As co-leaders of a global alliance working at the intersection of gender justice and environmental resilience, award-winning, groundbreaking activists and visionaries Amira Diamond, Melinda Kramer and Kahea Pacheco explore the transformative power of grassroots women’s leadership in confronting our most pressing ecological challenges. By sharing stories from their global network, they illustrate how frontline women leaders are implementing community-based solutions that protect land, water, and biodiversity as well as advancing climate resilience across diverse regions. They also delve into WEA’s unique co-directorship model—a shared leadership structure that embodies collaboration, collective visioning, and sustained impact in alliance-building work.

This talk was delivered at the 2025 Bioneers Conference.

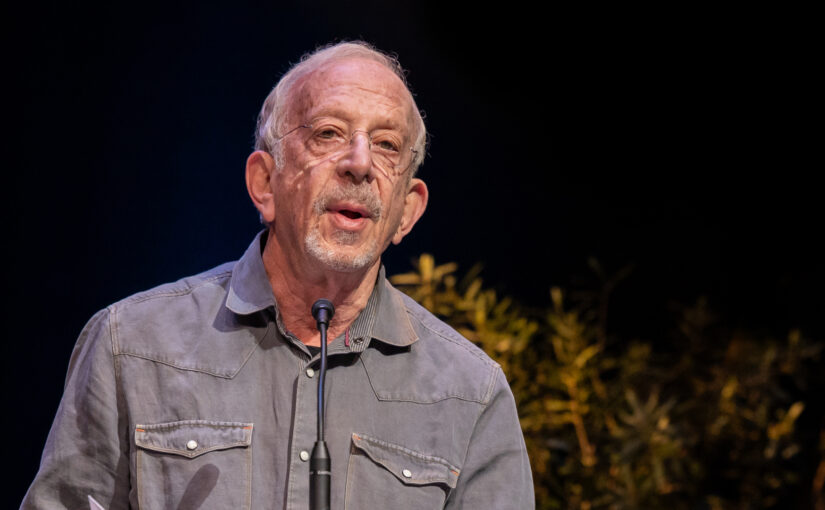

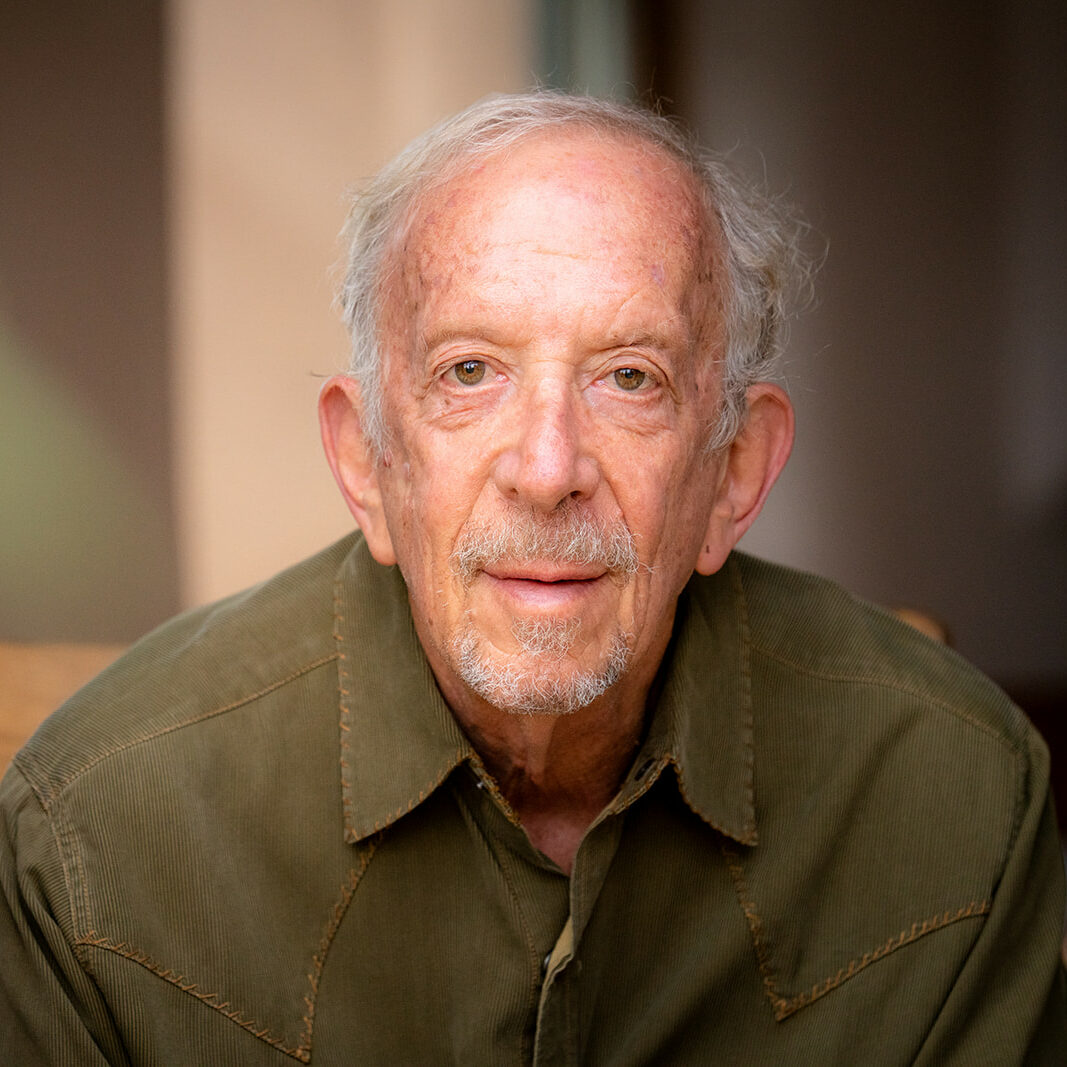

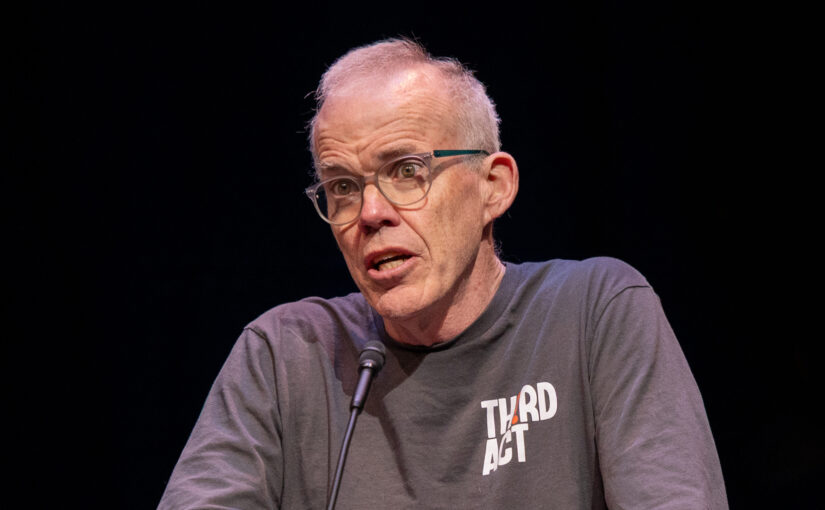

Amira Diamond, co-founder and Co-Executive Director of the Women’s Earth Alliance (WEA), where she collaborates with frontline communities, global NGOs, investors, and philanthropists to implement environmental programs focused on nature-based solutions, clean energy, advocacy campaigns, replicable models, resilient communities and justice across environmental, health, and LGBTQ rights, is a seasoned social entrepreneur with over two decades’ experience designing and leading rights-based programs at the intersection of climate solutions, gender equity, and economic development. Previously, she served as the West Coast Director of Democracy Matters and directed organizations such as Julia Butterfly Hill’s Circle of Life.

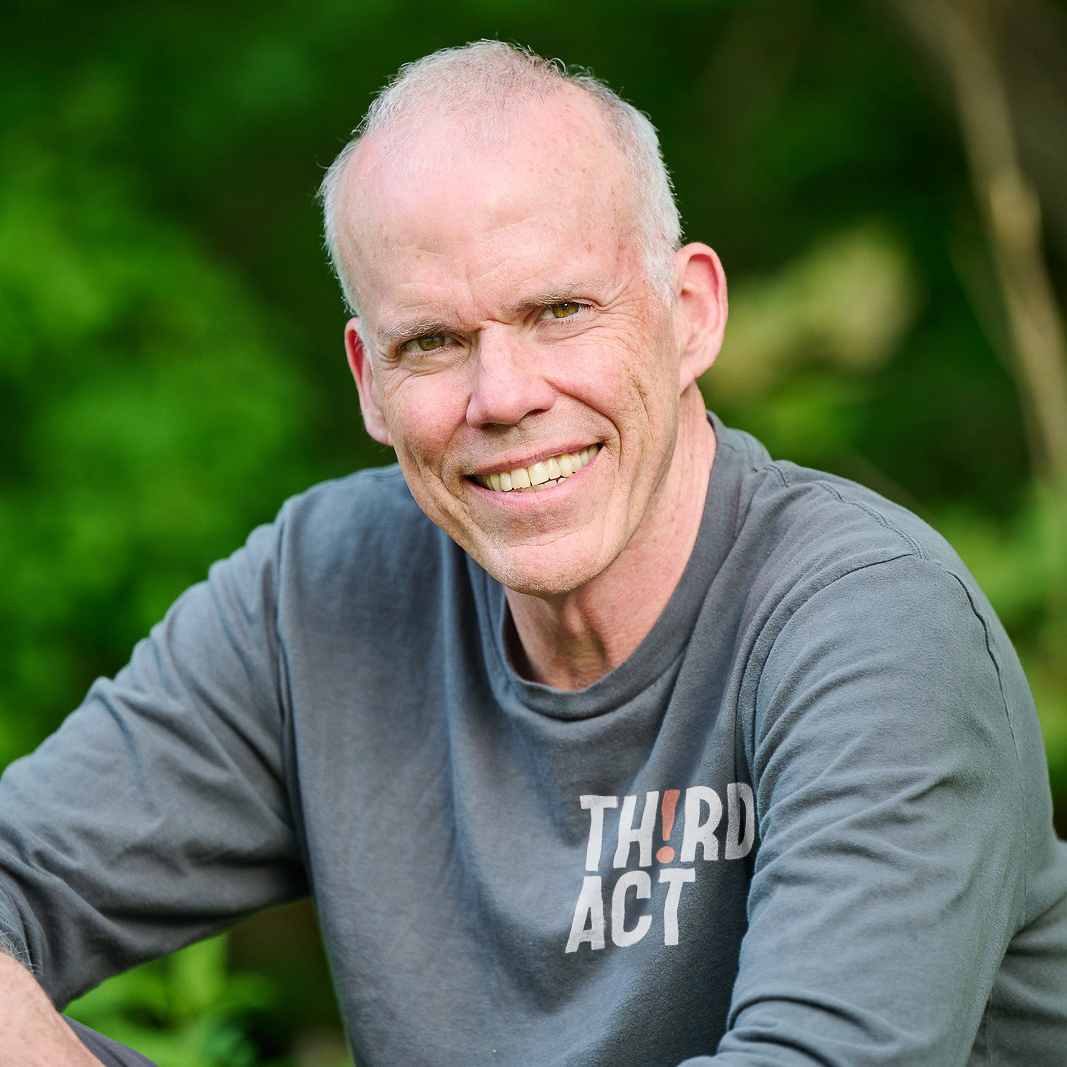

Melinda Kramer, co-founder (in 2006) and Co-Executive Director of the Women’s Earth Alliance (inspired by the resilience of women in impacted communities around the world and the desire to bridge the resource gap for these frontline women tackling urgent climate challenges), is a passionate advocate for social justice, the environment, and women’s rights. An environmentalist and cultural anthropologist, she has worked globally, learning from grassroots leaders on the frontlines of environmental crises. Her career has spanned sustainable agriculture work in Kenya with CARE International, capacity-building initiatives in the North Pacific Rim with Pacific Environment, and co-founding the Global Women’s Water Initiative.

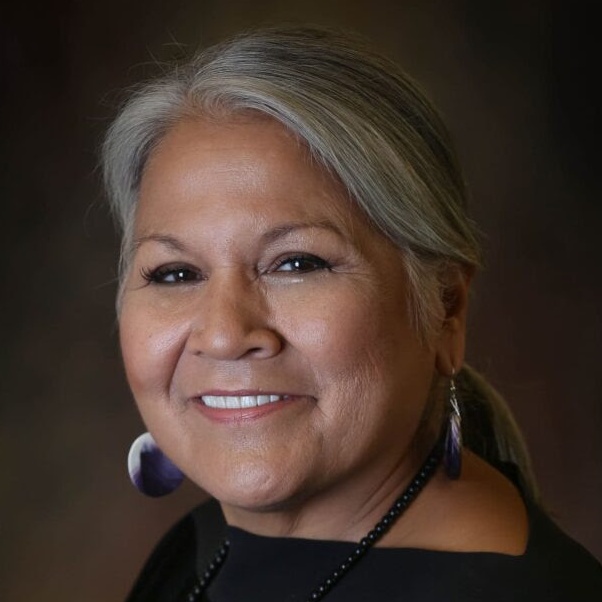

Kahea Pacheco (Kanaka ’Ōiwi), Co-Executive Director of the Women’s Earth Alliance (WEA), is a passionate advocate for Indigenous people’s rights and climate justice that puts aloha ʻāina at the heart of solutions. She joined WEA in 2011 after receiving her law degree with a focus on Environmental and Federal Indian Law. With WEA, Kahea has facilitated legal advocacy partnerships for Indigenous women-led environmental campaigns and co-led the development of the “Violence on the Land, Violence on our Bodies” initiative. She also serves on the Advisory Councils for the World Economic Forum’s 1t.org and Daughters for Earth.

EXPLORE MORE

Woven Liberation: How Women-Led Revolutions Will Shape Our Future

Read an edited and excerpted version of a panel discussion held at the 2023 Bioneers Conference with Azita Ardakani, Zainab Salbi, and Nina Simons.

Zainab Salbi – Daughters for Earth

In this Bioneers 2022 keynote address, Zainab Salbi, a co-founder of Daughters for Earth, explores the interconnection between our personal search for healing and how we face the challenges of climate change.