In this special episode of the Bioneers, guest host Laura Flanders explores “Community Wealth Building,” a model that democratizes the economy, creates more cooperative businesses, better care for communities, and builds wealth for the many, not just the few. This episode features American political economist, historian, and author Gar Alperovitz of the Democracy Collaborative, along with India Pierce Lee about her work with the Collaborative in Cleveland, Ohio; and John McMicken, Executive Director of Cleveland’s Evergreen Cooperative Corporation.

This special Bioneers series is produced in collaboration with the Laura Flanders Show. For roughly a decade, Laura Flanders, a long time reporter on economic and social change, has been looking for alternatives. A new economic model that’s different from either state socialism or the kind of capitalism we’ve come to know. She found some serious experiments in what many are calling community wealth building from the U.S. to the U.K, the Netherlands and Australia. These economic models are also laboratories of democracy, because, of course, wealth is power.

This episode is part 1 of a 4-part series exploring how communities are working to transform their local economies by harnessing their assets, anchoring capital and resources locally to directly invest in that place and its people – from land to money and finance. Explore the full series here.

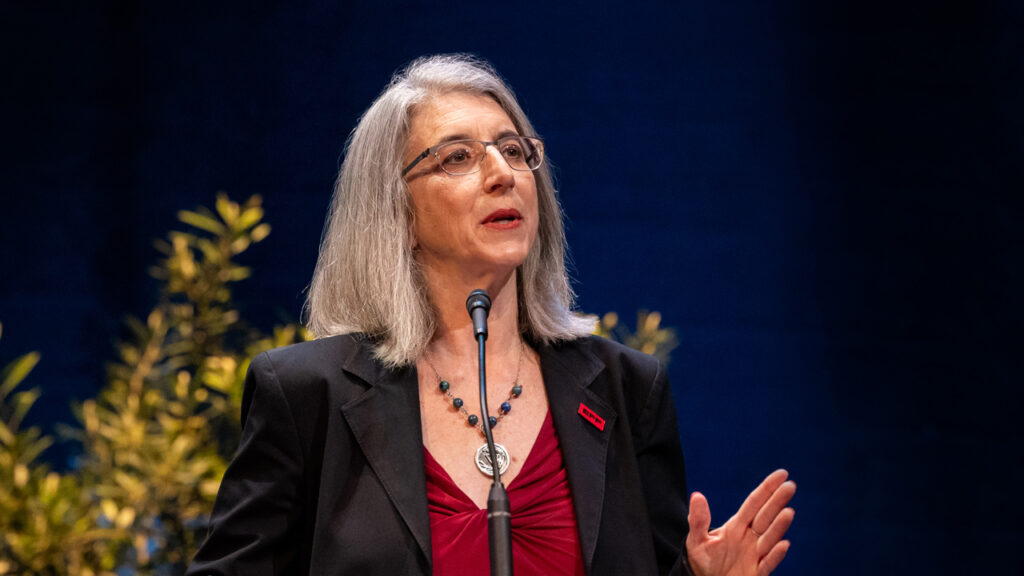

Guest Host

Laura Flanders is the host and executive producer of Laura Flanders & Friends, which airs on PBS stations nationwide. She is an Izzy-Award winning independent journalist, a New York Times bestselling author and the recipient of the Pat Mitchell Lifetime Achievement Award from the Women’s Media Center.

Credits

- This series is co-produced by Bioneers and Laura Flanders & Friends

- Laura Flanders & Friends Producers: Laura Flanders and Abigail Handel

- Production Assistance: Jeannie Hopper and David Neumann

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Senior Producer: Stephanie Welch

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

Resources

How to Make a Democratic Economy | Laura Flanders & Friends

Action Guide for Advancing Community Wealth Building in the United States | Democracy Collaborative

Gar Alperovitz – Replacing Corporate Capitalism: Why We Need a Next System | Bioneers 2018 Keynote

Our Economic Future: Achieving a More Equitable Society by Radically Rethinking Our Guiding Economic Ideas | Bioneers Reader

How to Make a Democratic Economy

Community Wealth Building: An Economic Reset

Full Conversation- Community Wealth Building: An Economic Reset

This is an episode of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature series. Visit the radio and podcast homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station and how to subscribe to the podcast.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

Neil Harvey (Host): Today’s economy is radically unequal, always in crisis, and destroying ecological systems we depend on. That’s no surprise, being that it’s organized to prioritize the interests of power, money and capital. How do we design a next economic system that centers the wellbeing, health and rights of people, communities and nature?

For roughly a decade, Laura Flanders, a long time reporter on economic and social change, has been looking for alternatives – new economic models that are different from either state socialism or the kind of capitalism we’ve come to know. She found some serious experiments in what many are calling “community wealth building” that are also laboratories of democracy, because, of course, wealth is power.

This special Bioneers series is produced in collaboration with Laura Flanders and Friends, the public TV and radio program that reports on social change experiments every week on PBS and online.

In this episode, we hear from American political economist, historian, and author Gar Alperovitz of the Democracy Collaborative, along with India Pierce Lee about her work with the Collaborative in Cleveland, Ohio; and John McMicken, Executive Director of Cleveland’s Evergreen Cooperative Corporation.

This is “Community Wealth Building: Democratizing the Economy”, with guest host Laura Flanders, on the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature.

Laura Flanders (LF): You don’t have to be an expert to know that the economy isn’t working for most people. Most of us are falling behind, running in place or working more than one job and a whole lot of us just aren’t happy.

When economists measure wealth – the U.S. is the top, or one of the top two wealthiest nations in the world, and has been for over 60 years. But measure happiness by looking at health, education, good governance, ecological diversity, or the ability to make really consequential choices in life – and this super rich nation isn’t even in the top ten.

So what’s the problem? Behind most social and ecological harms lurks an economic motive. So could there be a way to change those motivations by restructuring the economy, so as to put the health and happiness and rights of people, places and the natural world at the center?

One such approach is called “Community Wealth Building.” It’s a way to democratize the economy, create more cooperative and worker-owned businesses, care for our communities, and build wealth for the many in a way that’s good for us and the planet. One of the early thinkers behind this approach was political scientist and author/activist, Gar Alperovitz.

Gar Alperovitz (GA): Everybody knows we live in something called corporate capitalism. Now, that means there’s extreme concentration of wealth ownership. But the systemic problem is how you organize an advanced system so that you can reverse these trends with the institutions moving with you rather than against you.

LF: Gar Alperovitz has spent his entire life, coming up with ways to organize people, property and wealth differently – so as to serve society and the planet better than the way we do it now. As a young person, he worked in government on programs like the War on Poverty. He also worked with outside advocacy groups like the Institute for Policy Studies, which he helped to found, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign. Over and again, he saw how getting good politicians elected, and even good government programs enacted wasn’t enough. The way the economy worked simply skewed things in favor of the rich and powerful. Here’s Gar at a Bioneers conference back in 2012.

GA: One of the central issues is the distribution of income. There’s been a 30 year kind of flattening out of people working and not gaining at all. Most of the gains of—this is incredible, actually—most of the gains of the economic system over the last 30 years have gone to the upper top 1 to 2%. It’s extraordinary. That’s new in history.

And it tells you it’s a systemic problem, something deeply anchored in the nature of the system, not simply a political problem and not simply a policy problem, but something in the basement of the system is grinding out these kinds of long trends.

Other trends are also there, in terms of global warming, that one way or another the system is producing more climate changing gases, and they’re long trends of increase. We’re not altering them through the political system or the economic system. And it tells you that it’s a deep problem that has to be looked at in a different way than the usual political problem or the usual economic problem.

LF: In 2012, when Gar was speaking, 400 Americans had more wealth than the bottom 50% of us. By 2019, just 7 years later, three billionaires – Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and Jeff Bezos – had more combined wealth than the bottom half of the population – that’s 160 million Americans.

During the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis years between 2020 and 2023, that trend just got worse. Almost two-thirds of all new wealth created in those years – a whopping $26 trillion dollars – went to the richest 1%. And it’s not as if they gave back.

Between 1980 and 2018, the Institute for Policy Studies reported the taxes paid by America’s billionaires measured as a percentage of their wealth went down, decreasing 79 percent.

GA: It’s not only inequitable, that is there’s inequality in that, and obviously we know a lot about how that feels and what it means—but it’s politically very powerful. Most economic systems – whether it be Medieval systems or capitalist systems, socialist systems – who owns wealth often determines who has power.

Now, it’s common sense, but when you think about these numbers, it’s very difficult to have a democratic system because so much power goes along with that level of money.

It’s hard to adjust that politically because the roots of the power system are anchored in the very wealth that you’re trying to deal with. So it’s intractable. It’s systemic. It’s sort of built into the architecture of the political, economic system. Very difficult.

LF: So the problem isn’t shallow, it’s structural, discovered Gar. Not the bad actions of a few greedy individuals, but an entire system designed to benefit those who are already wealthy. And that made it hard to fix.

Without a more fundamental overhaul, wealth and power would keep concentrating, and militarism and environmental extraction would keep society and our planet on a devastating track. What was needed wasn’t a tweak – a bigger trickle of money, say, from the top to the bottom through charity or taxes or short-lived government programs that are always on the chopping block, but a healthier way to build wealth in the first place, a way that thinks more about consequence, for people and the planet and spread resources and power more evenly around.

But all that would require a next system. The good news is, many of the elements of that system are already in place…

GA: If you look at that concentration of wealth, what would be the alternative to it that was more democratic?

What do we know about democratic ownership of wealth in practical, American terms that might give us examples but also kind of the elements of a vision that might begin to point us towards a new direction? So, let me give you an example.

There are 130 million Americans who are members of co-ops and co-op credit unions. Now, that’s one person, one vote ownership of wealth, that’s democratic ownership of wealth. So that’s a very common American thing. People don’t even think about it when they go to the credit union or they buy at a co-op store or there’s REI and other places like that, that’s a different form of ownership. Not concentrated, it’s democratic.

Another one you might think about is—and the press doesn’t cover this very well – but there are 10,000 worker-owned companies in the United States – 10,000. There are about 10 million people working in companies owned by the workers, and it’s another form of democratic ownership, very common, very conventional. They’re much more productive, as you might expect when people have a stake in what they’re doing. On balance, they’re more productive, particularly when you have good training programs to go along with it, but there they are. It’s another illustration of democratization.

Municipal ownership is very common. People don’t quite realize this. Municipal utilities, for instance. Twenty-five percent of American electricity is produced “Socialist”—that is municipal owned electricity, plus co-ops, produce a quarter of all of American electricity now. There it is, kind of ordinary, conventional, often in very conservative parts of the South. So it’s another form of democratizing ownership of wealth.

There’s land trusts, which are another form of nonprofit ownership of land in order to do socially good things with it—housing and developing land. There are just dozens of these around, and they’re very American, and they begin to suggest a pluralist vision, very diverse, of different ways that we can begin to look at the ownership of wealth in a more democratic form, which not only may change the economics of it, but again, changing the power relationships because so much power goes along with who owns the wealth and trying to democratize power as well as democratizing wealth is the name of the game.

LF: From indigenous hunts and harvests, to collective colonial barn raisings, community based ways of getting things done should be as much part of the American story as the fictitious go-it-alone Horatio Alger myth. Under slavery, for example, Africans pooled funds to buy people’s freedom and Mutual aid societies paid for emergencies like ill health and burials.

Later, organized labor groups, such as the Knights of Labor and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, promoted worker-owned cooperatives as a way to keep resources and money in workers’ hands. And during the Great Depression, people came together in co-ops as a way to pool assets and cut costs to survive. In the 1960s, solidarity economics was a way to build Black, Indigenous and Chicano independence and power.

So too, today, coming together in cooperatives is bringing down the price of food, loans, equipment, and all of the things individuals have a hard time affording alone. Consumer coops like the well known Park Slope Food Co-op in Brooklyn, New York, enable members to buy groceries at lower bulk prices in exchange for contributing hours of volunteer labor.

Worker co-ops such as the Cooperative Home Care Associates in the Bronx enable typically low-income home-health aides to negotiate contracts collectively and create training programs designed and led by fellow home care workers. Adria Powell serves as President and CEO.

Adria Powell (AP): So Cooperative Home Care Associates is a worker-owned cooperative, which means that anyone who works for the cooperative can also be an owner, but you’re not required to be an owner. We each are allowed to buy one share, which entitles us to one vote. So it’s completely democratic participation.

When you are a worker owner, you have the right to run for the board, and the board of directors here at Cooperative Home Care is made up of eight elected worker owners, which are home care workers. And so when we are profitable, all worker owners have the right to share in that profit on an equal basis. So there is the opportunity to vote for one’s own financial interest.

It also builds a sense of community. It empowers workers, worker owners to be more committed to the organization. There’s a sense of pride in terms of the work that they’re doing and wanting to see Cooperative Home Care be successful.

It’s not just about profits. It’s also a way to invest in our local economy. Our workers come from the areas that we serve. You know, our clients they live in the same areas in the Bronx, in Manhattan, what are traditionally low income areas.

And so by being a for-profit, we’re investing back into our community. When people are earning wages, collecting dividends, it’s going to stay within our community.

LF: In a cooperative, every member has one vote. Together they own the business, come up with the rules, and set the wages and share in its success. Cooperatives also commit to helping one another.

So it was in 2020, when the Covid pandemic hit, Opportunity Threads, a sewing cooperative in South Carolina, organized with the Carolina Textile District to re-tool their production in order to sew masks. That pivot enabled them to keep Cooperative Home Care Associates in the Bronx supplied with Personal Protective equipment, when there were few masks to go around for healthcare workers on the front lines.

Cooperation, and putting community interests first, are core concepts to Community Wealth Building. To counter corporate globalization, which extracts wealth from a place, community wealth building approach, relocalizes wealth. To reverse the extreme concentration of wealth in the hands of a few, community wealth building strategies work to distribute assets and wealth widely, and democratize business structures so as to share decision making and value labor and land. In contrast to counting on short term profits, community wealth building takes the long view about what is best for a healthy economy, people and planet.

So where do we go from here? Again, Gar Alperovitz.

GA: So the system problem, not only how do we get from here to there – what is the nature of the design that you would actually want to live in? Who would own things? Where would the power come from? Would it be an expansionary system? Corporations have to expand. They’ve got to keep reporting more profits, and that has environmental implications for big corporations. So what is the nature of the design? This is our problem. What would it look like in the ideal? And then how do we get from here to there? And what kind of models can we experiment with?

LF: To advance the practical work, in 2000 Alperovitz founded the Democracy Collaborative with his colleague Ted Howard. They call it a “think-and-do tank”. Theory is useful they say, but experiments making transformation visible are even more important.

One of the game-changing experiments The Democracy Collaborative has been part of is the Evergreen Cooperatives Project in Cleveland, Ohio.

GA: This is in a very poor neighborhood, 40,000 people, mostly black, average unemployment 20%, family income average $20,000. Very poor neighborhood. In the middle of that neighborhood is the Cleveland Clinic, Case Western Reserve University, and university hospitals. All three of those institutions – Medicare, Medicaid, education money – have a lot of taxpayer dollars in them. They buy a lot of things just to exist, and they can’t move. They are so-called anchored, because they are a huge investment of capital in those buildings and all that facility. This is a technical term these days – anchor institutions.

So one of the designs that we’ve developed, and this is one of many – there are a lot of people experimenting with this – is could we use the purchasing power of these big institutions, focus it on this community, establish a community-wide nonprofit corporation to benefit and reflect the community as a whole’s interest, and attach to it worker-owned companies. That is a systemic design in miniature.

LF: When we return, we’ll hear from one of the Democracy Collaborative’s key collaborators in the Evergreen Project, India Pierce Lee, who was then at the Cleveland Foundation. And from John McMicken, the executive director of Evergreen, on how the company helps its employees buy homes.

I’m guest host Laura Flanders. You’re listening to the Bioneers…

LF: Anchor institutions, deeply rooted in place, such as universities and hospitals, are key to community wealth building.

Starting in 2008, the Democracy Collaborative partnered with several of Cleveland’s most prestigious anchor institutions in order to develop a Community Wealth Building approach to buying stuff. Instead of contracting with a far-off, non-union laundry service, for example, the Cleveland Clinic agreed to contract with Evergreen, a cooperative laundry owned and run by its employees, the vast majority of whom are African-Americans living nearby.

Cleveland at the time was anything but evergreen. Having once been one of the great U.S. industrial cities, attracting workers from around the world and across the country, Cleveland’s boom began to slow in the 1960s and over the next three decades, the city lost 24 percent of its population.

By 1975, Cleveland ranked in the nation’s highest 20 percent in terms of poverty, unemployment, dilapidated housing, municipal debt and violent crime. As the century drew to a close, globalization, white flight and years of budget cuts only made things worse. And it wasn’t arbitrary who was left behind. Here’s India Pierce Lee.

India Pierce Lee (IPL): We have all the disparities, I think, but what people have finally begun to acknowledge since 2020 that a lot of us have been fighting for decades is that understanding the root causes of every issue is tied to systemic and institutional racism. I mean, we talk about wealth building, we talk about building equity, we talk about disinvestment, but then we have to look at the policies, the practices that have plagued the red lining in our communities that have caused this decades and decades. And now we’re trying to swim our way out of.

LF: India Pierce Lee worked on community development for a community foundation, the Cleveland Foundation for 16 years, starting in 2006. Community wealth building, she says, provided a way to address historic wrongs, methodically, through policy, as methodically as the wrongs of systemic racism were committed in the first place.

I spoke with India Pierce Lee in 2022.

IPL: So we’ve been at this work now about 17 years. And over time we have continued to evolve, add new partners, but then getting people to acknowledge that you have to pay people what they’re worth, right, to create the kind of wealth. You know, we have this glut now people leaving jobs and not coming back. We need to acknowledge that people need the same basic human needs. It’s not about a right. It should be that’s everything for everyone, healthcare, good housing, you know, good school systems. But really looking at how we democratize and educate our community, so that they have ownership in the community. And we’re doing some of those things on a small scale, but it’s starting to take hold not only here, but across the country, creating land trusts.

We have a Black Futures Fund that we created to support small, non-profit, Black-led organizations doing great work in the community, touching the people where they are, but it also means that we have to change the way we do business. We have to figure out how we build and share power, and co-create with the individuals we’re working with to make the kind of changes that benefits them and not us telling them what they need.

LF: By putting community wealth building at the center of their concerns, the Evergreen Project was able to do more than just create jobs. The project prioritized hiring the most vulnerable – including people returning from prison and jail – and used the assets of the business and its relationships with other institutions to help people find and keep housing, so as to build wealth of their own. I had a chance to talk with the Executive Director of the Evergreen Cooperative Corporation, John McMicken, about the company’s accomplishments thus far.

John McMicken (JM): So you have employee-owners, frontline production workers, if you will, who are serving on our boards, and advising the company as to larger decisions that need to be made. You know, from there, we have a couple of other very unique programs that we’ve been working on over the past several years. One is a very successful home buying program. And so we’re giving worker-owners access to the financial literacy training, the credit building necessary to actually buy a home. And we’ve been able to structure those financially so that their mortgage payments can be payroll deducted if they so choose. And most importantly, the transactions are built in such a way that the employee-owner is able to pay the mortgage off in full within five years. So it’s a really, really special and in many cases life-changing program.

Everything we do we do to serve the neighborhoods in and around Cleveland, Ohio, specifically what’s referred to as the Greater University Circle Initiative. We’ve partnered with our anchor institutions there, our hospitals and universities to incubate new businesses at scale. So these are larger, commercially viable businesses that then begin to provide goods and services back to not only those larger institutions, but any other customers that we develop along the way. But again, in doing so we are structuring them so that no less than 80% of the equity of these companies is held by the employees and will always be held by the employees.

So there’s some very neat mechanisms put in place to ensure that there’s no change to that structure, there’s no dilution to that structure over time. So 50 years from now, hopefully these three cooperatives and more are still in business. And if they are, they will still be at least 80% owned by the full-time employees.

LF: Since Evergreen launched its first cooperative business in 2009, the company has overcome growing pains, attracted multiple contracts and expanded its staff to nearly 200 people. Today Evergreen is not just a laundry service, it’s a parent company responsible for launching other new employee-owned businesses and helping privately owned small family businesses convert to employee ownership with its own dedicated loan fund.

Now several states are advancing employee ownership legislation that would make it easier for worker-owned businesses to get loans and technical assistance and government contracts. Many of these are also green businesses, another core tenet of community wealth building.

Can all these democratic experiments be woven together to create a “next system” – one that creates wealth that’s deeply rooted, widely shared and in the hands of local, forward-looking residents committed to a liveable planet and thriving local economies into the future? That’s the essence of community wealth building. It won’t be easy, but it’s the work of our times, believes author, activist Gar Alperovitz.

GA: What is it I can do tomorrow to change the system? Or more specifically, to lay down an irreversible foundation in projects, in organizing, in politics, etc., that establishes the basis for a transformation. That’s not saying tomorrow I will change the system. My heroes are the Civil Rights workers in Mississippi in the 1930s. We don’t know many of their names. They laid the foundation for the 1960s. That is where I think we are and to see ourselves in that role, I think is empowering, and we’re seeing a lot going on.

LF: The Democracy Collaborative produced a Community Wealth Building Handbook recently, a kind of field guide for policymakers, advocates and engaged citizens. We’ll post a link on this episode page. Go to Bioneers.org/radio.

These laboratories of economic democracy are spreading, maturing and reaching critical mass. For The Bioneers, I’m Laura Flanders.