A conversation with Gar Alperovitz, co-founder and co-chair of the Next System Project and the Democracy Collaborative.

BIONEERS: When you talk about the “Next System”, how far-reaching is the change you’re talking about?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: We’re talking about the entire political economic system, which means how business is organized, how cities are developed, how parliaments or governments are organized, how states are organized, how regions are organized. Everything, starting at the grassroots level in a neighborhood all the way up to: What’s wrong with the Constitution? What are the problems in parliaments? What are the problems in Washington? How do you replace the corporation? Every level. Changing the system means re-examining every single institution and seeing pathways forward, those that are theoretically meaningful but also practical things on the ground that point in a new direction.

I think as time goes on what we’re looking at is the introduction of new ideas. The ideas that became the New Deal were local experiments in the 1920s that were worked out and fine-tuned. Then when the time was right in the 1930s they went national with the New Deal, we saw Medicare, Social Security, and labor law allowing for unions. All that was experimented with locally, then became national, and I think we’re going to see a similar process.

BIONEERS: Do you feel there are certain big, game-changing actions that would address many of those things at once?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: People usually distinguish between reforms, which are small changes at the edge, and revolutions, where everything changes at once. The language I like is “evolutionary reconstruction”. This means redeveloping how cities are organized, piece by piece, looking at how regions might be changed and developing the elements, walking the path as you go. It produces systemic change, fundamental change in the institutions, but the pathway is a reconstructed pathway, not reform. Reform keeps the institutions in place and tries to fix up around the edges. Revolution is explosions, tries to throw things over. The pathway we think makes sense in an advanced system like our own is kind of evolutionary, while changing the fundamental institutions as you go.

BIONEERS: A key question is how to deal with industry, transnational corporations and large banks that hold so much power?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: I think we will begin to see larger scale publicly-owned or democratically owned structures, maybe even regional/community/worker, different structural forms that represent the community that are not just centralized kind of authorities.

A decade ago, the big banks collapsed, General Motors collapsed, Chrysler collapsed, and the U.S. government nationalized those companies. If the speculation had been allowed to go on, the country would have gone into massive depression. When General Motors and Chrysler went down, all the suppliers in the cities around them suffered too, which meant those communities were badly beaten up. That’s why the Obama administration had to jump in and do something. Then, after we put a lot of taxpayer money into them, they went back to the old owners after taxpayer expense.

I think we’ll see another economic crisis, because the regulatory structure is being ripped apart by the government at the interests of the big corporations and banks. At some point, some of those will become public or regional or state structures.

BIONEERS: What are public or community banks, and how do they fit into the picture?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: Big banks in almost every other major country around the world are actually public banks. It’s very common for the reasons I’m talking about, because if you don’t do that, you run into trouble and it costs the whole country a lot of money.

The most important aspect is that this is where people put their savings, but also city tax money goes into the public bank. Cities have a lot of taxpayer money, so why put it in a big, big New York or Wall Street bank, which invests that capital in speculative things, rather than the local community? Keeping that money in public banks allows that capital to be invested in what a community needs. It’s part of this whole notion of democratic development of the community. It’s a very practical, common sense approach, and not in any sense radical.

We love to point to the Bank of North Dakota because they do it so well. The Bank of North Dakota is a statewide public bank that’s 100 years old, and it’s in one of the most conservative states in the country. They run it with the support of farmer co-ops and small businesses, local townspeople. It’s very popular and very successful.

The model is being replicated or considered in many parts of the country, including Los Angeles, Washington State, Philadelphia, and Phil Murphy won the governorship of New Jersey campaigning on developing a public bank. Cleveland hasn’t done it yet, but is in the process.

BIONEERS: You’ve mentioned that Ohio has quite a lot of action in this regard. Can you describe what is happening there?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: Ohio is very interesting because we’ve had a lot of job displacement and companies leaving. We can trace this all the way back to the Youngstown fight, which was about 35 years ago, when a big steel company shut down and workers decided to take it over and own it themselves. There was a big, big fight about that. Since then, the idea has been in the air that companies might be owned by workers, or in that case, by the community or community-worker ownership.

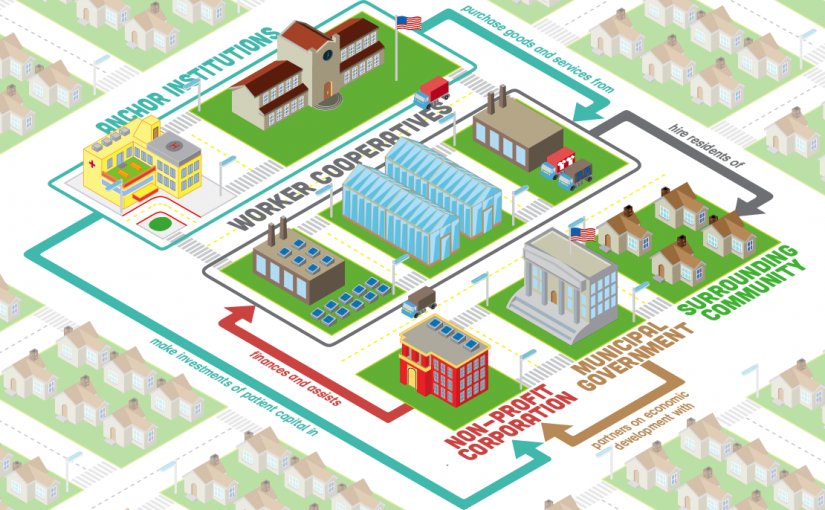

Many worker-owned companies have developed over the last number of years. ESOPS – Employee Stock Ownership Plans and co-ops in Cleveland culminated with a development of about 40,000 people in a very poor, black neighborhood with about $20,000 per year annual family income, and 20% unemployment. Our folks helped to develop a community-wide nonprofit corporation that covers the whole community, and worker-owned companies are attached to that. They’re not stand-alone, they’re part of the community building structure.

BIONEERS: How do worker-owned companies benefit the community and build community wealth?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: A worker-owned company is a worker-owned co-op, one person, one vote. One example would be a credit union. There are 3 million people in credit unions, so this is very conventional in many parts of the country. The idea that the workers could have a stake in their company and own it, control it, is just an extension of this. There are lots of co-ops in this country, and a lot of experience with this around the world, so it’s not a very novel idea.

What’s interesting is bringing co-ops in as part of a community structure that is a nonprofit corporation. This benefits the whole community, because those companies can’t get up and go. They’re financed in part by the community through a community corporation. So it’s a mixed model, and that’s what’s unique about the Cleveland model and others in different parts of the country that are following suit.

The notion of trying to stabilize the economic health of communities is very commonsensical, and doing it in ways that change the ownership patterns. Community and worker-owned companies don’t get up and move, because they live there and the people are there.

BIONEERS: You stress the importance of “anchor institutions” in this next system. What are those?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: Big anchor institutions are very important. They are institutions that don’t leave the area. In Cleveland, we have both public and private hospitals as part of the network. Cleveland Clinic is a private hospital. Case Western Reserve University also has a hospital and medical school. Hospitals connected with universities are all anchored in the community. They receive and use so much public money – Medicare, Medicaid, educational money – you can use that as leverage in the development process.

There’s a whole network called the Health Anchor Network, and those anchor institutions help build up the community by redirecting their purchasing power. They say, we buy a lot of food, we buy a lot of goods, we buy a lot of furniture, we buy a lot of equipment. If we direct some of that to the community – not just to get supply, not just because it helps the community, not just because it might be good to give the workers some ownership, and not because it’ll anchor more jobs – but it also improves the job situation in a community, and the health outcomes improve. So this is a converging trend.

Anchoring institutions in a way that allows people to have a long-term stake in the community is financially practical and it makes sense to people. The ideas seem novel, but they’re quite, quite straightforward.

BIONEERS: Where are some other places where innovative projects in this vein are sprouting up?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: Austin, Texas and Madison, Wisconsin are doing really interesting things with co-ops and land trusts and credit unions. There are people in Oakland and the greater Bay Area doing really interesting development around transit exits. When you put in a subway or a transit system at the exits, property values go way up, because it’s a really good place to put housing. Developers want to capture that, but if you hold on to it and develop it in public ways, the public captures that money and can subsidize the transportation system. Washington, D.C, has been doing that for a long time.

Major cities like New York City, Philadelphia, Seattle are all experimenting with worker-owned land trusts, different kinds of end-to-end energy systems.

The truth is lots of people are taking part in what some people are calling The New Economy Movement. If you go to the Democracy Collaborative website and many others, you’ll find hundreds of these kinds of experiments. There’s enough practical experience around the country, you can just call somebody up and find out how to do it.

Several of our folks have gone to the city of Preston in England to share what is happening in Cleveland. It’s a city of about 120,000. One particular person there, Matthew Brown (who’s now the head of the city council, but at the time he was what we would call an alderman) got turned on with what we were doing at the Democracy Collaborative and with what was going on in Cleveland, and got interested in one of my books. He said, We could do that here in Preston. And he rolled up his sleeves and got it going. People liked the idea. Other cities in England are looking at doing that kind of model. The Labor Party has picked it up, and there are a number of people working in European communities that have begun thinking about it. You don’t have to have an election, you can develop it locally. It’s a very exciting development.

BIONEERS: What about rural areas where small communities have been abandoned by poor agricultural policy choices and big corporations? There was an intentional effort by industry and the US Government to get rid of farmers, mechanize agriculture and capture all that land to turn food into a commodity. Now these small towns are really suffering.

GAR ALPEROVITZ: Yes, it’s terrible history. There are a very small number of farmers now, about 1.5% of the labor force. That means the people either stay in these dying towns or they drain to the cities. Development in rural areas is very, very difficult. Some of that can be reversed around small town redevelopment in rural areas, and I think some of it’s going to be. Historically, farmers co-ops and rural electric co-ops organized and played a big part in putting together the Bank of North Dakota.

Also, with adequate political buildup, it makes every bit of sense to create land trusts from the point of view of the nation, to keep people on the land and in small towns. Small towns can be very ecologically efficient if you build them up sufficiently. I’m looking for current experiments that work in the rural areas. There are some attempts in Wisconsin to create multi-stakeholder kind of cooperatives, often around using a public facility or public university.

You put your finger on one of the hardest problems in the rural, decaying areas. The paradox here is that subsidies for agriculture are a huge part of the federal budget, and yet farmers are a very small part of the population. Somehow the politics of that can be worked. It’s a really hard problem. It’s doable, but it takes a political push. We’ve got to organize the constituency.

BIONEERS: How do politics play into these new economic models and systemic changes?

GAR ALPEROVITZ: Red/Green/Blue doesn’t work anymore. Ohio is a good example. Ohio voted for Mr. Trump, and it is one of the most interesting places for experimentation in the country. So what’s happening at the grassroots level may be different from what happens at the current level of politics.

What’s driving a lot of our current politics is unanswered pain, and it’s being exploited by the right. But the pain levels are growing, and that means you need solutions at some point. I think we’re seeing the prehistory of a real transformation happening. If you look at it historically, the kinds of things people are focusing on that look like small experiments are often the seedlings for giant redwood trees. That’s possible. It’s also possible that we will go in a really rightwing direction and things get very painful. Lots of transformations go through difficult phases.

At the Next System Project, we’ve asked the big questions: How would you actually design a system? We’re talking about bits and pieces here. There’s a whole group of people who we’ve asked, “What makes sense? How do you get democracy? How do you get real liberty? How do you get equality? How do you get ecological sustainability? What is a systemic vision? We’ve had something like 45 different contending papers written. We’ve had conferences at MIT and Harvard, really trying to get deep into this so-called “Architecture of the Next System.”

Ideas matter, and have magical power because people see, “Oh, we could do it a different way. If we really wanted to, we could roll up our sleeves and try it here.” That’s what makes this period a very powerful time of American history.