This keynote talk was delivered at the 2019 Bioneers Conference.

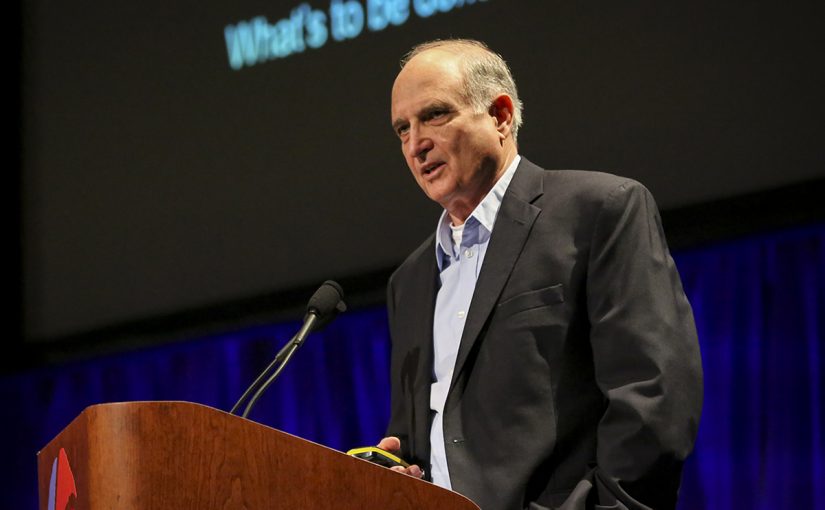

We are living through the most dangerous challenge to free government in the U.S. anyone of us alive has encountered. Like a house with crumbling foundations, American democracy is suffering from decades of deferred maintenance. The challenge of repairing and updating our institutions would be difficult enough, but we obviously do not live in “normal times.” The pace of change is faster, threats bigger, risks global, and the time to forestall the worst is very short. David Orr, one of the nation’s most lucid and influential thought leaders, draws from his forthcoming book, Democracy Unchained: Politics as if All People Matter, to consider what we must do to return to the better angels of our collective nature and turn the ship around. What happens next is up to us.

David W. Orr, a Professor of Environmental Studies & Politics (Emeritus) at Oberlin College, is a pioneering, award-winning thought leader in the fields of Sustainability and Ecological Literacy. The author and co-author of countless articles and papers and several seminal books, including, most recently, Dangerous Years: Climate Change, the Long Emergency, and the Way Forward, he has served as a board member or adviser to many foundations and organizations (including Bioneers!). His current work is on the state of our democracy.

For more information about David Orr, visit The Oberlin Project.

Read the full verbatim transcript of this keynote talk below.

Transcript

Introduction by Kenny Ausubel, Bioneers CEO and founder.

KENNY AUSUBEL:

For decades, the work of David Orr has revolved around changing the structure of a system that’s programmed for disaster. I’d like to introduce David through some of his own words excerpted from his forward to my last book, Dreaming the Future. David is an amazing writer.

Structural change requires tossing overboard many of the foundational myths of the modern world. There’s the myth of lordly human dominance over nature that presumes that we know enough to manage the planet even though we can’t manage the back 40. There’s the myth that ignorance is a solvable problem, not an inescapable part of the human condition. There’s the myth that economy can grow forever on a finite planet. And it’s corollary, that human happiness is a byproduct of consumption, a word that ironically once referred to a fatal disease. [LAUGHTER] There’s the myth that–[LAUGHTER] [APPLAUSE] Yay, David. There’s the myth that security is the offspring of a monstrous capacity to kill and cause havoc. Beneath such thinking is a kind of feckless belief that we can tame the demons that we unleash on the world.

And he continues: Two broad revolutions have been gathering force for centuries, but always against long odds and stacked decks. In the West, the first began with fledgling steps toward democracy and the concept of human rights based in law. Across the span of nearly 2500 years, the battle for basic rights has gathered force. The decks are still stacked, and the road ahead will be no less challenging or bloody than that already traveled, but the battle for enforceable human rights and the extension of the rights to life, liberty and property to future generations and eventually the extension of rights to animals and nature will go forward. And someday, what Martin Luther King, Jr. described as the arc of history, will indeed bend toward inclusive and dependable justice.

The second stream is still older. It’s the knowledge of how to make the human presence in the world on nature’s terms not just human contrivance. Everywhere its hallmark is the humility to learn from nature and develop partnerships with ecological processes. It’s alive and flourishing in our time in the work of so many people and the Bioneers all working with nature and posterity in mind.

David Orr’s vision, wisdom and example have helped shape and guide so very many of us for so many years. Although David’s above all an educator, he’s always combined scholarship with action. Along with an illustrious academic career, his teaching has extended far beyond the classroom into the campus, the town and region around it, and the national dialogue. He’s been seminal in advancing ecological literacy and the greening of educational curricula in higher education institutions. His books remain foundation to the entire field.

He’s also been a leading figure in developing ecological design and putting it into action in local economy movements. A long-time professor of environmental studies and politics in Oberlin College, in 1996, he spearheaded the design and construction of the first LEED platinum green building on a US campus. [CHEERS] Yeah. [APPLAUSE] The Oberlin project then extended the effort into a Town Gown partnership to build a regional green economy template that others are now emulating.

David’s influence has also reached into the corridors of national political power. He was in the vanguard of identifying climate disruption as the biggest political failure in human history. In 1989, he organized the first ever conference on the effects of climate disruption on the banking industry. In 2008, he organized the Presidential Climate Action project with a world—which was a world class think-and-do tank that positioned climate disruption as the top national security issue. Its policies and recommendations penetrated the Obama administration’s policies, though we wish it had been more.

His books including Down to the Wire: Confronting Climate Collapse are among the best on the subject. David’s received countless prestigious awards and sat on many, many nonprofit boards and foundation boards including Bioneers and Rocky Mountain Institute. His focus today, thankfully, is on the crisis of democracy and on the crisis of governance that threatens the viability of human civilization.

So please join me in welcoming our dear friend, who reminds us that hope is a verb with its sleeves rolled up, David Orr. [APPLAUSE]

DAVID ORR:

Pronouns are interesting things, and they cause us to do lots of things we otherwise would not do. So when we say I and me and mine, that takes us to markets. That’s the side of us that is a consumer. If you say we, ours, and us, that takes you to a different area, where we’re citizens, not just of the United States, but also of a biosphere, and a moralsphere. So for 40 years or longer, we’ve had a war waged against ours and us and we, a war waged against government. Get government off our backs. Government messes up everything. So government is the problem. Markets are said to be infallible.

Now the point of what I want to say today is that this is the most massive political failure in history. We call it climate change or climate destabilization, but it is chaos in any word. So I want to connect that to a political failure, this failure to do the public business in a way that was transparent and open and competent. And that’s the headlines every day.

And so we had the first warning given to a US president about climate change. It was given in 1965. That’s a long time ago. We knew enough in 1965 to develop a day jury, a climate policy binding in law.

So let’s talk about politics. You’re not supposed to talk about politics, sex and religion, and I’m going to talk about politics. We’ll leave sex and religion out of this. Unless you…nevermind, that’s too…[LAUGHTER]

Now, here’s the origin of the idea. Lost in the mists of time, we don’t know exactly where the idea of democracy started, but in the Western world it started here. That is the agora or the Greek forum below the Parthenon. This is where Socrates and others debated the ideas of democracy, and it wasn’t always pretty. Democracy seldom is. But what they did was to wager a bet that enough people, enough of the time, would know enough and care enough to conduct a public business in a way that was responsible.

And then there was a second proposition, and the second proposition was very simply that you and I matter, that people matter, our rights count. As Jefferson put it, unalienable rights that we have to life and certain things that guarantee our dignity and our way in the world. And that we, as people with those rights, have a or should have a say in how we’re governed and by whom. That was the bet.

Did it work? Well, this is Thucydides. You all remember Thucydides and the Peloponnesian Wars. You remember these things, right? [LAUGHTER] This is a lesson in civics. You’ve all been there. So what he wrote here on the screen was why it didn’t work in Greece, in the Peloponnesian Wars. This is that famous classic history. And I’m not going to read this slide, it takes too much time, but the issue here is it falls apart.

John Adams, one of the founding fathers, as we call them, said that democracies die by committing suicide, seldom by outside intervention. They commit suicide. Read the daily papers. [LAUGHTER]

The next case I want to bring up here is this, the question here is: How did the democracy of the Weimer Republic after World War I descend in the world of Goethe and Schilling and great German philosophers. How did it become the world of Hitler and Himmler and Auschwitz? And so how did these people, the most educated people on Earth, how did they fall for Hitler? What was the origin of that? So how did this occur, and what are the lessons we could draw from that in our own life?

Now, second point: Is the US a democracy? How many of you think the US is a democracy? Let’s see your hands. Put them up really high. Shout. [LAUGHTER] Well, we established that point. I guess we move on. [LAUGHTER] How many of you are in favor of royalty? [LAUGHTER] The data is not encouraging.

This is from one of the great studies of American democracy by two of the best political scientists that observed this, and they say that your opinion and mine don’t really matter much. And so there effectively is—Think of this as the Grand Canyon, a chasm, and on this side there’s us and our public opinion, and on this side there are laws and regulations and so forth, and the bridge that ought to connect what we want as people and the policies and regulations and laws that we get over here is broken, or it’s been turned into a toll bridge.

So down this list of items here, we favor all of these things: healthcare, climate action, and so forth. You get down to here, what passes Congress? $1.4 trillion tax cut for people who really don’t need it. So we don’t get what we want, and democracy is broken.

Is democracy dying? The scholars, the people who study this for a living, believe it is, or at least it’s impaired. This is from the Economist magazine, and they have the United States as an impaired democracy and going south. The public opinion – this is from a poll the World Values survey – and what it shows is that virtually in every country, every democracy, support for democracy is declining. And if I broke this out into age groups and so forth, it’d say the same thing. The elderly, the middle class, young people, democracy is failing.

Now part of this goes back to the fact that—that pronoun issue – I, me, and mine. We’ve been focused on market solutions, and the climate change is going to respond to markets or technology, and those are important things, but not to political change, where we come together and we say, This is our country, it’s our democracy, it’s our policies, and they do matter.

I grew up near Youngstown, Ohio. Youngstown in 1941 was the wealthiest city per capita in the county. If you go there now, it looks like it was bombed down in World War II. This is very typical of the rust belt region. It’s not shiny like a lot of California is. It’s rusted out, burned down, disinvested. Cities like Detroit, and Cleveland, and Toledo, and Youngstown, Ohio, these are cities we now fly over. This is part of the flyover zone. So if you wonder why there was support for Donald Trump in the last election, a lot of it is found in the failures that we’ve pursued.

As Youngstown was declining, so too were the prospects of each generation. So this just shows the odds of people, young people, earning as much or more than their parents by 10-year periods. It’s going down. So if you’re a young person in Youngstown or in that rust belt, or in a lot of the areas in the United States we mark as a red zone, which will come up here in just a minute, you don’t see a future that your parents saw. That’s that map.

Now it isn’t quite that bad. A lot of those red zones are 47/53 in terms of support for and against, and so forth, but that’s the United States right now. And we here are in the blue zone, but we’ve got to find ways to reach into that red zone. We’ve got to reach out across these chasms.

This is from a report recently released – well last month – from the US Senate Committee, Joint Economic Committee. This is—What is circled here are deaths of despair – opioid addiction, drug addiction, suicide. It’s going straight up. This is my district, and this is called gerrymandering. You all know the term. This is how you have to gerrymander Ohio to keep the most far right wing Congressperson in office. And so that’s called gerrymandering and it happens. There are a lot of reasons. You—Most of you know all about that.

This is the transition of the United States. Now here in California, you have six cows and 40 million people. [LAUGHTER] Wyoming has 40 million cows and six people. But you both have two Senators. And so the way the Senate is going right now, very soon, 30% of the country will decide 70% of the Senate membership.

And then there’s this problem. We thought we had this solved at one time. When Barack Obama was elected president, I just assumed, boy, that’s great; it’s over; we’re going to win; we finally have crossed that threshold into acceptance and diversity. But we found it was a little premature. These are the hate groups across the United States that the Southern Poverty Law Center tracks. And there are probably more than this, and they’re well armed and they’re not quite with us yet. This is a problem of income. If you want to know why democracy collapses, go back into history. Plato and Aristotle said it collapses because of oligarchy. Democracy becomes an oligarch world. It’s ruled by the rich people and so forth. This is simply a diagram that shows the transference of roughly $20 trillion from the bottom to the top of the income spectrum – $20 trillion. That red bump down at the bottom, if you’re a working person, you’ve lost ground. If you’re one of those workers in Ohio or the rust belt states and you have to live by paycheck to paycheck, you’ve lost ground.

The question is: So what? Why don’t we just become an epistocracy and rule by expertise? Why don’t we do what China is doing? Surveillance, democracy, and imprison dissenters. Democracy really doesn’t work, and again, it does seem to commit suicide fairly often. Thucydides’ comments are still relevant to our world today.

Let me give three reasons why we have to defend democracy, and this is where we’ve got to come together as citizens to understand how we conduct the public business in ways that’s fair and decent and sustainable. So this is Jim Hansen, the best climate scientist – certainly the most famous climate scientist – in the world. That’s right, you can applaud. [APPLAUSE] He is a genuine hero. [APPLAUSE]

Jim Hansen, the quote here says that you can’t fix climate until you fix democracy. And that’s really inconvenient because we don’t have much time to fix climate. The IPCC about a year and a half ago said we had about 12 and a half years to fix it, but we’re down to say 11, or whatever the number of months it might be, but that doesn’t give you much time, not on this planet with this much infrastructure, and that long way to go. But 11 to 12 years to deflect carbon emissions downward.

So why do we have to fix democracy? And you begin to think about the reasons here. This is going to be an all-hands-on-deck time for us. We’ve got to all of us get engaged. So all of you who are organic farmers and permaculturists, and all of you who are business people, and all of you who are educators, we’ve got to come together, and we can only do that if our votes matter, if our policies are supported, if we can bridge that gap from this side to that side.

And then there’s this point. Wait, I want to skip over that slide. There’s this point, and this gets into some kind of difficult things. Can you imagine a solar powered, sustainable, resilient, hyper-efficient, fascist society? [LAUGHTER] Now think about that, because the bottom of this explains what fascism is: ruled by oligarchy, misogyny, racism, and so forth. That’s the daily headlines. Do you see any difference between the bottom of this slide and the top, the prospect? Not much. And that’s where we’re headed.

And then there’s this: Shoshana Zuboff is one of the great lights at Harvard Business school. In that quote at the top, describes the inherent dignity of people. Democracy may be, as Winston Churchill once said it was, the worst form of government, except for all the others that have ever been tried. [LAUGHTER] But even in its imperfections, and it is imperfect, but it’s the only system of government that says you and I matter, at its best, not always, not everywhere, not any one place all the time. But at its best, democracy does matter.

And then the bottom quote is from C.S. Lewis who concluded—the theologian—that he wasn’t fit to rule even over a henhouse, as he put it. So the question is: Who among us could be the ruler, the king, the emperor? Who has that level of wisdom? It would have to be somebody with a really, really big mind and great foresight and so forth, and the hutzpah to tell you what a great mind he has. [LAUGHTER] Nobody. Nobody, Lewis’s point has that claim.

So what do we do? [LAUGHTER] I want to issue a caution here. I don’t think we ought to be directed solely at Donald Trump, No. 45, because what he did – and we ought to also give him a round of applause, because what he did was to highlight everything that was wrong and had to be fixed. He took a highlighter [APPLAUSE]… essentially to everything that we need to undo and redo and rethink.

So the end of the stalk is going to be we don’t need to repair democracy so much as we need to invent the first ever democracy, true democracy. [APPLAUSE] So this gets personal. We started after the election. I, after the election of 2016, I went into a deep depression, and I was ready to retire and go off and do what old white guys do and play golf, and bowl, and things like that. [LAUGHTER] Neither of which I do well. But the—Or with any particular joy. [LAUGHTER] So what we did was to organize a conference. And what we were looking at here was like looking through the rearview mirror. How did we get to the election of 2016?

So this, by the way, is a new hotel we built entirely solar powered, platinum building. That’s where we had all these gatherings. Tim Egan from The New York Times and a whole series of wonderful, far-out speakers, the one on your left there, I’ve forgotten his name, but you see him in movies. We brought people together. This, by the way, is [Peter Wehner] on the right, on your righthand side, and Bill, former governor of Colorado – I’m blanking on his last name. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] Bill Ritter. That’s right. And you know what happened here? This was interesting, because we put them on the stage together and we asked each to explain how you would repair liberalism or conservatism. And you know what? The conversation was civil, funny, productive, creative. Imagine that in American politics. It can happen.

Reverend William Barber was like an exclamation mark at the end of the event. [APPLAUSE] And so when you come to think of what ails us, it may be economics, may be technology, climate change certainly has both of those elements to it, but it’s moral. And William Barber pointed out that this is a moral failure before it’s anything else, before it’s even a political failure.

So this is the next part of this. We’ve pulled together 34 authors – Bill McKibben, who’s here, and a lot of very, very bright people, K. Sabeel Rahmann, and Ganesh Sitaraman, and so forth, Jessica Tuchman Matthews. And we assembled a book: Democracy Unchained. We took Nancy MacLean’s book, Democracy in Chains, and inverted the title. She’s on our advisory board, by the way. And the book comes out in mid-February of 2020. Make your order. So if you have a smart phone, order it on Amazon. [LAUGHTER] You can pre-order.

And then we’re following that with events that are on the right side of the screen. The opening event with authors and others will be at the National Cathedral March 25th of 2020. And then we do events in Boston, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Denver, Los Angeles, San Francisco. What we want to do is start a conversation, a conversation about how we rebuild first American democracy. As you’re bringing this democracy into an emergency room, you’d stop the bleeding and stabilize the vital signs first, then you get to lifestyle changes. But the long-term conversation we have to have is how do we build a democracy in which all of us in fact do matter.

So that’s part of this. And then government, trying to restructure government, starting with the words that we use. Let’s reclaim our public language. How did the word conservative become what it has become? Or how did the word liberal become so disparaged? Those are flip sides of the same coin. Everybody in this room, on one issue or another, you’re conservative or liberal, but you’re both. It’s called a thinking person, not a ditto-head. [LAUGHTER] [APPLAUSE]

And then why governments matter. I don’t have time to read this, but begin to think about what we do in the public arena. We need government. Not a government that’s been defunded and defrauded and depersonalized and all those things that we’ve done in the past 40 years to disparage government and to disparage the idea of public service. We need government, but we need government of the people, and by the people, and for the people, that’s transparent and effective, and all of those things.

And so what’s to be done? Well, here’s where we at Bioneers need to think through how hard this is going to be, and think of the heroes and heroines in this room, people who have sacrificed and who have risked a great deal. That’s all of you. We’re going to all have to risk, we’re all going to have to sacrifice something to make this dream come true.

Frederick Douglass said power doesn’t give up, never easily. And so it hasn’t. So what’s this change look like? Well, this is part of it. It’s the power that we have to be citizens, the power that we have to be foresightful, the power that we have to engage power and tell the truth. And so… [APPLAUSE]

We’ll just call her what’s-her-name. She’s up there. Imagine 13 years old. Now she’s 16 or so. Imagine the courage she demonstrated. Like lightning on a dark night, she illuminated the terrain.

So imagine democracy unchained, from what? All those isms, all those human failures and frailties and sins. Imagine a real democracy – us, we, ours – where all votes are counted. The right to vote in fair electoral districts is guaranteed. Our representatives both in state legislatures and county legislatures and federal government and so forth look like us, they’re diverse and are not old like me, all of them. A few of them could be old. [LAUGHTER] Imagine publicly funded elections. Get money out of politics once and for all. [APPLAUSE] Imagine that you have the same healthcare benefits guaranteed to Mitch McConnell. [APPLAUSE] Imagine a democracy in which corporations are not persons. [APPLAUSE] Imagine a democracy in which ecocide is a crime against humanity and punishable as such. [APPLAUSE] Imagine a democracy where lying and systematic deception is wrong and is a crime, and that includes Facebook, that includes television, that includes all the media. Imagine a democracy that would protect our lands and waters, as my friend and that eloquent writer, Terry Tempest Williams, who will be out here in just a moment when I get off the stage has said for so long, imagine our public domain protected by a democracy that is competent and ecologically alert. [APPLAUSE] Imagine a democracy that would protect the global commons. Imagine a democracy calibrated to the way the world works as a physical system, that Bioneers and all you Bioneers for years have showed. Imagine a democracy in which justice flows down like a mighty river. [APPLAUSE] Nirvana. No, this is planet Earth, not nirvana.

But only a government of, by, and for the people in which we have no malice toward anyone, but charity for all. Thank you very much. [APPLAUSE]