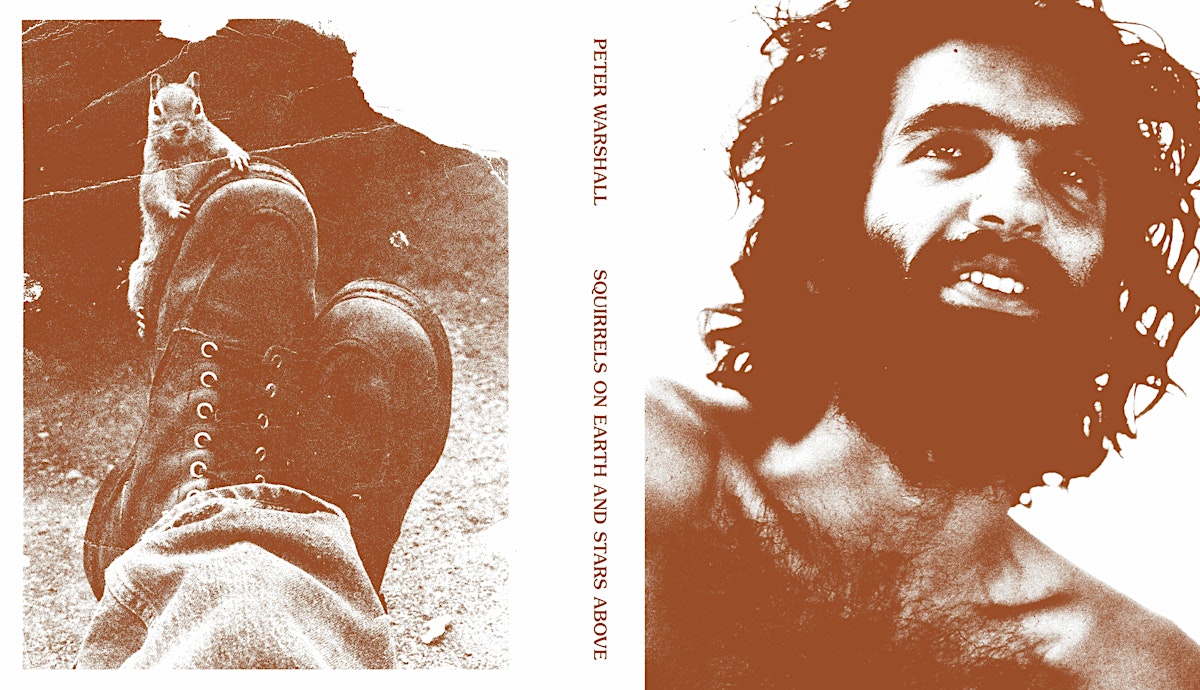

“Squirrels on Earth and Stars Above”: The Remarkable Legacy of Peter Warshall

Bioneers | Published: September 5, 2024 Ecological DesignNature, Culture and Spirit Article

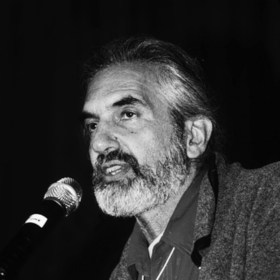

Peter Warshall was a great friend and ally of Bioneers with whom we collaborated on several initiatives, most notably the “Dreaming New Mexico” project. Peter was a genius in a number of fields and very, very far ahead of his time, but his legacy hasn’t been as widely recognized as it deserves to be, so we are thrilled that a new book about Peter has just been published, one that compiles a large selection of his essays and lectures as well as fascinating material from his archive to give a sense of the remarkable brilliance and dedication of this extraordinary human being.

His accomplishments ranged from studying with the legendary anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in Paris to being one of the most influential editors of those bibles of the counterculture, the Whole Earth Catalog and Whole Earth Review; to doing early, pioneering research on watersheds and septic and grey-water systems; to serving as Mayor of Bolinas, California; to groundbreaking work in Sonoran desert and Great Basin “sky island” conservation biology; to passionate activism on behalf of Indigenous land rights and wildlife protection in both the U.S. and in Africa, including vital work on creating wildlife corridors for the Northern Jaguar; to brilliantly original talks and writings on poetry, art, light and color…

Peter’s range of interests was astoundingly vast, but he was no dilettante: He was in several instances among the world’s leading experts in the fields he explored. There will never be another Peter Warshall, and it was a great privilege for us to have been able to know him, work with him and learn from him, so we are delighted to be able to present a few selected excerpts of this brand new, remarkable book that capture just some of his many facets and insights and the inimitable verve and passion of his style of thought and communication.

— J.P. Harpignies, Bioneers Senior Producer

The following excerpts are from “Peter Warshall: Squirrels on Earth and Stars Above.” (Edition Hors-Sujet, in collaboration with CMP Projects, Harvard University, 2024).

Peter Warshall (1943–2013) was a species of vertebrate who defied easy classification. In photographs, he is often either looking into a notebook or at some minute specimen cupped gently in the palms of his hands. Usually, there is a pair of binoculars hanging around his neck. Nick-named “Dr. Watershed” and the “Infrastructure Freak,” he referred to himself proudly as a member of the Maniacal Naturalist Society. A conservation biologist, humanist anthropologist, eco-tinkerer, and “biogladiator,” his pioneering contributions to ecology, public science, and what is now called “sustainability,” despite their significance, remain overlooked in mainstream histories of the environmental movement.

•••

When he passed away in 2013 from cancer, Peter had been at work for over a decade on a 3.8-billion-year history of the coevolution of solar radiation, photo-sensitive life, and color. The paintings of Cézanne, Klee, and others inspired many of his reflections on how shadows, tricks of optical perspective, and contrast figure centrally in the evolution of both human and nonhuman discerning awareness. In a letter to another human mentor, Frederic Jameson, he described the project as concerning nothing less than “the evolution of aesthetic zeal on this planet,” a history of “how the first pigments came to be,” of “light as solar radiance, filtered biospheric light, volumes of color space in various niches such as coral reefs and forest floors, light harvesting apparati of living creatures and the creation of the visual ‘imagination’ in the myriad ways patches of color turn into patterns.”

•••

Dził Nchaa Sí’an, also known as Mount Graham, is the tallest peak in the Madrean Sky Island Archipelago, about seventy miles north of Tucson, Arizona, a sacred site for the San Carlos Apache and also the home range of the endemic Mount Graham red squirrel. Throughout the 1990s and into the present, a long and bitter conflict over the construction of telescopes on the mountain has pitted environmental groups, various Native American nations, archaeologists, and scientists against one another over the summit’s fate. In 1986, Peter started working as a research scientist for the proposed astronomical observatory site in the Sky Islands—unique, vertically differentiated ecologies in Arizona and New Mexico. He became a significant player in what he called a “literal conflict between the heavens and the Earth,” spending several years fighting for the rights of a species that, previously thought to be extinct, he had helped rediscover in the 1970s. An affiliated research scientist at the University of Arizona during the controversy, he became the faculty’s most outspoken critic of the project and later the president of the 250-member Scientists for the Preservation of Mount Graham.

•••

[From a talk by Peter about the Great Basin’s “Sky Island” ecosystems]These mountains are like the Galapagos, except instead of being surrounded by ocean, they’re surrounded by desert. And since the glaciers have receded up into the North, these mountains have become isolated. As the glaciers receded, the deserts advanced. And you should think about how special this is—there are very few places on the planet where you have isolated populations of the same animals, of the same creatures, all going along in their own beatnik, eccentric condition, all going out and being experimental, both with their language, with their culture. All trying in very separate but similar cradles of evolution to evolve in new directions. And at some point, should the glaciers come back, should the deserts recede, should the grasslands and the juniper forests come back to the floor of the canyons and the valleys, all these creatures will meet again as they are able to come down. Then you’ll have a really interesting poetry festival in the Great Basin, where all those languages would have to meet.

•••

…the sky island (Mount Graham) is important because it’s the southernmost place of the spruce fir forest. It has the (Mount Graham) squirrel, the glacial features, it’s a relic Pleistocene Forest. A relic from 11,000 years ago. It has retreated to the top of the mountain, because that’s as close to Canada as it can get. It’s a relic forest, and that’s why it’s a cradle of evolution. There are nine plants up there known in no other place in the world; three species of mammals known in no other place in the world; two snails that have been isolated inside the rockslides that have been there since the Cretaceous seas receded. There are five to ten insects that we found in six weeks that no one has ever identified. Yet this is the forest that is about to be cut.

•••

The Mt. Graham squirrel’s special quality, or special kind of character, or ego, if you want to call it that, is its shapeliness. It’s the smallest squirrel of its kind in North America. It has a different tail size relative to its head. But what it really has is something that’s very old in North America, which is its need to keep on gnawing. If it doesn’t gnaw at something, then its bottom teeth will grow into its upper skull. If it has a wayward tooth, it can’t close its mouth because the tooth will not stop growing. This incredible persistence of its teeth to keep on growing, no matter what means it has to keep on chewing and gnawing and ripping and stripping, ad infinitum. This started 200 million years ago. This started in North America, in the Great Basin, where the first rodents and squirrels evolved and then covered the Earth. So, what we have here is a pretty amazing animal….its heart rate is 175 times what you’d expect for its size, which is about half a pound. It’s like a hummingbird, in a sense. I don’t know if you’ve ever listened to a hummingbird, but if you ever catch a hummingbird, hold it up to your ear. It goes, “brrrrrrr,” and that’s the heartbeat.

•••

[On light]

So, this is where we start. We start outdoors with the Sun. We’re all embedded in radiance. Everything on the planet is embedded in radiance. If we could see it, we’d be here among the sunlight, which is really starlight, it’s just a close star—and sometimes reflected moonlight. And we would feel around us a vibrational field going past us at all moments. This vibrational field would be very similar to the vibrational field of sound that we hear when our eardrums start to vibrate. There’s a single solar emitter in our world, the Sun. It sends out select groups of photons spiraling into space. As they spiral into space, they’re modified, both by their travel through space and by the biosphere, the layers of the atmosphere, stratosphere, and troposphere that surround this planet. Finally, all these vibrational fields get through the atmosphere, and they encounter Earth matter. And that is what we are, Earth matter. They enter our eye and our mind. There are 100 million cells just in your eyeball. Besides the brain, the eye is the organ with the most cells in the body. The whole of our lives are really attuned to this particular photon flux…

…Each photon has a personality in the way it spirals. Some spiral in long loops, and some spiral little loops. And that personality we call color. That’s why we use words like “tones” or “notes” of light. If we have an emptiness of photons on the Earth, or lack of photons, or lack of vibrations, we call that shadow and darkness. This is the vibrational field you’re living in every time, every day, from dawn, noon, dusk. The mind, even with its eyes closed, can create brightness and color without the Sun….There is a meditation, tonglen, where you inhale darkness and exhale light. We see our dreams in color, we see them in brightness. And if you have ever taken peyote, then you know that you can get incredible color patterns without having to look at the Sun or the Moon…

•••

Symbiosis literally means “together living.” Other ways of translating it would be biological companionship, or living embracing lives, or in-contact beings, or inside-each-other creatures, or, in Buddhist lingo, codependent-co-arising sentient existence. It’s the story of the evolution of interdependence. If any one of the two forms that live together disappears, the other disappears. Existential interdependence. It’s not a functional event like most marriages, where you can leave it and find another husband or wife, or another partner. In symbiosis, if one of you separates, both are gone. It’s a bit of a rock-and-roll romance. Symbiosis is like courtship and mating (as opposed to marriage) because it brings previously evolved beings together in new partnerships. Existential interdependence.

In short, symbiosis is perhaps the most self-propelling version of the creativity of life on this planet. Two disparate beings come together, and a kind of creativity is unleashed that propels life further and further….Life, first and foremost, is a very local phenomenon in that potential multiverse.

Both astronomers and Walt Whitman are sure that life is made of starstuff. About 4.6 billion years ago, a supernova blew up, and the pieces of that supernova became the materials of all living flesh. We are the cytoplasmic remnants of the supernova.

These excerpts have been reprinted with permission from “Peter Warshall: Squirrels on Earth and Stars Above,” edited by Parker Hatley in collaboration with Gregor Huber, Noha Mokhtar, Harris Bauer, and Diana Hadley, published by Edition Hors-Sujet, in collaboration with CMP Projects, Harvard University, March 2024. Assembled from his personal archive, the book showcases Peter’s innovative thinking on science, poetics, environmental citizenship, and the relationship between our species and the living planet.

For more information about the “Dreaming New Mexico” project, see project page 40 of the Bioneers’ 25th Anniversary brochure. See here for a detailed obituary of Peter Warshall.