This keynote talk was given at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

Given the existential threats of climate change, economic inequality and ever escalating political instability, we need concrete, integrated solutions to our shared problems. An inspiring model of what such an integrated approach could look like is Jackson, Mississippi’s Cooperation Jackson, an emerging network of worker cooperatives and solidarity economy institutions working to institute a Just Transition Plan to develop a regenerative economy and participatory democracy in that city. brandon king, Founding Member of Cooperation Jackson, shares his experiences helping conceive and build these extraordinarily promising strategies and social structures that reveal that we can put our shoulders to the wheel and build a truly just and sustainable future.

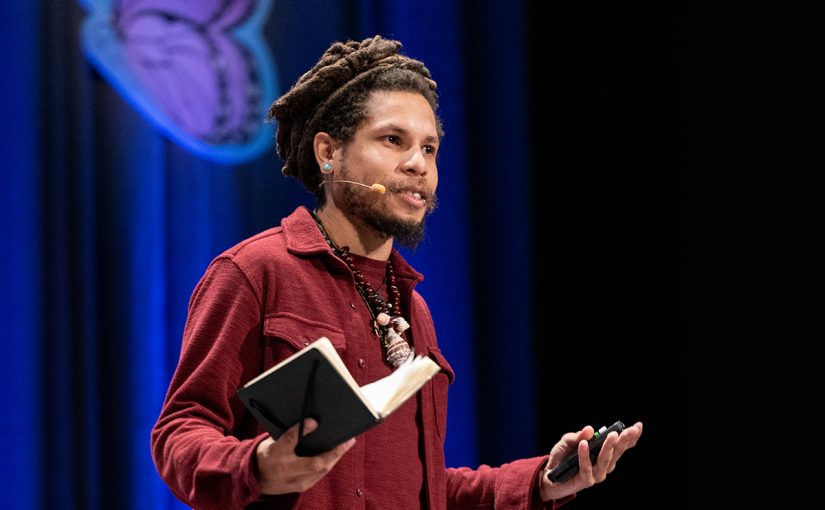

brandon king is an community organizer and cultural worker originally from Hampton Roads VA, currently living in Jackson MS. After graduating from Hampton University in 2006 with a BA in Sociology, brandon moved to New York City where he worked as a union organizer and later as an organizer working with New York City homeless people.

To learn more about brandon king and his work, visit Cooperation Jackson.

Read the full verbatim transcript of this keynote talk below.

Transcript

Introduction by David Cobb, Cooperation Humboldt.

ANNOUNCER:

Please welcome the founder of Cooperation Humboldt, Mr. David Cobb. [APPLAUSE]

DAVID COBB:

Good morning, Bioneers. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] So I have the distinct privilege of standing before you to introduce brandon king, and so that’s the main reason I’m here.

But I’m also here for another reason. I suspect the reason that many of you are here. And that’s because I know that we are living in a moment of fundamental crisis, actually a series of crises, an ecological crisis. It’s not coming, it’s here and getting worse. It’s an economic crisis because we are living in late-stage capitalism and watching as this economic system continues to destroy the planet and create a racist, sexist, and class-oppressive world order as we go over the cliff. And that is leading to a political crisis because our current political institutions cannot solve the problem. How am I doing so far? [APPLAUSE]

Okay, so we’re in the right spot. And I want to be clear that what this means, these three series of crises are called systems collapse. Now, in one sense, that’s a good thing. It’s a good thing because our current systems are fundamentally premised on white supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy, and empire. So it’s goo that those systems are collapsing. In another sense, we recognize the sense of joyful urgency that this moment creates for us, because we are the generation that is going to have to shift the dominant institutions from the power over, dominating, extractive systems back to the ecologically sustainable and socially just systems that once existed. And that’s why I applaud the commitment that Bioneers is making, and more and more people are making, to go back to indigenous people who still know what that means. [APPLAUSE]

I study, relate, and work with indigenous people not to make myself feel good. I already feel good. [LAUGHTER] I study and relate with indigenous people because I want to live. And I know that they remember the ways to live properly so that my children and grandchildren can live too. [APPLAUSE]

So I’m here to introduce brandon king because brandon king is a founder of a group of people doing that work right here, right now, in the United States, the capital of empire, and doing it in a way to meet people’s material needs. Brandon king is a farmer. He is an artist and culture worker, and he’s a revolutionary. I know that because that’s what he told me the first time I met him several years ago at Cooperation Jackson when that experiment was first beginning. He was an inspiration to me then. He is more than an inspiration to me now because he has data about what this experiment looks like. He has lived experience about what it means to begin to make a just transition.

Brandon will tell us, I hope, about what he and his colleagues and comrades are learning in Jackson, Mississippi, the heart of the old confederacy, about what it means to create conditions to shift to a just transition, to meet people’s material needs in economic ways concretely, both the challenges—So I don’t expect to just get a uproarious everything is good. I hope we’ll get a little of that, but I hope he will share it with us, exactly what they have learned so we can begin to apply it.

Ladies and gentlemen, please help me in welcoming a DJ, a farmer, and a straight up revolutionary, brandon king. [APPLAUSE]

BRANDON KING:

Peace, Everybody. How’s everybody doing this morning? [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] I think David, he spoke well. I think he sort of—For me, I consider myself an aspiring revolutionary, because that’s a big, big, big, big word, and there’s people who really deserve to carry that. Right? That’s a big responsibility. And I hope upholding what my ancestors would like for me to do and would like for me to be.

So, yeah, I’m here to talk about just transition, like transitioning from an extractive, destructive, exploitative economy to one that affirms life, to an economy that is regenerative, to an economy that honors Mother Earth, honors the sacred. How can we sort of get back to those ways? And, yeah, I think about just transition, and I think it needs to be a framework which includes social justice, because many times the people who are on—who are mostly directly impacted by climate change are the communities on the frontlines, and so a social justice framework should be sort of put in place when thinking about a just transition.

So, I think right now, it’s a call for us to have a bold commitment to radical change, and to take action, and we need to go back to and—1) I think science is calling it out. They’re like, We don’t have a lot of time. And 2) I feel like there’s deep indigenous knowledge that has been telling us that we need to listen to in terms of shifting the way that things are currently, and going back to ways that were in alignment with the planet and in alignment with the Earth.

And so I want to share a bit just about Jackson, and about what’s happening locally, and this experiment, this project that I’ve been a part of and have been—like before it was even a name of an organization, I had been sort of working towards building something that is a self-determined, something that is life-affirming for black people in the US. And so this plan that we had is called the Jackson-Kush Plan. Jackson, Mississippi.

And what David talked about in terms of Jackson being a place that is the heart of the confederacy. All of that’s true. It also is a place where a lot of folks who migrated up North because of Jim Crow violence, because of white terror, the people who stayed are people who understand the need for self-defense and self-determination, and defending what’s theirs. There’s a rich history and culture of resilience that’s in Mississippi that I don’t think gets spoken much about.

But, yeah, so Jackson, we had this plan, right, and we wanted to develop people’s assemblies, so figure out ways to do people-centered decision-making processes. We wanted to pursue political office but to do it in a way where our politics are ours. It’s not beholden to the two-party system that’s in bed or in alignment with this capitalist sort of structure. Right?

And the other thing, which is the project that I’m a part of building, is building a solidarity economy. And so Cooperation Jackson comes out of an organization, a New African People’s organization, the Malcolm X. grassroots movement, which I’m—which I come out of. It’s the goal to build power for people.

And so, yeah, there’s different things that sort of play into that. Right? Jackson being a place that is in contention, contention with gentrification and communities that are looking to prey upon the existing community, and grassroots folks that are looking to shift power and shift control and shift wealth and resources to themselves and to the community. Right? So that’s what we’re sort of in the heart of.

When I think about Jackson and when I think about just transition and how it looks in the South is something where you can’t just build in a way without opposition in Mississippi. The laws—You can’t even officially incorporate as a cooperative in Mississippi. So the question of building and fighting, it wasn’t even a question around fighting because that’s already is. You know?

And so when we think about shifting and transforming the world around us, we want to build in a way where we’re building green worker cooperatives, where we’re doing community production. I don’t know how many people know about that. If you’ve heard of maker spaces or fab labs or 3D printing and stuff like that, I feel like we’re on the edge of being able to produce the means ourselves. I think the whole question around seizing the means of production is a real question, and that needs to be addressed. And we exist in a world and a time where we can start to produce the means ourselves with existing—with the resources existing in our community. [APPLAUSE]

And so that’s what we’re embarking upon just with Cooperation Jackson. We want to build an eco-village, like how can we incorporate a bunch of different practices from composting to using solar energy, to using—producing the homes from the materials that exist within our community, all of these different things to build a sustainable sort of infrastructure for our folks. Those are some of the things. I mean, because if you think about just transition, for me, I’m like capitalism in many ways takes our time. It takes our time. Right? Like most of the time we’re working all day and all night or whatever because we’ve got to pay bills because we’ve got to live in a house, we’ve got to pay for food, but like how about if we were able to set up a situation where we have housing, we’re growing food, that’s less reason for you to want money. You can have money to do other things that you like want to do, but if we take away the things that are—if we take away the things that—Actually if we provide the things that we actually need in order to survive, it makes us less dependent upon these systems that are harming us. [APPLAUSE]

And so in Jackson, we have this thing called the Sustainable Communities Initiative, and my thing is it’s like—it’s a local sort of project. The—Something’s may be transferable to your situation wherever you are, and I think a principle of just transition is that it’s local communities figuring out what local solutions work best for them. So with our research and with folks have been doing for 30+ years, this is what we came up with in terms of like how to address building a sustainable, regenerative community, and if you could see, thinking about alternative currency as something, building a community land trust, which is something that we have, eco village, all the things.

And so just wanted to show this graphic. One of the ways we’re—we sort of came about our work, it’s like we didn’t think about it doing it just like one thing, like we’re just going to do farming or we’re just going to do catering, or we’re just going to do arts and culture, or we’re just going to do composting. We were thinking about like whole systems approach. What are the things that we need in order to sustain life? How can we work in a way where we are owning our labor? How can we work in a way where we are learning collectively how to be democratic with each other?

I think this country in many ways talks about democracy, but we don’t know how to do it. We don’t know how to do it. [APPLAUSE] Because I mean it takes a deep level of patience and trust in each other that we’re going to come across or come to the decision, but there’s a struggle that happens when we’re actually listening to each other, when we’re valuing each other’s opinions. I feel like the exploitative, the extractive economy that values bosses, they would have get[?] things done a lot quicker because it’s just one person that decides, but when we’re making space for all of us to decide, the process is a bit slower.

But the challenge is that with climate change we don’t have much time. Right? And so how do we do these things? How do we hold ourselves? How do we hold each other? How do we learn how to be democratic with each other? How do we learn how to share resources and wealth, and distribute that with each other? All of those things are the things that we are experimenting with and trying in Jackson. [APPLAUSE]

I don’t know if y’all seen this map before, but this map is—Movement Generation put it together, folks in Our Power campaign, the Climate Justice Alliance, which Cooperation Jackson is a member, with just a layout of what the extractive economy is and what the values are of an extractive economy, and how can we—how we can move and build towards a regenerative economy, an economy that affirms life, that—the worldview is about caring, and protecting, and honoring the sacred, where the purpose is ecological and social well-being, where we’re building deep democracy. Right? Like I said, like the—being patient with each other, and knowing that it may take some time to come to decisions, but if we hold each other, then that’s all the more good for us. Right?

And so, yeah, the goal is to build a living economy, one that affirms life. [APPLAUSE] So we have a center. It’s called the Kuwasi Balagoon Center. Kuwasi Balagoon was a New African anarchist based in New York City, but he was a citizen of the Republic of New Africa, which is based in Mississippi. Jackson is a part of it, the land—and he was in the Black Panther party, was forced underground into the BLA, the Black Liberation Army. But the territory, when he was talking—fighting for sovereignty and self-determination, it was the South. It was Jackson.

And so when we think about someone who believed in horizontal decision making, who was also queer, who believed in being completely free, we look to this person. This person also said a lot about growing food in vacant lots. He said a lot about learning how to can food. He said a lot about staying in shape and working out together. He said a lot about free clothing exchanges. He said freely—like anarchist clothing exchanges. But all of these things I feel like are, for me, it’s like a monitor. It’s a monitor to a barometer to like where we need to go, and an inspiration of where we’ve been, and where we can go.

And so that picture right there is like a picture of him. I painted it, and I donated it to the center. And, yeah…[APPLAUSE] So, yeah, the background is about freedom. I just thought about complete freedom: What would that mean? How would that feel? And in the foreground that’s him. And the painting is a picture that he drew actually, that I redrew, but it was on his obituary. It’s called Piece By Piece, Fight by Flight. Yeah, so yeah, that’s that. [APPLAUSE] It’s cool to share my art work with like mad people. [LAUGHTER]

So yeah, so that’s the center. We also have solar like on our—on the Kuwasi Balagoon Center, but also on the community production space as well. I’m sorry it’s all pixelated.

And then, so Freedom Farms Coop is a coop that I’m an anchor for as well, and the goal for Freedom Farms is to grow food for our community to incorporate agroecology and Afro-ecology principles and practices, and figure out a way to build food security towards building for broader food sovereignty. So we’re growing food to feed people. [APPLAUSE]

And that’s—And, yeah, and so I mean, the goal, we’re going—we want to build to scale, but we also know that we—there’s a learning curve, and there’s also—I feel like history and ancestral history and trauma, all of those things are real in the black community, and it’s sort of difficult to get black folks to be back on the farm because of our history that we’ve had with the land here, and how we’ve interacted with the land here, based on our exploitation. And so there’s a deep level of healing from the trauma that has to happen. And folks—And we’re working on ways to figure out how to do that, and to be mindful, because we know that our history with the land came a long, long time before our enslavement, and we also know that because of the agricultural technologies that our communities had in West Africa, folks were directly targeted in order to implement that here on these lands. So, yeah…

So the Green Team, they do landscaping and composting, whatever. Trimmings that they get from the leaves or whatever from their jobs, we make that into compost. The compost goes back to the farm.

The Community Production Cooperative, like I told you, like I said before, it’s about—it’s about how can we create the means of production ourselves using tools that exist. So fab lab equipment, it’s like I think 30 or so different tools, like different robots kind of things. And if you put these tools together, you can make almost anything. And it sounds really weird until you like actually see it. [LAUGHTER] And I’ve seen it. I’ve been to fab labs. There’s one in Detroit that we’ve connected with, Inside Focus. There’s fab labs all over the world – Barcelona, in Chile, in Africa, all over.

And so, yeah, I think it’s important to—If there’s thing within our grasp that could help us to gain more control over our lives, like how can we do that, and how can we engage in that process. Right? And so one of our goals is to be—like to delink from the systems that are harming us, and delinking, I think, requires us to be—have some sort of sense of what the value chain and exchange chain sort of looks like, and how do we sort of gain control over those aspects. And to be able to demonetize that, and to do it in a way that we decide what the value is rather than the markets. [APPLAUSE]

So, yeah, so a goal of building a transition city, that’s what we’re about. The land that we have is on a community land trust, Fannie Lou Hamer. It takes the land and the housing off the market. You’re able to say land in a community land trust can’t be sold for over 99 years. And there’s a board that includes people from the community that decides what happens to that land. And so all of our land that we have from housing projects to our production spaces, all of that is in the community land trust. Yeah. [APPLAUSE]

And so, in closing—I’ve got like 30 seconds—one thing that I want to say is that urgent action is needed. I think—I was thinking about the workshop I went to in the indigenous tent about Alcatraz and Standing Rock, and just to think about how many indigenous territories were reclaimed after Alcatraz because of people being inspired to take action. [APPLAUSE] Those kind of things are very important for us to do and to think about.

I think in closing, there’s a resource gap for groups locally that are trying to do similar things. I think it’s important for us to figure out how to connect and to build solid relationships with each other. I know that the task is super daunting, and at the same time, I feel like we have the capacity, the potential, the wherewithal, and we also have our ancestors that are—that I feel like want us to live in a better and more just, more humane, more—world that is in right alignment and right relationship.

And, yeah, I’m looking forward to doing that, continuing to doing that with y’all. Yeah, peace. Peace. [APPLAUSE]