been degraded by our activities, so we’re running out of that buffer, and that’s another reason why we’re seeing this big uptick in floods, droughts, mega fires, etc., because we just don’t have that buffer anymore. So it’s so, so incredibly important for our own survival and health and quality of life, as well as the animals and plants who live in these systems.

Host: One thing’s for sure: when you fight nature, you lose. If water always wins, perhaps we can embrace our place as partners in the web of life by asking a most basic question: How would nature do it?

EG: I’ve come to understand that water absolutely has agency. It does. I think humanity, especially recent humans, in the dominant culture, have a history of undermining or ignoring animal intelligence, plant intelligence for sure, and I think a lot of it was really convenient. If you don’t think of other beings as being intelligent or as having agency or as being worthwhile or worthy, you create a permission structure where it’s okay to exploit them and not care about them and not think about them.

I write about science and I love science and I love scientists, but Western science is very reductionist, and that helps you get at certain specific answers, but often you miss the forest for the trees, literally, because you’re siloing what you are trying to figure out. So I think that natural systems definitely have intelligence, and that we, in the dominant culture, are only beginning to reacquaint ourselves with that. But, you know, if you spend any time with Indigenous people, that kind of observation, that close observation and care, will reveal a lot of this.

I was interviewing a Hopi farmer about dryland farming techniques, and he said, you know, 3,000 years of replication is a science. [LAUGHS]

Sooner or later, water always wins. So in the face of climate change, ecosystem collapse, water scarcity, we must shift our relationship with water. If we let go of our impulse for control and instead collaborate with water, we can win too. Climate change and the degradation of these natural systems that give us life can feel really overwhelming, but what I took away from meeting these water detectives around the world is that slow water projects are really empowering; it’s something that people can do in their own communities with their neighbors to make themselves, their neighbors, and their other-than-human neighbors more resilient to water extremes and climate change.

So I hope as you move through your own place, you’ll grow more curious about water, and ask yourself: What does water want?

Host: Erica Gies…

If you’d like to learn more about the extraordinary intelligence of life inherent in fungi, plants and animals, check out our Earthlings newsletter. In each issue, we delve into captivating stories and research that promise to reshape your perception of our fellow Earthlings – and point toward a profound shift in how we all inhabit this planet together.