From racist mascots, to stereotypes in national creation myths like Thanksgiving, we have always faced misrepresentation and disrespect of our cultures and identities. Cultural appropriation and commodification of our cultures is commonplace, but Native activists, artists, youth, educators, legislators and our allies are changing that reality. We are winning battles to ban racist mascots and call out negative stereotypes in the media.

This episode features Crystal Echo Hawk, an enrolled member of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and President and CEO of IllumiNative and of Echo Hawk Consulting.

Crystal Echo Hawk (Pawnee), is the founder and Executive Director of IllumiNative, the first and only national Native-led organization focused on changing the narrative about Native peoples on a mass scale. Crystal built IllumiNative to activate a cohesive set of research-informed strategies that illuminate the voices, stories, contributions and assets of contemporary Native peoples to disrupt the invisibility and toxic stereotypes Native peoples face.

This is an episode of Indigeneity Conversations, a podcast series that features deep and engaging conversations with Native culture bearers, scholars, movement leaders, and non-Native allies on the most important issues and solutions in Indian Country. Bringing Indigenous voices to global conversations. Visit the Indigeneity Conversations homepage to learn more.

Credits

Executive Producer: Kenny Ausubel

Co-Hosts and Producers: Cara Romero and Alexis Bunten

Senior Producer: Stephanie Welch

Associate Producer and Program Engineer: Emily Harris

Consulting Producer: Teo Grossman

Studio Engineers: Brandon Pinard and Theo Badashi

Tech Support: Tyson Russell

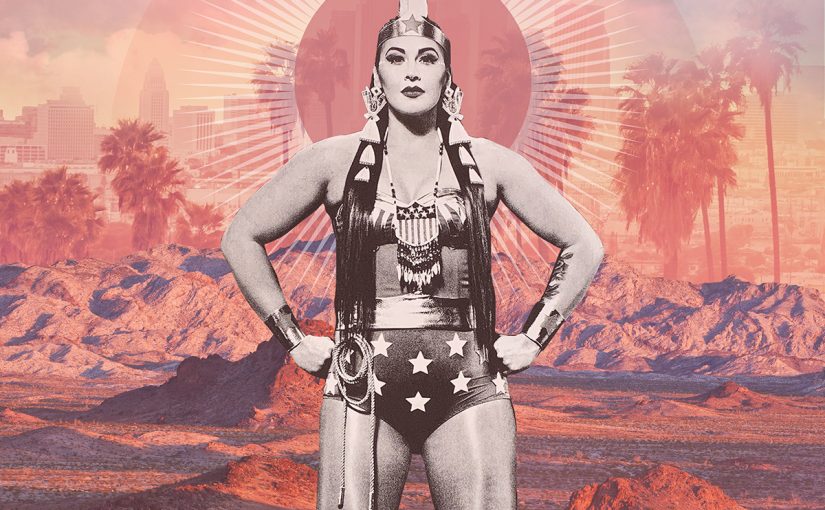

This episode’s artwork features photography by Cara Romero, Co-Director of the Bioneers Indigeneity Program as well as an award winning contemporary fine art photographer. Mer Young creates the series collage artwork.

Additional music provided by Nagamo.ca, connecting producers and content creators with Indigenous composers.

Transcript

CARA ROMERO: Hi Everyone, I’m Cara Romero and this is Indigeneity Conversations, a Native-led and curated podcast from Bioneers. I’m here with my dear friend and Co-Host.

ALEXIS BUNTEN: I’m Alexis Bunten and we have an amazing episode today that we’re really excited about.

We’re taking a look at an issue Native peoples have been working for decades to address through education, activism and social justice campaigns.

So, you probably heard recently that the baseball team, the Cleveland Indians finally changed their name to the Cleveland Guardians. This didn’t just suddenly happen overnight, of course. It happened after a really long and difficult fight by many, many people and organizations that have been driving home the point that racist stereotypes of Native peoples are really harmful, and they have very real and negative effects on our communities.

CR: And the Cleveland Pro sports team name is a really poignant example of many battles taking place across the US to get rid of Native mascots in schools and sports. Many of these of these fights are covered by the media, but they usually aren’t covered from the perspective of Native peoples.

And Mascots aren’t the only issue Native People contend with: We face ongoing racism in schools and media – misrepresentation, like stereotyping and negative perceptions about our lifestyles and our very existence. All of these misconceptions and hostile attitudes towards Native peoples lead to devastating impacts within our communities – like depression, anxiety and youth suicide. They’re all tied to these ideas of systemic racism towards Native peoples.

I had a conversation about all of these issues with Crystal Echo Hawk, the President and CEO of IllumiNative. If you haven’t heard of IllumiNative, you definitely need to check them out. They’ve been one of the key organizations working to create cross-cultural understanding of the importance of accurate and contemporary representation of Native Peoples, and how getting rid of racist stereotypes helps create positive change.

AB: Crystal is a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma, and she’s just been such a mover and leader in our Native communities for at least 20 years. She’s worked with the Native American Rights Fund and she also founded and developed the Notah Begay Foundation.

In your conversation, Cara, you talked with Crystal about the work of IllumiNative, and especially about a national public polling project she designed and co-led. The report that came out of this project is called “Reclaiming Native Truth”. And as a professional researcher, I can definitely say that this report offers solid data showing how non-Natives view us.

But most importantly, it shows that when we have control over our own representations, that we can and do shift the dominant narrative…

Crystal is such an inspiration to me, I know you agree with me, Cara. We’re both total fangirls of hers so let’s get into the interview.

CR: Crystal, thank you so much for being here. We’re all fan girls, and we all just appreciate not only you and your presence but everything you’ve done for your community and the greater indigenous community in North America, it’s really just something to be so proud of. And please know that everybody notices all the work that you’ve done over the years very selflessly.

CRYSTAL ECHO HAWK: Well, at first I want to say the fan-girling is mutual. When I got the call, it was like, yes, sign me up. You know, just, again, just have so much admiration. You know, we’re all doing it. We’re all working hard to do these things for our people, but…

The Reclaiming Native Truth project was a project I founded and co-led back in 2016 to 2018. It was a two-year $3.3 million project, and it was the largest public opinion research project ever done about perceptions of Native Peoples.

And really what we did with a multi-faceted research team was really unpack what are the dominant perceptions and narratives that Americans from across the country hold about us, including those in the highest kind of ranks of power. We interviewed federal judges and law clerks, to members of Congress, and people in media, philanthropy, and even our allies in social justice to really begin to unpack what do the American public think about us, why do they think that about us, where do these core stories and narratives emanate from, and most importantly, how do they affect our people. And so Reclaiming Native Truth mapped all of that, and really was able to not only map what those perceptions are, the role of invisibility and toxic stereotypes, in really advancing racism, but on the flip side it actually showed us a pathway forward about how we really change the narrative or change the story in this country about Native people so that we can really change our future.

CR: I think that that invisibility is really important to emphasize. I mean, I think that it goes back definitely to public education and all of these experiences that we have. They were still making drums out of oatmeal boxes, and having all of the kids put on turkey feathers. And like the way that a child internalizes the—it’s humiliating.

And I love the work that Illuminatives is doing to counter that narrative. I mean, it’s work that so many of us are doing, but you guys are so front and center of countering those humiliating narratives that we’ve endured our entire lifetime.

CEH: We’ve all carried these senses of this kind of duality I think we all walk with as Native Peoples, is that we feel very much unseen and unheard in society. We feel very invisible, but at the same time if we are, then we’re just these caricatures, right? We’re the stereotypes, we’re some other sort of representation that is not of our own making. I remember as a little girl, I would run home after school and turn on cartoons, and I’ll never forget about this cartoon I saw. I think it was like Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd, and it’s like a Wild West sort of episode, and all of a sudden this very kind of stereotypical Indian man with a big red nose, kind of lumbering across the screen, but he was wearing a banner that said “Vanishing American”. And he walked across the screen and he disappeared; he faded to black.

And I just remember being in third grade, and just internalizing that, and never forgot that feeling. And I think from that to really I think what caused me to kind of really found Reclaiming Native Truth was just watching my daughter, like as a mother, watching my daughter be bullied because we had given her a traditional Dakota name, and watching her relentlessly being bullied that led to her almost taking her life, and really having a lot of struggles. And I think it was that, it was like enough is enough. And it was understanding that so many of us as mothers and fathers and aunties, and we all feel this in our professional lives, in our personal lives, about the impacts of our lack of representation and our misrepresentation have on our people and our children, and that’s really what was the catalyst to everything that I’m doing right now.

CR: I have just a similar way of stepping into the work, and probably a not uncommon story of being raised both on the reservation and in an urban setting. And I think when I first stepped out of the reservation setting, there was definitely a culture shock. I think that we have an understanding, a very private way of knowing and relating to each other within our communities, and when we step outside of our communities, it’s really shocking how people perceive us, and how very little they know about what it is to be a contemporary North American indigenous person.

And I internalized so many of those things as well, Crystal. And I went through school often exhausted of trying to explain the truth about, you know, where I’m from, which is a lesser-known tribe in California, about how we all look different, about how all of our traditions are different. And it is I think first and foremost exhausting.

And then I went on to university where I was a liberal arts major in Houston, and was studying anthropology, and everything that I experienced up to that point. And then in the university setting was taught as bygone, you know, that we were relics of the past.

And I realized instantly that through photography, and through media, I think specifically, even as a young woman, that a picture was worth a thousand words, and that maybe, just maybe I could use this to become a photo documentarian of modern Native Peoples, to use this skill to really communicate to people all the intricacies of our cultures, of how alive and how beautiful we are.

Crystal, I think the mascot issue really stands out for me as something that is changing in my lifetime. I have so much respect for everybody that’s been fighting this issue for decades. For me, it was really stepping into tribal college at the Institute of American Indian Arts, where one of the other Native students was wearing an Atlanta Braves hat, and I remember it very clearly, because, Char Teters called him out in class, and she was one of the early activists that was fighting for, you know, Change the Name. It was a little bit of a scene, but she was explaining to him all the things that we were just talking about, how we really internalized this oppression.

CEH: You know, this is a movement that’s been going on for decades and decades, and particularly with, you know, the Washington football team, I mean, really led by elders like Suzan Shown Harjo, Amanda Blackhorse, and just thousands and thousands of other Native Peoples who have just been organizing.

One of the biggest targets of all has been the Washington NFL team, you know, that was formerly known as the R word. Right? The R word is the N word. It’s a dictionary defined racial slur. But there is, you know, really racist Native sports mascots that show up in all professional sports – in major league baseball, hockey as well. But they’re prolific through K-12 schools as well…

Right? And it’s not just the logos and the imagery, or the dictionary defined slur that was the Washington NFL team, but it’s the fan behavior. Who, you know, with chants from rival teams and sports fans, things like kill the Indians. Right? You look at all this whole fan behavior and culture that gets associated with racist sports mascots. And what we found with our research is that that promotes discrimination and bias against our people. It’s the red face. And red face is black face.

And thankfully this country has moved to a point where it understands that black face is wrong. Right? We’ve watched people lose their jobs. But yet somehow red face is okay. The way that the mascot debate has been framed in this country is about it’s a matter of public opinion. Oh, well, you know what, this Washington Post poll that was done was sort of, you know, 500 self-identified Native people says it’s all okay. Or, hey, we found, you know, a Native person to come to the football game, you know, and it all looks good. It’s a matter of opinion. And it’s not—that’s the wrong question, the wrong framing. It’s about harm.

And when they did studies with Native children, they found—and with Native young adults, they found that it increases suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety. Right? The exposure to not only that imagery but everything around it. Right? So this is science speaking. This isn’t just a question of political science. This is actually showing that this causes harm to our children, and that they found that for Native young adults, they struggle to even see a future for themselves. It sort of depressed their ability to see the future.

And so when we look at our high skyrocketing rates of suicide, right, we look at the high rates of depression and the things that our people are struggling with, particularly our children, this becomes a matter of protecting our children from harm. This is what science is telling us.

And what we’ve found through our research is that promotes bias and discrimination against our people. Right? It is scientists and the studies, and research led by Dr. Stephanie Fryberg and other really amazing Native scholars and non-Native scholars have found that that level of representation fuels bias, it does fuel racism, and it’s important that we smash those toxic stereotypes.

So many of the things that came up in Reclaiming Native Truth about how, you know, just that the problems with stereotypes and the power of invisibility, I think on one level we all knew that and we’ve been talking about that and advocating it, and living it in our lives for so long. But to actually have data and evidence, right, to really show, as Dr. Stephanie Fryberg found from all of this research about the profound nature of our invisibility, right, which is really we found is institutionalized and perpetuated in big systems in this country, big systems like pop—you know, like popular culture.

And we think about everything that that entails, from sports mascots, to TV, to film, all kinds of things, museums, to looking at the role of media and really looking at the role of K-12 education. These are perpetuating our erasure and our invisibility, and that is – as Dr. Fryberg says – that invisibility is the modern form of racism against Native Americans today.

Part of our work at IllumiNative has not only been about the advocacy with the sports teams and schools and the media, but I think it’s also educating our own people about the harm that these representations have, and that this isn’t just a conversation that should be minimized and cast aside about public opinion or political correctness. So that’s really been kind of the work that we’ve been doing, and getting creative by partnering with artists and influencers, and finding ways in the media to kind of help create a social groundswell that people understand how important this issue is.

CR: I have so much respect for everybody that’s been fighting this issue for decades. And I think that what we’re seeing evolve with all of the contemporary media work is really this better future, right, where we’re able to choose accurate representations of ourselves. And that’s so powerful.

CEH: Yeah. Absolutely. Well, you know, the thing that we learned from the Reclaiming Native Truth project is that there’s such immense power in data, right?

You know, a big part of our work has been taking that research to Hollywood, for example, and meeting with the heads of the biggest studios out there, right, and educating their leadership about the importance of representation and not just check a diversity equity inclusion box. But that they’re no longer advancing harm by our erasure or by our misrepresentation. And that we were also able to show them through our research that 78 percent of Americans want to know more about Native Peoples. And what that 78 percent figure represents is audience demand. And that has really began to speak volumes to people within the entertainment industry, also in media and newsrooms, now that they understand there’s more of an audience there for our stories and our issues and what we think.

We have gone out and I’ve lost track now—it feels like hundreds of presentations I’ve done over the last two years and with my colleagues, traveling all over the country. And what we found is that when we go out and we educate our allies, I would say probably 85 percent of the people I talk to are like, “I didn’t know.” Once you walk them through how these big systems work and how they interact within these systems, and inadvertently sometimes, even through the best of intentions, kind of advance harmful representation about us, most people are like, “I didn’t know,” and “How do I change this?”

And so I think it’s really been the power of education and them understanding that they not only need to kind of wake up and understand and own that, but their guilt [LAUGHS] around that’s not helpful to us. What’s helpful for them is to really partner with us, and to really create platforms, and turn over the mic, so to speak, right, to Native Peoples. We don’t need non-Native Peoples to come in and save us. We need them, though, to be a partner in dismantling these systems that not only harm Native people, but they harm all of us and to really kind of go within the institutions and systems that they’re operating in, and saying, Wait a minute; how are we culpable here? How does Native representation show up and not show up? And that means everything from governance structures on boards of directors to staff in leadership, their hiring, to how they’re talking to Native Peoples, which nine times out of ten they aren’t talking about us. Right? So how do they need to make sure that we are in the room? So allies have an important role in all of this from a number of different angles.

CR: Crystal, what do you feel like has changed during your lifetime?

CEH: You know, I think about these sort of high points from, you know, over the last couple of years of just having our first Native US poet laureate, with Joy Harjo being named. Or with Wes Studi being the first Native American male actor to receive an Oscar, to things like the McGirt decision. The Supreme Court ruling that affirmed, you know, the Muscogee Creek Nation’s treaty rights, and its reservation, and that’s where I’m talking to you today, is sitting in the heart of the Muscogee Creek Nation, also known as downtown Tulsa, you know, and seeing, you know, big court victories for NO DAPL. Or looking at the exposure that was generated at the stand taken at Mt. Rushmore this summer. Right? And the way the LandBack movement has really kind of emerged from that. So it was amazing if we were watching that weekend of Fourth of July, it was like if you were watching MSNBC it was beautiful. There were nothing but a sea of Native faces speaking out on critical issues from mascots, to our treaty rights. I think it’s been exciting to kind of see, you know, how much of that is changing. And one of the biggest things is that in 2018 we elected the first two Native American women to Congress.

It’s just really about how we are building power. And so, our representation as contemporary Native Peoples and the way it’s showing up in all different facets is huge, and just those two women being elected, it’s really been transformative, and it really shows how important that aspect of our representation is as well. But, you know, it’s fairly recent. Right? We’ve been battling invisibility and misrepresentation pretty fiercely, and we still are, but to see the pace of change is really extraordinary.

CR: I think for me one of the biggest things that, again, I’ve seen change in my lifetime is when we talk about misrepresentation of Natives, it’s really hard to not talk about the Edward Curtis photographs. And the Edward Curtis photographs are an incredible body of work that were produced around the turn of the century by a non-Native photographer that’s aim was an ethnographic study to document the vanishing race. They were so beautiful, they captured America’s imagination, and really people’s imagination around the world.

But then it really kind of became this stereotype that stagnated people’s view of what Native Americans are – not only what they are, but what they should be. And I just remember feeling a lot growing up that, if you weren’t that, then what are you. You know?

And I really hone in on this messaging in my own art, because I feel like it’s really dangerous to tell a young Native person that you’re only good if you are the way that you were 100 years ago, right? When you completely gloss over, you know, all of the assimilation, all of the residential boarding schools, all the things that have brought us to this place, including all the resilience of the things that have survived that have brought us to this place. I think everything that exists is really kind of against all odds. You know?

So we have this incredible thing to celebrate. But I think it’s really important for everybody to take a look at what they think they know Native art is, or what they think Native Americans look like, because again, those stories that artists and educators and activists are telling on their own are really the ones that people need to be looking at for representation. I think it’s unique to IllumiNatives and to this work that you’ve done, that you incorporate the importance of art and Native artists into your work. Could you talk to us a little bit about the importance of Native art?

CEH: Absolutely. What was so beautiful as we began to really understand through the research the power of our representation, the power of an image. The majority of them haven’t been authored by us, right, and don’t reflect who we are today in the 21st century. and so I think, I’ve always throughout my career, you know, working with artists has been such an important part of the work that I’ve done, whether it’s around the Native American Rights Fund, right, and the work we were doing, to really around youth leadership development, but really with Reclaiming Native Truth, it really centered the importance of artists.

And in fact, you know, IllumiNative was co-founded by a circle of artists, and it was really their idea. I remember we sat in the room, we presented all of the Reclaiming Native Truth research to them. I think it was like February or January of ’18, 2018, and they said, You know what, we need an organization that can really not only take all this research and put it into action, but to really bring the power of artists and activists and organizers and our best thought leaders, because these systems are so big, and we need to join forces, right, if we’re going to change the narrative and change the story and the way that people see us and perceive us, then we really—we needed to really look at the role of culture and art to be the way. Because words and advocacy, sometimes it’s not enough to cut through the noise, and so it’s really understanding the power of art and culture as a leading force for really eventually policy and systems change. And so I really credit, you know, those artists with the call to action. They said, “Crystal, go build it.” [LAUGHS]

And, you know, we founded IllumiNative in June 2018 and haven’t looked back since. So I’m just really grateful for the—just the vision and leadership of all of our artists, and all the different genres and mediums that they work in, because it’s so powerful. They allow us, you know, to really see ourselves and envision ourselves in ways that sometimes society tries to bar—create barriers to us not being able to see a future for ourselves, or to see ourselves reflected as we are.

CR: Stories by us for us, you know? It really has this ripple-out effect of authenticity, of actual conversations, of ways of knowing how we interact with each other, that really almost always counters the narrative that’s out there, in my experience. I mean, we’re really focused. Um When we’re telling our own stories. We’re really focused on things that are very different than when non-Natives focus on our communities.

CEH: It’s really about the values, about caring for Mother Earth, for our environment, for caring for our communities and our elders, and thinking about the power of art and its different expressions from beautiful photography like someone like Cara, you know, whose images can move us, to beautiful murals that can inspire that radical imagination that can help us get out of this moment where we feel so out of control, or the world feels out of control, and when we can kind of cut through the noise and see a beacon of light.

And I think that that’s what artists can do in this moment is appeal to us in different ways. And I think now more than ever there’s an urgency around supporting that art and those perspectives, and that level of storytelling.

CR: I think one of the biggest changes in the last decade also is our connection to each other through the Web, through the Internet. You know, we come from isolated communities, you know. That was by design. And, you know, the Internet provided, you know, YouTube and social media, and I just really started consuming this connection to, you know, other Indigenous Peoples around the world, really. We are consuming YouTube videos that are homemade, comedy, dance, you know, bird singing in Southern California,. We are so connected on social media, on Instagram, you know, artist to artist, Native to Native, culture bearers to culture bearers. So I think that like us harnessing the power of social media is also something that IllumiNatives is focusing on, as well as so many artists in, you know, continuing to connect to each other through the Internet. That for me has been such a huge change in my lifetime for the positive.

And, I love the power of art and seeing Native artists rise to tell our own stories. And it is happening in Hollywood. It’s happening in 2D art. It’s happening with graphic design.

And you’ve really been at the forefront of that, Crystal, in making sure that you incorporate some powerhouse artists in your messaging, and it really comes across. Where I think as a Native person I can instantly look at IllumiNatives and know that that’s a Native-led organization. And that’s important. That’s important when you’re building trust in indigenous communities, is that we know who we’re speaking to.

CEH: You know, I always laugh, I go back and think about something that filmmaker Sterlin Harjo once said. Because somebody asked him like: What’s the ideal representation, like, in a TV show? And he said, It’s a Native man drinking a cup of coffee wearing a pair of jeans. And it’s like [LAUGHS]— and that’s it. And it was like it’s funny ha-ha, but it’s just to be normalized, right? For us to show up and not as the magical, mystical Indian, or, you know, we all know what it’s like when a Native person shows up on something, and we all like freak out, like it’s a rare—it’s like seeing a unicorn. Right? Or Sasquatch, right? [LAUGHS] Like when we see ourselves, we get so excited.

Simultaneously, there’s two Native TV shows. One by Sierra Ornelas, she’s a showrunner and created it with Mike Schur. It’s called Rutherford Falls, and it’s 50 percent of the writers room are Native Peoples. You have a Native woman as the co-star with Ed Helms. It’s breaking all the record books on Native representation. To Sterlin Harjo, who’s teamed up with Taika Waititi to develop the show Reservation Dogs that’s on FX. And, again, I mean, these are really significant but, you know, it’s fairly recent.

So I think the future is really about that, our representation, we are everywhere. And so I think it’s about that political representation, that we really hit parity in every single state and city, and nationally.

Or when we click on Netflix, or whatever we like to watch, that there’s ample choices around Native representation, and stories that are authored by us. You know, all kinds of stories, and not just the epic Westerns or the tragic tales, you know, about Native Peoples, but, you know, comedies and, you know, Natives in outer space! [LAUGHS] That we have the diversity of representation that not only reflects our humanity and the complexity of who we are but all of our contributions. Even imagining ourselves in the future. And that it just is on every level of society.

I really got choked up earlier, you know, when you were talking, Cara, about—as a young person through school, like how exhausting that was, our children have to constantly live in hostile learning environments, and it’s not only related to sports mascots, but that, because there’s nothing in the history books really about us that Native children today are still asked to get up and teach their classes – Native American history.

My dream is that that no longer is the case. That our children can go to school and feel positive about that experience, and that our history and our contemporary contributions to this country are reflected, and that we’re thriving.

There is such a power to the power of our story, and our stories. It really has the ability to change the future. I feel like in changing that representation, that we start to see that these big systems are transformed, that we are really about building Native power; we are about advancing justice and equity for our people. That is really my dream, and I really believe that it’s something that we’re going to achieve.

CR: Simultaneously, the dream is that all of those things are reversed, that we are creating and fostering future leaders, that we are fostering, you know, representation that’s empowering and uplifting, and that we’re able to reverse some of those negative correlations for ourselves and for future generations. That would be the dream.

Crystal, I can’t thank you enough for being here with us today. It’s always an incredible honor to share space and time with you, and thank you for joining us. And I just appreciate the work that you do so much, and please know that everybody sees you and your team over there at IllumiNative.

CEH: Well, it takes a village. It’s a big beautiful team of all kinds of people and I think this is also just an extraordinary time for Native women, right? In particular. And I just thank you for the work that you do, and just for creating this space and inviting me into your circle, and to connect with the amazing work that you do through Bioneers. So thank you.

CR: Thank you for joining us for this episode of Indigeneity Conversations. To learn more about the guests we featured today, go to the episode page on our website, bioneers.org/indigeneityconversations. You’ll also find more episodes there to listen to and share, and ways to become involved as an ally to indigenous peoples.

AB: And To find out more about our Native-led Indigeneity Program, go to our website bioneers.org/indigeneity. We offer more original Indigenous media content there along with our Indigeneity Curricula and learning materials for students and life-long learners.

CR: It’s been such a pleasure to share with all of you today. Many thanks and take care!