Staci K. Haines, the founder of “Generative Somatics,” has integrated her extensive experience in both transforming individual and social trauma and in grassroots movements into uniquely powerful work that has proven to be incredibly helpful to a wide range of social justice activists, many of whom have been deeply hurt by oppression or violence. In this panel, leaders from a range of cutting-edge groups, including Prentis Hemphill of Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity (BOLD), and Raquel Lavina from the National Domestic Workers Alliance, share how they have been able to successfully integrate embodied transformation into their social change work. Transcript below edited for easier reading.

STACI: Hi All. I’m Staci Haines with Generative Somatics. We’re really happy to be here. So I’m going to hand it to Raquel first. Can you kick us off?

RAQUEL: Hi All. I’m Raquel Lavina. I’m with the National Domestic Workers Alliance, and we are nannies, housecleaners, home-care workers, part of the biggest growing industry in the whole country, right, because of so many people aging, people with disabilities, and young people, and homes that need to be cleaned. Yet we’re some of the most exploited workforce in the country. So we’re a national alliance, and we have a goal of building a membership association of 250,000. We’re halfway there.

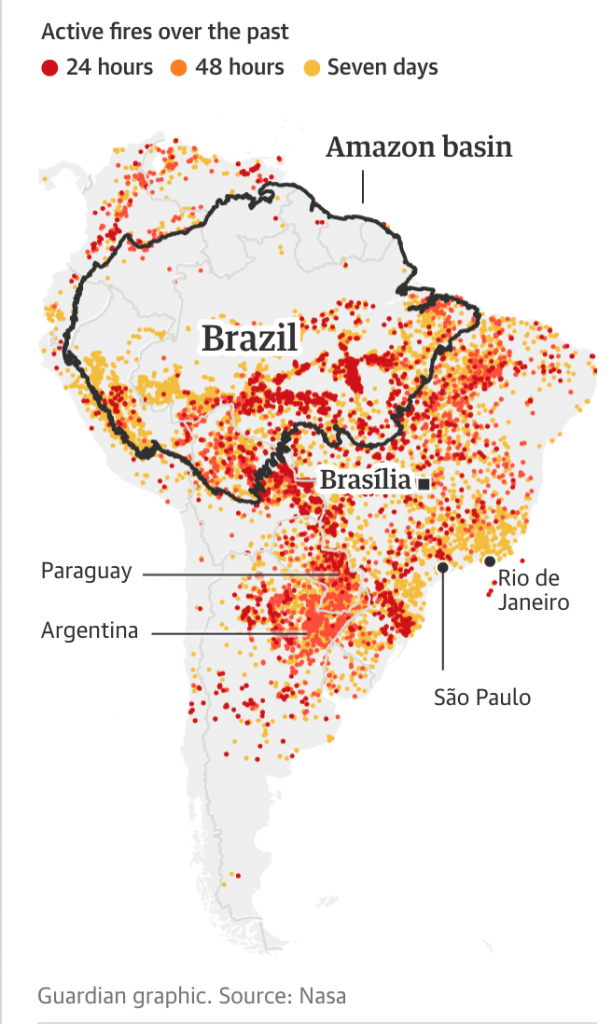

And we also help lead, in terms of building a broader progressive movement, because it doesn’t matter if we have better conditions if the rest of the world’s on fire. So we both do organizing with domestic workers and in the progressive movement.

STACI: Raquel, will you also tell us a little bit about you?

RAQUEL: So I come to this work as someone who’s done organizing, who helped build a lot of youth organizing a long time ago in the Bay Area, and to me, bringing people together to build power was really important and powerful, and the ways in which we were organizing was not generative, it didn’t nourish us. So I have both a background in organizing, in domestic violence, in healing, and I think there’s probably some way to bring this all together.

I came to Generative Somatics with an idea of using the system of organizing in a way that helped us model what we want to build in the future and heal along the way, and that way our visions could be bigger and longer term, and our present could be a lot more healthy and powerful.

PRENTIS: Hey Y’all. I’m Prentis Hemphill. I use pronouns they, them, theirs, and I’m here today representing Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity or BOLD, as you will hear me call it as we talk.

BOLD is a training program for black organizers, movement leaders, that is really focused on rebuilding infrastructure of black movement. And in that project we deeply integrate somatics, deeply integrate embodied leadership, as well as political education and transformative organizing.

I’ve been organizing for a while now, longer than my face reveals. And I mostly started working around prison abolition, and just understanding the impacts prisons had on my community, on black communities, on my family all my life, and really, as I got deeper into that work, so much of the pain and trauma that we’ve experienced for so many generations was really revealed to me, and I stopped that work for a while and became a therapist. And I was working—I didn’t really stop that work; that’s not true. But it kind of shifted how I did that work. And I focused on building my skills to support healing for my folks, for my communities. And I did that for a long time, and then felt really kind of stuck and siloed, and that too I was like, Oh, we’re not able to talk about how oppression is traumatizing in this context? We’re not able to really talk about how people can organize or act back or shift conditions, or how everything needs to be restructured actually to prevent the kind of trauma that we’re experiencing. My work has been about merging those back, and I’ve been doing that with these folks at Generative Somatics for many years too.

But really, how do we heal on a level that we need to heal? How do we shift structures? How do we build power on a level that we need to to actually feel freedom in our bodies and in our lives? So that’s what I do. [APPLAUSE]

STACI: So I’m Staci Haines, just to do a little bit more of an introduction on myself. I have been co-building Generative Somatics for the last…coming on a decade, with many folks, including Raquel and Prentis. I too, like them, have had a very deep passion around how do people transform, how do people change, and then how do social systems change. As many of you are probably familiar with, those end up being super different schools of thoughts and different schools of action, and that did not make any sense to me at all.

So I’ll say a little bit more when we are speaking, but I really followed both of those paths: What are the ways I can find to help people, including helping me, around healing trauma, and also just building more empowerment and skill and choice? And somatics really became the method that I was like, Wow, this is working really well with a lot of different people.

I also have been active for a long time. I started in campus activism, and then really focused on work around sexual violence, and then particularly around child sexual abuse. How do we end the sexual abuse of children? What would we need to change to do that? All of that integrates into more of stories we’ll tell.

I’d like to also share that I’m a new grandma! And that’s a trip. I’m like, When did that happen? I don’t look like my grandma did. All these next generations, that’s who we’re working for, fundamentally.

Because it’s somatics, we’re going to start with practice, play? Basically somatics is a methodology for transformation that leads to embodied transformation. And what we mean by that is that we’ve transformed when we can take new actions aligned with our vision and our values under the same old pressures. Right? So we do not hold new insights as transformation, we just hold new insights as new insights. That’s awesome, but most of the time we can’t take new actions consistently off of new insights, so “embodied transformation” means that we have put a new schema into our psychobiologies. We’ve actually put new memory into our musculature. We have let go of deep patterning and often wounding or patterning of privilege that has shaped us up to this point. So our vision, our values, our actions, how we build relationship can be aligned, even under the same pressures. even under the social systems that we live in. So that’s really what somatics serves.

We define transformation as when our actions align with our vision and our values, even under the same old pressures. We can be and act and build relationship differently. We can organize differently. We can build movement differently, even under the same old pressures. So that’s what we’re looking at inside of somatic transformation or embodied transformation.

Soma just means the living organism in its wholeness. Basically there’s no good English word, so we’re stuck with soma. Okay? But it means all of us – mind, body, spirit, relationship, action.

PRENTIS: Alright, y’all. So we are going to practice. And one of the foundational practices inside of somatics is this practice that we call centering, which is really about how do I get present with what is; how do I feel myself and notice what’s there; and then how do I intentionally shape myself or feel my shape so that I can take the action I want to in the world. So we’re going to do that practice together, and it can be done either seated or standing. You can choose. I’m going to be standing. I just want you to get into a position that allows your body to be both relaxed and alert.

And before we center, we just want to take a minute here to just drop in and notice who you are, how you are right now. So with breath, we can notice: What kind of thoughts do I have right now? We can notice also: What kind of mood am I in? And none of this we need to change, we just want to be able to be that presence that notices.

And then we want to really feel and notice on the level of sensation. So what’s actually happening in this body, in this organism? And you can here look for temperature: heat, coolness. You might notice different regions have different temperatures. Just notice that… You might also notice tightness… You might notice pain… You may notice movement… Or you may even find places where there’s numbness, where you don’t feel anything at all… And with all of this, we want to increase our curiosity. Just what is? What is? Not trying to shift, not trying to tell a story about it…

And then from here we want to center intentionally. So I’m going to ask you to bring your feet about hip width apart, just make sure you’re there. And if you can even try to find it without looking, if you can just feel it. Bring your eyes open if you can, and in the room, because here we want to center, and also be a part of. We get really good at centering and being alone. We want to center and be with. So here, dropping in this place we call center, we locate it about one or two inches below your belly button, so you can put your hand there.

I really want to ask you to bring your breath, your attention, your presence to this place… letting yourself drop in. And so really imagining this place, it’s a 360 bowl. So if you want so you can feel it from the inside out, inside to your hand… So much energy that emanates from this place. And from here we want to intentionally use the energy here to center on purpose, so allowing ourselves to center first in the dimension that we call length. You might feel yourself kind of—let gravity have you. Like if there are muscles holding, let them surrender a bit more to gravity. Feel your connection to the floor, to the earth underneath you… And then simultaneously let yourself kind of naturally, easefully extend upwards. You can imagine there’s a string at the back top of your head that gets to extend upwards towards the sky, but here letting space be between your vertebrae, letting your chin come level… and letting breath be here the whole time as you feel this length. And this is where we say, in the somatics lineage, is where we express our dignity. This is the dimension through which it gets expressed. And it’s also the place that we can witness dignity in each other.

So I want you to just take a moment, bringing our eyes, making sure our eyes are here in the room, but take a minute and check out the dignity in this room. There’s inherent dignity in each person inside of this room that cannot be negotiated, taken away. It’s inherent.

And we also get to be an invitation to dignity. You can think of it as a competitive sport sometimes. I get to have my dignity, therefore, no one else can feel it in the room. We get to practice here: How can I be in my dignity and also be an invitation? I want you to have your dignity. How does that feel? It’s looking good on y’all. [LAUGHTER]

And then we get to center in our next dimension while holding onto this length. Right? We don’t need to lose this, we can kind of feel it out. We also want to center in the dimension that we call our width. So really just let yourself feel yourself side to side. So you might feel ear to ear, shoulder to shoulder, feel the width from the side of your hips, knee to knee, feet to feet, really let yourself feel: What’s my natural width? Can I relax into that width that allows me to just be open? See if I can breathe into, feel that width, and then also feel for the people around you. Just feel for them. Perceive them without looking, just feeling. And seeing if you can find that place where you can let yourself out, but you can also listen, connect.

And this is a dimension where a lot of us can express our boundaries. Right? We can shrink away, we can bring it in. We can also connect here. We can be vulnerable here.

And let’s center here into the dimension of depth, and again, we get to hold onto our length, our width, and then also feeling into our depth, feeling for your back body. Western culture can be so front-body oriented – What are we doing? What comes next? What comes next? We get to feel some of that back body. Feel the back of your head, your neck, the clothes on your body. Feel your butt, the clothes on the back of your legs. Feel your heels. You might notice that your weight wasn’t on them. Can you bring some more weight to your heels?

And here with your breath, let your kind of back body open up, relax. And here we might bring in our lineages, our ancestors. Who has our back? And let that be some of the support that we get to rest into. You come from somewhere. Like it’s to be behind you, you get to resource what you need from there.

And then moving in and through our bodies, letting ourselves feel in and also soften along our front, so feeling forth. If you have glasses on your face, feel those for the tip of your nose. Feel the clothes on your chest and your torso, down your legs. And then kind of facing into now. Here you are, bringing yourself present.

And then the last dimension we want to center around is what we care about. So if can just, from your center, kind of listen into: What is it that I care about? What is it that I’m here to do? What am I up to? What am I really committed to? And let whatever that is organize you a bit more. So if that’s true, what about your length, your dignity? If that’s true, what about your width, your connection? If that’s true, how do you relate to your lineage or history? Let it shift something in you. Let it show up on you.

Take a moment to note to yourself: What’s my mood after that? What’s there? What’s showing up? And just let it be with you. Thank you.

Prentis Hemphill and Staci Haines

STACI: Inside of all the practices that we do there’s a principle. So we’re practicing embodying something, and with centering, like Prentis just shared, we’re practicing getting present, open, and connected, and on purpose. Right? And then somatics is very pragmatic. There’s like a how-to – How do we do that?

So we’re going to do one more practice before we kind of dive into chatting more, and this is a practice we call hand on heart or hand on chest. And this is about how do we center and invite—bring our center to someone else at the same time. Like how do we build connection and relationship from purpose, and from being present and connected.

Turn to someone near you, take a moment and introduce yourself, because this is—You’re going to need a partner for this practice.

[AUDIENCE PARTICIPATING]

STACI: So Prentis and I are going to model this. A lot of our practices are based on standing, to give people more access to feeling our lower bodies. A lot of time we’re a little numb from the chest down or the eyebrows down, just depending. [LAUGHTER]

Okay, so what we’re doing inside of hand on heart or hand on chest is if you’re standing you just go same foot forward, and then we ask permission: Is chest okay, or shoulder? And same hand and same foot. I’m going to just place my hand on Prentis’ chest. So you want to move at all?… Awesome. Okay. But what we’re basically doing is we’re connecting center to center. So I’m really bringing my center to this connection, and then inviting Prentis to do the same thing. And then we’re going to ask a question with each hand, and just let your body answer the question. Like you don’t have to figure it out, you don’t have to think about it, just let your body answer the question: How does oppression cause trauma?

So that’ll be the first question. Then we’ll change hands, change feet. Center to center here. And then the second question is going to be: What does healing have to do with social change? Okay? You’re going to go both questions in one direction, then you’re going to switch roles, ask the same questions to your partner. Yes, question…[AUDIENCE ASKING Q] Oh, your mouth actually answers. [LAUGHTER] Your mouth is your body too, but good question. You will verbally answer the question, just don’t think about it. Like don’t figure out the answer, just let yourself answer. Right? So you might learn something in your answer too.

RAQUEL: Thank you all for jumping in. That was really beautiful, actually. So some of you knew each other and some of you didn’t, and that’s a practice in how am I really in myself, and how am I really connected to somebody else in themselves, and asking a genuine question, and hearing a genuine answer instead of the like, How are you, I’m fine, Bye, that we normally do. And we want to take time to do that.

So we actually just want to ask two people, tops, there’s a mic right here, and I just want to ask you how that was for you, and if you learned anything from connecting with somebody in this way.

AUDIENCE MEMBER – Great to drop in and see if any trauma has affected me, or oppression has affected me. Needed a definition of oppression, and missed it. And was needing a definition of social change. If you could frame that.

AUDIENCE MEMBER – Found it incredible. The power of the touch is incredible. Was moment where they went so fast through it, couldn’t even remember what was said. Wanted to capture it for the more cognitive part of self. Answer was immediate.

RAQUEL: Awesome. Thank you. So we’re going to our next part of practice, which is us doing a bit of talk about how we incorporate this into our work. Definitions of oppression and social change will come up through that.

So how I want to do this is like actually the three of us know each other for a while, and so we could just sit here and talk for 45 minutes with each other. We’re not going to. [LAUGHS] So we’ll each say a little bit about how we do both social change and somatics and healing together in our different areas. Staci will start it off, she’ll talk a little bit, and then we’ll actually ask if you all have any questions or comments about what she has. We’ll move to me, and then to Prentis, just so we have a chance to dig a little deeper, because we’ll talk about fairly different things.

And then we’ll try to save some time at the end. So I just wanted to give you a little structure of how it will be. And then we’ll just figure this out. We already like figured out how to center in hand on heart in this big room, so I trust all of us.

All of us come from organizing or being in groups of people, collectives of people on this panel. I’m sure a lot of you do as well. And whether or not you talk about trauma, it’s there. Right? It’s in the room. It informs how people behave with each other. I always experienced it as like—I just felt like somebody just vomited on the room. Right? Because it’s just there.

And a lot of times, in organizing, we can say, Let’s ignore it; let’s just try to ignore it because we still have to take action. Or in healing, we can say, Let’s help this individual go deep into their trauma and try to heal from it. So what we’re trying to keep teasing out with each other is: How do you do healing in collectives? How do you deal with trauma so it becomes part of what is in the room, but it doesn’t define the room? And we can take action together.

How we define the somatics is you have a brain in your brain. Right? You have a brain in your head. You have a brain in your heart, and you have a brain in your body, or in your gut. And if you just use one of them, you’re not using the full amount of information or your full self. So the point of our somatics when we’re working with domestic workers is: How are we at all times using the intelligence we have here, the intelligence we have in our heart, and the intelligence we have in our body.

STACI: So I walked into my first psych[?] somatic transformation/healing space in 1995. What was amazing, and I found this in a lot of spaces, as I was seeking my own healing – I was also healing from my experiences of trauma – as I was seeking my own healing, what I found was most of the healing spaces were primarily white, they were primarily upper middle class and owning class white folks, and I was always the one on scholarship. I’ll tell you I’ve cleaned a lot of people’s dishes to get my healing. Right? So I’d apply for scholarship and then I’d do a bunch of work before and after the day started.

Now what I also found in somatics is I was like: This is so powerful, like I transformed and I saw people transform in ways that I had never seen before. Again, very holistic, a deepening of their emotional confidence, a letting go of certain impacts of trauma that I didn’t even know were possible to let go of. So I knew something very powerful was happening in these rooms, but in the other time in my life, I was out doing activism. Right? So I was doing activism, I was working around sexual violence prevention, white anti-racist work, and it was like I—the bridge between the two seemed so far apart. Yeah?

But one of the things that I see in transformation work that does not have a social analysis is that we can do transformation that leads to the same social systems of oppression.

Here’s what we mean by oppression, and I really appreciate people saying, like what are these words and what do you mean, because I’m sure we have a wide array of us in the room. Some folks that makes sense to them and some folks not. But oppression are systems, structures – right? – like economy, government, media, education – right – these big structures that have these big, long histories that basically say certain peoples, certain groups deserve safety, belonging, dignity, and resources more than other groups. And so the ones who deserve tend to think, Oh, I just earned that myself. Right? That’s part of how privilege works. It’s like, Oh, I earned that; that’s just mine. Instead of seeing that there’s systems that keep handing safety, belonging, dignity, and resources to certain groups, taking it away from other groups to do that.

Oppression is all the people it gets taken away from and the land. Like no one is out there asking the land if we can exploit it. Right? Or fixing it once we do. Oppression are these systems that take away from certain peoples in a structured way, a predictable, ongoing way. Power gets concentrated. Power, resources, safety, belonging, dignity gets concentrated with certain peoples and taken from others on the land. Exactly. Yeah.

So white supremacy. We’ve all heard about white supremacy. Right? So that’s one way. It gets concentrated, especially in the US, with white folks, wealthy white folks, and taken away from and hurting communities of color.

Male supremacy, sexism. Right? That’s another way it’s structured. Right? Did anyone get to watch the Kavanaugh hearings? I’m like, How is it 2018…Wow, here we are again. Still…exactly. Here we are still. Okay.

So, but here’s the thing. Y’all, some of you, might have been in those transformational rooms where what folks are transforming for is to get better at privilege and capitalism. Whoops! [AUDIENCE RESPONDS] Right? That is not what we want. But because oppression and privilege become unconsciously embodied – right? – here’s the link we’re looking for. Like I cannot agree with the social systems that I live inside of, but I still embodied white supremacy. How could I not? It’s been what I’m soaking in. I have to proactively do something about it to line myself up and line my embodiment up with my values.

I can’t tell you how many totally awesome male activist folks where I’m just like, Can you please do a little bit deeper dive on your sexism? [LAUGHTER] Right? And I trust them and know their values, but if you don’t do the internal work . . .

Well, the same thing happens. Like I was in that somatic room, and these are—I mean, I have stuck with this lineage and this approach for 23 years because it works. But when I was there, there was no social analysis going on, and so many of those people were going, Great, I’m going to use my transformation to get richer; I’m going to use my transformation to be a better leader, but I’m going to be a better leader inside of Exxon. So this is what happens.

And, again, all love to all of the transformation that’s happening in the Bay Area. I live here too. And the transformation that has really grown much more in the last 25 years in this country. But it is a rare meditation teacher that says, Meditate, and then go get socially active; meditate and wake up about how you’ve been shaped by our social systems that’s not life-affirming. It’s the rare somatic teacher who does that. It’s the rare therapist who does it. It’s the rare transformational workshop leader that does it. Right? So really what we all are committed to and about is these cannot be separate. Our personal transformation has to be—have a social analysis and understand the social structures we live inside of, and serve to transform them toward equity and life. Yeah? [APPLAUSE]

Staci Haines

Personal transformation, social transformation, same thing. Let’s just have a super strong bridge between those two. One, we’ll get way better at being social change leaders when we’re more healed. Right? I’ll be more awake. I’ll be a more awake human being the more I heal and transform my own trauma and my own privilege. Right? I’m a better leader; I’m a more trustworthy leader that way. And because oppression causes so much trauma. Right?

I am working on a book that will hopefully be next fall if I get it done by my deadline. But I have two minutes…

Okay, I’ll just tell this story because here’s what’s coming. I don’t have a title yet, sorry, but it’s about this theme. It’s about the bridge. Maybe The Bridge will be the title. But I remember sitting in my younger activist days, and sadly this happened two months ago too, in rooms of people who deeply cared about social change, and the amount of trauma and the amount of acting out on each other that was happening broke my heart, about the world that I really long for for all of us. And I so appreciate—To me, social activists have chosen the hardest job in the world. The hardest thing to do is to change broad social structures toward equity and life. It’s a really big job. Right? Millions of us need to do it. But sitting in those rooms and seeing the impact of trauma and oppression without access to healing? It’s not actually creating the biggest visions and strategies that we want and need. Right? And sitting in rooms that have had a lot of access to healing, to healing trauma, to meditation, to transformative work.

What’s so hard is you bring up racism in that room and people flip out. [LAUGHTER] Or you say, Can we talk about actually the negative impacts of capitalism? And people get pissed. [LAUGHTER] Right? So it is, it is really that bridge of like can we wake up inside, and can we wake up outside, and then do something about it together. Yeah? [APPLAUSE]

RAQUEL: So we can take three people coming up, either a question or a comment, and just come to the mic because they are recording this session.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: They get pissed because they’ve already dealt with it?

STACI: Sorry. That was kind of a shorthand…No, what I’ve noticed—We just led a four-day training of a – I’ll just call it a very large funding community. [LAUGHTER] No, it’s all good. It’s like people with their hearts in the right places, and when we really said our economic system is exploiting a lot of people and the planet, there was a lot of discord and dissonance and upset in the room to question global capitalism. Yeah, and these are also people who have done a lot of transformation work. So that’s what I meant inside of that. Obviously you weren’t there. [LAUGHTER]

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What did you then do when they all got pissed off?

STACI: No, it was good. So this is also what’s so important, is by developing and growing ourselves – right – and, again, we do it through somatics – is our capacity to hold complexity increases. Our capacity to hold contradiction increases. Right? And we need that to get through what we have in front of us. Right? I needed that to love some of the people that I spend those four days with. Right? I really had to go, What is my purpose? What do I care about? And I can hold this complexity and we can keep engaging. But that all really came through practice. And also we invited them into practice. So we did four days of somatics with these 90 folks. And we had a lot more room. We needed a lot more room than we have in here. But really asking deep question about their purpose, about the purpose of the organization, about the world they wanted to leave behind, and what they actually wanted to invest in. And it was very important that that was answered from a place that allowed for their own complexity, that was felt instead of just thought.

It’s a lot easier to learn. This might sound weird, but it’s a lot easier to learn and to open to new things when we can tolerate feeling our own sensations. Like usually if we can’t stand what we feel, that’s when we shut ourselves down or shut someone else down. Does that make sense? Right. So somatics helps us open more and more capacity, and then it’s almost—like gives us more space to learn, change, grow. Thank you. Thanks for the question.

RAQUEL: Yeah, we can take these two, and then we’ll move to Prentis and myself.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: It seems like the model for helping people with individual trauma is to help them feel more comfortable, and that social change is about creating lack of comfort, to look at things that are distressing. How do you work with that window of tolerance of discomfort?

STACI: Great question. Great. I would not say healing is comfortable. I think healing is one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. Like for reals. [LAUGHTER] I feel more comfortable now, but that was hard. [LAUGHTER] But what I appreciate about what you’re saying is to me both healing and social change work ask us to develop a competence, an ability to be with the unknown, and the unknown is uncomfortable. So healing you’re like, Ugh, facing the pain, letting that process move through, expanding. Right? Getting more connected and being like, Oh, this is what love is? Right? Like all that. And then social change, it’s like, Oh wow, this is what’s known, and we also have to go into a space of unknown, toward the possibilities we’re creating. So I think in some ways they require similar capacities, just one more internal and one more external. Yeah? I like your question, though, thank you.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Why is it uncomfortable for white people to talk about racism?

STACI: Because we feel deeply ashamed. [AUDIENCE RESPONDS]

AUDIENCE MEMBER: You’re ashamed because the history of slavery and ancestors?

STACI: I love this conversation! [LAUGHTER] Yes, I think not only the history, like I think current time, current time racism, the history of slavery, the history of colonization of this country. When you start waking up as a white person, there’s a lot of shit to face. Right? But I think it’s also because we pretend we’re a post-racist society, and I think white people have very little tolerance – like this is a place we need to build somatic tolerance, as white folks, to be like, Okay, racism… Do you know what I mean? Like we have to build a tolerance to feel it, to talk about it, to face it, to feel horrible about it.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: But don’t you feel horrible about being privilege too sometimes?

STACI: For sure. I think that’s exactly right. Any place we have privilege, I think we have to open up our capacity for empathy and for accountability.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Okay.

STACI: And I think both of those ask us to like really have to widen out and be able to feel more, more discomfort. Right? More discomfort, more like finding the path through to basically—

RAQUEL: Take different actions.

STACI: To take different actions and to be actually in solidarity with multiple other groupings of people to create change together.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Privilege can be opportunity to do something about those who are oppressed.

STACI: I’m right there. [APPLAUSE] I am right with you. That’s what we’re doing here. [LAUGHTER]

RAQUEL: Good thing that was a segue into what’s coming next. [LAUGHTER]

So I’m going to talk a little bit about how to take – right – this methodology, this commitment that Staci saw. Right? How do we take this from individuals and apply it so that we can change both ourselves and the systems that govern our entire lives.

And so Prentis and I have both been in a practice of bringing somatics into different communities. So I work with low-wage workers. Right? So how does integrating an analysis of what’s happening, organizing as a main strategy to build power, and somatics as a healing methodology for individuals and collectives, how does integrating all of those bring us from being low-wage workers to people who can build a new kind of power in this society. Yeah? So that’s what we’re—I’ll talk about domestic workers, and then Prentis is going to be talking about building black organizers, leadership, infrastructure, movement, and liberation. So hopefully this helps answer this segue you set up for us.

What I do want to start to say is the reason why we felt like it was so powerful to bring, to integrate analysis, organizing as a main strategy, and transformation, somatic transformation into a domestic worker movement is because as domestic workers, people are in one household. Right? So it’s not like a factory floor. Right? You’re not all working in the same place. So it’s a really isolating industry. It’s also an industry that was created by slavery, by patriarchy, by white supremacy. Right? The fact that it’s like women’s work, domestic work is undervalued – we’re paid the least of almost any worker – is because it’s work in the home. And some of the legacy of slavery is that both domestic workers and agriculture workers were the two industries that are legally not able to collectively bargain on their behalf. So we can’t set up a union legally. Right? And those were the two industries that most people who were coming out of slavery ended up in. Right? So instead of having black people in this country be able to set their own wages, get their own benefits, have some hours – like an eight-hour day – we are not allowed to collectively bargain.

So our whole thing is: How do you bring people from individual households together into alliance so that we can make sure that all workers – right? – have fair standards, have fair wages, have benefits, have some structure to their life, and are treated with dignity? And if you do that with the lowest-wage workers, that means you’re doing that for everybody. Right?

So that’s where we came from. And everyone’s like, Domestic workers can’t be organized, how are you going to find them? Well, we found them in the parks, on the buses. You see somebody with a broom, you’re like, Hey! Right? So we grew from like maybe a few hundred to now we’re at 120,000. [APPLAUSE]

And so our whole thing, as a movement, we’ve actually had to be super experimental, really creative. Right? And that goes against the idea of a domestic worker as somebody who is not their full self, who is super exploited, who is super isolated. We actually had to encourage connection, creativity, resourcefulness, experimentation. So bringing this methodology into the domestic worker movement was actually really powerful because we were already set up to say, You know, we are not defined by the job we do in somebody’s house and the job we do in somebody’s house is valuable. Right? All work is valuable.

So what I’ll say—I want to share a little bit about how that went the first few years. And Staci and I worked on a program together with a bunch of the other leadership, and I think we’ve done three cycles and have trained about 300 leaders in the alliance. And our—We had multiple retreats throughout the year, where we focused on analysis, we focused on organizing, we focused on healing. And I’ll say some of the most powerful moments were our trauma weekend. [LAUGHS] The healing in trauma weekend where we had a room of 100 domestic workers learning how to do body work with each other. Right? Something that you have to pay $150 for an hour to a body work therapist. Actually we were trying to do this with each other in a way that was building connection and intimacy, and also creating the situation where people were experiencing trauma and either acting out with it or trying to stuff it down, but through healing each other, that experience of trauma was something that was able to come up, work through them, come out, and just become part of their lives, not the thing that defined their lives, not the thing that defined their value, not the thing that defined their dignity. And that created so much more openness and confidence. You could see from the beginning of the year, somebody came in and was like—Came in with the attitude that you might expect a domestic worker to have, like subservient, I’m here, just please, thank you for teaching me something, to the end where they were like, This is mine; I helped create it. This is what we want to build. These are the things that we want to have in the world. And there was so much confidence and openness, and you could see that happening over the course of the year.

And that wasn’t enough. Right? Healing is not enough. Then we have to move to taking action. So the last thing I’m going to share…

So everyone remembers when MeToo burst on the scene? Yeah, last year. So Alianza de Campesinas the farm worker women, sent this incredible letter to Time’s Up, the Hollywood actresses, that wasn’t like, What about us? You’re not looking at us? You have all this privilege. But was, We’ve experienced sexual assault in the field. No one ever sees it, and we’re so glad you’ve shown a light onto this, and let’s work together. Let’s both be full human beings going for our dignity, and try to change the whole thing. [APPLAUSE]

So what we learned, because domestic workers and farm workers, we have a natural alliance, right, since we’re both not allowed to bargain on our own behalf, we got together and we realized that actually the laws of the country – right, so sexual harassment laws that govern workplaces – only apply to workplaces that have 15 or more people, and they don’t apply to independent contractors. So almost no domestic worker is covered by federal law, and almost no farm worker is covered by federal law. Not to mention like once you actually do file a report, whether or not it gets investigated, whether or not any reparations happen is a whole other thing. But from the beginning, domestic workers and farm workers were not covered by federal law.

So we said, Okay, let’s do something about this. Again, if you help all workplaces or the people who are most exploited, then all workplaces change. So it’s not a competition with Hollywood actresses, it’s a let’s-actually-take-care-of-the-whole.

So a lot of domestic workers started to come out and talk about their stories of sexual harassment on the job that happened inside of homes, and nobody ever sees. And that was hard. We were asking them to tell their stories over and over and over again in order to match the kind of publicity that was surrounding this long-standing—this moment of MeToo.

And so we said, Well we have to go and try to change this federal law, and we know we’re like hurting inside. Right? All these stories are hard to tell over and over again, and you’re getting a lot of incoming. So the last thing that we did was we brought everyone together in DC for three days, and we did a day and a half on building resilience and healing from trauma in order for them to feel like, I can tell my story and instead of that re-hurting me or taking away from my leadership, it actually builds my leadership because I’m doing it with other women in this room. And we practiced resilience and we practiced building this muscle of resilience together. And then we went on the Hill and we met with every senator and congressperson we could. And to the point where there will be over the next couple of years some expansion of that federal law.

So this is [APPLAUSE]—Their actions were made more powerful by their ability to say their stories out loud, and their resilience building enabled them to continue to tell their stories out loud, so that telling their stories out loud leads to more action. So that’s ultimately why we were like, You have to integrate these two; you can’t ignore either. [APPLAUSE]

We can take a couple of people. You want to line up? Ask questions or comments of me or domestic workers…

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Have you worked establishing any kind of group medical?

RAQUEL: So the Domestic Workers Alliance, one thing we focus on is not just the standards but also can we create our own products. So we’re launching, in a couple of weeks, something called Alia, in which your employers can each donate or like pay a dollar, or however much they want a month, to a fund that’s attached to a worker, and that worker can decide what to do with that money. So we’re pooling money for them, like making a pool of money for each individual worker, and they can decide if they want to get healthcare or if they want to take a day off and get it paid because they have the account. So we’re setting up accounts for every worker, and employers can pay into that. So that’s one way we’re trying to create benefits.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: What about getting rights for sex workers?

RAQUEL: You might have answered your own question. [LAUGHTER] I mean, I just think that is. Right? There actually is some organizations that are working on that. I mean, they’re already there, and that can be amplified.

STACI: COYOTE. Do you know COYOTE? Anyway, there’s a lot of sex worker organizing, where sex workers are doing their own organizing and setting the vision and standards there about value. So COYOTE’s one you could check out.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Women in agricultural positions have stopped reporting worker violence due to ICE. How to help people in those conditions?

RAQUEL: I mean, we just have to keep building power and organizing. There’s just no way around it. We’re actually going to move to Prentis as soon as I answer this question. I just want to make sure we have time.

But I will say that a lot of—When we engage—When we started working on sexual harassment and sexual abuse, we were really clear that this is one more exploitation on top of a bunch of others. Right? Like immigration, like low wages, like all of that. So we are not in the business of only fighting one at a time. We are in the business of fighting them all. And the only answer to that is that we have to keep building power and a different kind of power than the one’s that’s been placed on us.

STACI: Can you just—Just to help—Will you say what building power is? Will you just translate that real quick?

RAQUEL: Yeah. So…There’s—Alright. So there’s different kinds of power. [LAUGHTER] There’s economic power. Right? The power to own systems. So most people who have privilege in this country are able to possess wealth and set the market, set the prices, and get their own profit. So there’s economic power.

There’s political power – who’s in office, who sets the laws, how the system is set up to define who gets into office, all of that. Those are also the political power that sets up the criminal justice system or the labor system.

There is narrative power, which we actually have a lot of. Right? The ability to tell our stories to define a new future.

And then there is the ability to disrupt, disruptive power, to stop the systems as they’re functioning so that they can’t function as they do, as they have been.

So when we’re talking about building power, we’re saying, How can we amass the most amount of people to disrupt, to create our own narratives and our vision of a future, to create our own kind of systems that we want to set up, and also to shift the economy, the economic power, the market power, and the political power, the democracy? How do we shift the economy and the democracy so it works for the good of the whole as opposed to the few?

STACI: Wasn’t that well done? That was well done. [APPLAUSE]

PRENTIS: Hey y’all. So I’m going to talk a little bit about my work with Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity. I’m on the training team there, and I’ve been there for the last three years I’ve been a part of that training team. And what’s interesting about BOLD – and I’ll just kind of break down what we do in a little bit – is that all of us who are on the training team are also folks that are doing either working as somatic practitioners or also organizing in our own realms and capacities. So we’re a training team that is like bringing the information that we have and the learnings that we have right back into our fellow organizers so there’s not that kind of separation between us.

One thing I want to say, someone was talking about what is oppression, or that question came up, and I just wanted to clarify that systemic oppression—not clarify, but add—systemic oppression gets enforced in many ways through trauma. It gets enforced that way, so there’s not actually much—When Staci was talking about individual healing and collective healing and systems change, there’s a direct correlation because in many ways, how oppression gets enforced and how it lands on our bodies is through trauma. So the trauma of systems. Right? And that can look like a whole lot of things, but you can just imagine all the ways that these systems kind of land on families, bodies, communities.

I was talking earlier about the impact of prisons on communities, right, the impact of prisons on my own family, the impact of prisons on my own community. You can see how it is enforced by trauma. So there’s trauma that communities are dealing with present time, and then there’s trauma over time that becomes cumulative – however you say that word – and also just kind of gets embodied in our relationships when we haven’t had a chance to process or heal from the trauma on the scale at which we need to. And those…When that became clear to me, that’s part of what we’re up to, that’s when I became drawn to the project of BOLD and found it to be a really important space for me to kind of ask and interrogate those questions.

So black movement historically has been really criminalized, to say the least. Black movement in the US, maybe some of us are familiar, has been deeply criminalized. Folks involved have been punished in a lot of ways, including death, for organizing and engaging in black movement. And because of that, black movement in the US had been in a period – I’m not saying folks weren’t organizing, but there had been a period of fraction, been a period of a non-cohesion around how we were going to sort of make the change that we needed in our lives. And I think that had a lot to do with the trauma and the pain, and the oppression, and the repression that actually came down really hard on black movement.

So BOLD has been committed to for the last seven years – and a lot has happened in that seven years, hasn’t it? BOLD has been committed to rebuilding the infrastructure of black movement, which might sound like a pretty straightforward task, but there’s a lot of complexities in there. And one of the things that I appreciate about BOLD is that BOLD has been committed to doing that with somatics as one of the foundational elements of that.

So how do we actually feel what’s here? How do we actually build relationships? How do our organizations be in relationship so that the actual fabric of our movement is knitted back together? Right? Or even stronger than before? Right? There’s just much more possibility.

So it has been that meeting place. A lot of times I think about BOLD as being one of the heartbeats of black movement in this moment. We train hundreds of black organizers, movement leaders who come through the program. We have a directors and leads program, so obviously for organizational directors or folks in lead positions will come through the program and do—

There’s three pillars of our work no matter what program, and that’s political education – And I will say for all of the work that we do, none of it is like we’re just going to feed you information. It’s about agitating. It’s about interrogating what it is you’ve learned, and all of these domains. So our political education isn’t like, This is the political ideology of BOLD. It’s like, Hey, we all draw from black feminism, black Marxism. Right? Let’s get all of these ideologies in together and figure it out, wrestle together. Right? Have something show up and emerge from us being in deep relationship in deep honor of each other’s lineages. So it’s a meeting place. So we do political education.

We do transformative organizing. Right? Because a lot of folks are organizing and we can kind of forget why we’re doing it, and what it’s supposed to do. What? I’m an organizer. It’s like let’s really talk about what does organizing mean, and what are some of the lineages and traditions inside of organizing, and what works for what you’re up to, and then there’s embodied leadership piece. It’s like how do I feel myself. Self-determination, I think, starts on a cellular level. Right? Can I feel what’s here for me? Right? Can I self-determine? Can I show up for my own commitment, and can I do that for my people? Can we show up collectively? Can we be in relationship? So this embodied leadership piece is how we unlock, transform, bring our fullest creativity and potential as black organizers. So we do that for directors and leads. And then our AMANDLA program is new organizers get to come in and drop deep into all of that.

One story I wanted to share with all of you is that I just got through four weeks ago, maybe, teaching the PRAXIS program, and that’s where we really—it’s not just talking to each other, we’re going to hit the streets. So BOLD has been in relationship with Ohio Organizing Collaborative for about four years now, and they’ve been organizing statewide, black-led organization in Ohio. And this year they’ve been working on getting this initiative on the ballot for the elections coming up. It’s going to reduce non-violent drug offenses to misdemeanors, which means hell-a folks, thousands of folks are going to get out of prison, [APPLAUSE] $100 million is going to be saved, and these folks have generated a plan through community organizing for what they can do with that $100 million. It’s actually going to support their communities.

So we have one of the lead organizers is on the teaching team. We’ve trained probably six of their staff, and we just did a program where we actually were embedded in their organization. We went to one of their chapters in Akron. And we—During the day we do some political education, some embodied leadership with somatics practices, and then we’d go out into the street and do door-knocking in the community. So folks would know what the initiative was about so we’d get folks out to vote.

And I have to tell you what a difference it made to actually center together before—I was actually driving a van taking folks out door-knocking, and before we would go out in the street, we would center together, length with depth: What are we committed to? What’s our purpose? And we’d take that to each door, and we’d take that to each interaction. So the interactions got so—There was so much connectivity between people again. Right?

The first day we didn’t do centring practice just to witness what people did. And no shade, people are getting the numbers, right? But they were like, Okay, can you sign this; Okay, will you get out? Okay, thank you. When we introduced somatic practices, the level of connection, the level of commitment, folks feeling heard, seen, felt, was so significant. And we also noticed that our numbers went up. So we had a goal for like getting – I think it was like in our three days, we had to get…I don’t know. We had like—We met like 2,000 people. We got like 500 commits to voting. But it was just like the numbers skyrocketed with the capacity to really connect with each other.

So I just wanted to share. There’s so much I could share with you about BOLD, and I know time is… So maybe I’ll share a couple other things then.

I guess I will say that one of the gifts and challenges of this space is really how do we feel what’s there for black people. Like as black people, how do we actually feel the depth of what is and use that to kind of energize and propel our action? And I just want to say kind of connective to what Raquel was sharing about, sharing resilience, building resilience together, it’s so very—it’s been so very key for us to have a space. We go out to the country to train, most of the time, on acres of land. And we feel. And we feel things that are big, old, deep, hard. And we build so much resilience together. Right? We practice together. We have so much wide, joyous celebration together too. And I will say that the kinds of strategies that have come out of the organizers there because of what they’ve been able to experience, the kind of relationships that organizations have been able to have, when there’s pressures of like funding. Like there’s only so much money out here. Right? But people have a lot of big work to do. And those are hard. A lot of fractures can happen around there’s not enough resources. But the way that we’ve been able to weather that or help support each other in that because we’ve had that space together has been so incredible. And it’s been amazing to be a part of, just doing that rebuilding work. How do we get back into relationship with each other so that we can build power?

And to me, healing is one of the ways in which we build power. We heal, we unlock, and we act. We have things to do, we need to organize. And healing is—It’s a capacity builder. And I see that happen all the time in the BOLD space. So I just wanted to share that. [APPLAUSE]

RAQUEL: So a couple of questions for Prentis.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Talking about stereotyping the black population, but something happening to white population as well. Keeps hearing white supremacy. Major divide between masculine and the feminine white. The masculine are oppressing women. Rape with police, white women are being raped too. Masculine and feminine are holding together because both oppressed. Same with immigration. Is there an organization for white women being oppressed in ways you can’t imagine.

STACI: There’s so many things in there. What I want to say is really…Prentis said this, Raquel said this, we cannot transform to equity and a balanced relationship with the Earth unless we have an intersectional analysis. Right? White supremacy, male supremacy, Christian hegemony. Sorry to use big words. Economic exploitation. Those are all interdependent. They’re all interdependent. So when we look at liberation, we’re looking at liberation for all peoples, and we sit in different social locations. Right?

So as white people, whatever our gender is, we have to deeply take on racism. Yeah? Because second wave feminism. Everybody knows second wave feminism? Okay? Second wave feminism was forwarding primarily white women, and then left a whole bunch of allies and transformation out of the equation because it wasn’t intersectional.

What’s awesome is our era is intersectional, and our era can go as liberation for everyone, and we all have different roles based on our social location. Yeah? So I’m going to pause there.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: Talking about domestic abuse. What happens when trauma explodes all over your agenda?

PRENTIS: That’s one of the real-est questions I’ve ever heard in a while. [LAUGHTER] That was very real. I will just say briefly to that, and other folks can add, is that one is that this is great because we’re acknowledging that it’s there. And first we have to do that. Most of the time we’re building agendas and we’re having meetings, and we’re touching on things, and we’re pretending like it’s not there. And therefore, we’ve factored nothing in, we have no other programs, we have no resources, we have nothing, and it’s just like, Oh my God, this is overwhelming. Right?

So I think first it’s like acknowledging, yeah, we’re asking people to open up. Any space we’re asking people to be vulnerable, to think about—to have choice even, is going to kick it up. So how do we factor that in on the front end so that it’s not just our overwhelm that gets… Do you know what I’m saying? But there’s actually a space for people to do what it is they need to do.

Trauma is real and it’s out here, and it’s in every single meeting you have. Right? And most of the time the people who get to participate are the ones that just know how to stuff things down. So how do we shift it so that people get to show up increasingly more whole and more full? [APPLAUSE]

[Staci noting time]

STACI: One thing we want to say too, first of all, thank you. You all have been super engaged and fabulous, and this, I just really appreciate it. I do want to give a shout out to do the amazing social change work that is happening through the National Domestic Workers Alliance, through BOLD – Black Organizing for Leadership and Dignity, another one of Generative Somatics partners is the Racial Justice Action Center, another is the Asian Pacific Environmental Network. Right? We’re all partnering out there, but folks need support and resources. So as you’re looking at where to give your resources and your time, your time and your money, please check out Generative Somatics, BOLD, National Domestic Workers Alliance. And we’re all online, so you can find us. So thank you for your support. [APPLAUSE]