Book Giveaway Official Rules

1. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. VOID WHERE PROHIBITED OR RESTRICTED BY LAW. THE SWEEPSTAKES IS SPONSORED BY BIONEERS/COLLECTIVE HERITAGE INSTITUTE, 215 LINCOLN AVE #202, SANTA FE, NM 87501.

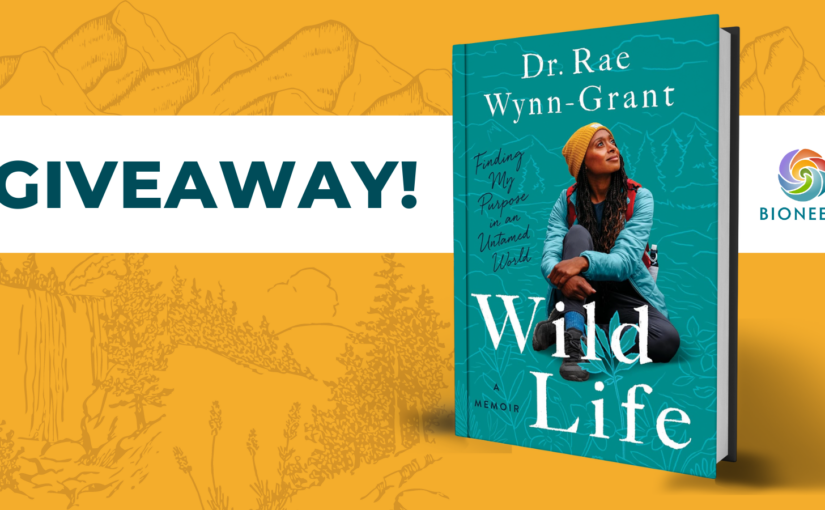

2. Entry Period: “Book Giveaway: Wild Life by Dr. Rae Wynn-Grant” (the “Sweepstakes”) commences at 12:01:01 AM (PST) on May 13, 2024, and ends at 11:59:59 PM (PST) on July 12, 2024 (the “Sweepstakes Period”).

3. Eligibility: To take part in the Sweepstakes, participants must be legal residents of the United States or Canada (excluding Quebec, where the promotion is void), and at least 18 years of age at the time of entry. Employees (and their immediate families, i.e., parents, spouse, children, siblings, grandparents, stepparents, stepchildren and stepsiblings) of Bioneers and its giveaway affiliated partner companies, sponsors, subsidiaries, advertising agencies and third-party fulfillment agencies are not eligible to enter Sweepstakes. By participating in this Sweepstakes, entrants: (a) agree to be bound by these Official Rules and by the interpretations of these Official Rules by the Sponsor, and by the decisions of the Sponsor, which are final in all matters relating to the Sweepstakes; (b) to release and hold harmless the Sponsor and its respective agents, employees, officers, directors, successors and assigns, against any and all claims, injury or damage arising out of or relating to participation in this Sweepstakes and/or use or misuse or redemption of a prize (as hereinafter defined); and (c) acknowledge compliance with these Official Rules.

4. To Enter: Enter required information in the Giveaway Signup form above during the eligible period. Contestants may only enter the Sweepstakes once. If multiple entries connected to a single person or email address are received, only one entry will be eligible. All entries submitted in accordance with these Official Rules shall be hereinafter referred to as “Eligible Entries.”

5. Prize Winner Selection: 5 winners will be randomly selected from among all eligible entries received at the end of the stated period, or within a reasonable time thereafter. Winners will be responsible for all U.S. and State taxes and/or fees. No transfer, substitution or cash equivalent of prizes permitted. Winners will be notified by email. Sponsor is not responsible for any delay or failure to receive notification for any reason, including inactive account(s), technical difficulties associated therewith, or winners’ failure to adequately monitor any email account. The winners must then respond to Sponsor within 48 hours. Should a winner fail to respond to Sponsor, Sponsor reserves the right to disqualify that winner and select a new one in a second-chance random drawing.

Prize and estimated retail value: One hardcover print copy of Wild Life (estimated value: $24.99)

6. General Prize Terms: The value of Prizes may be taxable to Prize Winner(s) as income. All federal, state and local taxes, and any other costs not specifically provided for in these Official Rules are solely the Winners’ responsibility. Sponsor shall have no responsibility or obligation to a Prize Winner or potential Prize Winner who is unable or unavailable to accept or utilize the Prizes as described herein. The odds of winning the Sweepstakes depend on the number of Eligible Entries received. Noncompliance with any of these Official Rules may result in disqualification. ANY VIOLATION OF THESE OFFICIAL RULES BY A PRIZE WINNER OR ANY BEHAVIOR BY A PRIZE WINNER THAT WILL BRING SUCH PRIZE WINNER OR SPONSOR INTO DISREPUTE (IN SPONSOR’S SOLE DISCRETION) WILL RESULT IN SUCH PRIZE WINNER’S DISQUALIFICATION AS A PRIZE WINNER OF THE SWEEPSTAKES AND ALL PRIVILEGES AS A PRIZE WINNER WILL BE IMMEDIATELY TERMINATED.

The Sponsor assumes no responsibility for incorrect or inaccurate entry information whether caused by any of the equipment or programming associated with or utilized in this Sweepstakes or by any human error which may occur in the processing of the entries in this Sweepstakes. The Sponsor is not responsible for any problems or technical malfunction of any telephone network or lines, computer online systems, servers, or providers, computer equipment, software, failure of any email or players on account of technical problems or traffic congestion on the Internet or at any Web site, or any combination thereof, including, without limitation, any injury or damage to participant’s or any other person’s computer related to or resulting from participation or downloading any materials in this Sweepstakes. The Sponsor is not responsible for any typographical or other error in the printing of the offer, administration of the Sweepstakes, or in the announcement of the Prizes and Prize Winners. If, for any reason, the Sweepstakes is not capable of running as planned, including, without limitation, infection by computer virus, bugs, tampering, unauthorized intervention, fraud, technical failures, or any other causes beyond the control of the Sponsor which corrupt or affect the administration, security, fairness, integrity or proper conduct of this Sweepstakes, the Sponsor reserves the right in their sole discretion to cancel, terminate, modify or suspend the Sweepstakes. Should the Sweepstakes be terminated prior to the stated expiration date, notice will be posted on the Sponsor’s Web site and the Prizes may be awarded to winners to be selected from among all Eligible Entries received up until and/or after (if applicable) the time of modification, cancellation or termination or in a manner that is fair and equitable as determined by the Sponsor. All interpretations of these Official Rules and decisions by the Sponsor are final. No software-generated, robotic, programmed, script, macro or other automated online or text message entries are permitted and will result in disqualification of all such entries. The Sponsor reserves the right in its sole discretion to disqualify any individual they find to have tampered with the entry process or the operation of this Sweepstakes; to be acting in violation of these Official Rules; or to be acting in an unsportsmanlike or disruptive manner, or with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass any other person or to have provided inaccurate information on any legal documents submitted in connection with this Sweepstakes. CAUTION: ANY ATTEMPT BY ANY INDIVIDUAL TO DELIBERATELY DAMAGE ANY WEBSITE OR UNDERMINE THE LEGITIMATE OPERATION OF THE SWEEPSTAKES IS A VIOLATION OF CRIMINAL AND CIVIL LAWS AND SHOULD SUCH AN ATTEMPT BE MADE, SPONSOR RESERVES THE RIGHT TO SEEK DAMAGES FROM ANY SUCH INDIVIDUAL TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMITTED BY LAW. Entrants agree to indemnify and hold harmless the Sponsor from any and all liability resulting or arising from the Sweepstakes, to release all rights to bring any claim, action or proceeding against the Sponsor.

8. Privacy Policy: Bioneers and giveaway partners may collect personal data about participants when they enter the sweepstakes/when a winner is selected. Personal data may include: Name, email, address, home and office phone numbers and other supplied demographics-related information. All entrants will be automatically added to the Bioneers email list. They may opt out of emails at any time.

9. SPONSOR: THE SWEEPSTAKES IS SPONSORED BY BIONEERS/COLLECTIVE HERITAGE INSTITUTE, 215 LINCOLN AVE #202, SANTA FE, NM 87501.