The following is a transcript of Bioneers Co-Founder Kenny Ausubel’s keynote at Bioneers 2024.

In 2018, the satirical magazine, the Onion, ran this classic headline:

“Exxon CEO Depressed After Realizing Earth Could End Before They Finish Extracting All the Oil.”

Fast forward to 2024. Following Exxon’s record profits and the hottest year in human history, Exxon’s CEO blamed society for failing to produce solutions to global boiling caused by fossil fuels. He announced that clean energy doesn’t provide “the ability to generate above-average returns for investors.” So Exxon – and in turn the entire industry – are doubling down on fossil fuels.

Here on this 35th anniversary of Bioneers, it reminds me of a popular bumper sticker circulating in the early ‘90s: “It’s the corporations, stupid.”

Today we gather in a traumatic moment of existential dread. We harbor deep wounds amid radical uncertainty. Earth is a hot mess. In 2023, climate disruption brought worldwide ecological mayhem and the hottest year in at least 125,000 years.

At the Tehran airport in Iran last summer, the heat index reached 152 degrees Fahrenheit, beyond the limits of human survival and infrastructure.

In the US, we’re one election cycle away from Fascist rule. Authoritarian movements and dictatorships stalk the world while democracies falter.

We’re bedeviled by war and divisions at the very moment we must unite to address the climate emergency and the most extreme inequality in history. It’s no coincidence that corporations rule the world. As Paul Hawken said, “The more corporations are in control, the more the world is out of control.”

The arc of the moral universe is facing off against a straight-up hostile takeover. As the Fascist progenitor Mussolini observed, “Fascism should more appropriately be called corporatism, because it is a merger of corporations and the state.”

As the irresistible forces of nature and justice collide with the immovable object of concentrated wealth, we’re witnessing a pathology that psychologists call “extinction bursts.”

When a positive reinforcement is removed from a habitual negative behavior, it often provokes a backlash. Like a child’s tantrum, there’s a sudden radical spike in the intensity and frequency of the behavior, before it finally dies down and out.

Here are some snapshots of the countervailing forces at odds in this age of extinction bursts.

The fossil fuel extinction burst marks a desperate endgame to halt the unstoppable transition to renewable energy. In 2023, for the first time, investment in wind and solar outpaced oil and gas investments. No new investments in oil and gas are necessary. As Carbon Tracker reports: “A vast new energy system is emerging at scale that can challenge fossil fuels on multiple fronts. We’re entering an age of energy surplus and stranded assets.”

Hence the fierce market manipulations and savage attacks against disinvestment by “woke capitalism” and funds using Environmental, Social and Governance criteria. These ESG funds now comprise 14% of global assets and they’re plenty profitable without oil, gas and other destructive investments.

Meanwhile China has methodically positioned itself to dominate the burgeoning solar growth industry. It’s teeing up a market-making global juggernaut to deliver solar panels, electric cars and lithium batteries everywhere all at once – cheap. Buckle up.

Simultaneously, the wealth inequality extinction burst is reaching peak greed. The preposterous concentration of wealth is driving surging labor movements and widespread popular anger – both left and right.

Here’s why. With a combined wealth of $2.3 trillion, the Forbes 400 now own more wealth than the so-called “bottom” 61% of the country combined.

In 2023, for the first time, billionaires accumulated more wealth through inheritance than entrepreneurship, creating unprecedented dynastic loot.

Pro Publica compared how much the 25 richest Americans paid in taxes compared to how much Forbes estimated their wealth grew over 15 years. Their true tax rate averaged 3.4%. That matches the 3.3 percent average rate paid by the bottom half of taxpayers.

The result of the wealthy gaming the tax system is that federal budgets are starved – except of course for swollen military and intelligence budgets. Infrastructure is collapsing, social services have shriveled, and the solvency of Social Security and Medicare is chronically insecure.

Before the Citizens United decision opened the floodgates of corporate money and made free speech prohibitively expensive, the spending on the 2008 election was $717M. In 2020 it topped $14 billion.

So it’s no surprise that Princeton Scholars Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page found that “economic elites frequently get everything they want” while the odds of average Americans’ political desires becoming policy amount to “random noise.”

In these skid marks of plutocracy gone off road, labor activity has gained traction. Although union membership is at a historic low after decades of corporate assaults, the number of striking workers is at the highest in decades. Public support for unions is at its highest level since 1965: 70% of the general population and 88% of millennials.

The historic United Auto Workers strike has won not only major financial gains, but an unprecedented say in management decisions such as technology and investment. The UAW is now mobilizing to organize several more car companies and hundreds of thousands of non-union workers.

The Screen Actors Guild and Writers Guild shut down Hollywood and gained similarly unprecedented concessions. UAW President Shawn Fain publicly supported the strikes, saying: “Our fight is the same. The UAW has got your back.” This is new.

Most of LA was also on strike for months last summer, including hotel and public-school workers. Hundreds of retail stores have organized over the past few years, including Starbucks and Amazon. Recently, Starbucks unexpectedly caved and agreed to bargain for a national labor contract.

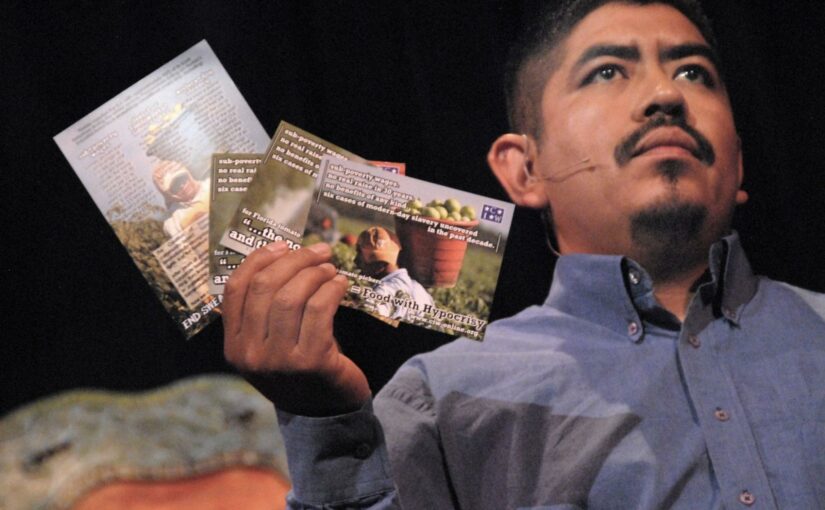

Some of the nation’s largest unions are on the move, from the AFL-CIO to the Teamsters and SEIU. One Fair Wage is helping organize hundreds of thousands of service workers.

Said UAW President Shawn Fain, “If we’re going to take on the billionaire class and rebuild the economy so that it starts to work for the benefit of the many and not the few, then it’s important that we not only strike, but that we strike together. Strikes work. Solidarity works.” Fain is now calling for a national general strike in 2028.

Meanwhile the Community Wealth Building movement is also gaining traction globally. It’s working to re-localize and de-corporatize regional economies, while democratizing ownership and decision-making.

Although it’s still the beginning of the beginning, we’re in a potentially transformative moment. Solidarity works.

Meanwhile, the monopoly extinction burst is meeting its match. For the first time since the ‘80s when Reagan killed anti-trust action, the Biden administration has revived two-fisted trust-busting. Here’s why and how.

Overall, about three to five giant corporations control around 80% of almost every industry and marketplace.

The largest corporations smashed their profit records in 2023, scoring a whopping 52% jump over already rising profit margins since 2018.

About 60% of skyrocketing inflation since the pandemic can be attributed to “greedflation.” Bot-driven pricing software now determines “what the market will bear.” It enables unified control of industry pricing into one centralized cartel. This kind of collusion appears to be systemic across the economy.

Monopolies raise costs, lower quality, depress wages, and stifle innovation. They destroy small businesses and bleed Main Street and marginalized communities. They’re antithetical to democracy.

Two-thirds of Americans now support antitrust laws and increased penalties. A large majority, both left and right, hold plummeting negative views of big business at large.

In response, in tandem with the Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission under Lina Khan has challenged over 40 mega-corporate mergers. As a result, about half have been abandoned entirely.

The FTC case against Google became the first major monopoly action in 25 years, with the epic Amazon and Apple cases close behind.

The rap sheet of industries facing anti-trust prosecutions grows weekly. Meanwhile, the FCC is moving to reinstate net neutrality, a huge potential win for the public interest.

In the EU, the Digital Markets Act has now taken game-changing anti-trust actions against Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and ByteDance, owner of TikTok. It provides a template for the US to rein in and break up Big Tech. According to polls, about half of Americans want to do just that.

The patriarchy extinction burst has radically escalated its war on women, climaxing with the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision overturning Roe v Wade. To justify the ruling, Justice Samuel Alito cited “eminent common-law authorities” including Sir Matthew Hale, the 17th century Lord Chief Justice of England.

In a time when, by law, women were considered property, not persons, Hale made marital rape acceptable under common law, and it remained legal in many US states through the ‘90s. Hale later presided over a trial of two women accused of being witches, which he firmly believed in. They were convicted and hanged. The trial became the model for the Salem Witch Trials in 1692.

In other words, the Dobbs decision was a modern witch hunt. It echoed back across centuries of misogyny, violence against women, and the denial of personhood and bodily autonomy.

The retrograde Dobbs decision is so far out of step with the popular will that it has mobilized voters to pass initiatives guaranteeing the right to abortion even in ruby red states such as Kentucky, Kansas, West Virginia and Ohio. It’s on the ballot in numerous states, and could well be a decisive factor in the 2024 elections.

The extinction burst against Black people and communities comes in the wake of the election of the nation’s first Black president and the Movement for Black Lives becoming the biggest social movement in American history.

Hence, the aging, white Republican Party has tripled down to restrict voting rights and to ban affirmative action, DEI programs, and the teaching of Black history and Critical Race Theory.

These are the desperate efforts of racial capitalism, as Thom Hartmann puts it, to “freeze what’s left of America’s racial hierarchy.” It’s Confederacy 2.0 – the Lost Cause born again to sustain both the racial and class hierarchy. It’s a last-ditch play to stem the inevitable tide of a diversifying electorate and a majority-minority population.

At the same time, a Christian Nationalism extinction burst coincides with white Christians dropping below half the US population for the first time. As Indigenous scholars have long documented, the Christian Nationalism resurgence we see today traces back to papal edicts climaxing in 1493 during Columbus’s triumphant return to Spain. The papal Doctrine of Discovery declared Western Christianity and European civilization superior to all other cultures, races, and religions. It was a theological license to conquer and kill.

The Doctrine blessed the Christian domination, colonization and enslavement of Indigenous peoples. It sanctioned blood-soaked centuries of land theft, genocide, and imperial extraction. It would soon escalate with the atrocity of the African slave trade. It laid the foundations of white supremacy as well as US property law. The Supreme Court has cited it in decisions from 1823 right up to 2020.

As the radical Christian historian Robert C. Jones writes in his book “The Hidden Roots of White Supremacy,” “The Doctrine of Discovery furnished the foundational lie that America was ‘discovered’ and enshrined the noble innocence of ‘pioneers.’ This sense of divine entitlement has shaped the worldview of most white Americans.” In other words, it’s the original Big Lie.

As Jones points out, a 2023 Christian Nationalism survey found that among white Americans today, this belief “is strongly linked to structural racism, anti-immigrant sentiment, antisemitism, anti-LGBTQ sentiment, support for patriarchal gender roles, and even support for political violence.”

A bitter irony is that Britain’s first export to its new colonial corporations was its own teeming hordes of the poor and dispossessed. Despised at home as “waste people,” they often came as indentured servants to be worked to death. The empire transformed these expendables into economic assets and frontier shock troops. They would become a permanent underclass and political pawn in the great game of divide, conquer and profit.

As then Texas Congressman Lyndon Baines Johnson would later put it: “If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”

So make no mistake – behind the curtain, it’s all one big package deal – a masterpiece of misdirection designed to obscure class war with identity politics, culture wars, holy wars, and blaming government as the problem.

Starting in 1971, Neoliberal corporate globalization began a full-frontal assault on democracy to embed minority rule by the rich once and for all. It aimed to undo FDR’s New Deal reforms and LBJ’s Great Society and War on Poverty programs. It sought to roll back popular environmental and consumer protections, as well as the cultural and political revolutions of the ‘60s. It set out to methodically capture the law, the courts, government, and the media.

It has been both a catastrophic success and an epic fail. It turns out that unlimited growth on a finite planet of have-nots and have-a-lots is a really bad idea.

As Jim Hightower likes to say, “The water won’t clear up till you get the hogs out of the creek.”

At the legal heart of the corporate coup is the doctrine of corporate constitutional rights. Manufactured by Supreme Court justices in 1886, the doctrine built an edifice on the text of the U.S. Constitution that afforded its highest legal protections to property and commerce. The 2010 Citizens United decision was built on the same scaffolding. It supercharged a bidding war for the best government corporations could buy.

In fact, before 1886, it was illegal in most states for corporations to spend money to influence elections, to prevent regulation of their own industries, and to write or block legislation.

In the early 1990s, the late Richard Grossman launched a revelatory historical inquiry into how corporations systematically came to occupy the law and override democracy through fabricated constitutional protections.

Richard asked this at Bioneers in 1996:

“Who’s in charge? That’s the question. Are we going to just ask corporations to be nice? Or are we going to instruct them how they’re going to exist?”

We used to instruct them, as Richard laid out:

- Corporate charters were issued for a set number of years – by legislatures – and after expiration, the corporation had to prove it was serving a public purpose to get another charter;

- Corporations were prohibited from owning other corporations;

- Boards and managers were individually liable for debts and harms caused by the corporation; and

- States could revoke corporate charters when corporations broke the law – a corporate “death penalty.”

By the way, most of these provisions were the law of the land in most of the states up to 1920. Until 1972 in Wisconsin, it was a felony for a corporation to make a political contribution. Perhaps it’s time to bring back corporate capital punishment for crimes of capital.

In many ways, since the beginning, the American story has been Democracy versus Plutocracy. Now we find ourselves teetering at the precipice where it’s Plutocracy versus a livable planet.

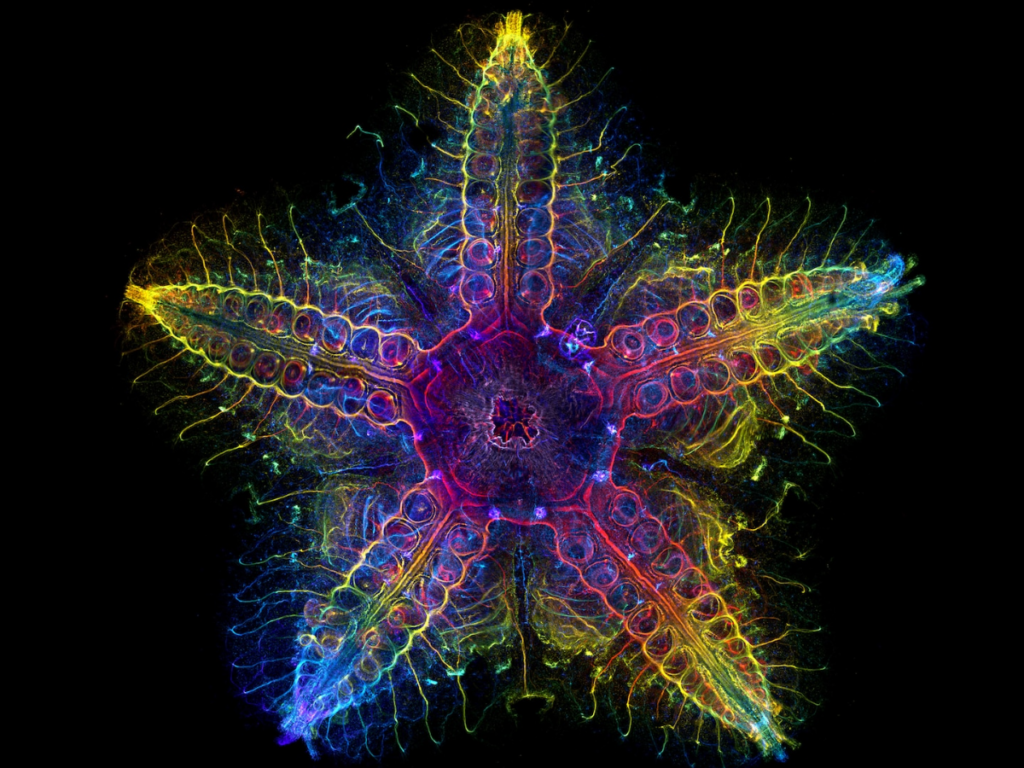

In addition to re-defining corporations themselves, we also need to create and enforce new human and environmental rights that, by their very existence, limit corporate rights. Those include recognizing community rights and the “rights of nature,” which is now the fastest growing environmental movement in human history, with Indigenous leadership at the forefront8.24. Nature is the missing personhood at the table, and it’s her table.

Indeed, democracy isn’t just on the ballot this fateful year. It’s on the chopping block. The forces of greed and nihilism are incredibly powerful, and Insurrection 2.0 is at the ready for a hostile takeover. But as Trumpelstiltskin rages into the abyss, arm-in-arm with the GOP – the Grand Old Plutocracy – it’s entirely possible it’s provoking an irresistible democracy burst.

It’s imperative that we build the power necessary to keep making the long-term transformational change that majorities of people want – and it’s also the world the world wants.

So how about in this age of extinctions, we extinguish corporate rule, and environmental destruction, and wealth inequality, and monopolies, and racism, and patriarchy, and misogyny, and the Doctrine of Discovery – and wars too.

So in closing, they say great stories cast a spell, but the greatest stories break the spell. To paraphrase Chief Rande Cook, Land Back leader of the Ma’amtagila people in British Columbia, “It’s time to stop stealing and start healing.”

As the spell breaks, one thing is for sure. To start the healing and stop the stealing, either we stand together or we fall apart. Our common ground literally begins with Mother Earth. Our many diverse movements are really one movement. Solidarity works.

As Astra Taylor and Leah Hunt-Hendrix so eloquently write: “Solidarity weaves us into a larger and more resilient ‘we’ through the precious and powerful sense that even though we are different, our lives and our fates are connected…

“Solidarity is the essential and too often missing ingredient of today’s most important political project: not just saving democracy, but creating an egalitarian, multiracial society that can guarantee each of us a dignified life.”

Thirty-five years ago, Bioneers called for a Declaration of Interdependence. Now is our time to realize it. May it be so.