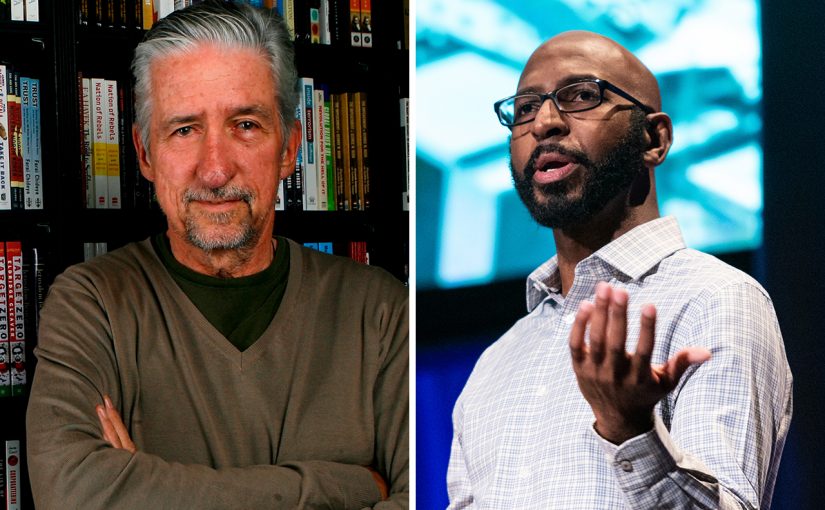

As climate chaos and obscene inequality ravage people and planet, a new generation of visionaries is emerging to demand a bold solution: a Green New Deal. Is it a remedy that can actually meet the magnitude and urgency of this turning point in the human enterprise? With lifelong activist and politician Tom Hayden, and Demond Drummer of Policy Link.

Featuring

- Tom Hayden (1939-2016) was one of the leading figures of the student, civil rights, anti-war and environmental movements of the 1960s, and went on to serve 18 years in the California legislature. Following his legislative career, he directed the Peace and Justice Resource Center.

- Demond Drummer is Managing Director for Equitable Economy at Policy Link, and a Fellow at New Consensus, a nonprofit working to develop and promote the Green New Deal that has advised many progressive leaders and organizations, including Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Sunrise Movement.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Kenny Ausubel

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Editorial and Production Assistance: Monica Lopez

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

Resources

The Green New Deal Bioneers Media Hub

Green New Deal Overview | New Consensus

The New Deal Wasn’t Intrinsically Racist by Adolph Reed Jr. | The New Republic

This is an episode of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature series. Visit the radio and podcast homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station and how to subscribe to the podcast.

This program was made possible in part by Guayakí Yerba Mate, working with Indigneous farmers in South America to grow shade grown, organic yerba mate. To inspire us all to come to life. Learn more about Guayakí’s products and regenerative mission at guayaki.com.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

NEIL HARVEY, HOST: As Yogi Berra once quipped, “The future ain’t what it used to be.”

The climate crisis is here now with a vengeance. It will be a long emergency that demands systemic solutions to prevent ecological ruin and the collapse of human civilization as we know it.

At the same time, extreme economic inequality has overshadowed even the infamous extremes of the runaway plutocracy of the Gilded Age.

The two crises are closely connected. Any real solution must address both.

The confounding factor is that there’s enough spin today to knock Earth off its axis. Several polls suggest that majorities of the public find it easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The challenge is that failing to imagine the end of capitalism may mean the end of the world.

Ever since the creation of the New Deal in the 1930s, powerful sectors of big business set out to dismantle its reforms, and subsequently the 1960s reforms of Lyndon Baines’ Johnson’s Great Society programs, such as the War on Poverty and Medicare.

By 2020, the corporate class had made great strides in rolling back and defunding those kinds of reforms – that is, until the Green New Deal began to emerge with real force and popularity.

As in the 1930s, the only force big enough to challenge this titanic corporate power is the federal government. That’s where the real money is, as well as the power to make the rules that govern society.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt summed it up in 1936 at Madison Square Garden: “We know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.”

But what really is the Green New Deal? And what exactly was the New Deal, and how did it come about?

TOM HAYDEN: I was born at a moment that the New Deal saved my family. It was before and during my birth and my first two or three years that this happened, so I can only go back and listen to people and ask what happened.

HOST: The late Tom Hayden first emerged on the national scene in 1962 as an author of the famed Port Huron Statement. It became the rallying cry of a generation, stating “If we seek the unattainable, it is to avoid the unimaginable.”

He went on to become a lifelong activist, working from both outside and inside the system – from the civil rights, anti-war and student movements of the 1960s to decades serving as a California State Senator and political force.

Born just at the cusp of the emergent New Deal, Tom Hayden first heard the stories from his mother about the life-saving difference it made in his family’s lives. He spoke about it at a Bioneers conference.

TH: What happened is that my grandfather died in a cannery accident, the fault of the Carnation Milk Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He fell in a vat and was chopped up. He left my grandma with 11 kids. And this was during the Depression, and she survived during the Depression and took care of those kids, and…during that time she was sustained by a $5,000 check from the company with regret for the death of her husband. There was no pension, there was no Social Security, there were no rights of organized labor. Her world fell apart in the late ’20s, early ’30s, and I don’t remember all that much about her, but I remember her as being sort of the quintessential Nani, you know, the grandmother, and all these kids.

And what they were doing in the Depression was huddling up together like students do today, five to an apartment who don’t know each other, but living through a semester at NYU or wherever. And they were selling apples, and they were doing odd jobs together and pooling what little they made every day in order to buy food and pay the bills to get to the next day.

They’re survivors, and they know a lot. I learned that too after leaving the university and going to Mississippi and Georgia and Newark that poor people know a lot that middle class people do not know unless they come from that background.

But anyway, in the middle of this process of the collapse of capitalism, the collapse of what government we had, there were the stirrings of the New Deal. There were social movements, Communist-party led organizing drives in manufacturing plants. Got nowhere. People got fired, got clubbed down, beat up, shot. Farmers—I don’t remember if they picked up pitchforks—but they went to work against the banks and the grange.

And they started a period of turbulent working-class expression and middle-class expression at having been sold out by somebody. And it started with finding ways to make enough food to eat, and it ended up with doing everything possible to obstruct the business as usual of the times unless they were fed, unless their children were fed, unless they could go to school, unless there was somebody to say that there was hope on the horizon.

And I remember my mom went through this, you know, the orphan of a father she hardly knew. And when I was growing up at the end of the ’30s and the beginning of the Great War, I remember sitting on her lap a lot and she’d always talk to me about how she loved Roosevelt. And I didn’t know who Roosevelt was, I just thought, Roosevelt, that’s God. [LAUGHTER] My mother loves God and God is—Roosevelt is taking care of us. She would keep saying that, because by that time, after these revolutionary inciting of working people and average everyday people, they had achieved Social Security, and I can’t tell you what that would mean for my mother when she’s thinking about Grandpa.

They achieved bargaining rights for organized labor. Unheard of. Seemingly impossible. They achieved pensions and all the rest of it, and they had achieved what was known as the New Deal, but at the time it was being built, they did not call it the New Deal, they called it “the movement”. It didn’t have a name. They didn’t announce, “Now we are starting a movement for a New Deal.”

What happened was this strange mix of a revolutionary impulse on the one hand; a liberal impulse from do-gooders who wanted a better government, second; people in the center who were very frightened at the possibility of social disorder and were timid about raising their head; and then people on the right like my priest, Father Charles Coughlin, who was busy organizing an anti-Semitic response to the very same conditions. And working closely with Henry Ford on the idea of a new Nazi party based in my hometown of Royal Oak or Hamtramck.

HOST: As President Roosevelt said in the face of the rising American Fascism:

“The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than the democratic state itself. That in its essence is fascism: ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or any controlling private power.”

Again, Tom Hayden…

TH: The people on the far right thought Roosevelt was a Communist. Most people that I would identify with were organizers. They were selfless people who didn’t work for much money, didn’t think far ahead, to the careers that they would hold as future labor bureaucrats or Democratic Party administrators [LAUGHTER], they wanted to know if they’d have their heads crushed by a policeman’s baton, and they were willing to do that. There’s sort of a lost generation there in history.

And there was another group, they were known as the brain trust of the New Deal, and they were a very eclectic group of people who were brainy, intellectuals. They were probably in the most important American tradition that I’ve ever studied, and I consider myself part of, the American pragmatic tradition. And I know that pragmatism is now a dirty word, but if you look under it, it means listen first, see how far people are willing to go, and improvise a step forward, a program that will take you a little bit towards survival or a little bit towards a better life as rapidly as you can.

The New Deal brain trust invented all these amazing programs. One parallel today would be like if somebody said, “We need a renewables work administration. We need to put every person in this country and on this planet who’s out of a job or underemployed into a great employment project, publicly funded, privately funded, but it has to happen because there’s a great work to be done.” The great work is to save us from the Depression in those days. No one had that idea in 1929. They were gripped with that idea by 1937.

The whole idea of industrial workers being organized, of old age pensions, delivering people Social Security, having to sit at a table and argue about whether we can also do healthcare, being told by the president we don’t have the votes, we can’t do that, some future generation will fight for healthcare, that’s how the New Deal was pounded out. It was just an unlivable situation. And out of that pragmatic determination they decided the government has got to hire people, the government has got to protect people, the government is what saved my mother, and why she loved Franklin Roosevelt.

It was a close call, you know. We could have gone to the right. We could have gone into chaos. And the answer to what might have happened we’ll never know ’cause then came World War II, and everybody thought, “Problem solved.” Everybody’s working down the street in the empty plant. They’re building planes and tanks and trucks and jeeps and cars. The car industry was formed out of that experience.

My father went to work as an accountant for a car company. Detroit was booming. My mother loved Roosevelt for those reasons, not ideological.

And when we come to that point when people are unable to be trapped in ideology but are willing to do what works, that’s the time when I think we’ll have the equivalent of a New Deal for the climate catastrophe.

HOST: The fork in the road that Tom Hayden foresaw has arrived sooner than even the alarmists projected. Climate disruption is already driving humanity to its knees, and it’s just getting going.

As climate chaos and obscene inequality ravage people and planet, indeed, ideology is starting to give way to pragmatism.

A new generation of visionaries is emerging to ensure that the Green New Deal that Hayden called for is poised to become a reality.

DEMOND DRUMMER: We see the Green New Deal as a World War II scale mobilization of all the resources of our country, our industrial capacity, our ingenuity, our financial capital, everything, all of the resources of our country to transition to a clean and just energy economy. We believe that we need to set out bold solutions that meet the scale and scope of the problem, and not let our politics define the type of solutions that we can implement. [APPLAUSE]

HOST: Demond Drummer is Managing Director for Equitable Economy at Policy Link, and a Fellow at New Consensus, a leading-edge non-profit policy “think-and-do tank” working with diverse partners to develop and promote a Green New Deal.

DD: So what are we proposing? We propose that we upgrade every single building in this country to the highest levels of energy efficiency, air quality, water efficiency, and water quality; upgrade our country’s infrastructure to be more resilient; accelerate, massively accelerate the adoption of renewable energy; restore our natural ecosystems; research, develop, deploy technologies to decarbonize heavy industry; and position our country to be a leader in clean manufacturing. Why can’t we do that?

We must also transform our food system and invest directly in farmers to adopt regenerative and sustainable agricultural methods. [APPLAUSE] Let’s take the subsidies away from Conagra and Monsanto [APPLAUSE] and give that money directly to farmers whose rural areas are being literally gutted of all their wealth. So we have a lot of work to do. The money is there. Don’t let nobody fool you.

So we also want to invest in America’s productive capacity to produce the stuff that we need to have a clean economy – electric vehicles, not too many, right, electric vehicles; the energy efficiency parts and components, pipes; all the stuff that we need to see the economy and have a society that we want. We have to build and produce more things here. About 25% of emissions comes from trade alone. So the economic mobilization will renew our economy and give rise to sustainable businesses and industries, and create millions of good, quality, high-paying jobs.

And because of the sheer size and scale of this great effort, the Green New Deal will leave no worker and no community behind. So the greatest generation mobilized our country to beat fascism abroad.

It is our task and our day and our time to beat fascism right here at home, and mobilize our country to meet the imminent and existential threat of climate breakdown. [APPLAUSE] And this is what the Green New Deal is all about.

HOST: At a deeper level, what’s also in question is the very economic paradigm that’s driving the destruction.

When we return, more on the comprehensive vision of a Green New Deal that Demond Drummer and a broad coalition of allies are working toward.

This is “The Green New Deal: Launching the Great Transformation”. I’m Neil Harvey. You’re listening to the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature.

HOST: When Demond Drummer was Executive Director at New Consensus, he worked closely with Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey to draft the original 2018 resolution outlining potential elements of a Green New Deal.

Only 14 pages long, it rapidly gained nearly 200 Congressional co-sponsors. It was designed to be the beginning of a larger creative process, with the details to be determined along the way – American pragmatism for the 21st century.

DD: You have to follow the rabbits down all of the rabbit holes. There is no piecemeal way to do this. And we do live in a system that took many, many years to get here, and it’s going to take some time to get back. And so we have to have a systemic solution.

Climate breakdown is a consequence, a symptom of very flawed economic thinking, flawed economic theory, bad economic models that exclude and extract.

It’s impossible not to tackle all aspects of our society, and by tackle I mean really examine, interrogate, and change the policy regime and economic regime that we live in. And what role can a government play? They invented stuff in ways the government can improve the material lives of people in this country – regulating banks, labor standards, all of this stuff that did not exist prior. And all within, like, a few years.

And it wasn’t one bill. Everybody’s like it’s going to be one bill. No. It was like a series of executive orders and court rulings, everything, legislation, all of the above.

So we believe that the Green New Deal should be at least as comprehensive as that, everything from decarceration to decarbonization. We have just a few years to right the ship, and there is no way to do that without being bold and visionary and aggressive.

HOST: Drummer says there’s a precedent for what a fast-forward mass mobilization can look like – and how impossible it can look until you do it.

When the US entered World War II, the productive capacity of the country simply did not exist to wage war on that scale.

The financial capital came from the government as both purchaser of the end product and as lead investor. A country that could only produce 3,000 airplanes before the war had produced 300,000 by the war’s end.

In reality, says Drummer, examples abound where massive government resources act as the seed investor to develop new technologies, industries and products. 80% of the technology in the iPhone was directly developed through government-funded research. Not to mention numerous life-saving drugs and vaccines.

Big business had no problem with the government’s response to the Great Recession of 2008. The Fed printed money to buy out the banks’ bad mortgages, and the banks continued evicting millions of people from their houses.

DD: And we didn’t extract a demand. We didn’t say keep the families in the homes. We just bailed out the banks. So we got real creative when it came to bailing out Wall Street.

What we’re saying is we can be as creative, not just from a fiscal policy standpoint, but from a monetary policy standpoint, right, to bail people out of this climate crisis that we have created, that mostly has been created by corporations that we’ve allowed to control our society.

So money is a tool, administrative law is a tool. So we believe the federal government has a role. Right? By statute, the federal government can override any state. By statute, it’s Constitutional. Federal government should have a high standard that’s a floor. You cannot go below that floor. Any state can go higher. Done.

There’s nothing sacred here. We have to really interrogate how we got here, and be very clear that from systems of government to money, to law and policy, everything is on the table, because life itself is in the balance.

HOST: A non-negotiable goal that Green New Deal proponents have set is to ensure that equity is built into any legislation.

Many critics of the original New Deal characterize it as an intrinsically racist program, and even a failure as a model. They point to the fact that on average, black Americans received less in terms of benefits than white Americans, which is true. In order to get New Deal programs through Congress, FDR made a deal with the Southern Senators whose votes he had to have.

However, as the scholar Adolph Reed argues, focusing solely on racial disparities presents an incomplete picture.

There’s a reason, he says, that so many older black Americans speak fondly of the New Deal and enthusiastically supported the Roosevelt Administration.

For example, the Works Progress Administration employed 350,000 African Americans a year, about 15% of its total workforce. The same number were employed by the Civilian Conservation Corps, and there are other examples.

Critics often cite the design of the Social Security Act to deliberately leave out Black Americans, which is also accurate. Many targeted job sectors were excluded from the Act, and two thirds of African American workers were in those categories. Yet, Reed points out, out of the total 20 million workers excluded from social security, 75% were white.

In other words, it’s complicated. It’s about class as well as race, and how financial elites use racial divisions for their fiscal and political benefit.

In practice, universal policies such as a living wage and Medicare for All will make a transformative difference in the lives of Black Americans, other people of color, and white Americans as well.

As Tom Hayden projected, when ideology gives way to pragmatism – to doing what works – Demond Drummer’s comprehensive vision of a Green New Deal puts politics aside to implement the functional solutions that will address the crises facing us.

DD: The Green New Deal is a capacious framework that is designed to address the interlocking systems of oppression that affect us all. Some see this as a weakness, but I argue that the comprehensiveness of the Green New Deal is actually its true strength, because there is no way to truly transition to a zero-carbon economy without interrogating and challenging the logic of an economy that exploits people and extracts from the earth. [APPLAUSE]

And what we require in this moment is a new political consensus and a new economic consensus, a consensus that says that we will no longer be duped by the mythic invisible hand of the market–[APPLAUSE] a consensus that recognizes that the public sector has a fundamental role to play in shaping markets – energy markets, financial markets, labor markets – to serve the interests of society.

HOST: Coalition building is key to successfully crafting legislation that avoids perpetuating systemic inequalities. A diversity of voices is brimming with creative solutions on how to make that happen.

DD: So the Green New Deal is a movement of movements. It will be brought forth and sustained by an enduring alignment of our youth, who are leading the way and know that we all deserve clean air, clean water, and good food, workers who deserve pay on which a family can thrive. It’s being brought forth by scientists and researchers who can lead us into the light, and even by entrepreneurs of all types, investors even, who are looking for good returns that can renew this economy—they do exist—grassroots leaders and organizations who continue to lead change, mobilizations, moon shots, movements, that’s the story of our country. That’s the story of America. And we in this room and in communities all across the country are writing the next chapter of the American story. [CHEERS]

There is a direct correlation between wages that can’t sustain a family and an economy that can’t sustain human life on this planet. [APPLAUSE] So this morning, we, the people, we have an economic mandate. We have the ingenuity, we have the existential imperative, and the power to give ourselves a Green New Deal. And I know deep in my heart and in my soul that we can, and even more that we will. Thank you so much, Bioneers! [APPLAUSE]