In this episode, award-winning lawyer and climate justice organizer Colette Pichon Battle lays out a bold vision for a new organizing project designed to model bioregional democratic climate action. The aim is to transform the Gulf South and Appalachia away from the lethal matrix of fossil fuel extraction and extractive economics. Instead, the regional vision is for a regenerative future of clean energy democracy, and an equitable, inclusive economy.

Featuring

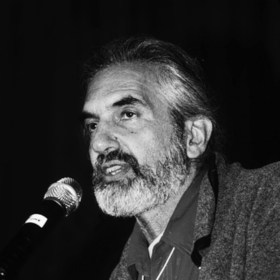

Colette Pichon Battle, a generational native of Bayou Liberty, Louisiana, is an award-winning lawyer and prominent climate justice organizer. After 17 years leading the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy, she co-founded Taproot Earth to create connections and power across issues, movements, and geographies.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Kenny Ausubel

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Songs in this Episode: ‘Good Morning New Orleans’ by Kermit Ruffins; ‘What Goes Around Comes Around’ by Rebirth Brass Band, provided by Basin Street Records in New Orleans, Louisiana

Resources

Colette Pichon Battle – Expanding Our Movements for Climate Justice | Bioneers 2024 Keynote

“Let’s Get Behind the Frontlines” with Colette Pichon Battle | Audio Excerpt

From Climate Crisis to Climate Justice | Bioneers Newsletter

This is an episode of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature series. Visit the radio and podcast homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station and how to subscribe to the podcast.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

Neil Harvey (Host): In this program, award-winning lawyer and climate justice organizer Colette Pichon-Battle lays out a bold vision for a new organizing project designed to model bioregional democratic climate action. The aim is to transform the Gulf South and Appalachia away from the lethal matrix of fossil fuel extraction and extractive economics. Instead, the regional vision is for a regenerative future of clean energy democracy, and an equitable, inclusive economy.

I’m Neil Harvey. This is “From Scarcity to Abundance: How Collective Governance Can Transform the Climate Crisis”on the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature.

Host: In August 2005, when Hurricane Katrina made landfall, it was the 4th most intense Atlantic Hurricane ever to wallop the contiguous United States. Mother Nature stopped knocking and simply blew the doors off any doubts about the ferocious onset of climate disruption.

The message was crystal clear. When we fight nature, we lose.

There was also a cruel poetic justice in play. Katrina’s ill winds souped up on fossil fuels struck right at the pumping technological heart of the Gulf South’s petrochemical industry. Katrina further unmasked the injustice that poisons society as surely as the torrent of crippling pollution did.

It’s an open secret that poor people and people of color are relegated to live amid the worst environmental hazards of industrial civilization.

While an inept, cynical federal government staged damage-control press conferences, compassionate person-to-person daisy chains surged into action. They showed that true social security depends on community.

But Katrina was just a coming attraction of the new world disorder: escalating climate disruption and the clash between the state of nature and the nature of the state.

Behind this disorder lurks a purposeful ideology: “disaster capitalism.” Capitalize on the chaos of disasters and exploit it to further concentrate wealth and power.

But today, nearly 20 years after Katrina, the ground truth is that a uniquely diverse and widespread resistance is arising from the frontlines to address the climate crisis and to challenge the corporate race to the bottom to loot the commons.

At the forefront of that resistance is the award-winning lawyer and climate justice organizer, Colette Pichon-Battle.

Colette Pichon-Battle (CPB): There are several things from Hurricane Katrina that people still don’t get. The first, most obvious, thing is our continued extractive of fossil fuels is accelerating more extreme weather, and we have not reduced our extraction, we’ve increased it. We have not reduced our greenhouse gas emissions, we’ve increased it. And this is since Katrina, this is knowing what can happen, this is knowing what’s going to happen. There cannot be any more drilling of fossil fuels.

So I think that’s the biggest thing, that folks don’t understand Katrina as an extreme weather event accelerated by the extraction of fossil fuels from the planet. The oil companies knew it. The oil companies hid it. That has all been uncovered. It is clear, it is the basis of lawsuits everywhere. This is just like tobacco. They knew it was going to kill us, and they did it anyway.

I think the other thing that people don’t understand is that extreme weather events like Katrina are happening everywhere.

If a regular person, blue or red, heard the truth about what was happening globally, this would not be a difficult discussion on climate change. They know it. They know it and they see it, and it would be empirical data that they would add to what they are seeing in their own backyards.

The rain is not coming at the right time in Louisiana, or it’s coming too much, when it’s not expected. The Mississippi River’s at an all-time low, an all-time low to where saltwater intrusion is coming up the river and threatening drinking water in South Louisiana where we’re losing land at one of the fastest rates on the planet. Come on! This is not a red or a blue conversation. Something is happening, and we’ve got to do something about it, and it is not only important when it hits the coast of Louisiana. It is important everywhere, every day.

And it is our extraction. It is our consumption. It is the American consumer, and the American companies that press and market consumption that’s causing the imbalance. And the rest of the world is waiting for us to wake up to that. Katrina was supposed to be a wake-up call. Unfortunately, 19 years later, folks have gone back to sleep.

Host: In the long tail of Katrina, not only were devastated Black and Indigenous communities left out of federal recovery programs – hundreds of thousands of residents had to flee the area as climate refugees in what amounted to a new diaspora. In response, Colette Pichon-Battle abandoned her private legal practice to create the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy. For the next seventeen years, she would work to provide relief and legal assistance to her beloved Gulf South community and the lands she loved.

Over time, she saw that much larger political-economic systems were at work. Colette spoke at a Bioneers conference.

CPB: Here’s what I know to be true. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, everything broke. Everything. The governance system went all the way down from the top to the bottom. There was no system of governance. And at that point you realize how military control happens. You realize how chaos happens. We weren’t under an official state of emergency that allowed for chaos, but it was pretty chaotic.

And on top of all of that for the two to three years that followed, there were many elections. And what was interesting was that we had hundreds of thousands of people in over 50 states who needed to vote in local elections, and we had to figure out a process of literally getting people back home to vote, and that we had to do that when there was no place for them to live or be.

This was the moment where I realized the climate crisis – which was much bigger than a disaster, a storm – this thing is going to knock out all systems of governance. This is where tyranny can take hold. This is where the bad things can really root themselves.

I often listen to folks making five-year plans about the legislation we’re going to pass, about the folks we’re going to get elected, and I try to just keep my face straight and not say the words that I actually believe in my heart to be true, which is: this system will go down and what do we have in place, ready?

Host: As the iconic climate scientist James Hansen has summed it up, “It’s very hard to see us fixing the climate until we fix our democracy.”

Indeed, Colette witnessed first-hand the traumatic effects of the economic shock doctrine that transformed the Gulf South after Katrina. Colette witnessed first-hand the traumatic effects of the economic shock doctrine that transformed the Gulf South after Katrina.

CPB: The big picture 19 years later after Katrina is, you know, a lot of the children impacted by Katrina are now young parents. I’m watching all of them suffer with a level of mental health challenges—PTSD, anxiety, depression—at levels that if you know anything, and you just look at who we’re talking about, you know that this is what happens to children in that trauma. They’re not functional. Many of them are coming for jobs now. They’re really struggling.

You know, the truth is that while the populations of New Orleans and places where I live, Slidell, just outside New Orleans on the Mississippi border, Biloxi, those population numbers have come back but they’re not the same people. The culture of those places have changed significantly because the people who held the culture aren’t there anymore, and the culture that was held by those folks was held in a collective. So even though those folks exist in other places, they don’t exist in their network anymore. And so the culture that made Louisiana so rich, so deep is just changing.

Host: The chaos, desperation and fear provoked by disasters provide perfect political cover to deploy extreme, top-down social and economic policies that are wildly unpopular.

Disaster capitalism seized its golden Gulf South opportunity. Along with the cultural clear-cut that Katrina allowed, there followed a fire sale on distressed real estate, which would soon result in gentrification.

Big money flooded the zone to elect and appoint corrupt crony politicians to hijack democratic governance. They moved quickly to extract wealth for the few and guarantee business as usual for the fossil fuel industry.

This unnatural disaster left people dazed and stranded – trying to survive amid enforced government austerity, radical instability and a dire lack of infrastructure and services. The Gulf South would come to resemble a failed state.

CPB: We lost our entire teacher class. It was almost all Black teachers. They fired all the teachers after Katrina and forced them to retirement, and then replaced them with Teach for America folks who came from all over. And so what was a Black woman-dominated field is now a sort of experimental place for folks from all over to come teach in New Orleans for a little while, you know, and like, get your experience, like a Peace Corps. They took down the public school system. There is no public school left in New Orleans, they’re all charter.

Public monies are going to charter schools that literally last, I think, an average of two years, and then they switch schools. Yeah, so, what kind of education do you think these kids are getting? It’s terrible. If you thought it was bad before, it’s bad now. There’s no accountability system.

The public health system is gone in the whole state of Louisiana. Bobby Jindal did that, our former governor. And now public monies that should have gone to a public health system that allowed people to have the care they need now go to a public/private partnership of Catholic hospitals that can refuse care based on Catholic teachings, if you get my meaning, especially for women. Think about that.

These are public systems meant to help the poorest people, and the poorest people in the South aren’t just Black. The only thing they have more than poor Black people in the South is poor white people in the South. And those systems are down.

And I think it’s fueling the rage. The poor white people don’t know why things aren’t working, and they’re being told to blame the Brown and the Black people.

Host: The real issue has never been about dismantling so-called “big government.” The battle is always about whose interests government serves: In this case, the care and feeding of giant corporations and the politicians who serve them…

Colette Pichon-Battle came to understand climate chaos as the result of this political crisis. She turned to community organizing. She looked to the communities themselves, who were actively working to devise real solutions to meet people’s real needs. It starts with recognizing that either we stand together, or we fall apart.

CPB: And I’m going to tell you, you’ve got to go through a climate crisis, you have to go through a disaster to understand what will break down and what will not last and what’s not real, even.

And let me tell you, in Katrina, money wasn’t real. The banks were closed. There was nothing you could use your money for. If you didn’t know how to fish, you were in trouble. If you didn’t know where that water, where the aquifers were, you were in trouble. Everything was down. And these are the moments you realize that half of this stuff is made up, right?

In order for the capitalist system to work, scarcity is a fundamental understanding of that system. If we break out of scarcity into abundance, we necessarily have to change an economic system that’s meant to just extract value for the few. And this system is something that we’ve all got to be able to challenge. Now, how do you challenge a system that you’re maintaining? This is not going to be easy. This is going to make a lot of people who understand security as the number of dollars in their bank account to understand security as something much different – a collective of community that people who show up for each other.

But what if we don’t know each other? What if we don’t trust each other? How do you make that shift? We can’t really fathom what it is to be in a collective, what it is to not have. But to have someone bring a plate to your house and say, here’s your dinner. There are communities and groups of people who live like that, who believe if you are in the community, you shouldn’t be hungry. If you’re in a community, you shouldn’t be without a place to dwell.

What kind of society do we live in where we think it’s okay for people and children to be hungry with this kind of wealth? This is going to take not just an abundance of courage, but an abundance of love and humanity for us to get back to our own balance so we can balance the planet.

Host: For Colette, that balance was deeply woven into her own upbringing.

CPB: There’s a really short moment in climate disaster where we all come to remember that very basic principle, which is that we need each other. And we do.

And individualism makes us believe that there’s such a thing as individual success. You know, you got your A on your test. You got your scholarship. You got your diploma. You did it alone. No way. No way.

And I come from a community that will absolutely not let you think like that. My mom will tell you in a second, “We did it! We got a diploma! We got our law degree, we’re barred!” And when I was barred, my entire community came. I had 30-something people from the Bayou at the Supreme Court in Louisiana watching me get sworn in. They contributed to me, and I contribute to a whole, and we’re all together surviving, and that’s the only way we can.

Host: When we return, how Colette Pichon-Battle is changing the terms of engagement by creating a bioregional, solutions-based, collective network of frontline communities. They believe overcoming the climate crisis requires creating genuine democracy. I’m Neil Harvey. You’re listening to The Bioneers…

Host: Studies of resilient communities that rebound from disaster show that government works best when it’s closest to the people it serves.

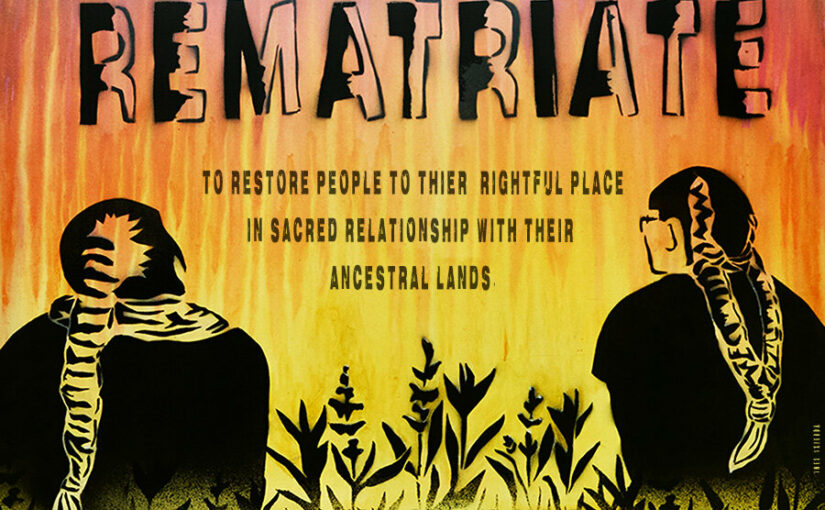

In that light, in 2022 Colette Pichon-Battle co-founded the nonprofit network called Taproot Earth. The goal is to surface solutions from the ground up and to build power across a bioregional network of communities and movements.

Colette launched a series of convenings to hear from the communities themselves and to connect them with each other. They decided their shared goal was to transform systems of governance. That meant moving away from propping up extractive corporate and fossil fuel economies and moving toward democratic self-determination for the greater public good of people and nature. They expanded the map beyond the Gulf South to include Appalachia, and are now working to create a global stance.

CPB: Our work is really to build formations that can govern themselves, and to build those formations from the frontlines upward. We focus on the Gulf South, which is Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, and Puerto Rico. We share a water, and so that is how we—we use, some might call it a bioregion, we call it watershed organizing. Take off those borders and think about the natural systems that we share. We share that gulf. We share those waters. We share the realities of a particular history in the South.

We also focus on Appalachia, which brings us into not just the Ohio River Valley but into the sort of Appalachia Mountain chain, but all the states that touch that—the Carolinas, some of the Georgia south, of course, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, West Virginia. And, again, we’re working in these areas that are the energy sources for this country. So oil and gas and coal is the Gulf South and Appalachia.

I’m learning more about the impacts of the climate crisis and the fossil fuel industry in particular in Appalachia. And this has been really interesting to me because Appalachia is where we find very large numbers of poor white people. Right? Because some folks can’t hear…they don’t want to have a conversation about what Black people deserve and how marginalized Black people are. They just turn off to race. And so if you go to a place where the mainstream aversion to race can be avoided, you go to Appalachia, and these are poor white folks who are, you know, beholden to the industry that is killing them.

But what I’ve been watching, especially with mountaintop removal and coal extraction, is how much freshwater is being lost, and how many trees are being lost. And when you watch the floods in Kentucky that happened a couple years ago, you didn’t just see flooding, you saw a terrain that had been so changed that the flooding was uncontrollable.

And that’s not to mention that the water that’s going downstream is now poisoned, because the byproducts of coal extraction, you know, the water flows over that, and they can’t even have access to water.

So, you know, I think Appalachia’s a place to look. And if you think about the Gulf South and Appalachia, you get to this nation’s energy regions. We are oil and gas, and coal and gas. We are the poorest, least educated people in this nation. And in those places, extraction is not regulated, not enforced, and the industries that are in charge there control the governance, the finance, the education system, the health, they control the whole thing. It is in these places you see an absolute alignment of both corporation and state.

Host: But for Colette, addressing these kinds of burdens of history also requires a global perspective. That map shows the heavy footprints of colonialism and slavery.

CPB: And we also work in the Black diaspora, and we define the Black diaspora as any place where Africans were and were taken from and brought in the Transatlantic slave trade. And so we work absolutely on the African continent, but also in the U.K., Canada, the U.S., the Caribbean, Latin America, South America. These are places where Black folks are, and that’s where we want to do our work.

And so building formations, both domestically in the U.S., but also globally. We have our Global Black Climate Leaders network. It’s called Taproot Noir, and it is all Black from the Black diaspora.

We have a Gulf South to Appalachia formation that runs those 17 states, and it’s all frontline people who are coming together to say we understand what’s happening and we have solutions. We’re not an organization focused on, you know, tearing down or dismantling the system, although we are in deep solidarity and support for those organizations whose job that is. We want to be ready with some solutions, and we want to be ready with not just ideas, but actually piloted projects that come from the frontline, so that when someone has the audacity to tell us that they understand what we’re saying but there’s no proof that we can make change, we say we have the proof. And we are starting to really show that in the world. And I’m really excited about that.

Host: Following the series of dynamic Taproot Earth convenings, the communities translated their focus on transforming current systems of governance. The network identified six “pillars of climate justice” which include: water, energy, land, labor, economy and democracy.

The network went on to identify an initial set of specific interventions that can be replicated at local, state and regional levels:

- Make the energy grid reliable, sustainable and publicly accountable;

- Restore the land and repair legacies of harm;

- Ensure equitable residential access to clean energy and water;

- End prison labor exploitation;

- And fund community-led climate planning and ensure fair disaster response.

The goals for Taproot Earth’s Liberation Horizon are:

- to replace disposability with sustainability, authoritarianism with collective governance and privatization with stewardship.

- to leverage these replicable models into region-wide transformation by 2030;

- and to build internal infrastructure for leadership development.

CPB: And so we’re going big. The vision is large. It’s taking a lot of courage. We’re building a team. We’ve got a just transition lawyering network, and that lawyering network works in the U.S., and it’s specifically to flank the climate frontlines. We’re building these formations that govern themselves. And in seven years, when we finish, they will stand on their own. You know, Taproot Earth wants to be able to say: Here are the models, and they’re coming from the frontlines. And they always were. And they always can. So let’s put our investment, our time, our energy there, and let’s get behind the frontlines.

Host: Colette says these frontline, localized and regional models represent a much bigger enterprise.

CPB: And there’s got to be something much deeper that we’re fighting for, a deep engagement, which is you have to press a button every four years and the day after you press a button, you got to go to the council meeting and the day after the council meeting, you have to sit with your neighbors and talk to them and ask what’s going on. And the day after that, you’ve got to keep being in conversation and relationship because democracy and engagement is not once every four years pressing a button for someone you don’t know. It’s something much deeper than that. It’s like a floor that has to be constantly swept, right? It’s like a thing you have to constantly engage in.

We have the opportunity in this climate crisis to re-envision what a democracy could be. And I think we’ve got to do that relatively quickly and we’ve got to have, I think a real acknowledgement that to vision, to live and to manage a democracy is work. And we’re pretty lazy. We’re pretty lazy. This representative government that we got, it feels good to us because you sort of like, I don’t really have to care. I don’t really want to talk about it today. But that’s not what this is. If we want to be in a unified struggle for a really good life where we all thrive, then we’re going to have to put in equal work to manage, to envision and then manage a new democracy.

Host: Colette Pichon-Battle is clear-eyed about the daunting odds of taking on the corporate state and centuries-old burdens of history.

CPB: And you could really get a place of nihilism and defeat. You could really get a place of just, why bother? And I get that question all the time. Colette, if you know your community is going to be lost no matter what, why are you fighting? And, you know, I say to them the struggle that I’m fighting inside of did not begin in 2005. There’s a Black liberation struggle that has been going on for a very long time. I think it’s true of so many people. We’ve been fighting the whole time. I did not find—begin a fight in 2005, I joined a long-term struggle for liberation for all people.

We think that we can catalyze people into being the best that they can be, into trying things that they would never try; into reaching levels of courage that they never thought they would have to reach, for the benefit of others, and for people they were never told to value. I think we can reach that…

There’s a liberation horizon, it’s 2030, and that’s where Taproot Earth really wants to help shift the social understanding. We don’t have to give into this. We can choose to fight. We can choose to create. We can choose to love. We can choose to move from scarcity and fear to love and abundance, and that’s what 19 years of Katrina has taught me. That’s where we need to go. And we want to invite everyone to join us toward that liberation horizon, 2030. Taproot Earth.

Host: Colette Pichon Battle… “From Scarcity to Abundance: How Collective Governance Can Transform the Climate Crisis”