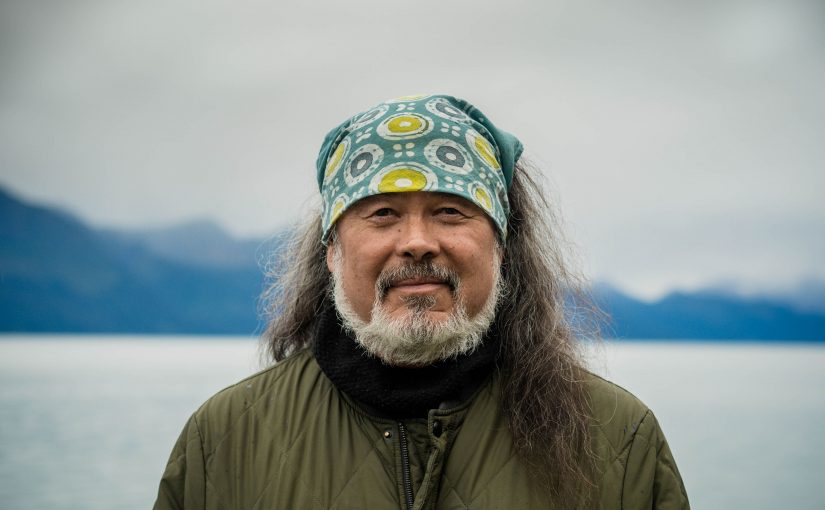

David Solnit is a San Francisco-based carpenter; climate justice, anti-war, arts, and direct-action organizer; an author; puppeteer, and trainer. He was a key organizer in the anti-WTO demonstrations in Seattle in 1999, and in San Francisco the day after Iraq was invaded in 2003. He co-founded Art and Revolution, which uses culture, art, giant puppets and theater in mass mobilizations, as well as for popular education and as an organizing tool. As an artist/activist (“artivist”), he has co-created visuals for the campaigns of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, National People’s Action and numerous other mobilizations and actions. David is also a direct action, strategy and cultural resistance trainer who currently works with Courage to Resist, supporting GI resistance to war and empire.

David edited Globalize Liberation: How to Uproot the System and Build a Better World and co-wrote (with Army veteran Aimee Allison) Army of None; How to Counter Military Recruitment, End War, and Build a Better World. He also co-wrote and co-edited (with his sister Rebecca Solnit), The Battle of the Story of the Battle of Seattle (AK Press 2009).

Bioneers’ Teo Grossman spoke with David about his history with artivism and how arts and storytelling can lead us toward a brighter future.

TEO GROSSMAN: Do you consider yourself an artist or an activist or both?

DAVID SOLNIT: I’m an artist, but I mostly call myself an arts organizer. Throughout public school and then in community college I loved making art – ceramics, painting, drawing — and I received some mentoring from one of the artists-in-residence we had in our high schools in Portland. I wanted to be an artist, but when I was 15 or 16, I became more acutely aware of the situation of the world: the threat of wars for oil loomed large at the time. President Carter had brought back draft registration, and all the kids in my high school who were surrounded by Vietnam vets and Vietnam era people who had tried to stop that war, feared being sent off to the Middle East in a war for oil.

So that got me involved in anti-war, social justice and environmental organizing, and at a certain point I realized that if I became a successful artist and made a painting that ended up behind some rich person’s couch, that wasn’t really going to help the world, so I shelved my professional art ambitions, and I’ve spent most of my adult life supporting myself doing carpentry and construction, but also funding myself so I could be a full-time volunteer organizer. I came up in the anti-nuclear direct-action movement, and we managed to stop the nuclear power industry, which was a huge, huge industry in this state, cold in its tracks in California by the end of the ‘70s.

TEO: You’ve become very well-known for your activist puppetry. I heard that one of your first big puppets was for an anti-nuclear weapons demonstration. How did that come to be?

DAVID: I got drawn into the anti-nuclear power and weapons movement, which really was in the tradition of the Civil Rights Movement of well-organized mass civil disobedience. I was inspired by that model and also very influenced by the feminist movement and the example of non-hierarchical organizations such as the Spanish anarchist “grupos de afinidade” structure. It was a really resilient form. People would stay organized even when 1,000 people were arrested and thrown in jail. They always had a plan and managed to overwhelm the authorities and often get demands met, so I was very drawn to that.

But at a certain point, I started to feel that we needed new ways of telling our stories, and one of my friends had just come back from the Heart of the Beast Puppet Theatre in Minneapolis. They do a giant May Day festival and, as part of it, make big puppets out of cardboard boxes, so I asked them to teach us how to make puppets for our next action. This was in 1989 at the Livermore nuclear weapons labs. I had spent five years organizing with Western Shoshone activists to stop nuclear bomb testing in the Nevada desert. We set up a workshop and K. Ruby trained me and many others in giant puppet-making, and we transformed that demonstration into a theatrical pageant. K Ruby and Amy Christian met there and went on to found Wise Fool Puppet Intervention, and we worked together quite a bit after that.

I took what I learned and started to recruit artists and performers. We were trying to use the arts to speak to people in a different way. That led to a project called Art & Revolution Collective, in which we cross-trained activists and artists all over the country, and that led to a series of actions culminating at the World Trade Organization mass demonstrations in Seattle in 1999, where we took everything we had learned those past few years, all the arts organizing we had been experimenting with, all the alliances we had built, and we deployed stilt walkers on butterflies and giant puppets to face the Darth Vader-looking police in the streets of Seattle, and it was a very effective part of the larger demonstrations by activists from all over the world, which turned out to be very successful at derailing the WTO’s meetings and its agenda and putting the anti-globalization movement on everyone’s radar.

TEO: You’ve been involved in direct action a really long time, from the late 70s to today, from the anti-nuclear movement to WTO protests to climate and social justice and Green New Deal and women’s rights campaigns and more. Have you seen like a shift over time in the way that the arts have been involved in these movements?

DAVID: Movements always use the arts, but I think there has been a kind of an emergent intelligence. A lot of people within the movements have started to realize that we need the language of art because the core conflict in our society is between dueling narratives, and if your opponents, the corporations and/or governments you’re combatting, hire top public relations firms and ad agencies and are able to be more powerful storytellers than you, they can keep wrecking the planet.

And that requires a shift, because secular rationalist activist types are used to making their case with facts, data and information but that alone doesn’t work. You have to explain that data and information through narratives that resonate in actual people’s lives, and that’s what the arts can do, if you use them right.

TEO: How does that express itself through the actual work that you do?

DAVID: Here’s an example: In 1999, when activists started to talk about corporate globalization, it sounded like a very complicated economic lecture in a college, so we tried to break it down using theatre and song and simplifying the narrative to convey the core truth in a way most people could grasp. We also had people tell their own stories: a sweatshop worker from Saipan traveled with us and told her own story embedded into the theatre piece, as did a locked-out steelworker from Kaiser Aluminum. They told their personal stories about the impacts of globalization on their lives as part of the performances in a way that people could understand and relate to emotionally as well as intellectually.

TEO: Do you think the climate movement has been able to make that sort of shift?

DAVID: There are really many climate movements. Everybody who’s impacted and fighting back, which is almost everybody, is part of it on some level, but I think the Climate Justice Movement is currently one of the most artful movements in the world. Many of us have pushed hard to lift it up. The People’s Climate March in New York City in 2016 was a good turning point where we were able to center the arts. The big coalition around that event provided the resources for two giant art spaces and getting stipends for some artists and artist organizers, and centering it in the march. Environmental justice communities from the greater New York area led by Uprose in Brooklyn, led the march and were holding giant sunflowers, a whole field of them that they had made themselves, each with a different message on it. And each section of the march had 16-foot banners on bamboo poles and giant parachutes. There was just a lot of art.

A ton of artists and metal workers and immigrant gardeners and all kinds of folks came and made parade floats, spending a month on them. It was a very artful march, and that model has caught on, and we’re not just talking about visual art, but music, song, theatre, performance, poetry, all that. And you’re seeing more of this sort of approach, be it in climate actions, teachers’ strikes, the Poor Peoples Campaign, etc. It’s important to get many people’s hands in planning and making this type of art. You want for it to become a space where all kinds of people come together and create together. We humans have always made things with our hands, whether it’s food, shelter or art, and it’s becoming a core part of our movements.

TEO: I know it’s a bit like asking which of your kids is your favorite, but are there particular banners or puppets or theatrical presentations that you were involved in that really stand out to you?

DAVID: After the Seattle WTO shut down, I met a group of farm workers from Florida, the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, and they asked if I would come to Florida to make art with their farm workers in preparation for a national tour to raise awareness about their struggle. This was the first time someone had said they wanted to prioritize making activist art three months in advance of their campaign, not the usual last-minute “Can you bring the puppet to the action tomorrow?” sort of thing.

So, I went to Florida and sat down with the farm workers and they talked about their work and living conditions, and we sort of collaboratively devised what became, to this day, the core image on their picket-signs, the giant plastic buckets they picked the tomatoes in. At that time, those workers probably had the worst working conditions of any low-wage workers in North America, in some cases actual something close to modern-day slavery, but they had been inspired by examples from Haitian, Mexican and Guatemalan peasant movements because some of their members had migrated from those three countries. In those places workers’ movements often used art and theatre in their organizing, so they were interested in doing that as well.

We made giant tomatoes and other props, and they would often do a silent theatre piece about their working conditions. I’ve been going there for almost 20 years now, and I’ve watched them use art and theatre together with smart strategic organizing with great success. They’ve turned the work conditions upside down, leveraging fair food contracts with the big buyers, so that if their human rights aren’t respected, they can actually stop the purchase of the product from the growers. The members of that coalition are probably now some of the more dignified low-wage workers in North America.

But it was a long struggle and many farm workers are still treated brutally. At one point maybe ten years ago a major case of modern-day slavery drew a lot of attention. Some farm workers had been routinely locked in a box truck each night, unable to leave, and not paid. The Coalition was pressuring the then governor of Florida to speak out about it, but he wouldn’t return their calls, so they called me up and said: “David, we’re going to go to the state capital. Can you make a giant box truck for a silent play re-enacting the events?” I showed up in Tallahassee, and we built a life-size box truck that included the shackles that chained the workers each night, and we had a cardboard sun for the day and a cardboard moon, and cardboard tomato plants where they were forced to work. Every TV station in the state showed it, and the newspapers wrote about it, and it made quite an impact. The governor called them back the next day…

TEO: That’s an incredible story. And you still work with them?

DAVID: Yeah. I’ve learned so much about organizing and centering arts and culture from them.

TEO: And I know that you’ve also been involved in the Standing Rock water protector movement. How did that involvement emerge?

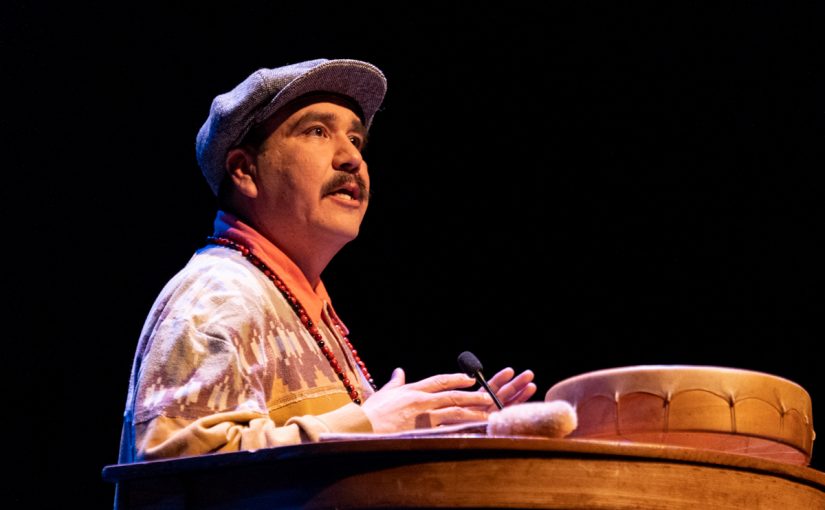

DAVID: I met Clayton Thomas-Muller through work in the Climate Justice Movement. He’s based in Winnipeg, and he’s a leader in both First Nations’ sovereignty movements in Canada and in climate justice campaigns throughout North America. And he asked me to come up and help make some art for a totem pole journey designed to travel and support different Indigenous struggles along the way that was ending in Winnipeg.

Clayton admired the work of Isaac Murdoch, a well-known Anishinaabe artist, so we ended up screen-printing one of Murdoch’s designs, the Thunderbird, (the spirit in the sky when there’s a lightning storm). We made giant 16-foot puppets of them, marched with thousands of folks, mostly Indigenous but lots of allies and people from all over, through Winnipeg. A few days later, they permanently installed the totem pole directly in the path of a pipeline that was being opposed in that treaty territory.

Winona LaDuke was in Winnipeg for that march, and when it was over, she took a truckload of the art to Standing Rock, and the youth who initiated that campaign were doing a run, and they carried the thunderbirds, and they really caught on there. So, through Clayton and through the Indigenous Peoples Power Project that was at Standing Rock doing trainings, I went to support the struggle. I brought a truck full of paint and plywood, and we set up and mass produced the thunderbirds there. It became one of the iconic images of Standing Rock and of the climate justice movement across North America.

TEO: Are there other iconic images from campaigns that had that kind of impact?

DAVID: Well, the giant sunflowers that led the People’s Climate March that I mentioned earlier have an interesting origin story. It began in Detroit during the U.S. Social Forum, part of the World Social Forum. The Global Anti-Incinerator Alliance introduced us to the Zero Waste Coalition in Detroit who were campaigning against a super toxic trash incinerator, and I agreed to make art for a march against that facility with my collaborator, Mona Caron, a San Francisco muralist.

I think they were the ones who suggested sunflowers as a possible image, because sunflowers can take toxins out of the soil and they provide nourishment and are a symbol of beauty and resilience, so we made a couple hundred sunflowers in someone’s front yard in Detroit, including a giant one so big (16 feet tall and 8 feet across) it had to be on wheels. And we made a giant mock incinerator, and we paraded through the streets.

Then, the sunflowers re-emerged as a theme in 2012. I live in California in the East Bay, and we have four major oil refineries there, mostly in Richmond, and in 2012 there was a massive explosion at one of those facilities that released huge amounts of toxic gases. 15,000 local residents had to go to a hospital with respiratory and other problems as a result. On the one-year anniversary of that catastrophe we did a mass march on that Chevron refinery, and one of the folks in Urban Tilth, Richmond’s Urban Food Co-op, asked what we would do we do when we got there, and a young farmer suggested we should plant some sunflowers because they bioremediate.

We got 1500 actual giant sunflowers from farmers in the region and used the images of sunflowers as well. 3,000 people came and marched on the one-year anniversary of the Chevron disaster at the Richmond refinery, and half of them were holding four-foot-high giant sunflowers marching through this industrial wasteland. Then, when we got there, we shut down the streets, and a group of artists, including Mona and Melanie Cervantes and Jesus Peraza and community members, sketched out and painted a 40-foot sunflower directly in the path of the main entrance to the Chevron refinery, so the sunflower sort of organically became a symbol of the Climate Justice Movement.

TEO: I’ve heard that some of this art and these ideas have spread all around the world. What it’s been like for you to see these things take hold globally, and conversely which current international movements inspire you?

DAVID: When I started working outside areas I could visit in person, I started to try and figure out how to make resources that people could use all over. We tried to create images that could speak beyond language, so some of the images we’ve used have indeed been widely picked up. We’ve also directly worked with artists from all over the world. We did a Rise for Climate Action in which we had one artist from each continent create an image, each one using as a starting point an orange X which symbolized “stop destroying the planet” and a yellow sun which suggested a desirable alternative. Christi Belcourt, an amazing Métis First Nation artist, did a beautiful one, and artists from Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Pacific Islands, all contributed, and some of those images are still widely used.

TEO: Another thing I wanted to ask you about is mentorship and apprenticeship. I know you care a lot about passing what awareness and understanding you’ve gathered over the years to new generations. Can you share a little bit about how you approach teaching others the unique skillset you’ve developed at the intersection of all these movements?

DAVID: On the basic level there are some physical handcraft skills that you need to make physical objects and a different set of skills if you’re doing theatre or singing, and we need all of them, and they can be learned, but shifting the culture of movements is more complicated. I worked with 350.org for five years, and I was the sole arts organizer out of 150 or 200 of their organizers on planet Earth. And for them to have an arts organizer on staff was an anomaly. Most organizations think of art as an afterthought and invite artists to contribute something to an action or campaign at the last minute.

Many of us in the activist art world would like to flip that upside down because we think effective, engaging storytelling is critical to getting our points across. Of course, we need administrators and policy experts, but not necessarily as the main or only communicators of a movement to the broad public. So, yeah, I and other arts organizers engage in a lot of skill sharing and trainings, live and online, and we try to get resources to both artists and organizers who include art in their work. In the last giant project I did, for Defund Climate Chaos, which targeted banks financing the fossil fuel industry, we produced 30,000 posters with six movement artists that were printed on cheap newspaper and shipped out. People assemble them and then wheat-paste them on appropriate sites in their communities, and that project also served as a skill-training, so now some 600 more groups of activists know how to do street wheat pasting.

But the skills we need to teach are not just about actual art-making. To be successful in this space, you need a wide range of skills. You need to know how to facilitate a meeting, host a press conference, write a press release, give a talk, explain an issue, lead a song, put together a short play or skit, etc., as well as organize an art-build to make the physical art.

TEO: You’ve been part of these social movements for so long. On the one hand this is a very depressing time, but it also seems to be a really dynamic time for all these intersectional social movements, and activist art seems to be flourishing. How are you feeling about it all at this point?

DAVID: One thing I like about making art with other people is it is that it’s enjoyable, and it gives people an opportunity to celebrate. If we can create a little bit of what we want the world to be like even as we’re opposing the bad stuff (of which there’s a lot). There’s no denying that this is a really polarized, challenging and dangerous time and that we need to desperately change the shape of our society, and fast. But I think that if we’re smart, strategic, and learn to be better storytellers than those who seek to divide and keep us down, then we can actually win a lot of changes, as we did in the ‘60s and ‘70s. And I think centering arts even more will help us win. I mean, for the sake of human survival, we have to win. We have a tight timeline, and we have to win majority support, and arts and storytelling can be the way to do that.