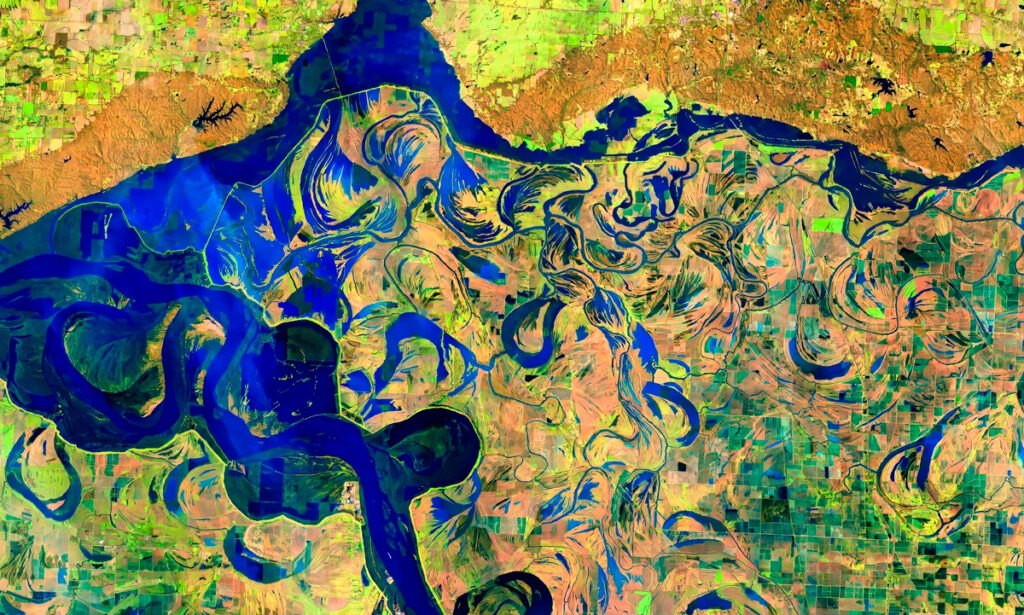

In 1999, three land rights defenders were kidnapped after they left Indigenous U’wa territory in Colombia. Multinational oil interests seeking the massive reserves beneath the region were attacking U’wa lifeways — and those who accompanied them in resistance. The bodies of Terence Freitas, Ingrid Washinawatok El-Issa (Menominee) and Lahe’ena’e Gay (Hawaiian) were eventually found bound and bullet-riddled in a cow pasture. The murders were part of a struggle that would continue for decades, bringing about both setbacks and victories for the U’wa.

Twenty years after the murders, Terence’s partner, Abby Reyes, finds herself a party in Case 001 of Colombia’s truth and recognition process, which is investigating the causes and consequences of Colombia’s internal armed conflict. After years without answers, they want to know her questions about what happened, her “truth demands.” In “Truth Demands: A Memoir of Murder, Oil Wars, and the Rise of Climate Justice,” Reyes confronts these questions, navigating her own grief and the fight for accountability for the murders of Terence and his colleagues. In the below conversation, Reyes, a lawyer, environmental organizer and Director of Community Resilience Projects at University of California, Irvine, discusses land rights advocacy, entrenched oil interests, resistance and resilience, and what she hopes her book offers climate activists. For a deeper look, read this moving excerpt from “Truth Demands.”

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Bioneers: The book chronicles your personal journey of grief and environmental organizing in the wake of the murders of Terence and his colleagues. What moved you to write this story now, and what do you hope it offers to emerging climate activists?

Abby Reyes: To me, their murders were a harbinger of the climate chaos that we are grappling with now. At the same time, the way they lived their lives set an example that helped usher in the rise of climate justice. The land rights defenders who were killed with Terence were beloved native North American women leaders who were ahead of their time. Lahe’ena’e Gay, from Hawai’i, was a traditional Indigenous knowledge educator and educational systems designer, and Ingrid Washinawatok was a Menominee leader from Wisconsin who was key to what eventually, after her death, became the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The rights the U’wa community asserted before their deaths and have continued to advocate for at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights draw on this United Nations declaration that Ingrid worked tirelessly to put in place.

“I wrote with the hope that the practices that helped me come back home to my body and voice might help others as we navigate the climate disasters already underway, do all we can to prevent further harm, and work together to build the climate future we know is still possible.”

I came into adulthood through the gates of these murders, with this paradox lodged in my throat, and I needed to clear my throat. Writing was one way that I did that. It’s this very specific story, yes, but it’s also a universal one — about how we navigate grief and the efforts we make to reestablish connection with the people, animals, plants and minerals that make up this earth. Above all, it’s a story about the power of collective action. I wrote with the hope that the practices that helped me come back home to my body and voice might help others as we navigate the climate disasters already underway, do all we can to prevent further harm, and work together to build the climate future we know is still possible.

These murders took place near U’wa land, a known mother load of oil in that country. It’s a place where oil pipelines have always been a magnet for armed violence. When the internal armed conflict in Colombia shifted and the country entered a transitional justice process, I was invited, along with Terence’s mom and the families of the others who were killed, to be recognized as victims in Case 001 of the Truth and Recognition process. Terence’s mom and I opted in. The first requests from this tribunal included: What are your stories? What questions have you been holding about what happened? What do you want to see happen now? The requests felt enormous to me, and they felt impossible. For decades, figuring out how to live in the world in relation to these unanswered questions was a feat of survival. So having these questions presented to me again in earnest took a reorganization of my relationship to the events.

What I knew to be true was that for me to be able to move through this process, I needed witness of what was happening. I wrote in order to have that witness. That’s why the timeline is now. But what emerged, unexpectedly, was that some of the legal claims the community had filed at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, even before the murders, began to move forward. After years of dormancy, we worked underground to create the conditions for emerging U’wa leaders to pick up the baton and carry it to victory, which came about just a few months ago. So the timing also feels right to share my part of this story, because it is important for all of us, globally, to draw inspiration from the U’wa community’s recent victory. This victory establishes Colombia’s accountability for human rights violations against the U’wa people and sets the stage for strengthened protections of Indigenous peoples across Latin America. We need those victories now.

Bioneers: Land rights advocacy has only gotten more dangerous in recent years. What do you believe needs to shift—politically, legally, or within movements themselves—to better protect those doing this work?

Reyes: It is way worse than when I was a young person starting out in the rural southern Philippines. In the mid-90s, my mentors, Jesuit lawyers who were working in the countryside, were already facing lethal threats to their personal safety. But what was merely anecdotal then is very well documented now. Structurally, the answers are what you would expect from me: demilitarize and uncouple our militarization from our dead-end commitment to fossil fuel extraction.

The other shift that we’re seeing more is a move toward operationalizing our commitment to taking cues from grassroots leaders. We need to follow the leaders of Indigenous, Brown and Black communities who are closest to the harms, because the solutions are there. When we combine the wisdom and lived experience of the frontlines with the brawn and resources of allies who are in right relationship, we have a chance at using the dominant culture’s forums — legal, cultural or structural — to embed frontline vision, principles, stories, and strategies into more mainstream forums (where, in our current systems, decisions are largely still made). We have a chance at it — if we can figure out how to listen in a way that is operationalized.

“Social movements aren’t just banners and narratives; they’re made up of people, and those people must seek right relationship.”

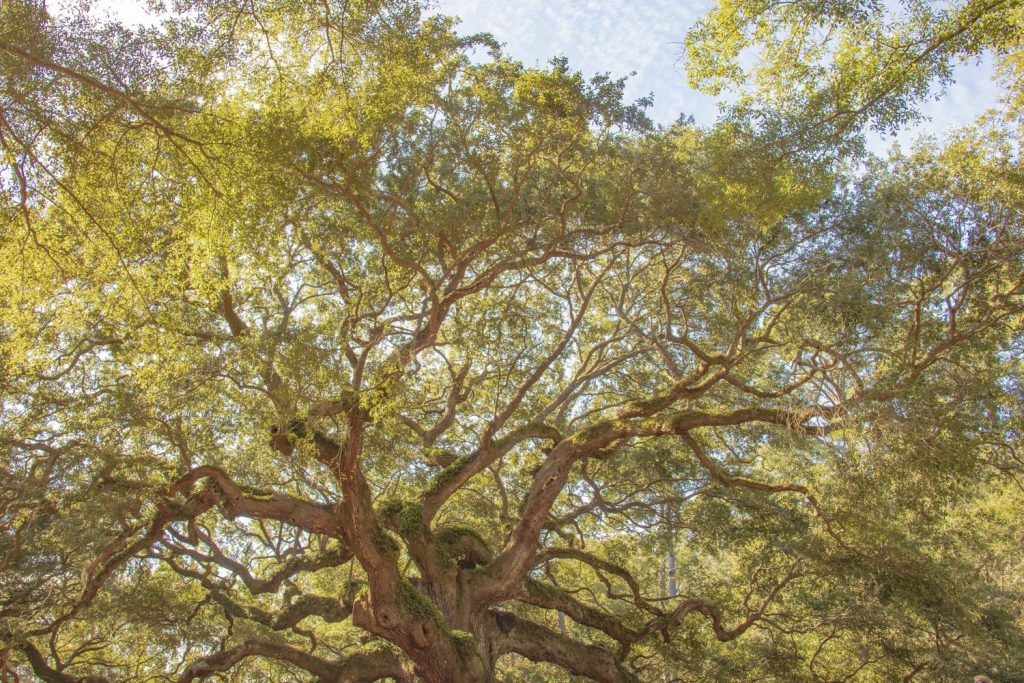

Pueblo U’wa offers a good example of long-term accompaniment, which looks like decades of support from people across society in response to the Pueblo’s requests. At the social-movement level, people need real relationships with each other across organizations and frontline communities. Social movements aren’t just banners and narratives; they’re made up of people, and those people must seek right relationship. Growing into right relationship depends on our ability to hold both the past and the future while being rooted in the present. Moving backwards, there are often measures of repair, accountability and reset that need to be made. It also means looking laterally and forward in a way that lets us stand in our interdependence. It’s never been a case of helping. It’s always been the case of mutual liberation.

Bioneers: Environmentalists have spent the last 25 years struggling to deal with super entrenched oil interests, and that struggle has only become more heightened recently as political winds have shifted. What can the environmental movement do, strategically and tactically, as political momentum favors oil and gas development?

Reyes: This is happening in our political discourse as we speak. Yet there are indications that our legal systems are currently holding — against all odds and despite the shock that our democratic institutions could be pushed this far. I would answer your question in part by pointing to the need to hold carbon majors accountable for climate damages. Those are strategies that have been tried in forums all over the world for the last 15 years or so, with varying degrees of success in moving forward judicial analysis and procedure.

“So even in this moment where use of the courts feels like a weak muscle, we know it is a muscle that strengthens with use.”

Just recently, scientists from Dartmouth published an article in Nature illustrating the trillions in economic losses attributable to the extreme heat caused by emissions from individual carbon major companies. In many cases, it has been challenging to convince courts that we could crack that nut. Courts might say, How could you tell if one company was responsible for emissions in Boulder, Colorado, versus Vanuatu? Therefore, the liability has seemed obscure and unattainable. Now, the premier scientific publication has said, “Wait, wait, wait, that’s actually not true, and here’s how we do it scientifically.” So even in this moment where use of the courts feels like a weak muscle, we know it is a muscle that strengthens with use. Right now, we are seeing scholars and scientists be more willing to be in right relationship with cities, counties, states and communities that have been asking the bar to take action.

Bioneers: You’ve worked across continents and contexts — from rural Philippines to Colombia to California. What threads of resistance or resilience have felt universal across those places?

Reyes: One common thread that stands out is that communities know what they need. Communities are living the consequences of our dominant economic system, and disinvested communities know that the solutions to environmental mitigation or adaptation issues are linked to economic justice and building the human infrastructure for deep democracy. These solutions cannot be untied from each other. Over time and across geographies, I’ve also seen disenfranchised communities call for those walking alongside them to put bodies on the line.

In the U’wa territory, for example, especially in the period immediately following the 1999 murders, the violence against the community by public and other forces was acute, armed and lethal. That action was in response to the U’wa people literally placing their bodies on the road to block Occidental Petroleum trucks from reaching a sacred site where the company wanted to drill another exploratory well. The call for bodies on the line was well received in the countryside in that period. Indigenous folks were joined by non-Indigenous farmers, students, clergy, legal witnesses, and others. And it mattered — it deterred the violence for some duration. So when we’re working with communities where we need remedies beyond legal and policy intervention because those methods aren’t working fast enough to prevent harm, there are also these “meta-legal remedies,” as my mentors in the Philippines would call them.

“Building the new can feel removed from the struggle, but it is every bit as much a practice of bodies on the line.”

A thread of resistance that feels universal is that work is often happening not only to block the bad in all the ways that we just said, but also to build the new. Building the new systems, structures, and cultures we need is a significant part of the social movement framework often called Just Transition. Building the new can feel removed from the struggle, but it is every bit as much a practice of bodies on the line. In the communities I work with here in California, in particular the Mexican majority city of Santa Ana, building the new looks like worker-owned cooperatives, community land trusts, regenerative agriculture, cleaning the soil, and mutual aid infrastructure to face climate disaster and achieve health equity.

In places where it has long been clear that the dominant systems weren’t set up to facilitate thriving for all, communities are looking to each other and themselves to create community owned systems of regeneration, resilience and interdependence. That, too, is a form of bodies on the line — one that excites me because it gives us something to rally around.

Bioneers: In your view, what would a truly just legal framework for climate resilience look like?

Reyes: There are community stewards across the country pioneering and articulating practices of community-driven climate resilience planning and action. Many of those stewards are organized into the National Association of Climate Resilience Planners. The association started out in part as a way for community stewards to assert their place at the table when local governments, whose hands were often forced, realized the need for environmental justice analyses in climate planning. When governments hire consultants to talk to the community, these community stewards were saying, “Hey, we’re right here, and we’ll help you shift.” Now many community stewards have turned more directly to creating the “just enough” infrastructure needed for community ownership and sacred governance for the whole.

Supporting these forms of deeper public participation requires all sorts of legal apparatus. And that lawyering is happening. We created the Just Transition Lawyering Institute in recognition of the skilling up that lawyers everywhere, especially lawyers serving Brown, Black and Indigenous communities, are doing right now to meet this need. It’s an enormous question. Even just this one slice requires transformations at every level. But it’s an instructive lens that reveals the road maps that are right in front of us for where we need to go.