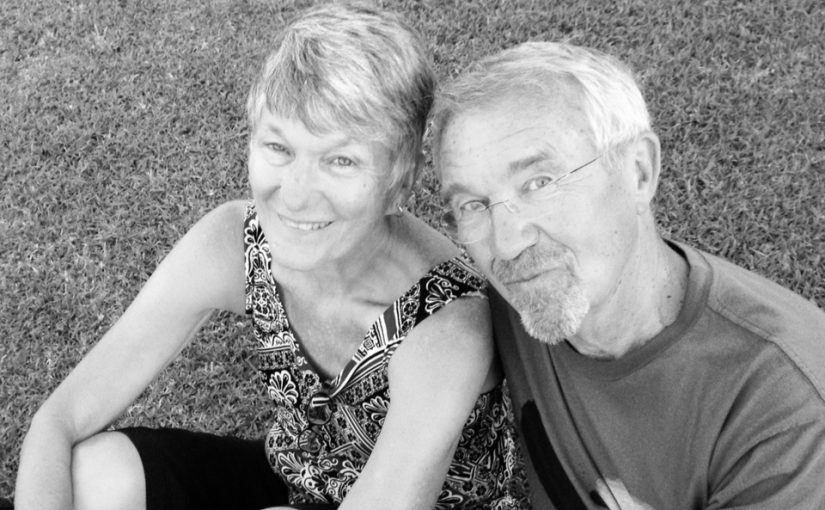

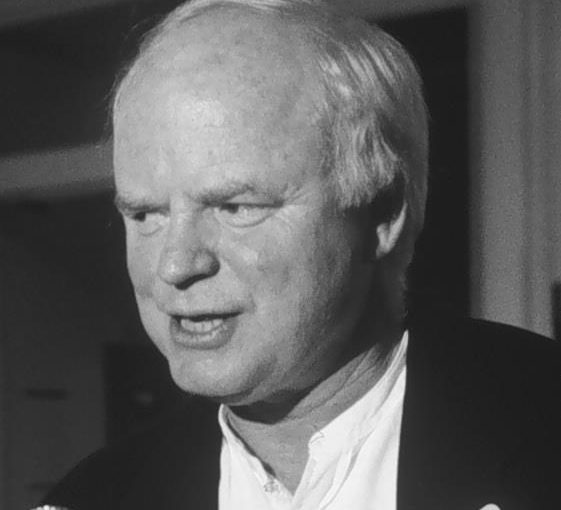

Local, organic food is growing in popularity by leaps and bounds. Beyond the benefits to the growers, our health and the land, could it become a matter of survival? Author and farmer Michael Ableman shares his cross-country journey celebrating the reverent reconnection with food and the land that is transforming how we will produce our food.

Find out more about Michael Ableman and how you can engage with his campaigns and efforts by visiting http://michaelableman.com/