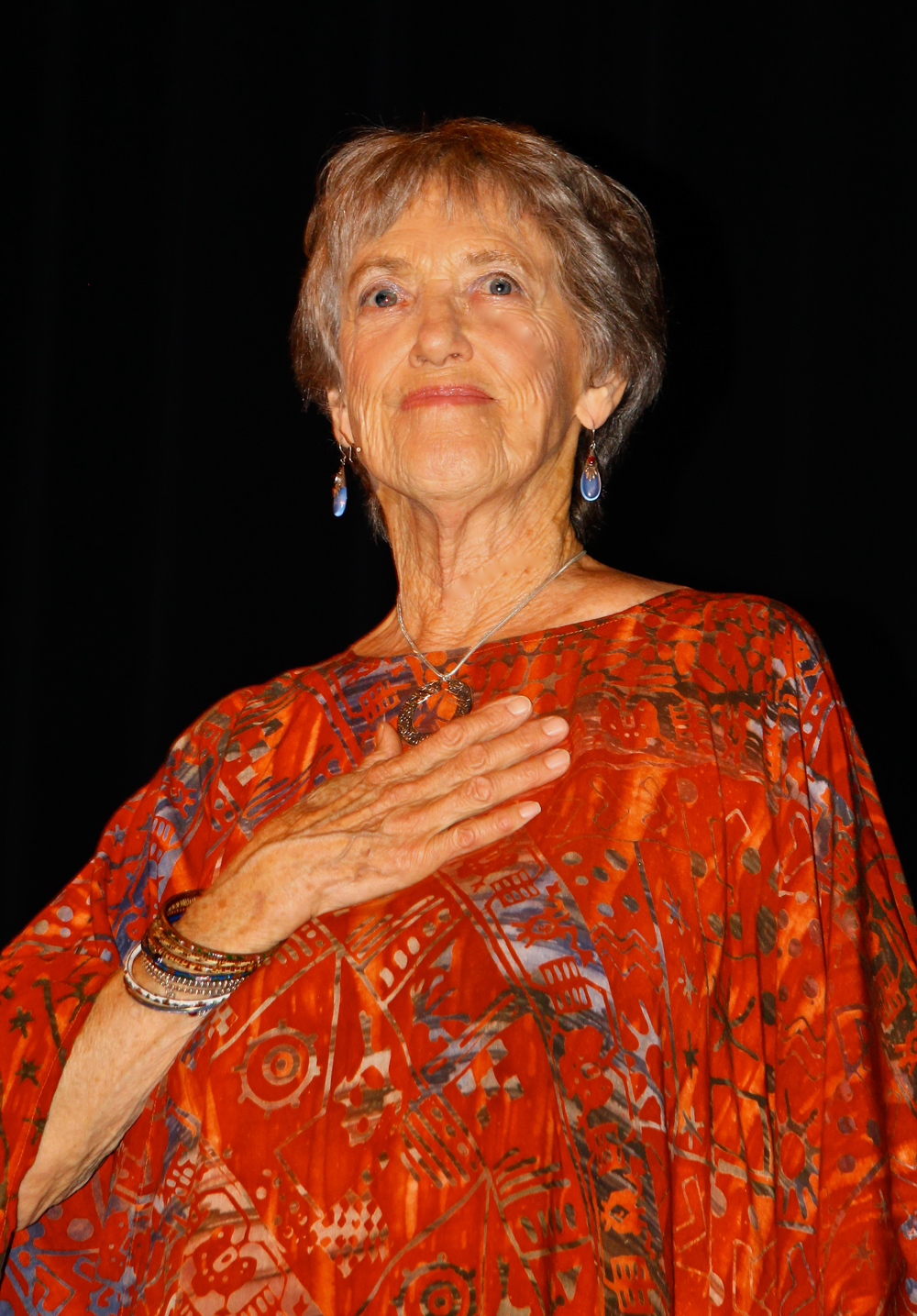

Water sustains our living world, but as environmental advocate, moral philosopher and award-winning author Kathleen Dean Moore writes, it can also be a dark and dangerous thing. In the following essay, Moore, Distinguished Philosophy Professor Emerita at Oregon State University, examines the impact of fracking on this precious element.

The essay, “When Water Becomes a Weapon: Fracking, Climate Change, and the Violation of Human Rights,” is an excerpt from volume three, “Water,” of the five-volume anthology series “Elementals.” From the Center for Humans & Nature, publisher of the award-winning anthology series “Kinship,” “Elementals” brings together essays, poetry, and stories that illuminate the dynamic relationships between people and place, human and nonhuman life, mind and the material world, and the living energies that make all life possible. Inspired by the four material elements, the “Elementals” series asks: What can the vital forces of Earth, Air, Water, and Fire teach us about being human in a more-than-human world?

As evening comes on, my friends and I look over rolling hills of wind-silvered grass and a stock pond beside a windmill, slowly turning. Silhouetted against a livid sunset, three pump jacks tilt up, tilt down, up and down, ceaselessly, metronomically, silently; we are too far away from the fracking fields to hear them thud and squeal. The stock pond turns pink as the sunset fades, and by the time we finally hike back to our car, the pond floats a silver ladder of moonlight. Long into the night, the water holds the light.

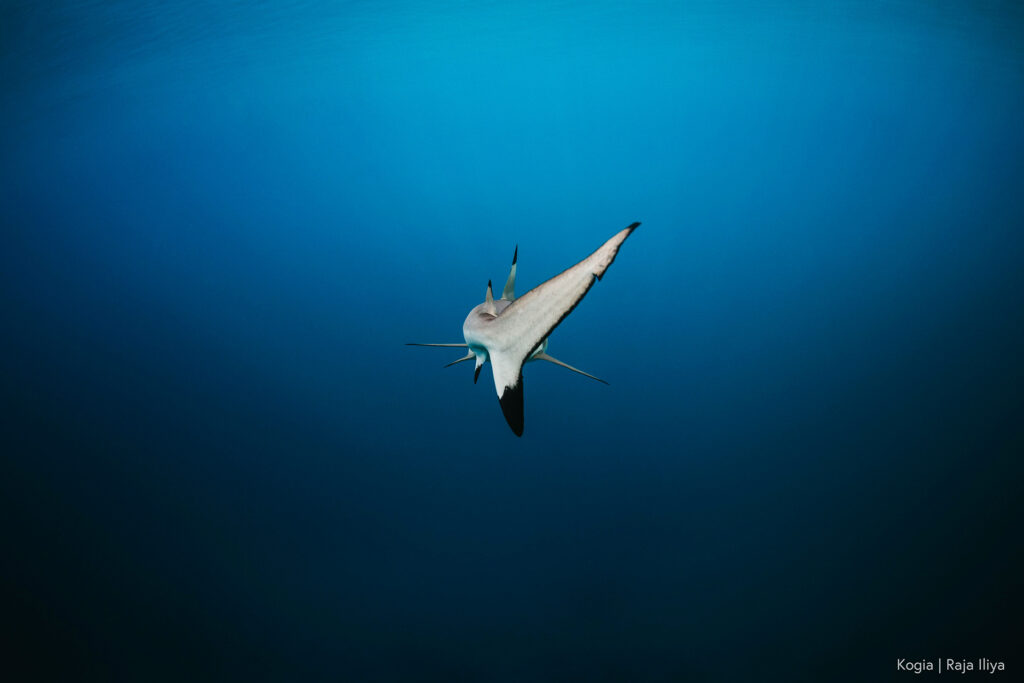

But water can hold darkness too, and that is the subject of this exploration—how water can be made into a dark and dangerous thing. This will take us on a journey into the blackness deep underground, where blind water seeps and shushes through sand and silt. Here, in this darkness, is where the industry of hydraulic fracturing is turning water, an element essential to all living things, into a weapon against life.

…

Imagine that we can make ourselves small enough to follow a root into a crack in the rock, and down, and down, between grains of sand and through porous rock. It’s dark down here—a prehistoric dark, a Pliocene dark, the dark of the past and of the future, the dark of dreams and crypts. Hard to say how far we have crept down through the tiny spaces. Fifty feet? Three hundred? But suddenly, water flows between every grain of sand. We have reached the top of the water table. Below us is an aquifer, water-soaked sand resting on an impermeable layer of clay.

On Earth, there is more fresh water down here in the silent rock than there is on the green and frenzied surface. In uncounted aquifers, fissures, underground rivers, and saturated sands, vast volumes of water silently, slowly move downhill under the pressure of gravity and the weight of tons of rock. Geologists call this groundwater “cryptic water” because it is mysterious and undeciphered.

This is what gives life to Earth—this water of light, this water of darkness—and the movement from one to the other through long space and time.

How can I describe the water? It is dull black, of course, so far from the light. Maybe it smells vaguely of life, because there is life down here, a complex biosphere of bacteria and other microorganisms—maybe a greater biomass of life underground than on the surface of the Earth. The water is cold. Or sometimes it’s hot. Maybe it tastes stale. I don’t know—the water might have been down here for ten million years, or longer even than that, at home in this black, shivering, watery world unknown to us.

Some of this water may be “dead”—that’s what the geologists call it when the water is imprisoned between impermeable layers, never to be part of the hydrological cycles. But most of the water is moving, flowing—if I can use that term for a process so slow— across a clay, maybe, or a glacial till, a giant sheet of water straining through sand, fracture systems, and fissures. Occasionally, water will find an opening and emerge from the darkness in a spring or a rancher’s well, an oasis, or even a river—in a sudden splash of light, tinkling, twinkling, released, free as a fish.

And then it will embark on the next stage of its hydrological cycle in a cottonwood swale, or in a bison’s flicking tail or the fly it flicks, in a quaking aspen leaf, in wild strawberries or spinal fluid, or in a glorious thunderhead blooming purple over the bison range. This is what gives life to Earth—this water of light, this water of darkness—and the movement from one to the other through long space and time. This is what creates the abundance of Earth, the singing of rivers and children, the paradise of plenty. This is how Earth grows beings who turn their faces to the night sky and sing praises. This is why Earth is not Mars.

…

A heavy drill with diamonds in its teeth grinds through the gravel and sandstone, down and down into the darkness, maybe a mile or more through dozens of geological layers and pockets of fresh water. Then it turns and drills horizontally, maybe another mile under the bison range. Who knows the sounds that vibrate so far underground or the smell of hot steel on sandstone? Who knows the sizzle when the bit touches water?

Roustabouts line the wellbore with concrete. Then into the wellbore, they pump fracking fluid or “slickwater” under pressure. Fracking fluid begins as fresh water. Oil companies draw the water from lakes and streams and often from the groundwater. How much water? It depends: somewhere between two and twenty million gallons of fresh water for each frack job.

Now slippery, gelatinous, and entirely poison, the fracking fluid is forced down the wellbore under tremendous pressure. Twelve thousand pounds per square inch? Nine thousand? Numbers vary, but approximately the pressure a hand would feel if it were crushed by a steamroller. The fluid hits an opening in the concrete liner, explodes out with enough force to crack rock into shards and open long fissures. Silica sand is sent down to prop open the caverns, and oil and gas ooze or gusher out, beginning their complex transformation into money.

In great slurry blenders, any of at least 1,021 chemicals can be mixed with the water to make the fracking fluid. It’s hard to say what they are exactly, because the industry conceals much of that information. Trade secrets. But here are some of the chemicals: Benzene. Toluene. Ethylbenzene. Xylene. Arsenic. Cadmium. Formaldehyde. Hydrochloric acid. 2-Butoxyethanol. Ammonium chloride. Mercury. Glutaraldehyde. Other secret poisons to kill the microorganisms in the rocks before they can gum up the drill. These are chemicals customarily used to kill insects, clean toilet bowls, strip paint, polish brass, etch glass, preserve corpses, and commit murder. At least 157 of the fracking chemicals are reproductive or developmental toxins, causing birth defects, breast and prostate cancer, miscarriage, and other heartbreaks. The health effects of an additional 781 chemicals used have not been studied.

As poisoned water becomes the explosive weapon that smashes rock, this process is called “hydraulic fracturing.” It might more properly be called “weaponizing water” against the very Earth.

Some of the poisoned water is forced through fissures in the rock, where it seeps into the underground aquifers, carrying radium that it absorbs from the rocks themselves. But between 18 percent and 80 percent of the used fracking fluid—what we used to call “water”—is brought to the surface. What happens to it then? Some of it is stored in open impoundments, which may or may not be lined to prevent seepage. Some of it is dumped into streams. Some of it is sprayed onto agricultural land. Some of it is evaporated from pits, the residue used to melt ice on highways.

But much of the fluid waste is injected back into the earth, where it finds its way along faults, through sands, eventually into the groundwater and some into well water, in an inevitable process called “migration,” as if the toxins were birds or wildebeests. There are more than 480,000 underground waste injection wells in the United States alone; 30,000 of them force fracking fluid thousands of feet through water-bearing layers underground. No one knows how many wells are leaking. No one knows how much toxin finds its way into babies and breasts, into forests and agricultural land, into rivers and so into rice, where water becomes again a weapon, an agent of darkness and death.

…

The Dakota Access Pipeline carries “sweet” crude oil from the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota to oil terminals in Patoka, Illinois. In its 1,172 miles, it crosses hundreds of streams and burrows under twenty-two bodies of water, including Lake Oahe, an impoundment of the Missouri River that provides drinking water to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. Fearful of the good chance that the pipelines would leak into water that sustains their people, the Sioux rallied to stop the pipeline. These are the famous Water Protectors of Standing Rock. Hundreds of people came to help them stand their ground. Setting up encampments along the planned route of the pipeline, the people moved to block the progress of the great machines. The pipeline company, Energy Transfer Partners, brought in private security officers, the governor called out the National Guard, and local law enforcement officers moved in to clear the protesters.

Imagine the Sacred Stone Camp on a frigid night in midwinter. Searchlights flash through darkness that echoes with cries of “Water, not oil,” “Water, not oil.” Tear gas and the smoke of concussion grenades sting the night air. On one side of the Cannonball River is a phalanx of armored vehicles and police in full riot gear. Facing them: a crowd of Water Protectors, some wearing raincoats, but others protected only by plastic garbage bags and goggles. As shouts and rubber bullets zing across the river, the officers bring out their most powerful weapon. Water.

With water cannons as fierce as fire hoses, law enforcement officers blast the Water Protectors, knocking the people off their feet, tearing their clothes, and drenching them in ice water. People scream and run, trying to protect their faces from the force of the cannons. “We are cold. We are shaking. We are wet. We are in pain,” one woman said, assaulted by the sacred element they were trying to protect—water turned into a weapon.

…

“Mni wichoni.” “El agua es vida.” In any language, water is life. But when water is made into death, we enter a sinister alternative moral universe where wrong is right, and profit is valued more highly than life itself. There is a breathtaking moral nastiness in wielding deliberately pressurized or poisoned water—naturally the source and sustainer of life—as a weapon against life. There was a time, and the time will come again, when this is morally unthinkable.

The wrongs begin as the oil corporation draws fresh water into its tanks. It is undeniably true that the life of every person on the planet depends on the 1 percent of Earth’s water that is fresh and available. Of this limited supply, the US fracking industry uses an average of 105 billion gallons each year—as much as the water use of three million citizens of Chicago. Worse, this water is often seized from water sources essential to local people and extracted from some of the most arid and water-starved places on the planet. Because no technology exists to return fracking waste to potable water, this water becomes removed, maybe forever, from the hydrological cycle—a dangerous waste of the rare and wonderful gift of water.

Move on to the slurry tanks, where the symbol of innocence and purity, that agent of cleansing and renewal, is laced with the seeds of death. No one knows how the poisoned water spreads through the lacework of rock formations or human veins. Thus, in the 2018 judgment of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal, a respected international opinion tribunal designed to shed light on human rights abuses of parties who lack access to justice, fracking practices constitute “deadly, large-scale experiments in poisoning humans and nonhumans that the fracking industry is currently conducting in violation of the Nuremberg Code.”1 The judgment is particularly damning: the nations of the world wrote the Nuremberg Code after World War II to forbid that any government, ever again, would experiment on human beings the way the Nazis did in the death camps.

Moreover, the wide-scale contamination of fresh water is a violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees that “everyone has the right to life, liberty and the security of person.” These are not just words; these encode the moral consensus of the nations of the world, with none dissenting—an extraordinary agreement reached after World War II. The declaration sets hard ethical boundaries, minimal standards of human decency, recognizing that, as in its preamble, “disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind.”2

Clean water is a necessary condition for the exercise of the guaranteed right to life. Thus, UN Resolution 64/292: “The General Assembly… recognizes the right to safe and clean drinking water… [as] a human right that is essential to the full enjoyment of life and all other human rights.”3 When fracking contaminates drinking water, it is an encroachment on this right. When fracking contaminates a river or stream that people depend on for drinking water, that is an encroachment on this right. When fracking fluid sickens an unborn child, a child, or an adult, that is a clear violation of the rights to life, liberty, and security of person.

Clear enough. But when people protest against the violation of their right to fresh water, they run up against the violation of other rights—the right to peaceably assemble and speak their minds. In fifteen states, soon to be twenty-two, it is a felony to “impede”—literally, to make forward progress more difficult—the operations of a pipeline or power plant. Even as fracking companies weaponize the water, they militarize law enforcement, arming local law officers with the surplus equipment of military forces and degrading the processes of democratic decision-making.

…

But as important as these violations of human rights are, it’s when we go down with the drills into the seams that we encounter immorality even more grave, and that is the fracking industry’s assault on the sanctity of water and the life-sustaining systems of Earth.

If there is anything on Earth that is sacred, it is water. Sacred means many things to many people. To me, it is the good English word that describes what is irreplaceable, beautiful, mysterious, powerful, essential, astonishing, and beyond human control or creation—sacred water, holder of light, holder of darkness, holder of all life. If water is sacred, then when fracking companies take it from Earth and from the people who depend on it, that is a sacrilege—sacrilege, the stealing of sacred things, from sacra, sacred, and legere, to steal. And destroying that water, wasting it, despoiling it, using it as an agent of destruction? That is a profanity, literally, pro-, outside of, fanum, the temple—taking lightly the attributes or acts of God. Water has a terrible power; when oil industries take it lightly, when they profane it, when they tease it with unthinking hubris, when they fail to show it proper respect or fear it fully, they create consequences of cosmic proportions.

If we persevere, if we hold hard to what is right and name what is wrong, if we wrest control of water from extractive industry, our children may find a time when water can reclaim its innocence and rain remake the world.

Finally, we come to the truly world-destroying power unleashed when fracking industries transmogrify water into an explosive device. When fracking shatters ancient layers of rock, it releases the carbon that sank into prehistoric swamps and has slept there for two hundred million years, trapped in its underground crypts. Once freed by the explosive force of water, the carbon surges, snakelike, up the wellbore: crude oil and natural gas. After great amounts of money change hands, the carbon is burned. That releases carbon dioxide that traps enough heat in the atmosphere to irredeemably disrupt the systems that sustain life on Earth.

What systems? As we now know to our sorrow, climate warming caused by burning oil and gas disrupts the patterns of the wind, the force of the waves, the great currents in the seas, the reliable rivers of rain, the patterns of heating and cooling that allowed life to evolve in all its earthly sweetness and ferocity. Now, truly, the oil industry has unleashed watery weapons that lash out blindly, striking far more fiercely than a water cannon. Floods, hurricanes, rising sea levels, drought, saltwater intrusion: once water is made a weapon, it cannot be controlled. Climate chaos is the ultimate aggression, as the oil industry in so many ways enlists water as a foot soldier in its war against the world.

…

My friends and I found a strip motel not far from the fracking fields. Part of a man camp for the roustabouts, the beds smelled of cigarettes and hard use. Recoiling into the night, we sat under the flashing light of the motel’s marquee. On the western horizon, methane flares glared off black clouds that rolled eastward until they erased the stars. The wind rose, the electricity blinked out, and rain began to fall. Big drops plonked on the dust, and suddenly the world was nothing but darkness, mud, and sage, as if we had been carried in our aluminum lawn chairs back into the mysterious eons when water created the world.

If we persevere, if we hold hard to what is right and name what is wrong, if we wrest control of water from extractive industry, our children may find a time when water can reclaim its innocence and rain remake the world.

Notes

1. Thomas A. Kerns and Kathleen Dean Moore, eds., Bearing Witness: The Human Rights Case against Fracking and Climate Change (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2021), 305. The full text of the Advisory Opinion of the Permanent Peoples’ Tribunal on Fracking and Climate Change can be found at https://www. permanentpeoplestribunal.org/category/jurisprudence/?lang+en.

2. For the full text of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, see the United Nations web page: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of- human-rights.

3. UN Resolution 64/292, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/687002?ln=en#record- files-collapse-header

This essay by Kathleen Dean Moore has been reprinted with permission from “Water,” volume three of the five-volume anthology “Elementals,” published by the Center for Humans and Nature, 2024.