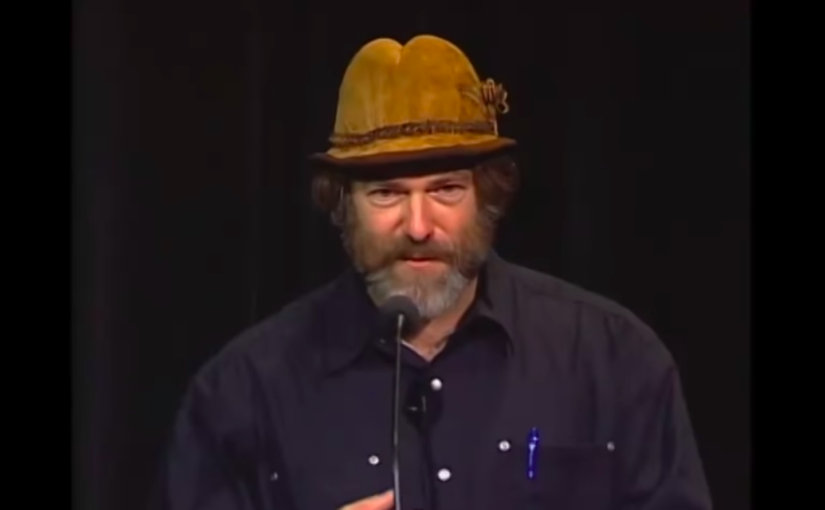

By Mark Shepard

Mark Shepard is the CEO of Forest Agriculture Enterprises who has developed a 106-acre polyculture farm by combining Permaculture, agroforestry and biomimicry principles. He is the author of Restoration Agriculture, a book that shares his experience on how to create an agricultural system that imitates the form and function of nature. Shepard gave this talk, transcribed and edited below, as part of the Bioneers Carbon Farming Series.

Twenty-five years ago, I decided to settle in southwestern Wisconsin and convert the land to a mimic of the natural plant community type that was originally there. I was 100% debt financed. I lived on the land and had nothing when I first arrived. About 60% of the land had been farmed in annual crops with only stubble left over from the previous year’s crop. The other 30% was incredibly over-grazed pasture where the grass was no taller than a golf course green with roots that didn’t penetrate the soil more than an inch. If it rained at all, you’d slip and the sod would tear, underneath was red-brick clay.

Using library references, I identified the biome and the dominant plant communities of that ecosystem that were in existence prior to the arrival of European settlers. Out of that list, I picked the species of the woody perennials that produce food, fuels, medicines, fibers, etc. Once I had chosen the perennial plants that I would use, I did a little bit of earthwork construction. The next step was to establish perennial polycultures using agroforestry techniques. The number one plant nutrient that we cannot do without is water, so everything is patterned after the water harvesting earthworks and the flow of rainfall on the land.

If you abandon a piece of land for millennia, it will naturally accumulate more top soil. Nature builds soil. The problem is how we do agriculture. If we mimic our natural plant community types, mimic the processes of our place, we’ll be able to build soil. A lot of people say it’s all about the soil life. Some people say it’s all about the soil minerals, or all about organic matter or compost. Actually, it’s about all of those combined. All of those work together to turn the solid planet Earth into bioavailable nutrients that plants can use in a cycle. All of it is important.

The decomposition cycle is key. We need to get stuff to rot because carbon is energy. It’s the fuel of the system. The more fuel you have on your site, the more the biological activity can burn that fuel to liberate more nutrients from the atmosphere, water and bedrock to the plants.

Trees that live the longest period of time in any place will chemically “color” the soil and transform it with their organic matter and also transform the biology that associates with them. Those trees will drive the soil chemistry. If a plant can’t tolerate the conditions that pine creates, it won’t live with pine. The same is true for walnut and other species.

Tree crops take time to mature, but we’re growing trees that are adapted to the area and we take a hands-off approach so we don’t have any expense in taking care of them – no inputs whatsoever. We’re going to continue to graze cattle and pigs, which are going to control weeds and provide fertilizer for our woody crops. Over time we’ll have additional crops coming off of the land.

If we’re going to take carbon out of the atmosphere, we need green to do that. The largest photosynthetic organisms are trees. They exude sugars into the soil. Sugars are carbohydrates – compounds made up of atmospheric carbon. Trees make leaf litter. They make bark flakes. They’re alive. Even if your grasses are dormant, trees can still photosynthesize. Even trees that have lost their leaves photosynthesize. Atmospheric gasses are exchanged through tiny holes in their stems called lenticels and the layer of green cambium just beneath the bark in young branches photosynthesizes, albeit a lot less than leaves.

We plant natural plant communities with a hands-off approach, and let them grow. If we don’t plant things to fill a particular niche in space, other things are going to come in and plant themselves that we may not necessarily want. Let’s occupy the site with the species that we do want and farm them.

On my farm in southwest Wisconsin, we selected the oak savannah as the plant community type. The plant community that has adapted with the oak savannah includes apples, hazelnut, the prunus species (cherries, plums, peaches, nectarines, almonds), raspberries, blackberries, grapes, currants, and gooseberries, which provide a variety of edible market crops as well as animal feed. We planted the trees first. As the trees are maturing, we grow hay, pasture, small grains, produce and cover in between the trees.

Our design consists of an alley, a swale, a berm and trees. That pattern is repeated so the water, instead of going downhill into the valley and flowing away, gets caught in the swale and spreads out to the ridge. This is done by just slightly changing the orientation of the fields.

In alleys where we raise row crops or produce, we lightly till the soil, maybe only two, three inches deep at the most, with a rotovator or a disc harrow depending on what crop we’re going to plant. We use yellow sweet clover, red clover, white clover and hairy vetch as a cover crop to take atmospheric nitrogen out of the air and put it in the soil where it becomes fertilizer for the next crop. In the area where we tilled there’s going to be a collapse of soil life, that’s where we plant cucumbers or squash or green peppers for wholesale markets. But not all of the soil is disturbed by tillage. The undisturbed area is the refuge for soil life that can come back out and colonize where we tilled and planted.

Yellow clover is also a source of nectar for honeybees. We get about a hundred pounds of honey per acre of yellow sweet clover. That’s an additional yield. Then it is it all goes to seed. What’s my biggest weed problem? Clover. That’s not really a problem. We’re not afraid of weeds in the crop. I didn’t want to spend an inordinate amount of time, or heaven forbid have to hire somebody, to pull weeds, I’m not going to do that. I’m just going to let the plants duke it out. I’ll take reduced yields, but by saving on labor costs, I’ll come out ahead.

After the crop is harvested, we lightly disk it up. Once again, just a shallow disking that incorporates all those different weeds back into the soil, keeping the fungal process, the decay process, going. Then we’ll broadcast a winter rye, winter wheat, or winter triticale, some sort of winter cover crop that’ll quickly turn green.

The rye, wheat or barley cover crop that we put down in the fall grows the next spring. If we need it for cash, we’ll hire a neighbor to come in with a combine and harvest it. If we want it for feeding and bedding, we’ll bale it in small dairy square bales. There’s grain and straw in it, and pigs and chickens like to nest in it.

In our wheat fields, we’ve got at least three different kinds of clover mix, plus all kinds of wild and crazy weeds. I’m not necessarily growing acorn squash, I’m growing carbon. Winter rye puts down about 6,000 pounds per acre of hard woody carbon below ground, about 5,000 pounds in the straw above ground, that’s 11,000 pounds. Yellow sweet clover will do about 4,000 or 5000 pounds total between the roots and the tops, so I’m getting anywhere between 17,000 and 20,000 pounds of hard, difficult-to-decompose organic matter under the ground. It feeds the fungal food web, and maybe it takes a little nitrogen away, but after that first year the decomposer populations are built up. It’s amazing how fast the decomposer organism population amps up.

One of the most destructive things on the land is a drop of water landing on the bare soil because it splashes into the soil, and it takes the particles with it and then it settles out. It gives you a clay layer on the surface, which seals the soil surface. Your soil can’t breathe anymore. So, by utilizing the cropping system described above, I’m putting 6 inches of straw mulch on a hundred acres of land. If you were to do this by hand or even by machine, it’s not very easy and a heck of a lot of work, but if you grow it in place and manage it, as I’ve described, you’ll get a kind of compost and mulch happening, with clover coming through it. The clover is helping to supply the nitrogen.

Once the clover starts to recover, I’ll move a little portable fence and I’ll bring in anywhere between a half dozen and 30 animals. I’ll buy small stocker cattle in the spring, graze them through the summer when I’ve got green grass. They can gain 300 pounds in 6 months. I pay $500 for a cow. It gains 300 pounds, if I buy it for a dollar a pound it’s now worth $800. I take it to the conventional sale barn. I’m buying cheap animals and I’m selling them on the cheap market where they’re going to go to a feedlot and get fattened. If it now weighs 800 pounds and I sell it for the same dollar a pound, I just turned $500 into $800. It’s a 60% return on my investment over six months. Why would I need barns and hay bales and all that kind of baloney? Just put the animals out there when the grass is green. They’re my labor force.

The key distinction is we’re using the livestock as the ecosystem management tool. Animals help manage the land. They recycle nutrients. They take carbon, chew it up, mix it with other materials, ferment it, and poop it out. They’re mowing the grass, they’re trampling. If I get a 50% trample and a 50% graze, I’m happy. Seventy-two cow patties per animal, and about thirty-five gallons of urine per animal per day. That’s a lot of fertilizer.

Then I bring in the mop-up crew after them, pigs. We put rings in their noses because I don’t want them plowing up the ground. On my farm, it’s all about the grass. We don’t want pigs rooting up all the grass, but they are perfectly good at picking up chestnuts that have bugs in them and have fallen off the tree, or apples from trees that abort fruit, or whatever is falling to the ground from your tree crops. Pigs can pick raspberries, they’ll pick currants, they pick grapes, and they eat a lot of grass.

We do not use deworming medications in our animals. As a result, we have good populations of dung beetles. They lay their eggs in the manure and bury it at the root zone of all of the plants. Dung beetles are an amazing creature and if we were using any sprays, we wouldn’t have those benefits. Cow patties just totally disappear, as does pig poop.

After a while, our tree crops start to yield. We’re getting yields in addition to what was going on underneath it with the animals and annual crops. Once you start generating branches, you have extra carbon. We cut and chip the branches. It’s fuel that feeds soil life, starting with fungi, which releases nutrients that feeds the crop, which in this case is grass for the cows.

What I do is first to go through an alley and remove any branches that are overhanging the alley, or the ones that want to scrape me off my tractor. I’m not pruning like a typical orchardist would. I cut the branches and then drop them to the ground in the alley. Next, I take Wine Cap Stropharia mushroom spawn and just scatter it. Throw it all over the place. Then I go through with my flail chopper and then I chip it up. Just grind it on the spot. The ramial wood chips are made from the small stems where most of the nutrients are stored in trees and woody plants. It is an amazing fertilizer that breaks down really fast, even in an arid environment.

You want to do it in the fall before the winter season comes on so you’ll get an optimal breakdown of the chips and the nutrients don’t just oxidize into the atmosphere. In chestnuts, I chop and drop just after blossom set so that nutrients will be released to fill and ripen a nut crop. In apples and pears, I chop and drop in late summer to mow the alleys before harvest and to give the hard-working trees a little shot of fresh nutrient before harvest.

Within three to six months, there’s hundreds of dollars worth of Stropharia mushrooms coming up. What does fungus do to wood? It helps to break it down and turns it into soil. That’s the way I turn wood into $300 and fertilizer. It’s a cool way to grow fertilizer.

With these practices, we’ve changed the land from a bare dirt desert with red clay subsoil into a nice rich black topsoil with the natural native plant community.