They say love means never having to say you’re sorry. But what if that popular aphorism from the 1960’s is wrong and that love precisely means having to say you’re sorry? Can an apology release the trauma, grief, rage and disfigurement arising from past abuse? But what if the perpetrator does not apologize? Can you still resolve or reconcile the trauma and hurt? How?

These are some of the agonizing questions that the artist, playwright, performer and activist Eve Ensler, now known as V chose to face to resolve her own relationship with her abusive late father. She did it by writing a book, The Apology.

In writing it, she tried to imagine being her father. Who was he? What allowed him to do such terrible harms? Could she free herself from this prison of the past? Could she free both of them?

Featuring

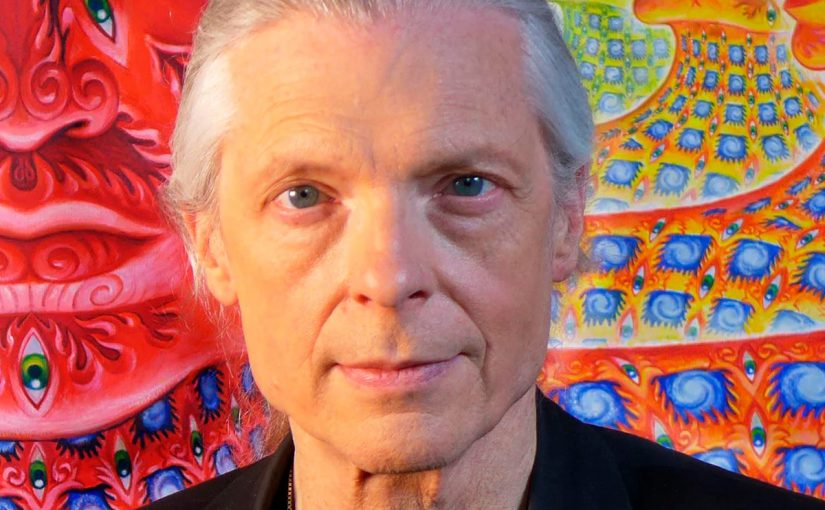

- V (formerly Eve Ensler), Tony Award-winning playwright, performer, and one of the world’s most important activists on behalf of women’s rights, is the author of many plays, including, most famously the extraordinarily influential and impactful The Vagina Monologues, which has been performed all over the globe in 50 or so languages.

Credits

- Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

- Written by: Kenny Ausubel

- Senior Producer and Station Relations: Stephanie Welch

- Host and Consulting Producer: Neil Harvey

- Producer: Teo Grossman

- Program Engineer and Music Supervisor: Emily Harris

Music

Our theme music is co-written by the Baka Forest People of Cameroon and Baka Beyond, from the album East to West. Find out more at globalmusicexchange.org.

Additional music was made available by:

- Ketsa at FreeMusicArchive.org

- Gigi Masin at MusicFromMemory.com

This is an episode of the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature series. Visit the radio and podcast homepage to find out how to hear the program on your local station and how to subscribe to the podcast.

Subscribe to the Bioneers: Revolution from The Heart of Nature podcast

Transcript

NEIL HARVEY, HOST: Love means never having to say you’re sorry.

But what if that popular aphorism from the 1960’s is exactly wrong? What if love precisely means having to say you’re sorry?

Can an apology release the trauma, grief, rage and disfigurement arising from past abuse?

Can an apology free both victim and perpetrator from the prison of unresolved past harms?

Can an apology lead to the forgiveness that allows for genuine transformation?

But what if the perpetrator does not apologize? Can you still resolve or reconcile the trauma and hurt? How?

And can an apology close one door and open another – unearthing yet deeper layers of pain and grief yet to be healed?

These are some of the agonizing questions that the artist, playwright, performer and activist Eve Ensler, now known as V chose to face to resolve her own relationship with her abusive late father. She did it by writing a book, The Apology.

In writing it, she tried to imagine being her father. Who was he? What allowed him to do such terrible harms? Could she free herself from this prison of the past? Could she free both of them?

This is “The Apology: Love Means Having to Say You’re Sorry”.

I’m Neil Harvey. I’ll be your host. Welcome to The Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature.

V: This is an offering, not a prescription. If it doesn’t work for you, release it. If it does, excellent. When I use the word woman, I mean to include women – straight, gay, bi, trans, non-binary, queer, gender queer, agender, and gender fluid. [APPLAUSE]

HOST: V has spent most of her adult life working tirelessly to end violence against women and girls. She founded V-Day and One Billion Rising, which have become global forces to prevent the 1 billion women and girls around the world from the physical and sexual violence that plagues this half of the world’s people.

For V, this struggle is profoundly personal. She directly experienced that violence beginning from her early childhood. She spoke at a Bioneers conference.

V: I was sexually abused by my father from the time I was 5 until I was 10. Then physically battered regularly and almost murdered several times until I left home at 18. Some place deep inside, I believe my father would one day wake up out of his narcissistic, belligerent blindness, see me, feel me, understand what he had done, and he would step into the deepest truest self and finally apologize. Guess what? This didn’t happen. And yet the yearning for that apology never went away. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve rushed to the mailbox, believing that finally today there will be a letter waiting, an amends, an explanation, a closure to explain and set me free.

It’s 31 years since my father died. For over 22 of those years, I have spent and been a part of a glorious movement to end violence against women, struggling day in and day out to put an end to the scourge. I’ve watched as women break the silence, share their stories, face attack, doubt, humiliation, open and sustained shelters, start hotlines. I’ve been part of a movement that is 70 years old, began by African American women fighting off their rape of slave owners and white supremacists. I have witnessed the recent powerful iteration of Me Too. I’ve seen a few men lose their jobs or standing, a few go to prison, a few faced public humiliation, but in all this time, I have never seen or heard any man make a thorough, sincere public apology for sexual or domestic abuse. [APPLAUSE] In 16,000 years of patriarchy – and I have done a lot of research – I’ve never read or seen a public apology for a man for sexual or domestic abuse.

It occurred to me there must be something central and critical about that apology. So I decided I wasn’t going to wait anymore, that I was going to climb into my father and let my father come into me, and I was going to write his apology, to say the words, to speak the truth I needed to hear. This was a profound, excruciating, and ultimately liberating experience. And I have to tell you, I learned something very profound about the wound.

I don’t imagine there’s anyone sitting here today that doesn’t have a wound that they carry, that has in some ways defined or guided or determined your life.

And what I learned writing this piece is that when we sit outside the wound, the radiation pours down on us, but when we go through the wound, it’s very, very painful, and it feels as if we might die, but as we keep going and going and going, we come to a point of ultimate freedom. I’ve learned about what a true apology is.

We teach our children how to pray. We teach them the humility of prayer, the devotion of prayer, the attention required, the constancy, but we don’t teach our children how to apologize, or maybe they get to say an occasional meager, “I’m sorry if I hurt you,” or “I’m sorry if you feel bad,” but what I learned writing this book is that an apology is a process, a sacred commitment, a wrestling down of demons, a confrontation with our most concealed and controlling shadow.

HOST: But what exactly is a true apology? What does it take to truly inhabit another person’s interior life – to know their wound?

V: I learned that an apology has four stages, and all of them must be honored. The first is a willingness to self-interrogate, to delve into the origins of your being, what made you a person who became capable of committing rape or harassment or violence, to investigate what happened in your childhood, in your family, in this toxic, toxic culture.

In my father’s case, he was the last child, the accident who became the miracle and he was adored. But I’m here to tell you, adoration is not love. Adoration is a projection of someone’s idealized self-image onto you, forcing you to live up to their image at the expense of your own humanity. My father, like many, many boys, was never allowed to be tender, vulnerable, full of wonder, doubt, curiosity and yearning. He was never allowed to cry. All of those feelings had to be stifled, pushed down, and in doing so they metastasized, and eventually became what he called the shadow man, this buried creature who later surfaced as a monster.

The second stage of an apology is a detailed accounting and admission of what you have actually done. Details are critical because liberation only comes through the details. Your accounting cannot be vague. “I hurt you,” or “I’m sorry,” or “I’m sorry if I sexually abused you” just doesn’t do it. Those words don’t mean anything. One must say what actually happened. “Then I grabbed you by your hair, and I beat your head over and over against the wall.” This investigation into details includes unmasking your real intentions and admitting them. “I belittled you because I was jealous of your power and your beauty, and I wanted you to be less.”

Survivors, and I know there are many here today, are often haunted for years by the why. Why would my father want to kill his own daughter? Why would my best friend drug and rape me? There is a difference between explanation and justification, and knowing the origin of a perpetrator’s behavior actually begins to create understanding, which ultimately leads to freedom.

HOST: V found that, although knowing the origin of a perpetrator’s behavior can create understanding that can lead to freedom, it doesn’t make the behavior any less repulsive. On the other hand, not facing it would keep her trapped in the cage of the victim-perpetrator paradigm that her father had designed.

V: One of the hardest things about writing this book was how deeply I didn’t want to feel my father’s pain. I didn’t believe he had earned the right from me to feel his pain. But to be honest with you, I have remained connected to my father since the time of the abuse through my rage. I was a permanent victim to his perpetrator. And I just want to say about my anger, I was very able to be compassionate to so many people in my life, in all sorts of countries and places, I always had compassion. But I found the way I talked about white men very dis-compassionate. I found it in anger, and I listened to myself. There was a part of me that I just wasn’t happy with. I was stuck in a paradigm I realized that my father had designed. And as my father’s mother says to him in my book, anger is a potion you mix for a friend but you drink yourself. Feeling my father’s pain and suffering, ironically, released me from his paradigm.

The third stage of an apology is opening your heart and being, and allowing yourself to feel what your victim felt as you were abusing her, allowing your heart to break, allowing yourself to feel the nightmare that got created inside her, and the betrayal and the horror, and then allowing yourself to see and feel and know the long-term impact of your violation. What happened in her life because of it, who did she become or not become because of your actions?

And the fourth stage, of course, is taking responsibility for your actions, making amends and reparations where necessary, all of this indicating you’ve undergone a deep and profound experience that has changed you and made it impossible for you to ever repeat your behavior.

What and why should one want to undergo such a grueling and emotional process? The answer is simple: freedom. No one who commits violence or suffering upon another, or the Earth, is free of that action. It contaminates one’s spirit and being, and without amends often creates more darkness, depression, self-hatred and violence. The apology frees the victim, but it also frees the perpetrator, allowing them deep reflection and ability to finally change their ways and their life.

My father, in my book, wrote to me from limbo, and it was very strange. I have to tell you, he was present throughout the entire writing of the book. He had been stuck in limbo for 31 years. I truly believe that the dead need to be in dialogue with us, that they are around us, and they are often stuck, and they need our help in getting free.

With this exercise, I believe now that my father is free. And because he was willing to undergo this process, he’s moved on to a far more enlightened realm.

As for those of you who cannot get an apology from your perpetrator, I believe that writing an apology letter to yourself from them is one of the most powerful things I’ve ever done, and it can shift how the perpetrator actually lives inside you, for once someone has violated you, entered you, oppressed you, demeaned you, they actually occupy you. We often know our perpetrators better than ourselves, particularly if they are family. We learn to read their footsteps and the sounds of their voices in order to protect ourselves. By writing my father’s apology, I changed how my father actually lived inside me. I moved him from a monster to an apologist, a terrifying entity to a broken little boy. In doing so, he lost power and agency over me. [APPLAUSE]

We cannot underestimate the power of the imagination. And I just have to say in these times that we are living in, our imagination is our greatest tool. It is shifting trauma and karma that has numbed our frozen life force, and in the deeper and more specific my imagining and conjuring in this book, the more liberation I experienced. When finally at the end of the book my father or me, or me or my father, or both of us as one – I’m so not clear who wrote this book – my father says to me, “Old man, be gone.” It was exactly like the end of Peter Pan. Do you remember when Tinkerbell says goodbye and goes [MAKES SHOOSH SOUND] into the ethers? My father was gone, and to be honest, he hasn’t come back.

HOST: From monster to apologist. From terrifying figure to broken little boy. Free at last – even when it meant writing the apology herself – to liberate them both.

When we return, V’s descent into the hidden depths of what saying you’re sorry really means took her somewhere she did not expect to go – to her mother – Mother Earth.

I’m Neil Harvey. You’re listening to the Bioneers: Revolution from the Heart of Nature.

As V freed herself from the psycho-spiritual cage of her father’s abuse, she began to wonder: What other apologies need to be made? Where else can the alchemy of apology create healing in this broken world?

V: I think often we are survivors of all kinds of things, whether it’s racial oppression, or physical oppression, or economic oppression, or sexual violence. We’re told that we have to forgive and get over it. I don’t really believe that the mandate is ever on the victim to forgive, ever. But I do believe that there is an alchemy that occurs with a true apology, where your rancor and your bitterness and your anger and your hate releases when someone truly, truly apologizes.

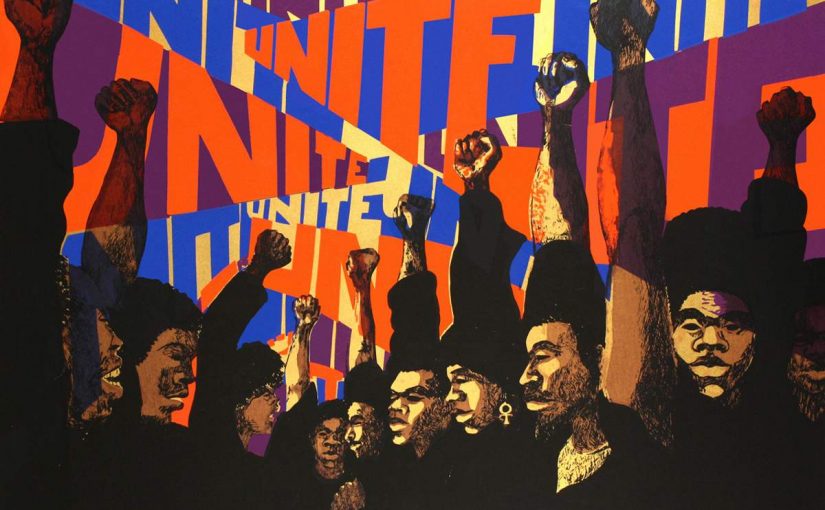

People have asked me throughout the tour of my book, “What will it take to get men to apologize?” This is the $25 million question. And I have to tell you, it’s a question that is underlying everything that we are experiencing on this planet right now. Our entire country rests on unreckoned landfill. That’s why it so easily becomes unraveled. Think of the massive apology and reparations due the First Nations people for the stealing of their lands, the rapes, the genocide, the destruction of culture and ways. [APPLAUSE]

Think of the apology and reparations due African Americans for 400 years of diabolical slavery, lynchings, rape, separations of family, Jim Crow and mass incarceration. [APPLAUSE] I honestly believe that apologies, deep, sacred apologies are the pathway to healing and inviting in the New World.

HOST: If deep sacred apologies are a pathway to healing and inviting in a new world, what about the world itself – the natural world that gives us life – that’s literally our home. V delivered this apology to Mother Earth at the Bioneers Conference.

V: So as I was preparing this talk, something miraculous and difficult happened. I realized there was an apology I needed to make, an apology that would force me to confront my deepest sorrow, my guilt and shame, an apology I had been avoiding since I moved out of the city to the woods where I now live with the oaks and the locusts and the weeping willows, Lydia, the snapping turtle, running spring water, foxes, deer, coyotes, bears, cardinals, and my precious dog Pablo. This is my offering to you this morning. It is my apology to the Earth herself.

Dear Mother, it began with the article about the birds, the 2.9 billion missing North American birds. The 2.9 billion birds that disappeared and no one noticed – the sparrows, the blackbirds, and the swallows who didn’t make it, who weren’t even born, who stopped flying or singing, making their most ingenious nests that didn’t perch or peck their gentle beaks into moist black earth. It began with the birds. Hadn’t we even commented in June, James and I, that they were hardly here? A kind of eerie quiet had descended. But later they came back, the swarms of barn swallows and the huge ravens landing on the gravel one by one.

I know it was after hearing about the birds that afternoon I crashed my bike, suddenly falling and falling, unable to prevent the catastrophe ahead, unable to find the brakes or make them work, unable to stop the falling. I fell and spun and realized I had already been falling, that we had been falling, all of us, and crows, and conifers, and ice caps, and expectations falling and falling, and I wanted to keep falling. I didn’t want to be here anymore, to witness everything falling and missing and bleaching and burning and drying, and disappearing and choking and never blooming. I wanted—I didn’t want to live without the birds or bees, or sparkling flies that light the summer nights. I didn’t want to live with hunger that turns us feral and desperation that gives us claws. I wanted to fall and fall into the deepest, darkest ground and be still finally, and buried there.

But Mother, you had other plans. The bike landed in grass and dirt, and bang, I was 10 years old, fallen in the road, my knees scraped and bloody, and I realized even then that earth was something foreign and cruel that could and would hurt me because everything I had ever known or loved that was grand and powerful and beautiful became foreign and cruel and eventually hurt me. Even then, I had already been exiled, or so I felt, forever cast out of the garden. I belonged with the broken, the contaminated, the dead. Maybe it was the sharp pain in my knee or elbow, or the dirt embedded in my new jacket, maybe it was the shock or the realization that death was preferable to the thick tar of grief coagulated in my chest, or maybe it was just the lonely rattling of the spokes of the bicycle wheel still spinning without me. Whatever it was, it broke, it broke inside me. I heard the howling.

Mother, I am the reason the birds are missing. I am the cause of salmon who cannot spawn, and the butterflies unable to take their journey home. I am the coral reef bleached death white and the sea boiling with methane poison. I am the millions running from lands that have dried, forests that are burning, or islands drowned in water. I didn’t see you, Mother. You were nothing to me. My trauma made arrogance, and ambition drove me to that cracking, pulsing city, chasing a dream, chasing the prize, the achievement that would finally prove I wasn’t bad or stupid or nothing or wrong.

My Mother, I had so much contempt for you. What did you have to offer that would give me status in the marketplace of ideas in achieving? What could your bare trees offer but the staggering aloneness of winter or a greenness I could not receive or bear. I reduced you to weather, an inconvenience, something that got in my way, dirty slush that ruined my overpriced city boots with salt. I refused your invitations, scorned your generosity, held suspicion for your love. I ignored all the ways we used and abused you. I pretended to believe the stories of the fathers who said you had to be tamed and controlled, that you were out to get us.

I press my bruised body down on your grassy belly, breathing me in and out, and I inhale your moisty scent. I have missed you, Mother. I have been away so long. I am sorry. I am so sorry. I know now that I am made of dirt and grit and stars and river, skin, bone, leaf, whiskers and claws. I am part of you, of this, nothing more or less. I am mycelium, petal, pistol, and stamen. I am branch, and hive, and trunk, and stone. I am what has been here and what is coming. I am energy and I am dust. I am wave and I am wonder. I am impulse and order. I am perfumed peonies and a single parasol tree in the African savannah. I am lavender, dandelion, daisy, dahlia cosmos, chrysanthemum, pansy, bleeding heart, and rose. I am all that has been named and unnamed, all that has been gathered, and all that has been left alone. I am all your missing creatures, all the sweet birds never born. I am daughter. I am caretaker. I am fierce defender. I am griever. I am bandit. I am baby. I am supplicant. I am here now, Mother, in your belly, on your uterus. I am yours. I am yours. I am yours. [APPLAUSE] Thank you.