Is high-tech war that can annihilate human civilization and nature on a global scale really a viable response to conflict in the 21st century? The traumatic wounding of war is so deep that it calls for more than antidepressants or stress management. Dr. Edward Tick’s heart-rending experience shows us that transforming the demons of war can lead to a redemptive path of healing and reverence for life.

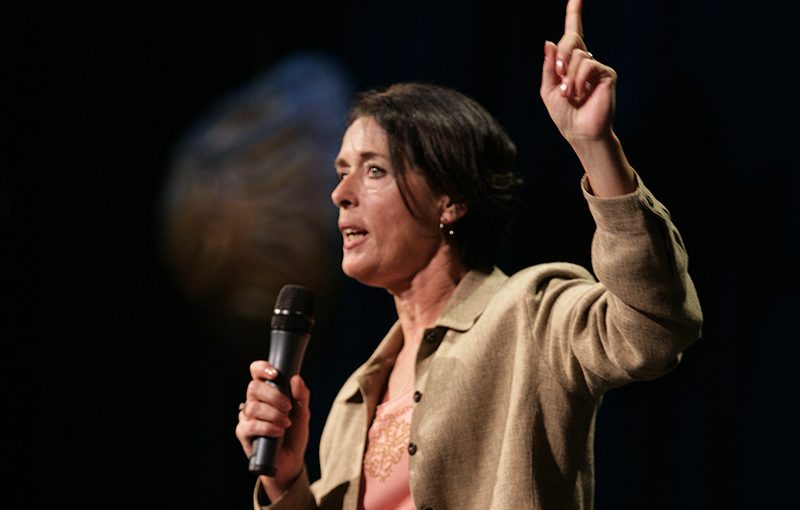

Daughters of Thoreau: Not Too Well Behaved | Julia Butterfly Hill, Diane Wilson, and Terri Swearingen

On his deathbed Henry David Thoreau said his only regret was being too well behaved. Julia Butterfly Hill, Diane Wilson and Terri Swearingen, three of the most imaginative, inspiring and courageous direct action heroines of our era share their experiences and show us how courage and commitment can stop mountains from being moved.

True Biotechnologies: Nature’s Best Climate Change Solutions | Janine Benyus, Stephan Dewar, David Orr and Jay Harman

Some of the best minds on the planet are busy cataloguing possible solutions to the crisis of climate chaos. Scientists, entrepreneurs and educators on technology’s cutting edge offer a broad array of bio-based solutions that are already working to transition us to a truly sustainable civilization. Biomimics Janine Benyus, Stephan Dewar, David Orr and Jay Harman offer a smorgasbord of startling solutions based on nature’s genius.

Explore our Biomimicry media collection >>

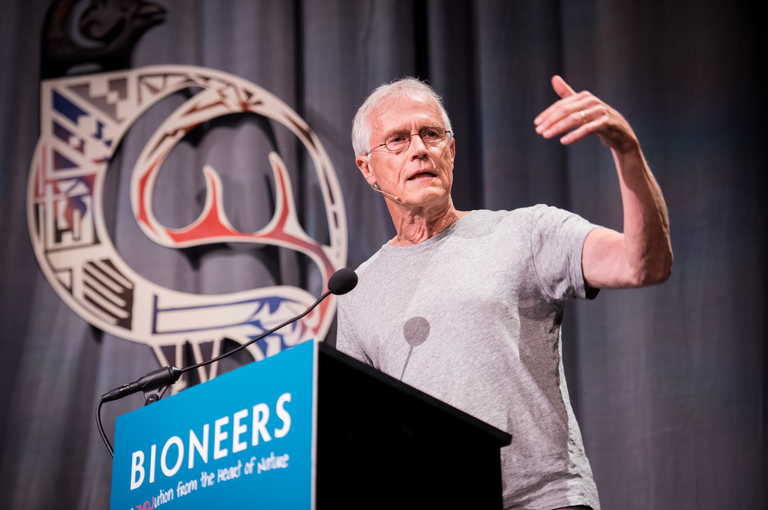

Restoring Life’s Fabric: The Biological Bottom Line | David Suzuki

Is the economy the most important thing? Canadian geneticist, author, and television producer David Suzuki says the economy is just a subset of ecology. Drawing on native wisdom and state-of-the-art science, he vividly demonstrates that what we do to what surrounds us, we do to ourselves, and suggests how to restore the fabric of the biosphere.

Source by Bioneers

The Clash of Civilizations: Liberation Ecology and the New Superpower | Paul Hawken

There is indeed a clash of civilizations today, between a sustainable civilization and a disposable one. Author and social entrepreneur Paul Hawken identifies a new superpower: the mighty river of global popular movements with real solutions. He tracks the unprecedented phenomenon of this biggest movement in the history of the world, the diverse face of a rising new culture of restoration, of reconciliation, of healing.

Nature and Spirit: It’s All Connected | Joanna Macy, Rabbi Michael Lerner & Matthew Fox

Global healing requires a spiritual transformation of every aspect of life. Rabbi Michael Lerner of Tikkun Magazine, author/educator Matthew Fox and Joanna Macy, eco-philosopher and scholar of Buddhism speak of the profound interconnectedness of all life and the experience of joy, courage and community we need to engage in the healing of the world.

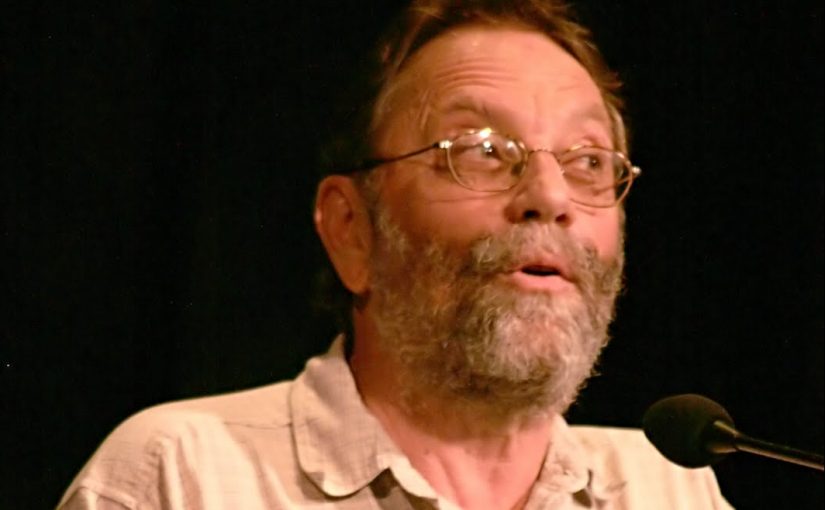

Genetic Engineering or Genetic Roulette? | Kenny Ausubel, Andrew Kimbrell & Luke Anderson

What lies behind the fascination to tinker with the building blocks of life? Kenny Ausubel and Andrew Kimbrell shed light on the disturbing genetic engineering debate and activist Luke Anderson reports from the successful campaign that has derailed the spread of “biological pollution” in Great Britain and Europe.

Thinking Like Cathedral Builders: Green Building for the Long Haul | John Abrams

Few people realize that poor design and inefficient buildings account for half America’s energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Master builder John Abrams finds that tapping human ingenuity with a long view will serve future generations, the environment and the human spirit. The kind of green building Abrams employs necessarily addresses the architecture of communities, businesses and the human heart.

Source by Bioneers

Indigenous Peace Technologies: The Ancient Art of Getting Along | Jeannette Armstrong…

How do we create peace? What can we learn from indigenous societies who have addressed this profound question over thousands of years? From North America to the Kalahari, Jeannette Armstrong, Marlowe Sam, Evan Pritchard, Kxao=Oma and Megan Biesele share powerful stories of how indigenous social technologies have succeeded in resolving conflict, and still are.

Value Change for Survival: All My Relations | Chief Oren Lyons, Leslie Gray & John Mohawk

In these ecologically dangerous times, many call for a fundamental change of heart if we are to restore vital ecosystems. Oren Lyons, Leslie Gray and John Mohawk remind us of the values that sustained people for thousands of years in a balance that supported the land. They offer direction toward nothing less than a value change for survival.

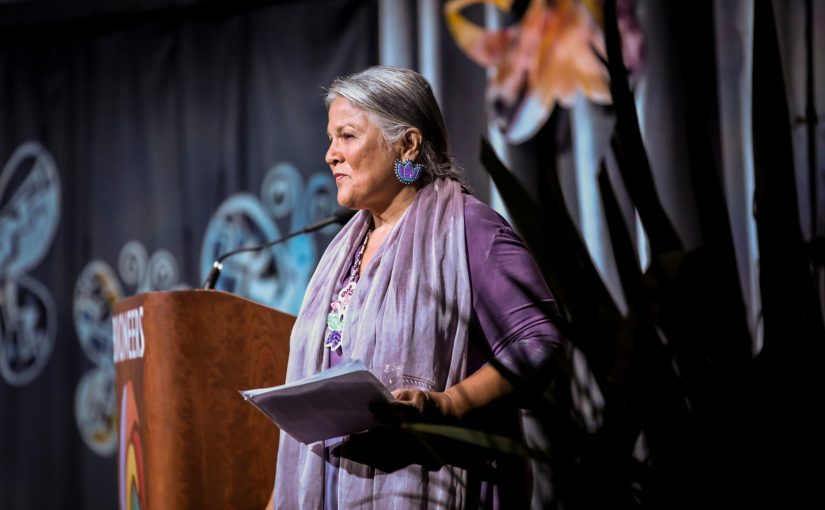

Indigeneity: Becoming Native, Staying Native | Jeannette Armstrong, Leslie Gray, and Katsi Cook

What would life be like if we could hear the land ask us to be a certain way, a way that leads us and the Earth back to wholeness and health? Native American activists, educators, and leaders Jeannette Armstrong, Leslie Gray, and Katsi Cook share an inspiring Earth-honoring vision of what it means to “re-indigenize” ourselves.

Toxic Trespassing: The Inside Story of the Love Canal Uprising | Lois Gibbs

Few people know how a hostage-taking incident transformed a shy housewife from the working-class community near Niagara Falls into one of the founding mothers of the environmental justice movement. Spark-plug community organizer Lois Gibbs traces the electrifying arc that led from sick children to an international rallying cry for human rights. Because, says Gibbs, “It is just not right morally or ethically that somebody with a corporate interest, with a dollar interest, is making a decision each and every day in this country about who lives and who dies.”