The environment in countries of the global South has often suffered most, and how these nations relate to the environment from here on is a make-it-or-break-it factor in planetary survival for all of us. Ethiopian visionary Bogaletch Gebre depicts how the interconnecting forces of environment, economy, women, health and ecological technologies are creating a future environment of hope.

How Soil Health Affects Human Health: An Interview with Dr. Daphne Miller

Daphne Miller is an author and a practicing physician who spent time on seven innovative farms around the country to explore the connections among soil, how food is grown and personal health. Dr. Miller is a Clinical Professor at the University of California San Francisco, and a Research Scientist at the University of California Berkeley School of Public Health. Her most recent book is Farmacology: Health from the Ground Up. Bioneers Restorative Food Systems Director Arty Mangan interviewed Dr. Miller at a past Bioneers Conference.

ARTY: What was it that made you realize that conventional medicine doesn’t have all the answers for health?

DAPHNE: I was working in Salinas, CA as a medical intern and realized that most of my patients had been harmed by the environment and by the agricultural systems that surrounded the hospital, either from toxins in the soil or in the air, or from labor conditions that were unjust, or from eating foods that were too high in calories and didn’t have enough nutrients. I realized that although I had been in medical school for four years and done all this training, that I didn’t have the tools to help address those issues of the environment, the food system, diet and unjust working conditions.

ARTY: What turned your attention to soil?

DAPHNE: I realized that if I was going to trace all of the disease that I was treating to one thing, it was soil and mistreatment of soil. It was either planting the wrong things in the soil or spraying the wrong things on the soil or using the wrong mechanized practices for treating the soil or having policies that were affecting both farm workers and even the local economy in an adverse way. Everything, in a way, traced back to soil.

ARTY: You actually worked on some farms.

DAPHNE: I started to realize that our food system was broken. It was not a system that was nurturing us or protecting us, but rather was a system that was making us sick and harming us. I started to look to the medical literature to understand what the models were for growing food and for distributing and processing food that could actually be healthy. I remember the day I went to PubMed, which is one of the premier medical research search engines, and I put in the words “soil health” and “human health” to see what studies would come up. I was hoping that I’d find preventive medicine studies on agriculture and health. Pages and pages of studies came up, but they were all about toxins, lead, heavy metals, tetanus, sewer sludge, etc. Reading these studies, it seemed like soil was a horrible dangerous place. Certainly not a place that you would want to eat from, or let your child play in or stick their hands in or a place where you would spend your profession digging in soil. There had to be another model, a model that actually created healthy soil and healthy farms to protect us, and yet there was absolutely no research on the health-promoting impact of agriculture.

That’s when I decided to go out and learn from farmers who were farming in a regenerative or sustainable way so I could start to understand from the farm perspective what these models looked like and begin to ask questions that span between the soil and agriculture and ourselves. I wanted to research how farming in a healthy way influences personal health.

ARTY: What did you learn on those farms that informed your medical practice?

DAPHNE: I would say it gave me more of a systems approach or a holistic approach to treating patients because good farmers are not reductionist in the way they think. They think about using many different tools and different natural systems together to farm in the best way possible to protect the soil and protect the microbes in the soil and generate healthy food. I started to borrow from that model in terms of thinking of treating my patients. What are the ways we can actually use the natural system to promote health?

A lot of the work I do is not in the clinic; it is as a healthy farming advocate working on issues around policy, pushing research, and thinking about how hospitals and the medical system can actually support healthy agriculture, both through aggregate purchasing and through advocacy and policy. The clinical piece is only one slice of the pie, but there’s a lot of ways to connect health and farming.

I also learned, from family farmers around the country that farmers are using practices, like tilling and spraying chemicals, that are destroying soil and directly destroying our health.

ARTY: How does tilling or plowing the soil affect our health?

DAPHNE: Tilling puts particular matter or PM10 into the air. When farmers till, there are much higher rates of asthma and allergy and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. But tilling also destroys the unpaid workers – the soil microbes – whose job it is to scavenge nutrients from organic matter in the soil, and pass it on to the rootlets of the plants. These nutrients then go into the plants and ultimately nourish people. We have a lot of evidence that when you lose biodiversity in the soil, you lose the nutrient value of those plants. By tilling, we are basically stealing our own nutrition.

ARTY: Is there is a relationship between a healthy soil biome and a healthy intestinal biome?

DAPHNE: We understand the links theoretically and there are even some studies showing that the bacteria that are in the soil might influence the bacteria in our gut, but the science is not well established yet. But there are lots of plausible connections, including the fact that if you use a lot of herbicides and pesticides in the soil, they actually get transported via the food into our gut, and can kill off our own bacteria, much the same way that antibiotics do.

But I don’t want to make false claims. You are asking about exactly the area where we need a lot more research. Unfortunately, to do that research requires human microbiologists and soil microbiologists collaborating together and asking questions that span both environments, but it is very challenging to get researchers to move outside their comfort zone and ask questions that are a little more expansive.

ARTY: There is more science that supports the idea that a healthy soil biome will deliver better minerals to the plant.

DAPHNE: Yes. Now that is something that, once again, we still need to do more research on in order to establish exactly what a healthy soil looks like. We haven’t even come to a universal definition of how to measure soil for health. What does soil health look like? The USDA’s Soil Initiative is trying to publish standards for healthy soil. Obviously, we know it’s going to look different in Kansas or in California, but at least we need some principles and some basic criteria that have to be met in order to call a specific soil a healthy soil.

We do know that plants will get a better uptake of nutrients from a very alive, biodiverse soil with a good ratio of fungi to bacteria. That’s because the higher the diversity of these fungi and bacteria, the more likely it is that there will be the right bug to do that specific job of harvesting that nutrient and passing it on to that specific plant, kind of a lock-and-key relationship that exists.

ARTY: What is your take on the studies comparing asthma rates of city kids and farm kids?

DAPHNE: This research is really exciting for me and it is an example of that kind of discipline-spanning research that is needed. It initially started with allergists in Germany who were trying to understand why it was that their patients, who grew up on sustainable Bavarian farms, had such low rates of asthma and eczema and even certain chronic autoimmune diseases, especially when compared to kids living in urban areas in Germany, but also compared to kids living on more conventional farms. What they found through their research was that it looked like it was the biodiversity of microbes on those farms and in the soil and in the milk and in the cowsheds and on the mattresses and everything else that seemed to make a difference. The kids on those sustainable farms were exposed to a much larger diversity of microbes. The microbes, in some way, were helping to stimulate their innate immune system. Maybe even early on when those kids were developing in utero in their moms, they were being protected. The microbes were sort of training the immune system so that it was able to distinguish friend from foe and not to overreact to allergens and so on.

Most autoimmune processes, even allergies, are just our immune system overreacting to things that it shouldn’t. It looks like having that early exposure to a diversity of bacteria really made a difference. Studies in the US have similar findings.

ARTY: More and more, there’s a growing awareness about the risks of the use of antibiotic soaps in the home. How does that relate to this conversation?

DAPHNE: Oh, it truly does. For generations people were really paranoid about germs and did everything they could to sterilize, and for with good reason. People used to die in scores from things like polio, tetanus, you name it. In the 1950s we really went overboard and started to lead unbelievably sterile lives, where we had absolutely no contact with bacteria. Everything was sealed and packaged and pasteurized and boiled and so on, which corresponds to when we started to see an uptick in a lot of autoimmune diseases.

I think what’s happening now is there is a recognition that you need a healthy profile of bacteria in your life; it doesn’t matter if you live in an urban or a rural area, you need it. There’s much more of an effort to expose kids to it, with playgrounds where they’re encouraged to play in healthy dirt, and the idea that urban farming and getting your hands in the soil, no matter where you are, is really important.

Doctors are getting on board too and prescribing antibiotics a lot less. Of course, they’re still prescribing it for pneumonias and kidney infections and things where you absolutely need it, but we used to prescribe it for things that you’d think maybe at some point might develop into an infection, maybe. You’d send someone home with 20 days of antibiotics. It was just completely overboard. Now they’re giving shorter courses of antibiotics that are less broad spectrum and are more specific for what’s needed. I think that there has been a big change in the medical profession.

Where there hasn’t been enough of a change is in agriculture, and we use way too many antibiotics in agriculture. We use it basically as a growth promoter in conventional agriculture for livestock and chickens and so on. There is research to suggest that a lot of antibiotic resistance in humans might be coming from agriculture. So, that is a place that still very much needs to change. I think that San Francisco is going to become one of the first cities in America to require antibiotic labeling on meat, so you’ll understand whether that meat was treated or not with antibiotics so that consumers can really demand antibiotic-free products.

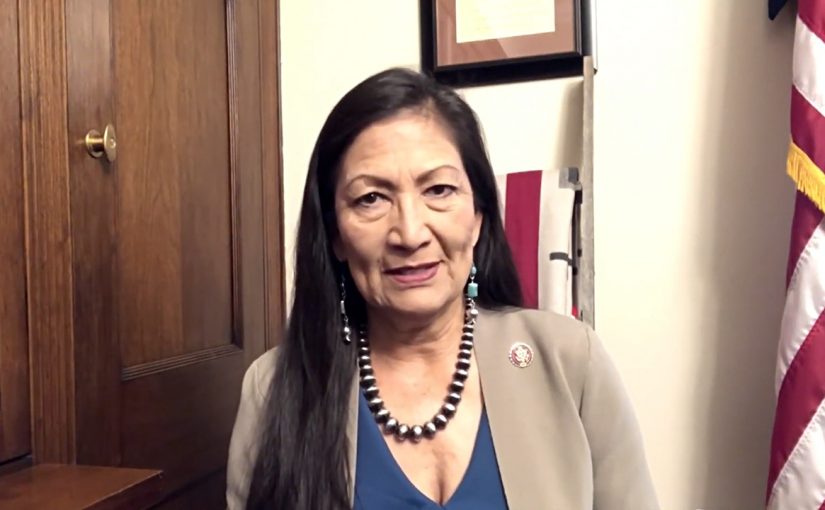

Congresswoman Deb Haaland (NM-01) on 30 Years of Bioneers

Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal Addresses Bioneers 2019

Environmental Inclusivity: Heather McTeer Toney on Social and Climate Justice

As the first African American, first female, and youngest mayor of Greenville, Mississippi, Heather McTeer Toney has seen firsthand how people of color and low-income communities are some of the most vulnerable populations to the consequences of climate change. She advocates embracing climate justice as the social justice issue of our time. Toney is now leading an environmental inclusivity movement in her work as National Field Director of Clean Moms Air Force, an organization of more than one million parents united in the fight against pollution to leave the next generation a healthy planet.

Following, McTeer Toney discusses what it means to be an environmentalist today.

What is an environmentalist? Think about it for a moment. What is an environmentalist to you? I did a Google search earlier this week: “What is an environmentalist?” On the first page under images, this is what it came up with.

I don’t see any color. I see trees, I see people hugging trees, I see whiteness.

This is important to note. When we think about what an environmentalist is, if this is the general image and lens through which we see environmental engagement — and it’s a lens of privilege, a lens of singularity, a lack of community — then it’s no wonder words like “environmental justice” or “climate justice” create dissention.

In 2009, The Washington Post ran a story on my city. I was mayor of Greenville, Mississippi, and they’d been working with us for some time. Being young and energetic and ready to solve all the world’s problems, I figured I was going to tackle brown water in my community. So at the ripe old age of 27, I decided that running for mayor and focusing on this as one of many issues in my community would attract some attention. And it certainly did; it got the attention of The Washington Post.

On a Monday morning, above the fold, people saw the face of a child in a bathtub full of brown water. And right below that fold, they saw a picture of me, looking serious about rectifying this issue in my community.

After that, I was visited by Lisa Jackson. She was the first African American administrator for the U.S. EPA. She said, “You know you’re working on environmental justice issues, right?” She said, “You know the mission statement of the EPA is to protect human health and the environment, right?” That was my advent into eventually working for the EPA. I became the regional administrator for the Southeast region to do community-facing work for community problems on climate and the environment.

But herein lies the problem. Because if the lens that people see the environmental work through is colored, then it doesn’t allow for solutions grounded in things like cultural competency and realistic outcomes.

If there’s anything that being a mayor and a regional administrator has taught me, it’s that you had better have an answer for the people, and you have to have solutions. You must be solution-minded, and there’s not a lot of time to sit around and have meetings when the people need a solution. That’s the same thing that we have an issue with right now.

I know you know the results from the IPCC report, and you know what’s going to happen in terms of global climate change and crisis and emergency. There are all of these solutions out there. But then we talk about the solutions in ways that people cannot grapple with and embrace.

Perfect example: The IPCC report has said that one of the things we should do to help reduce carbon emissions is to not eat as much meat. It is a solution that has been touted and that a lot of people have gotten behind. I am a black Southern Baptist woman from Mississippi. I cannot go into my church and say we are not going to have chicken and bacon. It’s not going to work. I’m from Mississippi — you can’t tell me how to grow food. My ancestors did it. You can’t talk to me about what I should be doing with respect to the soil, because I taught you.

It is critically important that we have these conversations through the lens of the people who have lived these experiences. Privilege keeps us from doing that because it doesn’t allow us to listen to one another. And that’s what we must begin to do. We have to begin to listen to one another.

This is one of the things that I love so much about Moms Clean Air Force, an organization that I’ve been blessed to now be a part of. It’s because mothers do what mamas do. We are going to protect our babies to no end. Whether we are protecting them from the impacts of climate, or we are protecting them from gun violence, we are protecting all of our children, and we recognize that climate has something to do with all of it. It’s called bringing people to the table. If you’re a mother, you know how to make children play together. You know what’s happening when they’re fighting. If you’re a mother, a grandmother, play cousin, auntie, you know how to do this. This is not rocket science.

We have to realize the natural things that we have within ourselves tell us what to do. It’s the reason we are finding that moms are becoming more engaged on a political level, where they’re being appointed to office. And as I have said repeatedly, if you can be the secretary of the EPA, you can be the secretary of the Department of the Interior.

We’re realizing that our voices are required at this moment. It’s not an option. It’s a requirement. It’s like when you hear the kids in the back room, and they’re making a whole lot of noise. That’s all right. But when you hear something break, and it gets eerily silent, you know you have to get up and go into that room. What we’re saying as mothers is that we are now getting up and going into the room.

Those are the rooms that we sit in. We go into the rooms where the policymakers are, where we are testifying before Congress, where we are saying this is what is happening in our communities. This is not an option. We shall be on record because we have something to say, and we recognize fully that if it is not said by us then it will not be said and shared. These are the places where we feel strongly that all of our mothers and grandmothers and grandfathers and aunties and play cousins, anyone who has an interest in seeing the welfare of our children be protected from the impacts of climate change and air pollution, they must be in these places.

And we see an amazing impact. Sometimes you just need things to be done in the language that you understand. And we do that.

We make sure our children are given the microphone to say what they need to say. That’s why this work is important. I do this work because I’ve been doing it for years, and I understand that there are a lot of places that we could be, but this is the social justice movement for our time. This is it. And it’s now.

Marin County Honors 30 Years of Bioneers

This talk was given at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

Mary O’Mara of Marin Link and Marin Arts introduces Marin County Leaders, including Congressman Jared Huffman, who sends a video greeting to Bioneers.

Also featured: Carol Mills from Senator Mike McGuire’s District Representative’s Office, Henry Simons from Assemblymember Mark Levine’s office, District Supervisor Damon Connolly, and San Rafael City Council Kate Colin.

Jerry Tello: Recovering Your Sacredness

This keynote talk was delivered at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

Our society is experiencing profound levels of stress and anxiety, a public health crisis that’s triggering unresolved traumas in many people, resulting in widespread uneasiness, poor public health, social dysfunction, and alienation, as well as high levels of violence, suicide, and substance abuse. Through traditional stories and personal reflections, Jerry Tello, raised in South Central Los Angeles, co-founder of the Healing Generations Institute, a celebrated leader in the field of the transformational healing of traumatized men and boys of color, shares his approach to generating the “medicine” necessary to shield ourselves from this toxic energy, and offers us pathways to discover, uncover and recover our sacredness and return to health and wellbeing.

Jerry Tello, of Mexican, Texan and Coahuiltecan ancestry, has worked for 40+ years as a leading expert in transformational healing for men and boys of color; racial justice; peaceful community mobilization; and providing domestic violence awareness, healing and support services to war veterans and their spouses.

To learn more about Jerry Tello, view his full bio here or visit the Healing Generations Institute.

Read the full verbatim transcript of this keynote talk below.

Transcript

Introduction by Héctor Sánchez-Flores, Executive Director, National Compadres Network.

HÉCTOR SÁNCHEZ-FLORES:

Buenos días. Good morning and afternoon, as we get started here. My name is Héctor Sánchez-Flores and I represent the National Compadres Network. I’m humbled to be here to introduce your next speaker, a man that I have known for nearly 25 years but whose work is approaching over 40 years of dedication to community.

Maestro Jerry Tello. If you’ve never met him, I’ll share with you a few items that I think that rarely get highlighted about his work, who he’s connected to, and what drives his passion and his mission as I’ve observed over 25 years.

He’s connected to a wonderful partner, Susie Armijo, and together they cultivate and support work about healing across this country. Together, if you ever have the chance to see them work together, you will see magic happen as they help us uncover, help me uncover, those things that I’ve overlooked, the medicine that I carry.

But the other parts of Maestro Jerry Tello that are critical to understand is that he is a father to Marcos, Renee, Emilio and grandfather to Amara, Naiya, Greyson and Harrison. And if you ever want to see him light up, hear him tell the stories of how those grandchildren truly manipulate the best of him. [LAUGHTER]

What he’s reminded many of us along the way is that within us we carry medicine. And his stories and the narratives that he creates are powerful reminders of the things that we overlook about ourselves. And I always am grateful of the things that he discovers about himself through his stories because it usually illuminates those corners of our lives that remain dark and sometimes unseen.

I’m grateful for everything he does for the community to remind us that our culture here’s La Cultura Cura, and I look forward to hearing his words today as I have for the last 25 years because every time I hear him I am slightly different and walk away with a new understanding of the teachings and lessons.

Without further ado, I’d like to introduce Maestro Jerry Tello. [APPLAUSE]

JERRY TELLO:

Ometeotl, Noxtin, Nomecayetzin. Good morning, relatives. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] I want to begin by thanking Creator, another day of life. Thank our native relatives of this land for the privilege, the blessing of us being here. I want to thank you all for showing up, for choosing to bless us with your presence this morning. Thank you, Hector, who in himself is a wonderful teacher.

My people, I come from—My father’s name is Jorge Perez-Tello. He’s Tampilan Coahuiltecan from Yanaguana, commonly known today as San Antonio. [LAUGHTER] Our people have been there for many generations, and my daddy was the oldest at 15. My mom comes from Chihuahua. She’s Mexican Tarahumara, and she came from a smaller family, not as big as my dad, and she was the oldest of 14. [LAUGHTER] That’s not like we didn’t believe in family planning, we just plan big. Right? [LAUGHTER] My grandma said every kid’s a blessing. We had a lot of blessings. You know? [LAUGHTER]

But we ended up, after all the travel back and forth, I was ended up—even though I was born in those areas, I ended up being raised in Compton, so I’m straight out of Compton. [LAUGHTER] I grew up in a barrio neighborhood, black/brown neighborhood. And I guess they would consider it high risk, delinquent, impoverished. But in that neighborhood, in that neighborhood, the one I grew up in, that I didn’t know we were poor, because my mama never said we were poor. She just said eat those beans. Right? [LAUGHTER] And I would complain, “Why do we gotta eat beans again, Mom? Why can’t you make something else?” “Ah, be quiet, just eat the beans.” “But why can’t you make something else? …those beans…” “Ah, you ought to be glad you have beans. People in other countries don’t have nothing but…Kneel down.” “Why?” “Ask for forgiveness for…” “I’m sorry, God, for complaining about beans.” [LAUGHTER]

You know, my mom’s crossed over a number of years ago, and I miss my mama’s beans. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] Didn’t realize it when she was making those beans. She got those beans, and she had us sit with her, and take out the little rocks in those beans, and she’d say, “You’ve got to pray. You’ve got to pray when you take out those beans, because that’s part of what you’ve got to do in your life. You’ve got to take out those parts that are not going to feed you.” She’d get those beans and put them in the water, and put the onion, and the garlic, and all of that, and she’d say a little prayer. I didn’t realize that that was a recipe that her mama gave her, that her mama gave her, that her mama gave her. I didn’t realize in that little bowl of beans that she gave me were generations of medicine.

But what happens sometimes when you live in this world, you don’t appreciate those things. We don’t recognize in those traditions, those ways. And I lived in Compton, in a crazy neighborhood, a lot of things going on. I guess you consider a lot of risk factors. My house, a lot of kids, always a baby crying [MIMICS BABY CRYING] all the time. [LAUGHTER] I would trip when the teacher says go home and find a quiet place to study. I’m like, where? [LAUGHTER] If you’re really motivated, you’ll find—Like where? [LAUGHTER] If you really want to do well in school…Like where? [LAUGHTER] And I guess that’s why my daddy talked loud.

I had a loud talking dad. [MIMICS FATHER YELLING] My friends go, “Is your dad mad?” I said, “No, dude, that’s the way he talks all the time.” [LAUGHTER] Kind of a trip for a social worker to come to my house. You better send them to—anger management’s developmentally inappropriate for these kids. No. [LAUGHTER] That’s when my dad was fine when he talked loud. He especially talked loud when he saw relatives come over. When people came to him that saw him, embraced him, and honored him.

I also saw what happened to my dad when he was in places where people did not honor him. And as a little boy, it confused me, because we were taught to honor everyone. I was taught by my grandma. And in that house I lived with grandmas. My mom’s mom and my dad’s mom, not both at the same time. You don’t put two grandmas together, I don’t care how old they are. [LAUGHTER] No, no, no, no. They got their ways and they want you to be their favorite.

But my little grandma, my mama’s mama, she was about that tall, and I thought she was kind of crazy because she did strange things to me. One of the strange things she did, she’d get up every morning at 4:00 in the morning. To me that’s crazy, grandma. Why don’t you sleep later? You don’t got to go to school. You don’t got to go to work. Why don’t you sleep? No, she would get up at 4:00 and I didn’t understand. She’d go out and talk to her plants. “Good morning. How you doing? Buenos días.” And then she would give them water. “I’m going to feed you water. Please, I’m going to take a little bit of you.” She would talk to these plants, ask for permission. She says, “I need to take a little bit of you, because my grandson is sick. Will you help me heal him.” I thought my grandma was crazy. Why do you talk to plants? Why do you ask for permission, just take it. [LAUGHTER] And then she’d take it and make this yukky tea and give it to us, and…[LAUGHTER] And it’d make us better. I didn’t understand. I thought my grandma was crazy. She got up at 4 in the morning. Didn’t understand at that time, but that’s a sacred time, that at 4 in the morning is when grandmother moon and grandfather sun comes together. They sing that song together, that rhythm, their vibrations together. That’s where creation happens again. That’s regardless what happened the day before, we have another day.

So my grandma would get up at 4:00 in the morning. And she’d go in that crowded house where all of us lived. And there’s a little hole in the wall, and in that little hole in the wall, my grandma had her sacreds, had her candles. And she had all kinds of things from her sacred natives to her Catholic—she put them all there. She used anything that would get her closer to that sacred. The little pillow on the ground and she’d kneel down right there on that pillow. And you could almost tell how many problems we had because the more problems we had, the longer she’d stay right there. [LAUGHTER]

But after she finished, after she finished praying, sometimes an hour, and hour and a half, sometimes two hours, she’d come to the room where all of us kids were sleeping. And my grandma would bless us up. She’d bless us all up.

And I used to hate it. 5:30 in the morning, “Grandma, why are you waking me so early? I was having a good dream.” [LAUGHTER] “You messed up my dream, Grandma. Why? You blessed me last night before going to sleep. Is it still good for now?” [LAUGHTER] “And you’ve got to bless me when I go to school? Why do you always got to bless me? Do I got the devil in me or what?” [LAUGHTER]

I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand the significance of blessing. I didn’t understand the significance of someone that was connected to the sacred saying to you every day, “You’re a blessing. You’re a blessing. You’re a blessing. You’re a blessing.” My grandma would bless up the kids that were good in school, the ones that weren’t good in school, the skinny kids, the fat kids, the stinky kids. She didn’t care. She’d bless us all up.

And I didn’t understand why my grandma needed to inoculate me with the spirit of our ancestors, with the message of great, great ancestors that says Creator doesn’t make junk. Creator only makes blessings. And so she would inoculate me and bless me up before I left.

My grandma knew something that I didn’t know. She knew that I would go in the world that was not going to see me as a blessing. That many times just because of the color of my skin or how I was dressed or my hair, or how I looked, they already had a plan to lock me up or deport me or put me out of—take me out. That when I went in classrooms, they were already going to put me in the back of the room and expel me and suspend me. My grandma knew that this world was wounded and didn’t appreciate what we call in my language In Tloque Nahuaque which means interconnected sacredness. My grandma knew that just a look of people I could feel their energy. So she blessed me up. And she blessed me every day and as many times as she could.

And so I want to take a moment here, because we’ve got a lot of work to do, but we can’t do the work unless we’re grounded. We can do the work but it may not be sacred work, it may be angry work. And it may be work that divides us and doesn’t bring us into that In Tloque Nahuaque. We have to be grounded. So I want to just take a moment, and I want to invite your ancestors in the room.

I can’t imagine what my great-great grandmothers, great-great grandfathers did, what they had to go through, what they had to deal with, what they had to put up with, and they didn’t give up. And your ancestors did the same thing. All of your ancestors struggled, they had difficulty, and they didn’t give up. But like your grandmother and my grandmother, they all had a dream. And I’m a grandfather now. My dream for my grandkids is that they’re going to have a better world, they’re going to have more blessings and less pain, and less struggle.

So inviting your ancestors in the room, and maybe you didn’t have a grandma like my grandma, maybe you didn’t even know your grandma, maybe your grandma or grandpa were wounded, they were so wounded they could barely just survive and just live another day where they didn’t have the energy to reach back to those traditions and pull them out. Or maybe they were so ashamed of who they were that they left those traditions behind, and so they didn’t give you that blessing tradition. Maybe your grandparents were separated from you because of racism and discrimination and deportation, and all of those things, so you didn’t even know them. Maybe you never got the blessing.

So I want to stop for a moment. And I want to say to you on behalf of your ancestors, on behalf of your great grandmothers, on behalf of your great grandfathers, that you are a blessing just the way you are, as you sit there today. You don’t have to know any more, you’ve got to lose weight, you’ve got to color your hair, you’ve got to do none of those things. The sacredness lies within all of us.

And my grandma would show that in her food. She would cook. And I lived in Compton so I had friends. My best friend was Tyrone Mosley, and he would come over usually right around when my grandma was cooking. [LAUGHTER] Say, “Jerry, you want to play?” [LAUGHTER] “Oh, I know why you want to play right now, because my grandma’s going to cook, huh?” “No, I just want to play.” And then my grandma would come out and say Quien Quiere comer which means who wants to eat. Tyrone would raise his hand like that. I don’t know where he learned Spanish from. [LAUGHTER] She would say Pasale mojo which means come in my son, and he walked in. Where did he learn Spanish? There were no spanish classes back then, no ESL classes. [LAUGHTER] And she called him mijo, which means my son. My grandma called the same thing to Tyrone as she called to me, because in our traditional way, all the children are your children.

In my family, we were all related. In second grade they told me to draw my family, I’d draw six grandmothers. “How do you have six grandmothers?” “I don’t know, I just call them all nana.” [LAUGHTER] I said, “All the great people are my grandparents.” [LAUGHTER] Anybody my parents’ age, my uncle and aunt, anybody my age was my cousin. And that was cool, except I have a fine cousin named Monica at 13. I wish she wasn’t my cousin, but she was my cousin. [LAUGHTER]

And the thing is, when people are related to you, you treat them different. My daughter goes to a school, my granddaughter goes to a school in Hawaii. Her native Hawaiian relatives. And they start the day when the elder comes and brings them into a circle all together and sings a chant and brings all their spirit together. And my granddaughters call their teachers auntie. Those traditions of us being related.

So my grandmother would take Tyrone and sit us together and bless him up too. Blessed him in that way too. And then, as in every family, there are kids that sometimes cooperate and some that don’t, some that cry a lot, and I had responsibility, you take care of your nephew. And one of my nephews, Ronnie[ph], was a crybaby. I don’t know if you had cry—you might have been the crybaby, I don’t know, but he cried for everything. And I was supposed to be watching him. He’s in his crib. I can hear him. [MIMICS BABY CRYING] And my grandma says, “What’s wrong with Ronnie?” “Nothing, it’s just Ronnie.” [LAUGHTER] “Well, go see.” “Grandma, it’s just Ronnie, it’s nothing.” And how many times do we play off when people are hurting? Do we just want to diagnose them and medicate them?

We work with a lot of kids that get expelled and suspended because they’re acting out their pain. A lot of what we’re seeing today is children younger and younger with more anxiety, more depression, suicidal. Elementary school kids. The work we do. Who’s healing the children?

And so my grandma gets mad at me because I’m not going to see Ronnie. And she comes and says, “Why don’t you—” “Grandma, it’s just Ronnie.” And she grabs me by the ear, “Come on, come on! You’re going to go help me.” And my cousins laugh, “Grandma’s got you, grandma’s got you.” And we go in the room, and as soon as we go in the room, I know why Ronnie’s crying. We walk in, I said, “Grandma, he’s got caca, he’s got poo poo. That’s why he’s crying.” And she goes up, “Come here my pretty baby.” I go, “He’s not pretty, he’s stinky, Grandma. He’s stinky.” “Come here my pretty. Come here, come here.” And she’d grab him. “Don’t grab him, Grandma. You’re going to get the caca all over you.” “Come here. No, no, no, come here, mijo, come here.” “Don’t pat him, you’re going to squeeze it out! It’s going to get on your dress, Grandma, it’s getting on your dress!” [LAUGHTER] And she gets—she says, “Come here, come here, mijo, come on, my pretty baby.” “He’s not pretty, he’s stinky—“ “Come here, my pretty baby. Mi precioso.” “Grandma, you’re squeezing it out!” Roo, roo, roo, roo, heya, heya… And Ronnie calmed down.

She’s never been to a parenting class in her life. Doesn’t know about self-esteem, about bonding, about ages and stages of development, doesn’t know about developmental…[LAUGHTER] But my grandma knows what you do with somebody that is disconnected. You don’t throw them away. You don’t disconnect them. You don’t ostracize them. You don’t minimize them.

My grandma also knows when someone’s hurting. I mean, Ronnie knew he was stinky. You didn’t need to remind him. [LAUGHTER] What he’s wondering is, Will somebody hold me in my stinkiness; will you embrace me; will you remind me of my sacredness when I’m not in balance, when I’m not good, when I’m hurting; will somebody embrace me?

How courageous are we to embrace those that are looked at as unembraceable? But in order to do that you’ve got to be willing to get it on you. And be willing to stand and sometimes kneel, because the problems sometimes are too big. For our Western mind, for our Western psychology, for our Western ideology, that sometimes we have to look up and say, Ancestors, come help me. We invite you to come in and help bless us up.

And life goes on. And my life went on. And my dad died when I was 13. My dad, that always wore a hat. He didn’t have a good hat like this. He had working hats. But he died. But I’d already been indoctrinated that I wasn’t supposed to cry. Boys don’t cry. Suck it up. The neighborhood, you know? So I didn’t cry. I forgot how to cry. How many of us have forgotten how to cry?

And when you forget how to cry, when you forget how to release, when you forget how to heal in your traditional way, not in the Western way, not in that, in your traditional way, it eats you up. Now I’m a freshman in high school and I’m not doing good in school. I’m trying, I’m trying. I’m going to school every day. I’m trying, but I’ve got an F in algebra, F in history. History I didn’t like because it didn’t say anything about me or my people, and so I wasn’t interested. And the algebra, I just couldn’t get algebra. I don’t know if you like algebra, but I mean they gave me a tutor, and when the tutor was there, I got it, but when she left she like took the knowledge with her or something. I don’t know. [LAUGHTER] So I got two Fs and I didn’t want to take it home to my mom who’s a single mom, who’s trying to raise us and doing everything. And I don’t like to see my mom cry.

So I’m walking home and I’m at the park, and I’m saying what am I going to do. And I think, well, maybe because I’ve gotten these messages that I’m not worth anything, that I’m expendable and all of that, maybe it’s better if I just take myself out. And in my neighborhood I don’t have to do too much. I just[?] walk two blocks over, claim up another neighborhood, they’ll take me out. They’ll call it gang violence. It’s not really gang violence, it’s really that I’m hurting. All I have to do is go to the corner, get some drugs, take a little bit too much.

But at that moment that I was thinking and decide I’m going to take myself out, the weirdest thing happened. I smelled something. I smelled maha. That’s what my grandma wore, that powder. She wore maha. I’m saying, Dude, why am I smelling maha. I’m not high. Whoa. And I smelled my grandma. And I felt her spirit. And I heard her say, “You’re a blessing, that life will be hard, but call to the ancestors. Call to me, I will walk with you. Your grades don’t define you. Your sacredness is defined by your lineage, by your ancestors.”

And I decided to go on, and I walked around the tree, and there was a $20 bill. And I said, “Dang, Grandma, you’re deep, man. Whoa!” [LAUGHTER]

So I challenge you to acknowledge your sacredness. But remember anyone you deal with has a lineage. You must call to that lineage, to our traditions, to our customs, to our spirits. We must recognize that En Lak Ech in the Mayan language means Tu Eres Mi Otro Yo or you are my other me; when you hurt I hurt, but when you heal, I heal. And we must take the opportunity where we can bless each other up.

The work we do is about healing. That’s what my grandma sent me to do, to share the blessing, to share the healing. And I want to acknowledge my companion, Susannah, who really is really the healer. She blessed me up before I left. She gives me the medicine. And what I recognize is that first teaching where healing comes from is the feminine. And if we don’t come back to a place where we honor the feminine in everything that we do, but even in our relationships – this month is domestic violence prevention month – and we work a lot with men, to have them to speak up and stand up, and if you’ve got wounds you’ve got to heal, we’ll be doing a workshop later on on that. But it’s part of that feminine that we all have to heal. And we all have to go forward together in that sacred way.

Again I want to thank you very, very much for who you are and all you do. And remember, if you see somebody, bless them up. Thank you very much. [APPLAUSE]

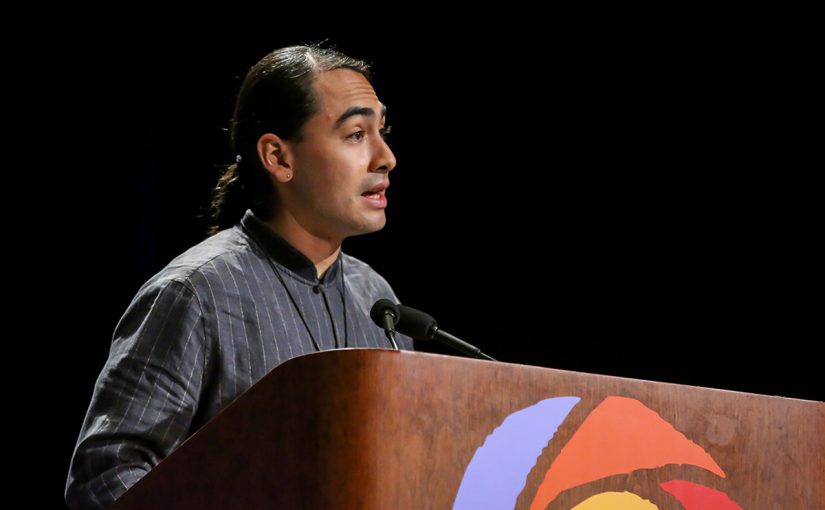

The Indigenous Renaissance | Julian Brave Noisecat

This keynote talk was delivered at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

The brilliant young writer, journalist and activist Julian Noisecat offers his insights into how, around the world, Indigenous peoples are rising in a global renaissance that holds untapped promise for a world in peril.

Julian Brave NoiseCat, Director of Green Strategy at the think tank Data for Progress, and “Narrative Change Director” for the Natural History Museum artist and activist collective, is also a correspondent for Real America with Jorge Ramos and a Contributing Editor at Canadian Geographic.

To learn more about Julian Noisecat, visit his website.

Read the full verbatim transcript of this keynote talk below.

Transcript

JULIAN BRAVE NOISECAT:

Tsecwinucw-kp, which means good morning. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] It actually literally translates as “you survived the night.” [LAUGHTER]

So at 6:00 in the morning on Monday, Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I stood on the sandy shoreline of San Francisco’s Aquatic Park, as a 30-foot ocean-going canoe, hewn from cedar and crewed by a dozen members of the Nisqually tribe of Washington, pulled out into the breakwater, its bow pointed for Alcatraz Island. The Bay glistened in the first light of the sun as Nisqually voices rose in unison above the din of the waking city, their paddles stroking the water to the rhythm of their song.

On the beach, I hugged my dad and then my mom. We’d envisioned and organized and fundraised and planned for this moment for more than two years. On Monday, our vision became reality.

The Nisqually canoe was the first to depart on the Alcatraz canoe journey, an indigenous voyage around Alcatraz Island to honor and carry forward the legacy of the 1969 occupation led by Indians of all tribes 50 years later. The Nisqually were followed close behind by the Northern Quest, its hull crafted from strips of cedars and painted with the crest of the white raven. Its crew hailed from the Shxwhá:y Village in British Columbia, Canada. They were soon joined by an umiak, pulled by an intertribal group from Seattle, as well as a dozen other ocean-going canoes from the Northwest and outriggers from Polynesia, representing people as far flung as the Klahoose First Nation in Canada and the Kanaka Maoli in Hawaii. At final count 18 vessels representing dozens of tribes, nations, and communities pulled out into San Francisco Bay that morning.

One of the last canoes to depart was a tulle boat, fashioned from reeds gathered from local marshes. It represented the Ohlone, the First Peoples of these waters. Antonio Moreno, the captain and artist, who made the canoe, paddled his craft and canoe out into the open water, the tulle reed sidewalls of his vessel barely rising above the waves. Antonio and his courageous crew pulled to Alcatraz and touched the craggy shore. His was the only vessel to make landfall that day.

The visiting canoes meanwhile circumnavigated the island, paddling counter clockwise, from south to north and back to Aquatic Park. A local ABC station captured the scene from high overhead.

The late Richard Oaks, one of the leaders of Alcatraz, once said Alcatraz is not an island, it’s an idea. The idea was that when you came into New York harbor, you’d be greeted by the Statue of Liberty, but when you came through the Golden Gate, you’d encounter Alcatraz, a former federal prison reclaimed by Indians of all tribes as a symbol of our rights, our pride, and our freedom.

The Alcatraz occupation lasted 19 months, by the time it was over, the United States had shifted its official Indian policy from one of assimilation, relocation, and termination to one of self-determination and sovereignty.

It’s possible to draw a line from Alcatraz to Standing Rock, Bears Ears, Mauna Kea, and much more. But today the occupation, if it is remembered at all, remains an afterthought. Every year over 1.4 million people flock to Alcatraz, more than any other national park in the country, to peer inside jail cells that once held notorious criminals like the Bird Man and Al Capone. The island has become a monument to carceral nostalgia, to the Mafiosos and lawmen and convicts and fugitives, not to Native Americans.

But for a day, or maybe even just a morning, the canoes made it possible to see Alcatraz as what it could be, a symbol of indigenous rights, resistance, and persistence, an island reclaimed by our elders 50 years ago, an idea, a story, and a moment of organized action that changed history.

On Monday, Courtney Russell of the […] and Haida Nations and skipper of the Northern Quest was the first to return to San Francisco. She stood in her canoe and said, “We are the original caretakers of this land. We are still here. We will not be forgotten, and we will continue to rise.”

Ashore, 85-year-old elder Ruth Orta, Ohlone elder, Ruth Orta welcomed her and all the canoes. Orta later told KQED that she was so proud to see the young people, to see the young generation participate in learning what the older generation did, she said. I love it.

Then we gathered in Aquatic Park to share songs, dances, gifts and stories about what Alcatraz meant to our families and our people. Hanford McCloud, skipper of a Nisqually canoe spoke of his auntie, Laura McCloud, who joined the occupation when she was just a senior in high school. Sulustu Moses of the Spokane tribe shared the story of one of his ancestors, a warrior imprisoned on the island after an 1858 war. When he finished, he stood and sung the war chiefs death song.

Alcatraz is not an island, it’s an idea. And with a little imagination and a lot of work, that idea moved bodies, pulled hearts and changed minds. As our people and all people face devastating crises, catastrophic climate change, growing inequality, revanchist hate, maybe the power of audacious and enduring indigenous ideas like Alcatraz are exactly what we need.

Tim Merry: Holding Up a Mirror to the Moment (Day 1)

Slam poet Tim Merry weaves highlights of Bioneers Day 1 into bardic verse.

This performance took place at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

Tim Merry works with major businesses, government agencies, local communities, and regional collaboratives to help engender breakthrough systems change through coaching, training, keynote speaking, engagement, and facilitation designed to energize and shake up the status quo. Tim is also a traveling spoken word artist inspired by poets from the ancient Anglo Saxon oral tradition all the way through history to modern poets such as Kate Tempest.

Destiny Arts Youth Performance Company | Bioneers 2019

A performance by Oakland’s own incomparably dynamic and uplifting Destiny Arts Youth Performance Company.

The Destiny Arts Youth Performance Company’s extraordinary energy, brilliant choreography and inspired lyrics have been rocking the house at Bioneers for many years. A program of Destiny Arts Center, an Oakland-based violence prevention/arts education nonprofit, the company is a multicultural group of teens that creates original performance art combining hip-hop, dance, theater, martial arts, song, and rap. It has performed locally and nationally since 1993 and has been the subject of two documentary films. DAYPC’s artistic directors are: Sarah Crowell & Rashidi Omari.

Learn more about Destiny Arts at https://destinyarts.org/

This performance took place at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

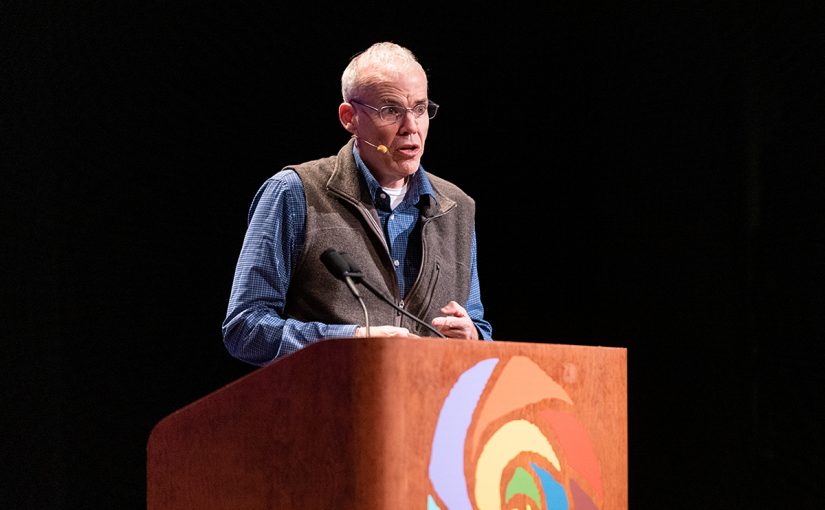

What We’ve Learned About Climate Change in the Last 30 Years | Bill McKibben

This keynote talk was given at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

Bill McKibben explores: What lessons can we draw from three decades of struggles to address the existential threat of climate disruption? What do our failures reveal about the flaws of our political system and the economic nihilism of the fossil fuel industry? What strategies are most likely to lead to greater success to save our species from itself?

Bill McKibben, our nation’s most significant environmental activist, is also a leading journalist, author and academic. A Scholar in Environmental Studies at Middlebury College, Bill’s The End of Nature (1989) was the first book for a general audience about climate change. A founder of 350.org, the first planet-wide, grassroots climate change movement, he has won slews of prestigious awards, including the Right Livelihood Award and the Gandhi Prize and Thomas Merton prizes.

To learn more about Bill MicKibben, visit his website.

Read the full verbatim transcript of this keynote talk below.

Transcript

Introduction by Kenny Ausubel, Bioneers CEO and founder.

KENNY AUSUBEL:

1989 marked a hinge historical moment. Bill McKibben published The End of Nature, the landmark book that broke the ice on global warming by reaching a national popular audience. Just months earlier, NASA climatologist James Hansen had given his first urgent testimony before Congress as the Paul Revere of global warming. He implored the nation’s political leaders to seize the decade of the ‘90s to start winding down our fossil fuel accounts to avoid runaway climate change.

In 1989, instead of its usual person-of-the-year edition, Time magazine made endangered Earth its planet of the year. There was a national awakening to the escalating hotlist of global environmental crises – freshwater scarcity, toxics, biodiversity crash, public health threats, archaic infrastructures, environmental justice, wealth extremes, and on and on. A focus on solutions began to arise from every corner of the country. Civil society surged with a renaissance of burgeoning social movements, NGOs, and citizen action. Bioneers was born amidst that ferment in 1990.

Jim Hansen had hoped to provoke a national mobilization. He did, but it came from above all, from Exxon and the fossil fuel industry, which spent the next 30 years sowing doubt and delay. It was the biggest and most expensive disinformation campaign in history. It was a catastrophic success.

Simultaneously NAFTA unleashed corporate economic globalization, triggering the insatiable plunder of every corner of the planet. Then as now, it’s the same old song. It’s the corporations, stupid. Just 100 companies called carbon majors account for 71% of all greenhouse gas emissions since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. And half those emissions have occurred since 1990, well after the industry knew full well what the consequences would be. Then as now, it’s social movements and civil society that have risen to challenge the destruction.

As a renowned and influential journalist and author, Bill McKibben dared to cross the bright red line separating journalism from activism. He understood that climate disruption is so existentially threatening that remaining a dispassionate observer was fundamentally immoral. While still penning a stream of influential books and articles, and managing an impressive academic career, in 2007, Bill launched Step It Up, a series of climate actions including calls for green jobs, which was a precursor to the Green New Deal.

The following year, he co-founded 350.org, the first planet-wide, grassroots climate movement. Its creative mobilization strategies have generated the most viral activist campaigns in history. It’s helped mobilize effective resistance to Keystone and many other oil pipelines. It helped launched the mushrooming fossil fuel divestment movement and produced the immense global Climate March.

Equally important, Bill has helped pave the way for the Gretas and the Xiuhtezcatl Martinezes, and the countless other young people who are the emerging global climate leaders who have come together as a generation in ways and at scales never seen before.

Bill is an improbable activist. His temperament is not that of a rabble rouser or an agitator. He’s the classically reasonable New England professor in the town square, a brilliant but rigorous restrained and acutely precise speaker and thinker, which is exactly why he’s so effective. He’s too honest, too earnest, too compassionate, too respectful, and way too knowledgeable to peddle simple ideologies or 50 simple ways to solve the climate crisis.

Bill first spoke here at Bioneers in 1996, and he’s returned many times since. It’s been an honor and joy to know him, and to witness and share his remarkable trajectory. He’s authentically modest, and probably uncomfortable with the attention and praise. A solitary stroll through his beloved Vermont woods is likely far more appealing, but Bill has a mission, and it’s our blessing that he does. Please join me in welcoming one of our living treasures who’s changing the political climate to create a very different kind of global warming, Bill McKibben. [APPLAUSE]

BILL MCKIBBEN:

Kenny, Nina, thank you for keeping this family going and growing for 30 years. This is the 30th birthday of Bioneers. That’s amazing.

And of course, as Kenny says, for me that’s a very resonant number because it was 30 years ago this month that I published The End of Nature, the first book about climate change. I was a young man at the time – 28. I’m an old man now. There are days when I feel old beyond my years.

One of the things that old people do is try and sort of keep a tally of how things went, try and sum up. I try not to do that. I try not to keep score. I try not to wake up in the morning and decide whether I’m optimistic or pessimistic, because I don’t see the point of it. It’s enough to get up in the morning and figure out how much trouble you can cause. [APPLAUSE] Still… Still, there are moments when some tallying is in order, and I’m going to do a little bit with you today, and it’ll be a little hard at first, and a little easier after that.

It’s hard not to keep score with climate change because the numbers are right there. We have a day-by-day account of how much carbon dioxide there is in the atmosphere from the monitors on the side of Mauna Loa. And we have a month-by-month account of how much the temperature is going up. The CO2 levels in the atmosphere are now higher than they’ve been for tens of millions of years. The temperature is higher than it’s ever been in human history. July was the hottest month ever recorded on planet Earth. Okay?

And the speed with which this has happened in remarkable. Thirty years ago, we were still issuing warnings about what was going to happen if we didn’t take action. Since we didn’t take action, we’re now issuing bulletins from the frontline every day. People here need no reminder of that. In Northern California, we literally shut down the power to millions of people last week in a kind of frantic effort to somehow keep large swathes of one of the richest places on Earth from catching fire.

Let me show you a couple pictures from a trip I organized last year up to Greenland, which of course is a stunningly beautiful place, the great storehouse of ice in our hemisphere, a place of just unmatched splendor. The ice sheet in many places is a couple of miles deep. It covers the biggest island on Earth. And of course it’s melting, and melting fast, and that’s hard to look at, hard to see. I don’t know whether you can make out that image or not. It’s a boat that sort of organized for the expedition, I’ll tell you about in a minute. As you can see out the front, there’s open water all around. I was standing behind the pilot and I was looking up at his electronic chart, and you perhaps can see the cursor that represents where the boat is is a couple of miles inland on solid land. I pointed this out with mild trepidation to the captain [LAUGHTER] and he laughed and said, “Oh, don’t worry, the chart’s five years old. Everything around here was frozen as far as you could see.” Five years ago. Okay? Not frozen anymore.

I was there because I had wanted to organize a way to get these two women up onto that ice sheet. The one on the left, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner, I think has been here in the past, and is a remarkable poet. One of the great poets in the world. She hails from the Marshall Islands in the South Pacific, one of the places that is literally…I mean, the highest point in the Archipelago is a meter above sea level, which is not a good place to be on a rapidly warming planet. She recruited the woman in black, Aka Niviana, a Greenland native, and together they performed this poem up on the ice that’s been seen by lots of millions of people up on YouTube.

I wanted them there because I wanted Kathy standing on the ice that when it melted would drown her home. And I wanted to try and drive home that, and she did a beautiful job. The poem is full of rage, as one would expect, but also of generosity and of an understanding that all the rest of us are following along this same trajectory.

Even for me, who spent as long as I have thinking about all this, it’s hard sometimes to imagine how fast it’s happening. [VIDEO PLAYING] I’m going to just show you a picture that I shot with my cellphone from the front of a helicopter as we were…as we were changing the batteries on one of these instruments that science has used to record the rescission of the glacier. It’ll take a minute to get to the good part as we kind of go over the fjords. Let me just use that time to say what we need always to remember is that climate change is by far the biggest thing that humans have ever done. It is our single biggest achievement, if that’s the word you want to use, as a species, to have fundamentally altered the chemistry of the atmosphere and with it the temperature of the planet, and with that the…with that to have altered every square meter of the Earth’s surface.

We’ve now lost 50% of the summer sea ice in the Arctic, in the last 30 years, in the time that we’ve been coming to Bioneers. Okay? The world, if you look at it from a satellite, looks entirely different than it did 30 years ago. People are supposed to get old over 30 years, but planets are not supposed to get old over 30 years, to change in that kind of way.

That sheet of ice at the snout of this glacier is 120 feet high, so a 12-story building. And just keep an eye—Just as we happen to be going over, this 12-story building just started letting loose. And those waves are 50, 60, 70 feet high. The pilot was a little trepidatious, but I encouraged him to circle once just to kind of…I wanted to…I wanted to watch this because it has a sinister beauty to it, like all things that happen on our planet, and because it is a reminder of what is going on every second, of every minute, of every hour, of every day on planet Earth, and every time that happens, the height of the ocean rises some tiny fraction of a millimeter and we’re a little closer into the New World that we are building with such stunning speed.

The Earth’s temperature has gone up about one degree Celsius. That’s been enough to cause an almost amazing change, a set of consequences. The oceans are 30% more acidic than they used to be. The world’s hydrological cycles are completely akimbo already. We’re seeing record drought [VIDEO ENDS] evaporation and drought, and hence setting the conditions for massive fires. Once that water is evaporated up into the atmosphere, it comes down, and so we see record flood. All the time, every day now, some place we’re setting new records and all of them grim.

The last year we recorded the highest reliably recorded temperatures on planet Earth. It got to 129 degrees Fahrenheit in a series of cities across the Asian subcontinent and the Middle East – 129 degrees. You can survive for a few hours, but after that, your body just can’t cool itself off. We’ve raised the temperature one degree so far. We’re on a trajectory at the moment to raise the temperature three degrees Celsius, five, six degrees Fahrenheit. If we do that, the scientists are very clear, it’s not hard to calculate, that that 129-degree temperatures will be common for weeks a year, across vast swathes of this country, much of India, the North China plain, on and on and on. Billions of people will not be able to live where they live. The UN estimates that if we allow this to happen, we can expect a billion climate refugees in the course of this century.

Look, a million refugees was enough to utterly discombobulate the politics of our country. Multiply it by a thousand and try to imagine the planet on which we’re living. Our job, the only job, for our time is to make sure that that does not happen, that the temperature does not go up any more than it has to go up.

There are some things that let us think it might be possible. The engineers have done their job as well as the politicians have done theirs badly. In the last 10 years, we’ve watched the price of a solar panel and a wind turbine just plummet. They cost a tenth of what they did a decade ago. And thanks to that gift, if we wanted to go to work, if we wanted to move at speed, we could. We’re in a position now to really move.

And we have a movement to help make that happen. A lot of that movement’s been born here in this place with people who have—I’ve been—just arrived and I’ve only been here a half an hour but I already saw Eriel Deranger and Clayton Thomas-Muller and Tom Goldtooth, and all sorts of people who built so much of this movement at the beginning. [APPLAUSE] I saw great prophetic voices like Terry Tempest Williams and Brooke already this morning, just people who have allowed us to understand the world.

When that movement began, it was small. It was indigenous people, it was climate scientists, it was faith communities, it was the sort of hardcore Bioneers people like that, but it has grown fast. We’re at the 10th anniversary this month of the first big day of global climate action when 350.org organized 5200 simultaneous demonstrations in 181 countries. That was great [APPLAUSE] but those demonstrations were small. There were 500 people here, and a thousand people there, and 10,000 people here. Now the demonstrations that we all organize are big. September 20th, this climate strike, saw seven million people in the streets around the world. [APPLAUSE] And so much credit to the young people who are sparking it, who are making it happen. [APPLAUSE] There is—

It’s been great fun to hang out with Greta Thunberg in the last month, but I’ve got to tell you, there are a thousand, 10,000 Gretas all over the planet, and they’re doing amazing work. [APPLAUSE] So that’s good. That’s good, but there is something mildly undignified about taking the biggest problem the world ever faced and assigning it to junior high school students to solve. [LAUGHTER] [APPLAUSE] So time for everybody else to step up their game.

So we have a crisis. We have a solution of sorts. There are many solutions, all the things that—But let’s use wind and sun as a kind of stand-in for all the thousands. We have solution. We have a crisis, we have a solution, we have a movement, and we have a foe. And let’s be very clear about that. We’ve learned a lot about—over the last 30 years, about what happens in this world when money and greed keep us from moving as we need to move. As Kenny said, we’ve learned from great investigative reporting that the big fossil fuel companies knew everything that there was to know about climate change in the 1980s, before I did. They knew everything. Exxon was the biggest company on Earth. It had a great staff of scientists. Its product was carbon. Of course it knew. We found now the documents in archives that demonstrate with uncanny accuracy that its scientists were predicting exactly what the temperature would be in 2019, and what the atmospheric concentration of CO2 would be, and they were spot on. Not only that, they were believed by the executives at Exxon. Every drilling rig that the company built they built higher to compensate for the rise in sea level they knew was coming.

What they did not do was tell the rest of us. Instead they invested billions of dollars in building this architecture of deceit and denial and disinformation. So that’s why it’s good that so many people have stood up, that so many people have gotten in the way of pipelines and frack wells and coal mines. We don’t win all those battles, but we win a lot of them. And even when we lose them, we slow down this onslaught. And every month that we slow it down is a month that the engineers drop the price of a solar panel another percent or two.

It’s very good news that people have tried to get in the way of their finances. The divestment campaign that so many people helped with. [APPLAUSE] We celebrated last month the moment when we went past the $11 trillion mark in endowments and portfolios that have divested from fossil fuel. [APPLAUSE] That was a good moment, but the really good moment was reading Shell’s annual report this year where they said that divestment had become a material risk to their business. Okay? [APPLAUSE] So…

So let me just, in the couple of minutes I’ve got left, just give you the shortest preview of what comes next. Okay?

There are two big centers of power in the world of politics and money. People are doing a great job trying to take on Washington. The young people at the Sunrise movement, many of them veterans of that divestment campaign who have formed the Green New Deal platform and are pushing hard for it, are doing enormous good work, and they need all of us behind them in what’s obviously going to be an election…with…forget it. [LAUGHTER] We’ve got to do what we’ve got to do in the next year, and there is no question about it, so we will do what we can.

The other center of power in this world is the financial world. We started down that path with divestment, but we are broadening that path. There are people like Eriel and Clay and others who’ve been working on the big banks for decades. Okay? But we’re all going to start working on them I hope now.

I had a piece in the New Yorker six weeks ago about the way the money they provide is the oxygen on which the fires of global warming burn. Okay? Chase bank, the biggest of them all, has lent $196 billion to the fossil fuel industry – these good numbers from Rainforest Action Network – over the last three years. They’re lending went up after the Paris Climate Accords. Every bad project you’ve ever heard of, they and CitiBank and Bank of America and Wells Fargo, all deep involved in. So that’s bad.

The good is we can fight them. Not everybody’s got a pipeline or a coal mine in their backyard to go fight, but you know what? Chase has conveniently located 5,000 branches across America in the highest traffic locations imaginable. Keep your eyes open for the signal about the day that we need you to be there. [APPLAUSE] Chase…Chase has passed out tens of millions of credit cards around the country. Probably there’s lots of people in this room who have one in their wallet. Everybody who has a Chase card also somewhere in their home has a pair of scissors and [LAUGHTER] we’re going to ask you to use them. [APPLAUSE]

We’re going to go figure out the ways to go at the absolute heart of global capital. It’s going to be a hell of a tough fight. It may be one of the kind of ultimate fights in this ongoing effort to salvage the planet. Stay tuned. [APPLAUSE]

I’ve given you the setup. I’ve given you the setup. I’m not going to tell you what the outcome of all this fight’s going to be. And the reason I’m not going to tell you is I do not know. This is a fight different from the fights that humans have been in before because it is a time test. If we do not win soon, we do not win.

Dr. King used to close speeches by saying, The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice. This may take a while, but we’re going to win. The arc of the physical universe is short, and it bends toward heat, and if we do not win soon, then we do not win. And by soon, I mean soon. There’s not going to be another 30 years before we know whether we did what we needed to do or not. In a much shorter time than that, in a time when everybody in this room is—with any luck will still be alive, we’re going to know whether or not we did what we needed to do when faced with the greatest challenge that human beings have ever been faced with.

I’m not going to tell you how it comes out, because I don’t know. I am going to tell you, because I’ve seen it for 30 years now in every corner of the planet and no place more than this corner, I am going to tell you that there is going to be a fight, and that fight is our fight, and it is such a privilege to just get to do it shoulder to shoulder with y’all. Thank you very much. [APPLAUSE] Thank you. Thank you. [APPLAUSE]

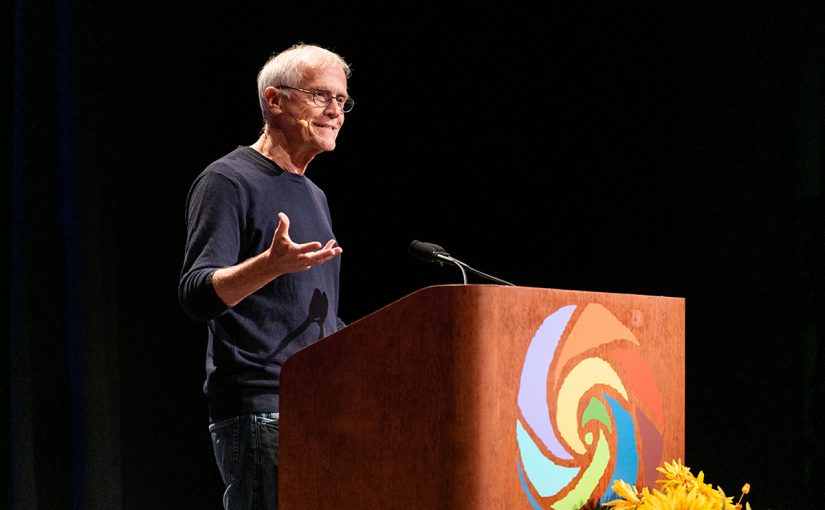

Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming | Paul Hawken

This keynote talk was given at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

The visionary goal of Project Drawdown, founded by Paul Hawken, is to actually reverse global warming by drawing carbon out of the atmosphere back down to pre-industrial levels. All the practices and technologies documented in Paul’s best-selling Drawdown book are already commonly available, economically viable, and scientifically valid. The true power of Drawdown is its holistic nature. Doing what’s right for the climate means doing the right thing across the board and will also create abundant, meaningful jobs and a vibrant green economy. For over 30 years, Paul has been at the forefront of transformative solutions for people and planet.

Paul Hawken, one of the most important environmental authors, activists, thinkers and entrepreneurs of our era, has dedicated his life to sustainability and changing the relationship between business and the environment. His many bestselling books include such massively influential texts as: The Next Economy; The Ecology of Commerce; Blessed Unrest; and most recently, Drawdown, The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming.

To learn more about Paul Hawken, visit his website. Find more information about Project Drawdown at drawdown.org.

Read the full verbatim transcript of this keynote talk below.

Transcript

Introduction by Kenny Ausubel, Bioneers CEO and founder

KENNY AUSUBEL:

So Paul Hawken truly needs very little introduction, but I’m going to make this minimalist because Paul asked that we show a short three-minute video that we constructed from a talk he gave here 10 or 15 years ago that is more visionary than ever. So we’re going to intro with that.

Paul first spoke here in ’94, and he doesn’t just see around corners, he somehow manages to find the wormholes in the space-time continuum that open up parallel worlds of possibility, that somehow soon start to migrate here onto Earth One.

He’s written a string of incredibly influential, really transformative books, from Ecology of Commerce; and Natural Capitalism with Amory and Hunter Lovins about the transformation of business, which is an agenda yet to fulfill, but the map is there; to of course Blessed Unrest, which chronicles Bioneers world, the rise of social movements and civil society all over the world to become the biggest movement in the history of the world, helped us to see ourselves more clearly; and then most recently, of course, he’s done Project Drawdown, which to me is the absolute North Star of goals and possibilities, and exactly where we need to be heading here.

Paul’s intention is to actually change the climate in a much better way, that’s conducive to life. So thank you, Paul, for dreaming up these parallel worlds of possibility that can liberate this world and help us see ourselves so clearly.

So we’ll show the video and then Paul will come on. Thank you so much.

[VIDEO PLAYING] [APPLAUSE]PAUL HAWKEN:

I want to ask you a couple of questions. The first question is: How many of you – just raise your hand – how many of you are freaked out about the climate crisis and climate change? Just raise your hand. Alright. Did anybody not raise their hand? I want to see. [LAUGHTER] Okay. Talk to me afterwards. I want to know what you know, because we obviously don’t, and that would be great. [LAUGHTER]

The other is: How many don’t believe in climate science or there’s anthropogenic climate science? Just raise your hand. [LAUGHTER] None this time. Actually it’s not meant to be a trick question, but it is. It’s like we all should have raised our hand because science is not a belief system. And it’s evidentiary. And that question or that dynamic was created by Frank Luntz and Karl Rove, and that—their intention was to make the people who were literate and understand the threat that climate change poses were believers, and that they were the rational people who don’t believe it. And it’s interesting because it’s the other way around. They are the true believers. They believe that the climatic stability of the Holocene period is going to persist for hundreds of years into the future, and there’s not one single shred of science to support that view. And so I’ll return to this in a minute later, but I mean, our languaging and how we talk to each other and about this is crucial and is critical.

The origin—I didn’t use slides today. If you come to the workshop this afternoon, lots of pretty pictures and things like that, so—And I’m also going to talk about my next book, which I won’t this morning. And I invite you to come to that. But this is really about Drawdown, the book and the project.

Its origin goes back to 2001, and it goes back to the same things that Valarie talked about. I mean, Bill talked about too, but 2001 was a strange year – 9/11 happened. And when 9/11 happened, I don’t know what happ—We all remember where we were, and after that, all’s I knew was that the world had completely changed. I didn’t know how it changed and where it was going to go and what was going to happen, but I had—was clueless. But I thought about what I was doing, and I realized that what am I going to do for the rest of my life. And I thought, I’m going to judge it by one question: Is it helpful? That’s all. I just wanted to be helpful.

There’s a definition of leadership which I love, which is leadership is actually the capacity and ability and desire to listen to all the voices, to hear and listen to all the voices. And I don’t know if I was or wasn’t then, or even I am now in some respects. I hope I am, but that is what I dedicated my life to do.

And at the same time in that year, the third assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change came out, and as every assessment has been before and since, each sequential assessment is more dire than the prior one. And that’s because it’s based on “consensus science.” There is no such thing as consensus science. Science is not a consensual process. You don’t watch your functional medicine guy talking to the allopathic guy, and saying let’s have a compromise here about your disease. I mean, you don’t compromise science. You may not agree. That’s different. But there’s no such thing. The consensus is being tamped down by the Saudis, by the Russians, by the Venezuelans, by the Chinese. We’re suppressing the science, and that was considered consensus science. Not at all.

And even then, though, it was dire enough, and I read the summary report, and I wanted to know a very simple thing, and I think all of us have that question, which is: Well, what to do. I get it. Science is fantastic. What to do?

And at that time, there came out that carbon mitigation initiative out of Princeton University with the stabilization wedges, the eight stabilization wedges that had 15 solutions. And everybody was sort of yeah! Good ole Princeton. Science. And I—Me too. I thought fantastic. Stabilization, wedges, whatever those are. But it sounded good. [LAUGHTER] And my grandmother made great pies. We thought of wedges too. [LAUGHTER] And apple, cherry, she—apricot pie was the best. But—And here are the stabilization pies, and… [LAUGHTER] and I looked at the solutions that basically infused them, and I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. And 11 of the 15 solutions could only be adopted by large multi-national corporations, eight of them being coal, gas and oil companies, nine being utility, 10 being a car company, and 11th being an appliance company. And there was only really one thing you could do, which was to drive less. And I thought, This is the solution?

And what was left out? What was left out was affordability. Every one of these things was deeply underwater financially, so these corporations were never going to do it. Second was left out was consumption, materialism, that was left out, not even discussed or addressed. Population was left out, completely. No one talked about population or how many or why. No discussion or the role of women, which [INAUDIBLE]. None. That’s been a hallmark of the climate movement is to pretend another gender doesn’t exist. And there was no discussion of agency, which is that, okay, this is what corporations can do, but what about individuals, what about cities, what about towns, what about farmers, what about community colleges, what about schools, what about buildings. I mean, you can go on and on, all the different levels of agency that we occupy as human beings.